The Country Team and Local Staff Role | Excerpt from Inside a U.S. Embassy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Diplomacy Project: a US Diplomatic Service for the 21St

AMERICAN DIPLOMACY PROJECT A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Ambassador Nicholas Burns Ambassador Marc Grossman Ambassador Marcie Ries REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 American Diplomacy Project: A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design and layout by Auge+Gray+Drake Collective Works Copyright 2020, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America FULL PROJECT NAME American Diplomacy Project A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Ambassador Nicholas Burns Ambassador Marc Grossman Ambassador Marcie Ries REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs | Harvard Kennedy School i ii American Diplomacy Project: A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................3 10 Actions to Reimagine American Diplomacy and Reinvent the Foreign Service ........................................................5 Action 1 Redefine the Mission and Mandate of the U.S. Foreign Service ...................................................10 Action 2 Revise the Foreign Service Act ................................. 16 Action 3 Change the Culture .................................................. -

Legal Regime of Persona Non Grata and the Namru-2 Case

Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.32, 2014 Legal Regime of Persona Non Grata and the Namru-2 Case Marcel Hendrapati* Law Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Jalan Perintis Kemerdekaan, Kampus Unhas Tamalanrea KM.10, Makassar-90245, Republic of Indonesia * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Just like the diplomatic immunity principle, the principle of persona non grata aims to ensure justice for both the state seeking to evict a diplomat (receiving state) and the state whose diplomat is being evicted (sending state). This is because both principles can guarantee the dignity and equality of sovereign states when resolving issues in international relation. Not every statement of persona non grata has to culminate in expulsion because a statement may be issued by the receiving state both after the diplomatic agent has started performing his functions and even before he arrives at the receiving state. If such a statement is followed by the expulsion of the diplomat, it should be based on article 41 of the Vienna Convention, 1961 (infringement on laws of receiving state and/or espionage actions). Also, expulsion may occur due to war and severance of diplomatic relation between two states. Indonesia has had to deal with issues of persona non grata on several occasions both as receiving and sending state. This paper analyses several cases of declaration of persona non grata involving several countries, especially Indonesia in order to give a better understanding of how the declaration of persona non grata plays out between states, and the significance of the Vienna Convention of 1961 on diplomatic relations. -

The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 9 1988 The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Platt, F. Jeffrey (1988) "The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service by F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University The critical early years of Elizabeth's reign witnessed a watershed in European history. The 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, which ended the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict, resulted in a sudden shift in the focus of international politics from Italy to the uncomfortable proximity of the Low Countries. The arrival there, 30 miles from England's coast, in 1567, of thousands of seasoned Spanish troops presented a military and commer cial threat the English queen could not ignore. Moreover, French control of Calais and their growing interest in supplanting the Spanish presence in the Netherlands represented an even greater menace to England's security. Combined with these ominous developments, the Queen's excommunica tion in May 1570 further strengthened the growing anti-English and anti Protestant sentiment of Counter-Reformation Europe. These circumstances, plus the significantly greater resources of France and Spain, defined England, at best, as a middleweight in a world dominated by two heavyweights. -

The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71 Christopher Gerard Kinsella Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Recommended Citation Kinsella, Christopher Gerard, "The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71" (1974). Dissertations. 1378. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1378 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Christopher Gerard Kinsella THE DIPLOMATIC MISSION OF ARCHBISHOP FLAVIO CHIGI APOSTOLIC NUNCIO TO PARIS, 1870-71 by Christopher G. Kinsella t I' A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty:of the Graduate School of Loyola Unive rsi.ty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February, 197 4 \ ' LIFE Christopher Gerard Kinsella was born on April 11, 1944 in Anacortes, Washington. He was raised in St. Louis, where he received his primary and secondary education, graduating from St. Louis University High School in June of 1962, He received an Honors Bachelor of Arts cum laude degree from St. Louis University,.., majoring in history, in June of 1966 • Mr. Kinsella began graduate studies at Loyola University of Chicago in September of 1966. He received a Master of Arts (Research) in History in February, 1968 and immediately began studies for the doctorate. -

Diplomatic Processes and Cultural Variations: the Relevance of Culture in Diplomacy

