Technology and Scaling of Ultrathin Body Double-Gate Fets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Performance Power Distribution Networks with On-Chip Decoupling Capacitors for Nanoscale Integrated Circuits

High Performance Power Distribution Networks with On-Chip Decoupling Capacitors for Nanoscale Integrated Circuits by Mikhail Popovich Submitted in Partial Ful¯llment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Supervised by Professor Eby G. Friedman Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering The College School of Engineering and Applied Sciences University of Rochester Rochester, New York 2007 ii It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity. | Albert Einstein iii Dedication This work is dedicated to my parents, Mr. Evgeniy Antonovich and Mrs. Lyud- mila Mikhailovna, my wife Oksana, and my daughter Elizabeth Michelle. iv Curriculum Vitae Mikhail Popovich was born in Izhevsk, Russia in 1975. He received the B.S. degree in electrical engineering from Izhevsk State Technical University, Izhevsk, Russia in 1998, and the M.S. degree in electrical and computer engineering from the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY in 2002, where he is completing the Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering. He was an intern at Freescale Semiconductor Corporation, Tempe, AZ, in the summer 2005, where he worked on signal integrity in RF and mixed-signal ICs and developed design techniques and methodologies for placing distributed on-chip de- coupling capacitors. His professional experience also includes characterization of sub- strate and interconnect crosstalk noise in CMOS imaging circuits for the Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY. He has authored a book and several conference and journal papers in the areas of power distribution networks in CMOS VLSI circuits, placement of on-chip decoupling capacitors, and the inductive properties of on-chip v interconnect. His research interests are in the areas of on-chip noise, signal integrity, and interconnect design including on-chip inductive e®ects, optimization of power distribution networks, and the design of on-chip decoupling capacitors. -

Introduction to the Course. in This Lecture I Would Try to Set the Course in Perspective

Introduction to the course. In this lecture I would try to set the course in perspective. Before we embark on learning something, it is good to ponder why it would be interesting, besides the fact that it can fetch useful course credits. What do you understand by VLSI? In retrospect, integrated circuits having 10s of devices were called small scale integrated circuits (SSI), a few hundreds were called medium scale few thousands large scale. The game stopped with VLSI as people lost the count (not really). What does the word VLSI bring to your mind? Discussion to follow. What do you understand by technology? Discussion to follow. Technology is the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes. For example, why you may not call VLSI circuit design as VLSI technology? This is by convention in the semiconductor business research and business community. The convention is to treat fabrication technology as the “technology”. In this course we would discuss and try to learn how Silicon Integrated Circuits are fabricated. Integrated circuits are fabricated by a sequence of fabrication steps called unit processes. A unit process would add to or subtract from a substrate. Examples of unit processes can be cleaning of a wafer, deposition of a thin film of a material and so on. The unit processes are not uniquely applied to VLSI fabrication only. I can combine several of these unit processes to make solar cells. I can do same for making MEMS devices. So the unit processes can be thought of as pieces in a jigsaw puzzles. The outcome would depend on how you sequence the unit processes. -

MOSFET - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

MOSFET - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOSFET MOSFET From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET, MOS-FET, or MOS FET), is by far the most common field-effect transistor in both digital and analog circuits. The MOSFET is composed of a channel of n-type or p-type semiconductor material (see article on semiconductor devices), and is accordingly called an NMOSFET or a PMOSFET (also commonly nMOSFET, pMOSFET, NMOS FET, PMOS FET, nMOS FET, pMOS FET). The 'metal' in the name (for transistors upto the 65 nanometer technology node) is an anachronism from early chips in which the gates were metal; They use polysilicon gates. IGFET is a related, more general term meaning insulated-gate field-effect transistor, and is almost synonymous with "MOSFET", though it can refer to FETs with a gate insulator that is not oxide. Some prefer to use "IGFET" when referring to devices with polysilicon gates, but most still call them MOSFETs. With the new generation of high-k technology that Intel and IBM have announced [1] (http://www.intel.com/technology/silicon/45nm_technology.htm) , metal gates in conjunction with the a high-k dielectric material replacing the silicon dioxide are making a comeback replacing the polysilicon. Usually the semiconductor of choice is silicon, but some chip manufacturers, most notably IBM, have begun to use a mixture of silicon and germanium (SiGe) in MOSFET channels. Unfortunately, many semiconductors with better electrical properties than silicon, such as gallium arsenide, do not form good gate oxides and thus are not suitable for MOSFETs. -

Transistors to Integrated Circuits

resistanc collectod ean r capacit foune yar o t d commercial silicon controlled rectifier, today's necessarye b relative .Th e advantage lineaf so r thyristor. This later wor alss kowa r baseou n do and circular structures are considered both for 1956 research [19]. base resistanc r collectofo d an er capacity. Parameters, which are expected to affect the In the process of diffusing the p-type substrate frequency behavior considerede ar , , including wafer into an n-p-n configuration for the first emitter depletion layer capacity, collector stage of p-n-p-n construction, particularly in the depletion layer capacit diffusiod yan n transit redistribution "drive-in" e donophasth f ro e time. Finall parametere yth s which mighe b t diffusion at higher temperature in a dry gas obtainabl comparee ear d with those needer dfo ambient (typically > 1100°C in H2), Frosch a few typical switching applications." would seriously damag r waferseou wafee Th . r surface woul e erodedb pittedd an d r eveo , n The Planar Process totally destroyed. Every time this happenee dth s e apparenlosexpressiowa th s y b tn o n The development of oxide masking by Frosch Frosch' smentiono t face t no , ourn o , s (N.H.). and Derick [9,10] on silicon deserves special We would make some adjustments, get more attention inasmuch as they anticipated planar, oxide- silicon wafers ready, and try again. protected device processing. Silicon is the key ingredien oxids MOSFEr it fo d ey an tpave wa Te dth In the early Spring of 1955, Frosch commented integrated electronics [22]. -

Planar Process with Noyce’S Interconnection Via a Diffused Layer of Metal Conductors

Future Horizons Ltd Blakes Green Cottage TN15 0LQ, UK Tel: +44 1732 740440 Fax: +44 1732 608045 [email protected] www.futurehorizons.com Research Brief: 2019/01 – The Planar IC Process The Planar IC Process On 1 December 1957, Jean Hoerni, a Swiss physicist and Fairchild Semiconductor co-founder, recorded in his patent notebook an entry called "A method of protecting exposed p-n junctions at the surface of silicon transistors by oxide masking techniques." This was the first formal documentation of the planar semiconductor process, a radically new transistor design in which the oxide layer was left in place on the silicon wafer to protect the sensitive p-n junctions underneath. Focused on getting its first semiconductor devices into production, Fairchild did not pursue Hoerni’s planar approach at that time and it was not until 14 January 1959 that Hoerni finally wrote up his disclosure for what would become U.S. Patent 3025589. One week later, on 23 January 1959, Robert (Bob) Noyce, a fellow Fairchild co-founder, wrote up a disclosure for the planar IC. Fairchild’s first working planar IC was built some 16 months later in May 1960. Sixty years on, this technology remains the basis for virtually all semiconductor manufacturing today. The Early Days By the late 1950s, even though barely a decade old, transistors had already gone through several stages of development, including the material transition from germanium to silicon and the move from piece by piece to batch manufacturing through a simple photolithographic and Page 1 of 8 © Future Horizons 1989-2019, Reproduction Prohibited - All Rights Reserved The Planar IC Process The Global Semiconductor Industry Analysts Research Brief: 2019/01 etching technique known as the Mesa process. -

"Studies of Double-Diffused Transistor Structures" A

"STUDIES OF DOUBLE-DIFFUSED TRANSISTOR STRUCTURES" A THESIS presented for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON by RAYE EDWARD THOMAS June 1966 2. ABSTRACT The solid-state diffusion process is examined with particular reference to the idealized classical impurity distributions normally assumed to apply in diffused structures. The peculiar properties of the double-diffused structure (graded junctions and a maximum in base doping) are shown to effect an overall improvement in frequency per- formance. Methods used to derive information on the impurity profile both in large area devices (destructive techniques) and in small area devices (physical model derived from terminal measurements) are discussed. Early models are shown to be inadequate and strictly limited in applicability. A physical model (double exponential) is proposed to apply generally to double-diffused transistors. A detailed study of classical distributions establishes that the assumed model not only is a good representation of such distributions in the base region, but also accurately predicts depletion layer and base transport properties. The proper interpretation of terminal measurements allows the constants of the model to be successfully determined for actual transistors. Within the accuracy of the above-mentioned measurements, the derived model is concluded to be a good representation for actual devices. In conclusion, suggestions for further work are offered. 3. ACKNOWLEDGBENTS The author wishes to express his gratitude to his Supervisor, Professor A.R. Boothroyd of The Queen's University of Belfast, (formerly of Imperial College) for his support, guidance and encourangement during the course of the work described in this thesis. Grateful thanks are extended to his fellow research students for friendly and stimulating discussions, in particular, to Viphandh Roengpithya for additional assistance in the reproduction stage of the thesis. -

OBJECTIVES: 1- to Fabricate Bipolar Junction Transistors. 2

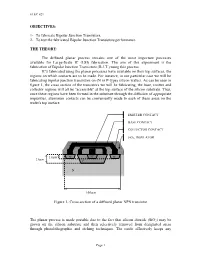

ELEC 421 OBJECTIVES: 1- To fabricate Bipolar Junction Transistors. 2- To test the fabricated Bipolar Junction Transistors performance. THE THEORY: The diffused planar process remains one of the most important processes available for Large-Scale IC (LSI) fabrication. The aim of this experiment is the fabrication of Bipolar Junction Transistors (B.J.T.) using this process. IC's fabricated using the planar processes have available on their top surfaces, the regions on which contacts are to be made. For instance, in our particular case we will be fabricating bipolar junction transistors on (N or P-type) silicon wafers. As can be seen in figure 1, the cross section of the transistors we will be fabricating, the base, emitter and collector regions will all be "accessible" at the top surface of the silicon substrate. Thus, once these regions have been formed in the substrate through the diffusion of appropriate impurities, aluminum contacts can be conveniently made to each of these areas on the wafer's top surface. EMITTER CONTACT BASE CONTACT COLLECTOR CONTACT SiO , INSULATOR 2 1.6m N+ N+ N+ 2.6m P+ N 100 m Figure 1- Cross-section of a diffused planar NPN transistor The planar process is made possible due to the fact that silicon dioxide (SiO2) may be grown on the silicon substrate and then selectively removed from designated areas through photolithographic and etching techniques. The oxide effectively keeps any Page 1 ELEC 421 doping impurities from diffusing into the areas it covers and thus permits the formation of P or N regions over well defined areas on the substrate's surface. -

The Role of Fairchild in Silicon Technology in the Early Days of “Silicon Valley”

The Role of Fairchild in Silicon Technology in the Early Days of “Silicon Valley” GORDON E. MOORE, LIFE FELLOW, IEEE Invited Paper Fairchild Semiconductor was founded in 1957 by a group aluminum that had been evaporated onto the silicon surface originating from Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, the first through the emitter layer, taking advantage of the fact that organization attempting to exploit silicon transistor technology the regrown silicon from the alloying step was doped with in the region at the base of the San Francisco peninsula now often referred to as “Silicon Valley.” Fairchild produced the aluminum to make an ohmic contact to the base, but a first commercial silicon mesa transistors and invented the rectifying junction with the n-type silicon constituted the “planar” process that formed the basis of practical integrated emitter layer. Individual transistor areas were separated by circuits. Several of the key directions in silicon device technology placing wax dots over a portion of the aluminum base originated at Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation and its successor organization, the Semiconductor Division of Fairchild contact and a portion of the exposed emitter region to act Camera and Instrument Corporation. This paper describes the as a mask and then etching through the emitter and base author’s recollections of some of the related events. diffused layers into the original n-type silicon. This resulted Keywords—Fairchild, Hoerni, integrated circuit, Noyce, planar, in an array of flat-topped transistors called mesas and, Shockley, transistor. hence, the mesa transistor. Since this was a batch process wherein the entire top surface of a silicon wafer could be processed at the same time to make several hopefully I. -

Evolutionary MOSFET Structure and Channel Design for Nanoscale CMOS Technology

Evolutionary MOSFET Structure and Channel Design for Nanoscale CMOS Technology by Byron Ho A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering – Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Tsu-Jae King Liu, Chair Professor Oscar Dubon Professor Vivek Subramanian Professor Ming Wu Fall 2012 Evolutionary MOSFET Structure and Channel Design for Nanoscale CMOS Technology Copyright © 2012 by Byron Ho Abstract Evolutionary MOSFET Structure and Channel Design for Nanoscale CMOS Technology by Byron Ho Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering – Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California, Berkeley Professor Tsu-Jae King Liu, Chair The constant pace of CMOS technology scaling has enabled continuous improvement in integrated-circuit cost and functionality, generating a new paradigm shift towards mobile computing. However, as the MOSFET dimensions are scaled below 30nm, electrostatic integrity and device variability become harder to control, degrading circuit performance. In order to overcome these issues, device engineers have started transitioning from the conventional planar bulk MOSFET toward revolutionary thin-body transistor structures such as the FinFET or fully- depleted silicon-on-insulator (FDSOI) MOSFET. While these alternatives appear to be elegant solutions, they require increased process complexity and/or more expensive starting substrates, making development and manufacturing costs a concern. For certain applications (such as mobile electronics), cost is still an important factor, inhibiting the quick adoption of the FinFET and FDSOI MOSFET structures while providing an opportunity to extend the competitiveness of planar bulk-silicon CMOS. A segmented-channel MOSFET (SegFET) design, which combines the benefits of both planar bulk MOSFETs (i.e. -

Key Steps to the Integrated Circuit- Autumn 1997

♦ Key Steps to the Integrated Circuit C. Mark Melliar-Smith, Douglas E. Haggan, and William W. Troutman This paper traces the key steps that led to the invention of the integrated circuit (IC). The first part of this paper reviews the steady improvements in the performance and fabrica- tion of single transistors in the decade after the Bell Labs breakthrough work in 1947. It sketches the various developments needed to produce a practical IC. Some of the discov- eries and developments discussed in the previous paper (“The Foundation of the Silicon Age” by Ian M. Ross) are briefly reviewed here to show how they fit on the critical path to the invention of the IC. In addition, the more advanced processes such as diffusion, oxide masking, photolithography, and epitaxy, which culminated in the planar process, are sum- marized. The early growth of the IC business is touched upon, along with a brief state- ment on the future limits of silicon IC technology. The second part of this paper sketches the various problems associated with the quality and reliability of this technology. The highlights of the semiconductor reliability story are reviewed from the early days of ger- manium and silicon transistors to the current metal-oxide semiconductor IC products. Also described are some of the process, packaging, and alpha particle problems that were encountered and solved before arriving at today’s semiconductor products. Introduction Improvements in the performance and fabrication ical innovations of the late fifties and early sixties. of single transistors occurred steadily in the decade Some of the discoveries discussed in the previous after the Bell Labs breakthrough work in 1947. -

Transistors to Integrated Circuits Howar

Fabe Th : o t b FroLa e mTh Transistors to Integrated Circuits Howar . HufdR f International SEMATECH 2706 Montopolis Drive Austin, TX 78741 Abstract. Transistor actio experimentalls nwa y observe Johy db n Bardee Walted nan r Brattai n-typn i e polycrystalline germanium on December 16, 1947 (and subsequently polycrystalline silicon) as a result of the judicious placement of gold-plated probe tip nearbn si y single crystal polycrystallingraine th f so e material (i.e. point-contace th , t semiconductor amplifier, often point-contace referreth s a o dt t transistor).The device configuration exploite inversioe dth ne layeth s a r channel through which most of the emitted (minority) carriers were transported from the emitter to the collector. The point-contact transistor was manufactured for ten years starting in 1951 by the Western Electric Division of AT&T. The a priori tuning of the point-contact transistor parameters, however, was not simple inasmuch as the device was dependent detailee onth d surface structure and, therefore, very sensitiv humidito et temperaturd yan s welea s exhibitina l g high noise levels. Accordingly, the devices differed significantly in their characteristics and electrical instabilities leading to "burnout" were not uncommon. With the implementation of crystalline semiconductor materials in the early 1950s, however, p-n junction (bulk) transistors began replacing the point-contact transistor, silicon began replacing germanium antransfee dth transistof o r r accelerated b technologfa e th shale o t W y.b l frola revie e m th historicae wth l rout whicy eb h single crystalline materials were develope accompanyine th d dan g methodologie transistof o s r fabrication, leadine th o gt Integratee onseth f o t d Circuit (1C) era. -

Fabrication of Detectors and Transistors on High-Resistivity Silicon

Fabrication of Detectors and Transistors on High-Resistivity Silicon Steve Holland Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory LBL—25520 University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 DE88 016240 ABSTRACT A new process for the fabrication of silicon p-i-n diode radiation detectors is described. The utilization of backside gettering in the fabrication process results in the actual physical removal of detrimental impurities from critical device regions. This reduces the sensitivity of detector properties to processing variables while yielding low diode reverse-leakage currents. In addition, gettering permits the use of processing tem peratures compatible with integrated-circuit fabrication. P-channel MOSFETs and sili con p-i-n diodes have been fabricated simultaneously on 10 kQ • cm <100> silicon using conventional integrated-circuit processing techniques. 1. Introduction The complexity and scale of many new applications for charged particle detectors, notably in high- energy physics, require well-controlled fabrication techniques. Local front-end and readout circuitry is essential for these systems, and monolithic integration of at least pan of this circuitry would greatly sim plify the readout system and increase performance and reliability [1]. Even on a smaller scale, devices such as the semiconductor drift chamber [2] would also benefit greatly from integrated front-ends by reducing the circuit capacitance in order to exploit the extremely low capacitance of these detectors. Hence, a modem detector process should offer minimum sensitivity to process-induced contaminants and ideally would be compatible with contemporary inlcgrated-circuit (IQ fabrication techniques. However, typical fabrication processes for radiation detectors do not fulfill cither of these goals. While in one notable case outstanding results have been achieved [3], the process used is incompatible with conventional IC fabrication and is very sensitive to the temperature at which the implanted dopants are annealed [4J.