To Write Is Bread. the Function of Writing for Edith Bruck*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AATI@Cagliari June 20 – 25, 2018 Accepted Sessions

AATI@Cagliari June 20 – 25, 2018 Accepted Sessions Session 57: I percorsi e i risultati della filologia deleddiana: verso una edizione nazionale dell’opera omnia. Organizzatore: Dino Manca (Università degli Studi di Sassari), ([email protected]). OBIETTIVI: La sessione proposta vuole essere un omaggio alla personalità e all’opera di Grazia Deledda. Tramite l’operazione artistica della scrittrice nuorese, culminata col premio Nobel (prima donna in Italia e seconda al mondo), la Sardegna è entrata, infatti, a far parte dell’immaginario europeo. Oggi gli studiosi hanno a loro disposizione una buona bibliografia che, soprattutto negli ultimi anni, ha – grazie agli apporti della filologia, della linguistica e dell’antropologia – aggiornato, se non riveduto e corretto, una vecchia vulgata critica che non di rado ha relegato la sua figura in ambiti esclusivamente nazionali se non addirittura regionali. Finalmente si può parlare, alla luce delle ultime ricerche, di una grande scrittrice europea di respiro universale. I nuovi studi, infatti, dimostrano (attraverso le inedite indagini sulla produzione, restituzione, circolazione e fruizione del testo) come e quanto la sua opera abbia nel Novecento rivestito un ruolo importante in un contesto internazionale, grazie alla sua capacità di suscitare nel lettore europeo (e non solo italiano) un bisogno di autenticità, grazie all’appassionata rappresentazione dell’«automodello» sardo e alla proiezione simbolica del suo universale concreto. Tuttavia, lo stato dell’arte evidenzia ancora importanti lacune nelle ricerche. Finora, ad esempio, si è dedicata scarsa attenzione alle relazioni tra la produzione precoce e i romanzi della maturità. Ci si dovrà sempre più applicare sulle questioni filologiche e linguistiche che, misurando l’impatto della variazione sulle diverse redazioni della medesima opera a distanza di decenni, potrebbero aiutarci a ricostruire porzioni importanti del quadro movimentato della stagione durante la quale la lingua degli italiani si andava assestando. -

Anti-Semitism on the Silver Screen: Pratolini's Short Story “Vanda”

Anti-Semitism on the Silver Screen: Pratolini’s Short Story “Vanda” and its Cinematic Adaptation(s) “Ora sapevamo. Cominciavamo a pensare.” “Now we knew. We were beginning to think.” (The final voiceover in the short film Roma ’38 [Dir. Sergio Capogna, 1954]) Originally published in 1947, the brief text “Vanda” by Vasco Pratolini, set during the period of the Race Laws in Italy, tells the story of the innocent, tentative romance that blossoms between an unnamed Florentine boy in his late teens and a young girl who hides her Jewish origins from him out of fear.1 This poignant work of prose, which is less than 1200 words in length, aligns Pratolini’s readers with the perspective of the naïf, Christian male protagonist who fails to comprehend the nature of his girlfriend’s struggles as she conceals her Jewish identity. Though he is seemingly obsessed with finding out her secret, a frequent subject in their conversations, the protagonist and narrator is convinced that Vanda’s reticence to introduce him to her father is merely a sign that the man disapproves of their relationship. Pratolini’s text only identifies Vanda’s family as Jewish during the final paragraph of this rather short work. Her death by suicide, motivated by the desperation she experiences as a result of the anti-Semitic Race Laws put in place by Mussolini’s fascist regime in 1938, is dealt with suddenly and concisely by the author in the final clause, in which he simply states that the river had “given back” Vanda’s corpse (Pratolini 30). -

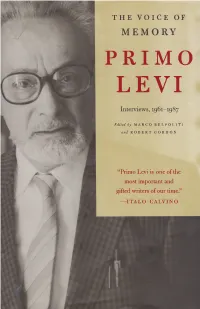

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Valerio Evangelisti Umberto Piersanti, Eugenio Guarini

Le interviste di Progetto Babele Valerio Evangelisti Umberto Piersanti, Eugenio Guarini L’impotenza delle parole nella scrittura di Banana Yoshimoto a cura di Salvatore Ciancitto Anticipazioni di un poeta visionario: Réné Barjavel a cura di V.Madio Lettera da Francoforte di Edith Bruck a cura di Fortuna Dalla Porta Del siciliano a cura di Marco Scalabrino Racconti di: Vittorio Catani, Paolo Durando, Peter Patti, Fabio Monteduro, Carlo Santulli, Fabrizio Ruggeri, Salvo Ferlazzo, Fabrizio Ulivieri, Giuliano Giachino, Giorgio Maggi e... tanti altri! TRADUCENDO TRADUCENDO: La Corrección de los Corderos di Fernando Sorrentino, trad. di Alessando Abate Progetto Babele Quindici EDITORIALE- pb15 a cura di Marco R. Capelli PROGETTO BABELE Un saluto, cordialissimo a tutti i lettori di Progetto Babele. [email protected] Vi sarete già accorti - non è difficile, basta una rapida occhiata all'indice - che questo PB15 è quasi un numero doppio. E, in un certo senso, me ne scuso con i lettori per- chè - è vero! - avevamo promesso di non farlo più. Ma era una promessa difficile da Capo Redattore: Marco R. Capelli mantenere, viste la quantità e la qualità del materiale che ci inviate e, soprattutto, la [email protected] passione con la quale, ancora, ci seguite. Una passione che persino queste cento (e due) pagine faticano a contenere. Coord.gruppo lettura: Claudio Palmieri Centodue pagine, dicevamo, di racconti, articoli e recensioni. Soprattutto recensioni. [email protected] Le recensioni di PB, cioè le recensioni dei libri che, confidando nel nostro giudizio, ci avete mandato in lettura. Diciotto recensioni, diciotto voci nuove (si può ancora dire Coord.gruppo recensione: Carlo Santulli "alternative"?) nel panorama letterario italiano, altrettante piacevoli sorprese. -

Nella Casa Dei Libri. 7 La Storia Raccontata

Nella Casa dei libri. 7 La storia raccontata: il vero e il verosimile del narratore Il ‘900: proposte di lettura Emigrazione Ulderico Bernardi, A catàr fortuna: storie venete, d’Australia e del Brasile, Vicenza, Neri e Pozza, 1994 Cesare Bermani, Al lavoro nella Germania di Hitler, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 1998 Piero Brunello, Pionieri. Gli italiani in Brasile e il mito della frontiera, Roma, Donzelli, 1994 Piero Brunello, Emigranti, in Storia d’Italia. Le regioni dall’unità ad oggi. Il Veneto, Torino, Einaudi, 1984 Savona - Straniero (a cura di), Canti dell’emigrazione, Milano, Garzanti, 1976 Emilio Franzina, Merica! Merica!, Verona, Cierre, 1994 Emilio Franzina, Dall’Arcadia in America, Torino, Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli, 1994 Paolo Cresci e Luciano Guidobaldi (a cura di), Partono i bastimenti, Milano, Mondadori, 1980 Elio Vittorini, Conversazione in Sicilia, Milano, Mondadori, 1980 Prima guerra mondiale Carlo Emilio Gadda, Giornale di guerra e di prigionia, Milano, Garzanti,1999 Emilio Lussu, Un anno sull’Altopiano, Torino, Einaudi, 1945 Paolo Monelli, Le scarpe al sole, Vicenza, Neri Pozza, 1994 Renato Serra, Lettere in pace e in guerra, Torino, Aragno, 2000 Mario Rigoni Stern, Storia di Tonle, Torino, Einaudi, 1978 Mario Rigoni Stern, L’anno della vittoria, Torino, Einaudi, 1985 Mario Rigoni Stern, Ritorno sul Don, Torino, Einaudi, 1973 Primo dopoguerra Corrado Alvaro, Gente in Aspromonte, Milano, Garzanti, 1970 Romano Bilenchi, Il capofabbrica, Milano, Rizzoli, 1991 Carlo Levi, Cristo si è fermato a Eboli, Torino, Einaudi, 1945 Mario Rigoni Stern, Le stagioni di Giacomo, Torino, Einaudi, 1995 Fascismo Vitaliano Brancati, Il bell’Antonio, Milano, Bompiani, 2001 Giorgio Boatti, Preferirei di no, Torino, Einaudi, 2001 Carlo Cassola, La casa di via Valadier, Milano, Rizzoli, 2001 Alba de Céspedes, Nessuno torna indietro, Milano, 1966 Vittorio Foa, Lettere della giovinezza. -

Sulla Collina Delle Muse. Gian Domenico Giagni E Sinisgalli 15

Edisud Salerno Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook, New York NUOVI PARADIGMI Collezione di Studi e Testi oltre i confini Diretta da Sebastiano Martelli Mario B. Mignone Franco Vitelli I volumi della Collezione sono sottoposti al preliminare vaglio scientifico di un comitato di referee anonimi Edisud Salerno Via Leopoldo Cassese, 26 Tel. e fax: 089 220899 84122 Salerno - Italia e-mail: [email protected] http://www.edisud.it IL SISTEMA DI QUALITÀ DELLA CASA EDITRICE È CERTIFICATO ISO 9001:2008 Forum Italicum Publishing Center for Italian Studies State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, N Y 11794-3358 - USA e-mail: [email protected] http://www.italianstudies.org Pubblicazione realizzata con un contributo della Regione Basilicata e dell’Università degli Studi “Aldo Moro” di Bari Edisud Salerno Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook New York Il guscio della chiocciola Studi su Leonardo Sinisgalli a cura di Sebastiano Martelli e Franco Vitelli con la collaborazione di Giulia Dell’Aquila e Laura Pesola 2° Nuovi Paradigmi 6 Collezione di studi e testi oltre i confini © 2012 Edisud Salerno ISBN 978-88-95154-90-9 © Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook, New York Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Il guscio della chiocciola. Studi su Leonardo Sinisgalli, a cura di Sebastiano Martelli e Franco Vitelli con la collaborazione di Giulia Dell’Aquila e Laura Pesola ISBN 1-893127-92-3 428 p. 27 cm.— 1. Leonardo Sinisgalli; 2. Italian Literature; 3. Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, Arts and Science; 4. Criticism and Interpretation I. Title II. Series L’editore è a disposizione di eventuali aventi diritto che non è riuscito a contattare Progetto di ingegneria del libro a geometria variabile di Mimmo Castellano Ricerca iconografica e impaginazione di Palmarosa Fuccella Indice del volume 2° Itinerario di un poeta 6 p. -

Uno Sguardo Sulla Letteratura Italiana Contemporanea

Paulina Matusz Università di Breslavia Uno sguardo sulla letteratura italiana contemporanea Literatura włoska w toku 2, a cura di Hanna Serkowska, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2011, 298 pp. Quando nel 2006 uscì in Polonia il volume Literatura włoska w toku (Let- teratura italiana in corso), si diceva che fosse una monografia speciale, una vera e propria rarità. I critici e recensori del libro sottolineavano che mai prima d’allora la letteratura italiana contemporanea fosse presentata al pubblico letterario polacco in maniera così dettagliata e ponderata. Si trattava infatti di un’interessante raccolta di articoli e saggi, scritti con l’ambizione di mostrare e descrivere il panorama letterario italiano nel modo più ampio possibile, presentando così i testi degli scrittori con- temporanei italiani anche ai lettori polacchi che fino allora solo sporadi- camente avevano avuto l’occasione di conoscere i libri più recenti degli autori provenienti dalla penisola italica . “Il fattore più importante che ha fatto nascere questa raccolta è stata la convinzione che della letteratura italiana in Polonia se ne scrive sem- pre troppo poco e troppo raramente”1 scriveva nell’introduzione al libro la curatrice del volume, professoressa Hanna Serkowska, giustifican- 1 H. Serkowska, Wprowadzenie, [in:] Literatura włoska w toku. O wybranych współczesnych pisarzach Italii, a cura di H. Serkowska, Zakład Narodowy im. Osso- lińskich, Wrocław 2006, p. 5. 164 Paulina Matusz do e spiegando così in qualche modo l’idea che aveva spinto l’intero gruppo di autori a scrivere e a raccogliere i loro testi in un unico libro. Sempre nella stessa introduzione era stato annunciato anche il volume successivo che avrebbe dovuto di lì a poco continuare l’opera di divul- gazione della moderna letteratura italiana in Polonia – che però è uscito solo alla fine del 2011, quindi ben cinque anni dopo la pubblicazione del primo libro. -

Dimensioni Sommario Rubriche In

INDICE CRONOLOGICO DEI SOMMARI a. I - 1957, 1 giugno, n. 1 La Redazione, Quasi un’introduzione, p. 3 Auguri per Dimensioni, p. 5: Gioacchino Volpe, p. 5 Ettore Paratore, p. 5 Giovanni Titta Rosa, p. 6 Laudomia Bonanni, p. 6 Mario Pomilio, p. 6 Laudomia Bonanni, Terremoto [racconto], p. 7 Fausto Brindesi, La crisi di un’epoca – 1. Monografie Sallustiane, p. 14 Ottaviano Giannangeli, Oltrecielo e oltre tempo: parole nuove in Montale, p. 19 Alfredo Postiglione, Tre streghe, dal Dizionario illustrato degli Incisori italiani [illustrazione], p. 24 Taverna delle Muse, p. 25 Giovanni Titta Rosa: Festa in Trastevere [poesia], p. 25 Forse questo ti giova [poesia], p. 26 Le Arti, p. 28 Pasquale Scarpitti, Remo Brindisi, p. 28 Giornale intimo [nota], p. 30 Giuseppe Bolino, Meditazione sulla cultura, p. 30 Ricordo di Maestri, p. 33: Ottaviano Giannangeli, Giuseppe De Robertis, p. 33 Giammario Sgattoni, Francesco Flora, p. 35 Biblioteca, p. 39 Giuseppe Sorge: Domenico Ciampoli romanziere, p. 39 o. g. [Ottaviano Giannangeli], Giammario Sgattoni: Poesie, p. 39 Giuseppe Rosato, Francesco Paolo Giancristofaro: Cesare De Titta nella poesia dialettale abruzzese, p. 40 a. I - 1957, luglio-agosto, n. 2-3 Mario Pomilio, Zia Clara [racconto], p. 3 Glauco Curci, I due volti dell’energia atomica. Il nostro tempo, p. 7 David Gazzani, L’incredibile Abruzzo. Urbanistica, p. 13 Ettore Paratore, Uno strano atteggiamento della cultura abruzzese, p. 25 Fausto Brindesi, La crisi di un’epoca – 2. Monografie Sallustiane, p. 36 Luigi Illuminati, Ovidio autobiografico e didascalico. Il bimillenario, p. 41 Ottaviano Giannangeli, Un amico del Petrarca [lettere a Barbato di Sulmona], p. -

ITALIAN BOOKSHELF Edited by Dino S

ITALIAN BOOKSHELF Edited by Dino S. Cervigni and Anne Tordi with the collaboration of Norma Bouchard, Paolo Cherchi, Gustavo Costa, Albert N. Mancini, Massimo Maggiari, and John P. Welle NOTES Mario Marti. Su Dante e il suo tempo con altri scritti di Italianistica. Galatina: Congedo Editore, 2009. Pp. 138. Testo del discorso tenuto dal Professor Giuseppe A. Camerino in occasione della cerimonia in onore del Professor Mario Marti nel giorno del compimento del suo 95o genetliaco. Lecce, 19 maggio 2009. Mario Marti dantista Nel porgere il mio augurio non solo sincero e profondo, ma anche e soprattutto commosso e molto partecipe per la festa per i primi 95 di un maestro e amico come Mario Marti vorrei dire, in tutta modestia, qualche parola sull‘ultima sua fatica di studioso insigne, consegnata al volume ancora freschissimo di stampa Su Dante e il suo tempo con altri scritti di Italianistica. Solo qualche parola su Marti studioso di Dante e della letteratura dell‘epoca di Dante, non essendo questa festa di stasera la sede di una presentazione vera e propria del volume in oggetto. Non prima però di qualche breve premessa. La presenza di scritti analitici e di pagine di discussione critica e filologica dedicate per lo più al Dante poeta è fin troppo evidente e costante in molti volumi di Marti. Si vedano almeno Realismo dantesco e altri studi, Milano Napoli, Ricciardi, 1961; Con Dante fra i poeti del suo tempo, Lecce, 1966; Con Dante fra i poeti del suo tempo, 1971, seconda edizione arricchita e riveduta; Dante, Boccaccio, Leopardi, Napoli, Liguori, 1980; Da Dante a Croce: proposte consensi dissensi, Congedo, Galatina, 2005 (Collana Dipartimento); Su Dante e il suo tempo con altri scritti di Italianistica, 2009, Congedo (Collana Dipartimento). -

Journal of Italian Translation

Journal of Italian Translation Journal of Italian Translation is an international journal devoted to the translation of literary works Editor from and into Italian-English-Italian dialects. All Luigi Bonaffini translations are published with the original text. It also publishes essays and reviews dealing with Italian Associate Editors translation. It is published twice a year. Gaetano Cipolla Michael Palma Submissions should be in electronic form. Trans- Joseph Perricone lations must be accompanied by the original texts Assistant Editor and brief profiles of the translator and the author. Paul D’Agostino Original texts and translations should be in separate files. All inquiries should be addressed to Journal of Editorial Board Italian Translation, Dept. of Modern Languages and Adria Bernardi Literatures, 2900 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210 Geoffrey Brock or [email protected] Franco Buffoni Barbara Carle Book reviews should be sent to Joseph Perricone, Peter Carravetta John Du Val Dept. of Modern Language and Literature, Fordham Anna Maria Farabbi University, Columbus Ave & 60th Street, New York, Rina Ferrarelli NY 10023 or [email protected] Luigi Fontanella Irene Marchegiani Website: www.jitonline.org Francesco Marroni Subscription rates: U.S. and Canada. Sebastiano Martelli Individuals $30.00 a year, $50 for 2 years. Adeodato Piazza Institutions $35.00 a year. Nicolai Single copies $18.00. Stephen Sartarelli Achille Serrao Cosma Siani For all mailing abroad please add $10 per issue. Marco Sonzogni Payments in U.S. dollars. Joseph Tusiani Make checks payable to Journal of Italian Trans- Lawrence Venuti lation. Pasquale Verdicchio Journal of Italian Translation is grateful to the Paolo Valesio Sonia Raiziss Giop Charitable Foundation for its Justin Vitiello generous support. -

2014 Modern Italian Narrator-Poets a New Critical

Allegoria_69-70_Layout 1 30/07/15 08:41:29 Pagina 1 (Nero pellicola) per uno studio materialistico della letteratura allegoria69-70 Allegoria_69-70_Layout 1 30/07/15 08:41:29 Pagina 2 (Nero pellicola) © G. B. Palumbo & C. Editore S.p.A. Palermo • Direttore responsabile • Redattori all’estero Franco Petroni International Editorial Board Andrea Inglese • Direttore Christian Rivoletti Editor Gigliola Sulis Romano Luperini Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia, • Redazione via Roma 56, 53100 Siena Editorial Assistants Anna Baldini • Comitato direttivo Università per Stranieri di Siena Executive Editors p.za Carlo Rosselli 27/28, 53100 Siena Pietro Cataldi e-mail: [email protected] Raffaele Donnarumma Valeria Cavalloro Guido Mazzoni Università di Siena via Roma 56, 53100 Siena • Redattori e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Valentino Baldi • Responsabile delle recensioni Alessio Baldini Book Review Editor Anna Baldini Daniela Brogi Daniele Balicco Università per Stranieri di Siena Daniela Brogi p.za Carlo Rosselli 27/28, 53100 Siena Riccardo Castellana e-mail: [email protected] Valeria Cavalloro Giuseppe Corlito • Amministrazione e pubblicità Tiziana de Rogatis Managing and Marketing Damiano Frasca via B. Ricasoli 59, 90139 Palermo, Margherita Ganeri tel. 091 588850 Alessandra Nucifora fax 091 6111848 Franco Petroni Guglielmo Pianigiani Gilda Policastro Felice Rappazzo Cristina Savettieri Michele Sisto progetto grafico Federica Giovannini Massimiliano Tortora impaginazione Fotocomp - Palermo Emanuele Zinato stampa Luxograph s.r.l. - Palermo Rivista semestrale Abbonamento annuo: Italia: € 35,00; Estero: € 45,00 Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Palermo n. 2 del 4 febbraio 1993 Prezzo di un singolo fascicolo: Italia: € 19,00; Estero: € 24,00 Annate e fascicoli arretrati costano il doppio ISSN 1122-1887 CCP 16271900 intestato a G.B. -

Giornata Della Memoria

Giornata della Memoria 27 gennaio Aggiornata a gennaio 2021 Bibliografia sulla Shoah a cura della Biblioteca comunale Lea Garofalo di Castelfranco Emilia Il Giorno della Memoria è una ricorrenza internazionale celebrata il 27 gennaio di ogni anno come giornata per commemorare le vittime dell'Olocausto. È stato così designato dalla risoluzione 60/7 dell'Assemblea generale delle Nazioni Unite del 1º novembre 2005, du- rante la 42ª riunione plenaria. La risoluzione fu preceduta da una sessio- ne speciale tenuta il 24 gennaio 2005 durante la quale l'Assemblea ge- nerale delle Nazioni Unite celebrò il sessantesimo anniversario della libe- razione dei campi di concentramento nazisti e la fine dell'Olocausto. Si è stabilito di celebrare il Giorno della Memoria ogni 27 gennaio perché in quel giorno del 1945 le truppe dell'Armata Rossa, impegnate nella offensiva Vifica-Oder in direzione della Germania, liberarono il campo di concentramento di Auschwitz. (Fonte: Wikipedia) Aprile Prova anche tu, una volta che ti senti solo o infelice o triste, a guardare fuori dalla soffitta quando il tempo è così bello. Non le case o i tetti, ma il cielo. Finché potrai guardare il cielo senza timori, sarai sicuro di essere puro dentro e tornerai ad essere Felice. (da Anna Frank) Saggistica Renato Moro, La chiesa e lo sterminio degli ebrei, Il Mulino 2002 (D. 261.26 MORO) Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Una questione morale: la Chiesa cattolica e l'olocausto, Mondadori 2003 (D. 261.8 GOLD) Elena Loewenthal, Scrivere di sé, identità ebraiche allo specchio, Einaudi 2007 (D. 305.892 4 LOEW) Gadi Luzzatto Voghera, Antisemitismo a sinistra, Einaudi 2007 (D.