Law Reform in Post-Sukarno Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gus Dur, As the President Is Usually Called

Indonesia Briefing Jakarta/Brussels, 21 February 2001 INDONESIA'S PRESIDENTIAL CRISIS The Abdurrahman Wahid presidency was dealt a devastating blow by the Indonesian parliament (DPR) on 1 February 2001 when it voted 393 to 4 to begin proceedings that could end with the impeachment of the president.1 This followed the walk-out of 48 members of Abdurrahman's own National Awakening Party (PKB). Under Indonesia's presidential system, a parliamentary 'no-confidence' motion cannot bring down the government but the recent vote has begun a drawn-out process that could lead to the convening of a Special Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) - the body that has the constitutional authority both to elect the president and withdraw the presidential mandate. The most fundamental source of the president's political vulnerability arises from the fact that his party, PKB, won only 13 per cent of the votes in the 1999 national election and holds only 51 seats in the 500-member DPR and 58 in the 695-member MPR. The PKB is based on the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a traditionalist Muslim organisation that had previously been led by Gus Dur, as the president is usually called. Although the NU's membership is estimated at more than 30 million, the PKB's support is drawn mainly from the rural parts of Java, especially East Java, where it was the leading party in the general election. Gus Dur's election as president occurred in somewhat fortuitous circumstances. The front-runner in the presidential race was Megawati Soekarnoputri, whose secular- nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) won 34 per cent of the votes in the general election. -

Hans Harmakaputra, Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia

Key Issues in Religion and World Affairs Interfaith Relations in Contemporary Indonesia: Challenges and Progress Hans Abdiel Harmakaputra PhD Student in Comparative Theology, Boston College I. Introduction In February 2014 Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) published a report concerning the rise of religious intolerance across Indonesia. Entitled Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,1 this study portrays the problems plaguing interfaith relations in Indonesia, where many religious minorities suffer from persecution and injustice. The report lists five main factors contributing to the rise of religious intolerance: (1) the spread of extremist ideology through media channels, such as the internet, religious pamphlets, DVDs, and other means, funded from inside and outside the country; (2) the attitude of local, provincial, and national authorities; (3) the implementation of discriminatory laws and regulations; (4) weakness of law enforcement on the part of police and the judiciary in cases where religious minorities are victimized; and (5) the unwillingness of a “silent majority” to speak out against intolerance.2 This list of factors shows that the government bears considerable responsibility. Nevertheless, the hope for a better way to manage Indonesia’s diversity was one reason why Joko Widodo was elected president of the Republic of Indonesia in October 2014. Joko Widodo (popularly known as “Jokowi”) is a popular leader with a relatively positive governing record. He was the mayor of Surakarta (Solo) from 2005 to 2012, and then the governor of Jakarta from 2012 to 2014. People had great expectations for Jokowi’s administration, and there have been positive improvements during his term. However, Human Rights Watch (HRW) World Report 2016 presents negative data regarding his record on human rights in the year 2015, including those pertaining to interfaith relations.3 The document 1 The pdf version of the report can be downloaded freely from Christian Solidarity Worldwide, “Indonesia: Pluralism in Peril,” February 14, 2014. -

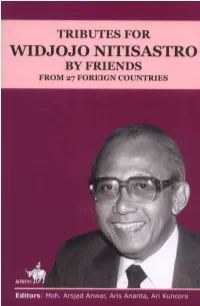

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

BAB II DESKRIPSI OBYEK PENELITIAN A. Dari Singasari

BAB II DESKRIPSI OBYEK PENELITIAN A. Dari Singasari Sampai PIM Sejarah singkat berdirinya kerajaan Majapahit, penulis rangkum dari berbagai sumber. Kebanyakan dari literatur soal Majapahit adalah hasil tafsir, interpretasi dari orang per orang yang bisa jadi menimbulkan sanggahan di sana- sini. Itulah yang penulis temui pada forum obrolan di dunia maya seputar Majapahit. Masing-masing pihak merasa pemahamannyalah yang paling sempurna. Maka dari itu, penulis mencoba untuk merangkum dari berbagai sumber, memilih yang sekiranya sama pada setiap perbedaan pandangan yang ada. Keberadaan Majapahit tidak bisa dilepaskan dari kerajaan Singasari. Tidak hanya karena urutan waktu, tapi juga penguasa Majapahit adalah para penguasa kerajaan Singasari yang runtuh akibat serangan dari kerajaan Daha.1 Raden Wijaya yang merupakan panglima perang Singasari kemudian memutuskan untuk mengabdi pada Daha di bawah kepemimpinan Jayakatwang. Berkat pengabdiannya pada Daha, Raden Wijaya akhirnya mendapat kepercayaan penuh dari Jayakatwang. Bermodal kepercayaan itulah, pada tahun 1292 Raden Wijaya meminta izin kepada Jayakatwang untuk membuka hutan Tarik untuk dijadikan desa guna menjadi pertahanan terdepan yang melindungi Daha.2 Setelah mendapat izin Jayakatwang, Raden Wijaya kemudian membabat hutan Tarik itu, membangun desa yang kemudian diberi nama Majapahit. Nama 1 Esa Damar Pinuluh, Pesona Majapahit (Jogjakarta: BukuBiru, 2010), hal. 7-14. 2 Ibid., hal. 16. 29 Majapahit konon diambil dari nama pohon buah maja yang rasa buahnya sangat pahit. Kemampuan Raden Wijaya sebagai panglima memang tidak diragukan. Sesaat setelah membuka hutan Tarik, tepatnya tahun 1293, ia menggulingkan Jayakatwang dan menjadi raja pertama Majapahit. Perjalanan Majapahit kemudian diwarnai dengan beragam pemberontakan yang dilakukan oleh para sahabatnya yang merasa tidak puas atas pembagian kekuasaannya. Sekali lagi Raden Wijaya membuktikan keampuhannya sebagai seorang pemimpin. -

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: the Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: The Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015 Taufiqurrahman, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia Budi Endarto, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Business and Public Policy 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The Head of the State Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Summit of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2007 on Cebu, Manila agreed to accelerate the implementation of ASEAN Economy Community (AEC), which was originally 2020 to 2015. This means that within the next seven months, the people of Indonesia and ASEAN member countries more integrated into one large house named AEC. This in turn will further encourage increased volume of international trade, both by the domestic consumers to foreign businesses, among foreign consumers by domestic businesses, as well as between foreign entrepreneurs with domestic businesses. As a result, the potential for legal disputes between the parties in international trade transactions can not be avoided. Therefore, the existence of the contract law of international commercial law in order to provide maximum protection for the parties to a transaction are indispensable. The existence of this legal regime will provide great benefit to all parties to a transaction to minimize disputes. This study aims to assess the significance of the governing of International Commercial Contract Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 and also to find legal principles underlying governing the International Commercial Contracts Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 so as to provide a valuable contribution to the development of Indonesian national law. -

Bab Ii Deskripsi Pt. Sirkulasi Kompas Gramedia

BAB II DESKRIPSI PT. SIRKULASI KOMPAS GRAMEDIA A. Sekilas Perkembangan Kompas Gramedia A.1. Kompas Gramedia Kompas Gramedia (KG) merupakan sebuah perusahaan inti yang membawahi sirkulasi kompas gramedia dan beberapa unit bisnis di Indonesia yang bekerja sama secara langsung dengan Kompas Gramedia. Beranjak dari sejarahnya, Kompas Gramedia sebagai salah satu perusahaan yang terkemuka di Indonesia memiliki peristiwa-peristiwa penting yang menjadi tonggak perjalanan dari sejak berdiri sampai perkembangannya saat ini. Pada tanggal 17 Agustus 1963 terbitlah majalah bulanan intisari oleh Petrus Kanisius dan Jakob Oetama bersama J. Adisubrata dan Irawati SH. Majalah bulanan intisari bertujuan memberikan bacaan untuk membuka cakrawala bagi masyarakat Indonesia. pada saat itu, intisari terbit dengan tampilan hitam putih, tanpa sampul berukuran 14 x 17,5 cm dengan tebal halaman 128 halaman dan majalah ini mendapat sambutan baik dari pembaca dan mencapai oplah 11.000 eksemplar. Pada perkembangan industri printing di masa kini yang bersaing dengan waktu dan teknologi, Kompas Gramedia siap menerima tuntutan dan tantangan dunia sebagai penyedia jasa informasi dengan menyediakan berbagai sarana media seperti surat kabar, majalah, tabloid, 46 buku, radio, media on-line, televisi, karingan toko buku, dan sarana pendidikan. Kompas Gramedia juga hadir di usaha lain seperti jaringan hotel, jaringan percetakan, tempat pameran, kegiatan kebudayaan, pelaksana acara, properti, dan manufaktur (pabrik tissue dan popok). Semua itu menyatu dalam sebuah jaringan media komunikasi terpadu yang pada saat ini sedang melakukan transformasi bisnis berdasarkan nilai-nilai yang diwariskan para pendirinya yang dimanifestasikan dalam KG Values, yaitu 5C : Caring, Credible, Competent, Competitive, Customer Delight untuk menggapai visi dan misi : “Menjadi perusahaan yang terbesar, terbaik, terpadu, dan tersebar di Asia Tenggara melalui usaha berbasis pengetahuan yang menciptakan masyarakat terdidik, tercerahkan, menghargai kebhinekaan dan adil sejahtera”. -

City Architecture As the Production of Urban Culture: Semiotics Review for Cultural Studies

HUMANIORA VOLUME 30 Number 3 October 2018 Page 248–262 City Architecture as the Production of Urban Culture: Semiotics Review for Cultural Studies Daniel Susilo; Mega Primatama Universitas dr. Soetomo, Indonesia; University College London, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article aims to describe the correlation between city’s architecture as urban culture and cultural studies, specifically in semiotics. This article starts with Chris Barker’s statement about city and urban as text in his phenomenal book, Cultural Studies, Theory and Practice. The city as a complex subject has been transformed into the representation of urban culture. In the post-modernism view, urban culture as cultural space and cultural studies’ sites have significantly pointed to became communications discourse and also part of the identity of Semiology. This article uses semiotics of Saussure for the research methods. Surabaya and Jakarta have been chosen for the objects of this article. The result of this article is describing the significant view of architecture science helps the semiotics in cultural studies. In another way, city’s architecture becomes the strong identity of urban culture in Jakarta and Surabaya. Architecture approaches the cultural studies to view urban culture, especially in symbol and identity in the post-modernism era. Keywords: city’s architecture; urban culture; semiotics; cultural studies INTRODUCTION Giddens (1993) in Lubis (2014:4) stated the society urbanization, a city that used to be not that big become is like a building who need reconstruction every day so large that has to prop up the need of its growing and human-created their reconstruction. -

Living Adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: a Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana

Living adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: A Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana Biodata: A lecturer at Lambung Mangkurat University, South Kalimantan, Indonesia and is currently pursuing a Ph.D in Law at T.C Beirne, School of Law, The University of Queensland, Australia. The author’s profile can be viewed at: http://www.law.uq.edu.au/rhd-student- profiles. Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines legal pluralism’s discourse in Indonesia which experiences challenges from within. The strong influence of civil law tradition may hinder the reconciliation processes between the Indonesian living law, namely adat law, and the State legal system which is characterised by the strong legal positivist (formalist). The State law fiercely embraces the spirit of unification, discretion-limiting in legal reasoning and strictly moral-rule dichotomies. The first part of this paper aims to reveal the appropriate terminologies in legal pluralism discourse in the context of Indonesian legal system. The second part of this paper will trace the historical and dialectical development of Indonesian legal pluralism, by discussing the position taken by several scholars from diverse legal paradigms. This paper will demonstrate that philosophical reform by shifting from legalism and developmentalism to legal pluralism is pivotal to widen the space for justice for the people, particularly those considered to be indigenous peoples. This paper, however, only contains theoretical discourse which was part of pre-liminary -

Soekarno's Political Thinking About Guided Democracy

e-ISSN : 2528 - 2069 SOEKARNO’S POLITICAL THINKING ABOUT GUIDED DEMOCRACY Author : Gili Argenti and Dini Sri Istining Dias Government Science, State University of Singaperbangsa Karawang (UNSIKA) Email : [email protected] and [email protected] ABSTRACT Soekarno is one of the leaders of the four founders of the Republic of Indonesia, his political thinking is very broad, one of his political thinking about democracy is guided democracy into controversy, in his youth Soekarno was known as a very revolutionary, humanist and progressive figure of political thinkers of his day. His thoughts on leading democracy put his figure as a leader judged authoritarian by his political opponents. This paper is a study of thought about Soekarno, especially his thinking about the concept of democracy which is considered as a political concept typical of Indonesian cultures. Key word: Soekarno, democracy PRELIMINARY Soekarno is one of the four founders of the Republic of Indonesia according to the version of Tempo Magazine, as political figures aligned with Mohammad Hatta, Sutan Sjahrir and Tan Malaka. Soekarno's thought of national politics placed himself as a great thinker that Indonesian ever had. In the typology of political thought, his nationality has been placed as a radical nationalist thinker, since his youthful interest in politics has been enormous. As an active politician, Soekarno poured many of his thinkers into speeches, articles and books. One of Soekarno's highly controversial and inviting notions of polemic up to now is the political thought of guided democracy. Young Soekarno's thoughts were filled with revolutionary idealism and anti-oppression, but at the end of his reign, he became a repressive and anti-democratic thinker. -

Industrial Policy in Indonesia a Global Value Chain Perspective

Industrial Policy in Indonesia A Global Value Chain Perspective This paper traces the evolution of industrial policies in Indonesia from a global value chain (GVC) perspective. As the gains of a country participation in GVC are influenced, among others, by industrial policies, an understanding of both policy leverage and risks is imperative. Using the mineral sector as a mini case study, the paper assesses the Indonesian Government’s recent effort to boost domestic value addition in the sector. It argues that the effectiveness of government policies in maximizing the gains from GVC participation depends not only on policy design, but also on policy consistency and coherence, effective implementation, and coordination. About the Asian Development Bank InDustrIAl PolIcy In ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 InDonesIA: A GloBAl a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. VAlue chAIn PersPectIVe Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Julia Tijaja and Mohammad Faisal no. 411 adb economics october 2014 working paper series AsiAn Development BAnk 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org ADB Economics Working Paper Series Industrial Policy in Indonesia: A Global Value Chain Perspective Julia Tijaja and Mohammad Faisal Julia Tijaja ([email protected]) is an Assistant Director and Senior Economist at the ASEAN No. -

Airport Expansion in Indonesia

Aviation expansion in Indonesia Tourism,Aerotropolis land struggles, economic Update zones and aerotropolis projects By Rose Rose Bridger Bridger TWN Third World Network June 2017 Aviation Expansion in Indonesia Tourism, Land Struggles, Economic Zones and Aerotropolis Projects Rose Bridger TWN Global Anti-Aerotropolis Third World Network Movement (GAAM) Aviation Expansion in Indonesia: Tourism, Land Struggles, Economic Zones and Aerotropolis Projects is published by Third World Network 131 Jalan Macalister 10400 Penang, Malaysia www.twn.my and Global Anti-Aerotropolis Movement c/o t.i.m.-team PO Box 51 Chorakhebua Bangkok 10230, Thailand www.antiaero.org © Rose Bridger 2017 Printed by Jutaprint 2 Solok Sungai Pinang 3 11600 Penang, Malaysia CONTENTS Abbreviations...........................................................................................................iv Notes........................................................................................................................iv Introduction..............................................................................................................1 Airport Expansion in Indonesia.................................................................................2 Aviation expansion and tourism.........................................................................................2 Land rights struggles...........................................................................................................3 Protests and divided communities.....................................................................................5