Diplomatic Processes and Cultural Variations: The Relevance of Culture in Diplomacy by Wilfried Bolewski Let us not be blind to our differences—but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot now end our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. John F. Kennedy, American University, June 10, 1963. The relationship between diplomacy and culture has been somewhat neglected in recent academic and practical studies,1 even though competence and understanding during intercultural exchanges unites societies and facilitates further intercultural interactions. Current public discussions concentrate exclusively on the existence of cultural commonalities and universal values all cultures share.2 However, determining likenesses among cultures should be secondary to the awareness of cultural differences as the logical starting point for the evaluation of intercultural commonalities. Intercultural sensitivity within groups paves the way for the acceptance and tolerance of other cultures and allows members to be open to values which are universal among all groups, such as law and justice, which globalized society should then build upon together. Facing the challenges of an increasingly complex world, the question of interdependency between diplomatic processes and cultural variations becomes relevant: is there a shared professional culture in diplomacy apart from national ones, and if so, does it influence diplomacy? To what extent can research into national cultures help diplomacy and governments to understand international interactions? DEFINITION OF “CULTURE”3 General definition Before analyzing the interdependency between culture and diplomacy, it is necessary to state what the word culture implies. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Introduction In his poem, The Second Coming (1919), William Butler Yeats captured the moment we are now experiencing: Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. As we see the deterioration of the institutions created and fostered after the Second World War to create a climate in which peace and prosperity could flourish in Europe and beyond, it is important to understand the role played by diplomacy in securing the stability and strengthening the shared values of freedom and democracy that have marked this era for the nations of the world. It is most instructive to read the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy, in which he encouraged Americans not only to do good things for their own country, but to do good things in the world. The creation of the Peace Corps is an example of the kind of spirit that put young American volunteers into some of the poorest nations in an effort to improve the standard of living for people around the globe. We knew we were leaders; we knew that we had many political and economic and social advantages. There was an impetus to share this wealth. Generosity, not greed, was the motivation of that generation. Of course, this did not begin with Kennedy. It was preceded by the Marshall Plan, one of the only times in history that the conqueror decided to rebuild the country of the vanquished foe. -

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article. -

Toward a New Diplomatic History of Medieval and Early Modern Europe

a Toward a New Diplomatic History of Medieval and Early Modern Europe John Watkins University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota The time has come for a multidisciplinary reevaluation of one of the old- est, and traditionally one of the most conservative, subfields in the modern discipline of history: the study of premodern diplomacy. Diplomatic studies are often bracketed aside from other areas of investigation and seem imper- meable to theoretical and methodological innovations that have transformed almost every other sector of the profession. Scholars interested in race, eth- nicity, gender, sexuality, subalternity, and new modes of intellectual history have occasionally used diplomatic sources, but they have rarely investigated the diplomatic practices that created those sources in the first place. The modern cross-disciplinary study of international relations has broadened the discussion of diplomatic issues for later historical periods, but the presentist biases of that conversation — centered on nineteenth-century understand- ings of the nation — have limited its application to the medieval and early modern periods. Nor has diplomacy figured significantly in the dialogue with his- tory that has transformed literary studies within the last three decades. In some ways, nothing could be stranger than the literary critic’s lack of atten- tion to diplomatic theory and practice. Many of the most familiar figures in European literary canons spent a significant portion of their career in diplomatic service, such as Petrarch, Chaucer, Wyatt, Sidney, Tasso, and Montaigne. Diplomacy also figures in the careers of newly discovered and newly rediscovered women writers such as Veronica Gàmbara and Margue- rite de Navarre. But an emphasis on power relationships within individual polities characterizes literary study in the wake of new historicism. -

United Nations List of Delegations to the Second High-Level United

United Nations A/CONF.235/INF/2 Distr.: General 30 August 2019 Original: English Second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation Buenos Aires, 20–22 March 2019 List of delegations to the second High-level United Nations Conference on South-South Cooperation 19-14881 (E) 110919 *1914881* A/CONF.235/INF/2 I. States ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Gent Cakaj, Acting Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs H.E. Ms. Besiana Kadare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative Mr. Dastid Koreshi, Chief of Staff of the Acting Foreign Minister ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Abdallah Baali, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alternate Head of Delegation H.E. Mr. Benaouda Hamel, Ambassador of Algeria in Argentina, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina Representatives Mr. Nacim Gaouaoui, Deputy Director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Zoubir Benarbia, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Algeria to the United Nations Mr. Mohamed Djalel Eddine Benabdoun, First Secretary, Embassy of Algeria in Argentina ANDORRA Mrs. Gemma Cano Berne, Director for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation Mrs. Julia Stokes Sada, Desk Officer for International Cooperation for Development ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Manuel Nunes Junior, Minister of State for Social and Economic Development, Angola Representatives H.E. Mr. Domingos Custodio Vieira Lopes, Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Angola H.E. Ms. Maria de Jesus dos Reis Ferreira, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Angola to the United Nations ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA H.E. Mr. Walton Alfonso Webson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission Representative Mr. Claxton Jessie Curtis Duberry, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission 2/42 19-14881 A/CONF.235/INF/2 ARGENTINA H.E. -

Espionage and the Forfeiture of Diplomatic Immunity

NATHANIEL P. WARD* Espionage and the Forfeiture of Diplomatic Immunity When nations conduct intercourse beyond their territorial boundaries, the need for transnational representation is fundamental if national objectives are to be accomplished. To accommodate this need, the world community has provided a special regime for diplomats, consuls and representatives to inter- national organizations.' That regime accords certain privileges and immunities in the receiving state2 to protect the sending state's unhampered conduct of foreign relations3 and to avoid embarrassment for its government.' The sources of these privileges and immunities are found in the customary practice of nations, the domestic laws of the receiving states' and multinational 6 and bilateral' treaties. This diplomatic grant confers criminal and civil immunity *B.A., Virginia Military Institute; J.D. California Western School of Law. A retired army cap- tain in military intelligence, Mr. Ward is currently a clerk for a federal magistrate in San Diego. 'J.L. BRIERLY, THE LAW OF NATIONS 255 (6th ed. 1963). 'RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF FOREIGN RELATIONS LAW OF THE UNITED STATES, § 63, comment c at 195 (1965): The term "privileges and immunities" is often used in international law without differentiation between its two constituents. To the extent that any distinction is made between the two, there is a tendency to use "privilege" in referring to a right which is affirmatively described, such as the right to employ diplomatic couriers, and to use "immunity" in referring to a right which is described in a negative sense, such as freedom of diplomatic envoys from prosecution. As used in the Restatement of this Subject, the term "immunity" includes both, although the term "privileges and immunities" is retained when it conforms to existing practice. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 2014

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2014 GREENING EMBASSIES CHIEf-Of-MISSION GUIDELINES HOW H.A. GILES LEARNED CHINESE FOREIGN April 2014 SERVICE Volume 91, No. 4 AFSA NEWS FOCUS GREENING EMBASSIES AFSA Releases Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 45 Eco-Diplomacy: Building the Foundation / 20 VP Voice State: Collaborating with Our Partner Organizations / 46 U.S. embassies and consulates around the world are becoming showcases VP Voice Retiree: Retirement for American leadership in best practices and sustainable technology. Begins Before Retirement / 47 BY DONNA M. MCINTIRE VP Voice FCS: The Budget Resource Merry-Go-Round / 48 The Greening Diplomacy Initiative: Chief-of-Mission Guidelines / 49 Capturing Innovation / 24 AFSA Hosts Chiefs of Mission / 51 AFSA On the Hill: State’s homegrown Greening Diplomacy Initiative relies on seeding, Beyond Advocacy Day / 52 harvesting, sifting, implementing and sharing employees’ innovations New Association Management and ideas, large and small. System for AFSA / 53 BY CAROLINE D’ANGELO AFSA VP Meets with Florida Retirees / 54 The League of Green Embassies: 2013 Sinclaire Award Recipients / 54 AFSA Book Notes: American Leadership in Sustainability / 30 America’s First Globals / 55 A coalition of more than 100 U.S. embassies and consulates worldwide AFSA Partners with United Nations shares ideas and practical experience in the field. Association / 56 BY JOHN DAVID MOLESKY FSJ Editor-in-Chief Steps Down / 56 AFSA and DACOR Salute U.S. Marine Security Guards / 57 Finns Take the LEED in Green Embassy Design / 35 The Foreign Service Family: The Finnish embassy in Washington, D.C., is a green building that The Packout and Me / 59 was ahead of its time. -

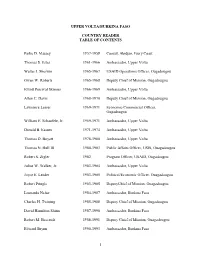

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay.