Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AATI@Cagliari June 20 – 25, 2018 Accepted Sessions

AATI@Cagliari June 20 – 25, 2018 Accepted Sessions Session 57: I percorsi e i risultati della filologia deleddiana: verso una edizione nazionale dell’opera omnia. Organizzatore: Dino Manca (Università degli Studi di Sassari), ([email protected]). OBIETTIVI: La sessione proposta vuole essere un omaggio alla personalità e all’opera di Grazia Deledda. Tramite l’operazione artistica della scrittrice nuorese, culminata col premio Nobel (prima donna in Italia e seconda al mondo), la Sardegna è entrata, infatti, a far parte dell’immaginario europeo. Oggi gli studiosi hanno a loro disposizione una buona bibliografia che, soprattutto negli ultimi anni, ha – grazie agli apporti della filologia, della linguistica e dell’antropologia – aggiornato, se non riveduto e corretto, una vecchia vulgata critica che non di rado ha relegato la sua figura in ambiti esclusivamente nazionali se non addirittura regionali. Finalmente si può parlare, alla luce delle ultime ricerche, di una grande scrittrice europea di respiro universale. I nuovi studi, infatti, dimostrano (attraverso le inedite indagini sulla produzione, restituzione, circolazione e fruizione del testo) come e quanto la sua opera abbia nel Novecento rivestito un ruolo importante in un contesto internazionale, grazie alla sua capacità di suscitare nel lettore europeo (e non solo italiano) un bisogno di autenticità, grazie all’appassionata rappresentazione dell’«automodello» sardo e alla proiezione simbolica del suo universale concreto. Tuttavia, lo stato dell’arte evidenzia ancora importanti lacune nelle ricerche. Finora, ad esempio, si è dedicata scarsa attenzione alle relazioni tra la produzione precoce e i romanzi della maturità. Ci si dovrà sempre più applicare sulle questioni filologiche e linguistiche che, misurando l’impatto della variazione sulle diverse redazioni della medesima opera a distanza di decenni, potrebbero aiutarci a ricostruire porzioni importanti del quadro movimentato della stagione durante la quale la lingua degli italiani si andava assestando. -

Libri Per Tutti I Gusti

Consigli di lettura a cura della Biblioteca C. Pave C. se Biblioteca della cura a lettura di Consigli (José Saramago) Saramago) (José La fine di un viaggio è solo l'inizio di un altro altro un di l'inizio solo è viaggio un di fine La SAPORI LONTANI Aleksandr Litvinenko, Jurij Felstinskij, Russia: il complotto del KGB, Bompiani RUSSIA Izzeldin Abuelaish, Non odierò, Piemme PALESTINA Amin Maalouf, I disorientati, Bompiani LIBANO Cingiz Ajtmatov, Occhio di cammello: racconti dalla leggendaria Kirghizia, Besa KIRGHIZISTAN Danilo Manera (a cura di), Vedi Cuba e poi muori: fine secolo all'Avana, Feltrinelli CUBA Shani Boianjiu, La gente come noi non ha paura, Rizzoli ISRAELE Vinicius de Moraes, Per vivere un grande amore, Mondadori BRASILE Laura Boldrini, Solo le montagne non si incontrano mai. Storia di Murayo e dei suoi due padri, Rizzoli SOMALIA Dina Nayeri, Tutto il mare tra di noi, Piemme IRAN Bi Feiyu, I maestri di tuina, Sellerio CINA Virginie Ollagnier, Un posto per ogni cosa, Piemme MAROCCO Will Ferguson, Autostop con Buddha: viaggio attraverso il Giappone, Feltrinelli GIAPPONE Ruth Ozechi, Una storia per l’essere tempo, Ponte alle Grazie GIAPPONE Santiago Gamboa, Preghiere notturne, E/O COLOMBIA Sandra Petrignani, Ultima india, Neri Pozza INDIA Sergio Grea, Saigon addio, Sperling Paperback VIETNAM Tayeb Salih, Le nozze di Al-Zaim, Sellerio SUDAN Conor Grennan, Sette fiori di senape, Piemme NEPAL Preeta Samarasan, Tutto il giorno è sera, Einaudi MALESIA Ryszard Kapu ści ński, Ebano, Feltrinelli AFRICA Ian Holding , Nel mondo insensibiLE, Einaudi ZIMBABWE Naïm Kattan, Addio Babilonia, Manni IRAQ Rafik Schami, La voce della notte, Garzanti SIRIA Yasmina Khadra, Quel che il giorno deve alla notte, Elif Shafak, La casa dei quattro venti , Rizzoli TURCHIA Mondadori ALGERIA Ivan Thays, Un posto chiamato Oreja de Perro, Fawzia Koofi, Lettere alle mie figlie, Fandango PERU Sperling & Kupfer AFGHANISTAN Lucia Vastano, La magnifica felicità imperfetta, Jhumpa Lahiri, La moglie, Guanda INDIA Salani INDIA Consigli di lettura a cura della Biblioteca C. -

Premi Letterari Italiani E Questioni Di Genere

Premi letterari italiani e questioni di genere Loretta Junck Toponomastica femminile Riassunto Si prenderà in esame il numero dei riconoscimenti ottenuti dagli scrittori e dalle scrittrici nei più importanti premi letterari italiani (Strega, Campiello, Viareggio, Bancarella, Bagutta, Calvino) con lo scopo di valutare attraverso un’analisi comparativa sia il gap di genere esistente in questo campo specifico, sia l’evoluzione del fenomeno nel tempo, verificando la presenza delle scrittrici nel canone letterario del Novecento e nelle intitolazioni pubbliche. Obiettivo della ricerca è ottenere un quadro, storico e attuale, della considerazione, da parte della critica letteraria ma non solo, della presenza femminile nel campo della produzione letteraria. Parole chiave: premi letterari, gap di genere, intitolazioni pubbliche. 1 L’idea della ricerca L’idea di una ricerca sui premi letterari italiani è nata in chi scrive dalla lettura di un interessante articolo dell’editore Luigi Spagnol dal titolo “Maschilismo e letteratura. Che cosa ci perdiamo noi uomini”, comparso nell’ottobre del 2016 in illibraio.it. “Il mondo letterario e la società in generale – si chiede l’autore – riconoscono alle opere scritte dalle donne la stessa importanza che viene riconosciuta a quelle scritte dagli uomini? Siamo altrettanto pronti, per esempio, a considerare una scrittrice o uno scrittore dei capiscuola, ad accettare che una donna possa avere la stessa influenza di un uomo sulla storia della letteratura?” La risposta è no, e il numero insignificante di presenze femminili negli albi d’oro dei grandi premi letterari – Nobel, Goncourt, Booker, Strega, Pulitzer – dove le donne sono un quinto degli uomini, non fa che confermare questa intuizione. -

Anti-Semitism on the Silver Screen: Pratolini's Short Story “Vanda”

Anti-Semitism on the Silver Screen: Pratolini’s Short Story “Vanda” and its Cinematic Adaptation(s) “Ora sapevamo. Cominciavamo a pensare.” “Now we knew. We were beginning to think.” (The final voiceover in the short film Roma ’38 [Dir. Sergio Capogna, 1954]) Originally published in 1947, the brief text “Vanda” by Vasco Pratolini, set during the period of the Race Laws in Italy, tells the story of the innocent, tentative romance that blossoms between an unnamed Florentine boy in his late teens and a young girl who hides her Jewish origins from him out of fear.1 This poignant work of prose, which is less than 1200 words in length, aligns Pratolini’s readers with the perspective of the naïf, Christian male protagonist who fails to comprehend the nature of his girlfriend’s struggles as she conceals her Jewish identity. Though he is seemingly obsessed with finding out her secret, a frequent subject in their conversations, the protagonist and narrator is convinced that Vanda’s reticence to introduce him to her father is merely a sign that the man disapproves of their relationship. Pratolini’s text only identifies Vanda’s family as Jewish during the final paragraph of this rather short work. Her death by suicide, motivated by the desperation she experiences as a result of the anti-Semitic Race Laws put in place by Mussolini’s fascist regime in 1938, is dealt with suddenly and concisely by the author in the final clause, in which he simply states that the river had “given back” Vanda’s corpse (Pratolini 30). -

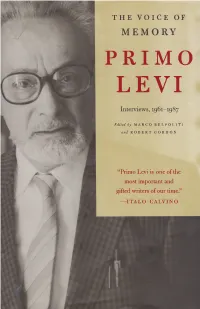

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Valerio Evangelisti Umberto Piersanti, Eugenio Guarini

Le interviste di Progetto Babele Valerio Evangelisti Umberto Piersanti, Eugenio Guarini L’impotenza delle parole nella scrittura di Banana Yoshimoto a cura di Salvatore Ciancitto Anticipazioni di un poeta visionario: Réné Barjavel a cura di V.Madio Lettera da Francoforte di Edith Bruck a cura di Fortuna Dalla Porta Del siciliano a cura di Marco Scalabrino Racconti di: Vittorio Catani, Paolo Durando, Peter Patti, Fabio Monteduro, Carlo Santulli, Fabrizio Ruggeri, Salvo Ferlazzo, Fabrizio Ulivieri, Giuliano Giachino, Giorgio Maggi e... tanti altri! TRADUCENDO TRADUCENDO: La Corrección de los Corderos di Fernando Sorrentino, trad. di Alessando Abate Progetto Babele Quindici EDITORIALE- pb15 a cura di Marco R. Capelli PROGETTO BABELE Un saluto, cordialissimo a tutti i lettori di Progetto Babele. [email protected] Vi sarete già accorti - non è difficile, basta una rapida occhiata all'indice - che questo PB15 è quasi un numero doppio. E, in un certo senso, me ne scuso con i lettori per- chè - è vero! - avevamo promesso di non farlo più. Ma era una promessa difficile da Capo Redattore: Marco R. Capelli mantenere, viste la quantità e la qualità del materiale che ci inviate e, soprattutto, la [email protected] passione con la quale, ancora, ci seguite. Una passione che persino queste cento (e due) pagine faticano a contenere. Coord.gruppo lettura: Claudio Palmieri Centodue pagine, dicevamo, di racconti, articoli e recensioni. Soprattutto recensioni. [email protected] Le recensioni di PB, cioè le recensioni dei libri che, confidando nel nostro giudizio, ci avete mandato in lettura. Diciotto recensioni, diciotto voci nuove (si può ancora dire Coord.gruppo recensione: Carlo Santulli "alternative"?) nel panorama letterario italiano, altrettante piacevoli sorprese. -

To Be Or Not to Be a Mother: Choice, Refusal, Reluctance and Conflict

intervalla: Special Vol. 1, 2016 ISSN: 2296-3413 To Be or Not to Be a Mother: Choice, Refusal, Reluctance and Conflict. Motherhood and Female Identity in Italian Literature and Culture Essere o non essere madre: Scelta, rifiuto, avversione e conflitto. Maternità e identità femminile nella letteratura e cultura italiane Laura Lazzari AAUW International Postdoctoral Fellow, Georgetown University Affiliated Research Faculty, Franklin University Switzerland Joy Charnley Independent Researcher, Glasgow ABSTRACT This volume of intervalla centres on the themes of choice and conflict, refusal and rejection, and analyses how mothers and non-mothers are perceived in Italian society. The nine essays cover a variety of genres (novel, auto-fiction, theatre) and predominantly address how these perceptions are translated into literary form, ranging from the 1940s to the early twenty-first century. They study topics such as the ambivalent feelings and difficult experiences associated with motherhood (doubt, post-natal depression, infanticide, IVF), the impact of motherhood and non-motherhood on female identity, attitudes towards childless/childfree women, the stereotype of the “good mother,” and the ways in which such stereotypes are rejected, challenged or subverted. Major Italian writers, such as Lalla Romano, Paola Masino, Oriana Fallaci, Laudomia Bonanni and Elena Ferrante, are included in these analyses, alongside contemporary “momoirs” and works by Valeria Parrella, Lisa Corva, Eleonora Mazzoni, Cristina Comencini and Grazia Verasani. KEY WORDS: motherhood, Italian literature, Italian culture, female identity, women’s writing PAROLE CHIAVE: maternità, letteratura italiana, cultura italiana, identità femminile, scrittura delle donne Copyright © 2016 (Lazzari & Charnley). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC by-nc-nd 4.0). -

Internet STESO

Il Comune di Rapallo indice la trentaseiesima edizione del Premio letterario nazionale per la donna scrittrice - Rapallo 2020, finalizzato a incoraggiare e valorizzare l’attività letteraria femminile. ALBO D’ORO La partecipazione al Premio è riservata alle opere edite di narrativa di scrittrici PRIMA EDIZIONE 1985 DICIANNOVESIMA EDIZIONE 2003 in lingua italiana, pubblicate per la prima volta a partire dal 1º marzo 2019. Virginia Galante Garrone Francesca Marciano «L’ora del tempo» Garzanti «Casa Rossa» Longanesi - - GENOVA Le autrici o i loro editori, entro il 6 aprile 2020, dovranno far pervenire dodici SECONDA EDIZIONE 1986 VENTESIMA EDIZIONE 2004 copie dell’opera che intendono presentare alla segreteria del Premio, presso Giuliana Berlinguer Francesca Duranti CREATTIVA Comune, Ufficio Cultura, piazza Molfino nº 10, 2º piano, 16035 Rapallo (Ge- «Una per sei» Camunia «L’ultimo viaggio della Canaria» © nova). L’Ufficio Cultura è aperto dal lunedì al venerdì, dalle ore 9 alle ore 13. TERZA EDIZIONE 1987 Marsilio Sul plico dovrà essere indicata la dicitura “Premio Letterario Nazionale per Gina Lagorio VENTUNESIMA EDIZIONE 2005 la Donna Scrittrice - Rapallo 2020”. L’inosservanza di tali modalità sarà mo- «Golfo del paradiso» Garzanti Patrizia Bisi tivo di esclusione dal concorso. QUARTA EDIZIONE 1988 «Daimon» Einaudi BANDO Entro il 31 maggio 2020 una giuria di critici e letterati formata da Elvio Gua- Rosetta Loy VENTIDUESIMA EDIZIONE 2006 gnini (presidente), Maria Pia Ammirati, Mario Baudino, Francesco De Nicola, «Le strade di polvere» Einaudi Silvia Ballestra DI CONCORSO Chiara Gamberale, Luigi Mascheroni, Ermanno Paccagnini, Mirella Serri, Pier QUINTA EDIZIONE 1989 «La seconda Dora» Rizzoli Antonio Zannoni, (segretario-coordinatore, responsabile del Premio), sce- Edith Bruck VENTITREESIMA EDIZIONE 2007 glierà con giudizio inappellabile e definitivo una terna di opere. -

Nella Casa Dei Libri. 7 La Storia Raccontata

Nella Casa dei libri. 7 La storia raccontata: il vero e il verosimile del narratore Il ‘900: proposte di lettura Emigrazione Ulderico Bernardi, A catàr fortuna: storie venete, d’Australia e del Brasile, Vicenza, Neri e Pozza, 1994 Cesare Bermani, Al lavoro nella Germania di Hitler, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 1998 Piero Brunello, Pionieri. Gli italiani in Brasile e il mito della frontiera, Roma, Donzelli, 1994 Piero Brunello, Emigranti, in Storia d’Italia. Le regioni dall’unità ad oggi. Il Veneto, Torino, Einaudi, 1984 Savona - Straniero (a cura di), Canti dell’emigrazione, Milano, Garzanti, 1976 Emilio Franzina, Merica! Merica!, Verona, Cierre, 1994 Emilio Franzina, Dall’Arcadia in America, Torino, Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli, 1994 Paolo Cresci e Luciano Guidobaldi (a cura di), Partono i bastimenti, Milano, Mondadori, 1980 Elio Vittorini, Conversazione in Sicilia, Milano, Mondadori, 1980 Prima guerra mondiale Carlo Emilio Gadda, Giornale di guerra e di prigionia, Milano, Garzanti,1999 Emilio Lussu, Un anno sull’Altopiano, Torino, Einaudi, 1945 Paolo Monelli, Le scarpe al sole, Vicenza, Neri Pozza, 1994 Renato Serra, Lettere in pace e in guerra, Torino, Aragno, 2000 Mario Rigoni Stern, Storia di Tonle, Torino, Einaudi, 1978 Mario Rigoni Stern, L’anno della vittoria, Torino, Einaudi, 1985 Mario Rigoni Stern, Ritorno sul Don, Torino, Einaudi, 1973 Primo dopoguerra Corrado Alvaro, Gente in Aspromonte, Milano, Garzanti, 1970 Romano Bilenchi, Il capofabbrica, Milano, Rizzoli, 1991 Carlo Levi, Cristo si è fermato a Eboli, Torino, Einaudi, 1945 Mario Rigoni Stern, Le stagioni di Giacomo, Torino, Einaudi, 1995 Fascismo Vitaliano Brancati, Il bell’Antonio, Milano, Bompiani, 2001 Giorgio Boatti, Preferirei di no, Torino, Einaudi, 2001 Carlo Cassola, La casa di via Valadier, Milano, Rizzoli, 2001 Alba de Céspedes, Nessuno torna indietro, Milano, 1966 Vittorio Foa, Lettere della giovinezza. -

Sulla Collina Delle Muse. Gian Domenico Giagni E Sinisgalli 15

Edisud Salerno Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook, New York NUOVI PARADIGMI Collezione di Studi e Testi oltre i confini Diretta da Sebastiano Martelli Mario B. Mignone Franco Vitelli I volumi della Collezione sono sottoposti al preliminare vaglio scientifico di un comitato di referee anonimi Edisud Salerno Via Leopoldo Cassese, 26 Tel. e fax: 089 220899 84122 Salerno - Italia e-mail: [email protected] http://www.edisud.it IL SISTEMA DI QUALITÀ DELLA CASA EDITRICE È CERTIFICATO ISO 9001:2008 Forum Italicum Publishing Center for Italian Studies State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, N Y 11794-3358 - USA e-mail: [email protected] http://www.italianstudies.org Pubblicazione realizzata con un contributo della Regione Basilicata e dell’Università degli Studi “Aldo Moro” di Bari Edisud Salerno Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook New York Il guscio della chiocciola Studi su Leonardo Sinisgalli a cura di Sebastiano Martelli e Franco Vitelli con la collaborazione di Giulia Dell’Aquila e Laura Pesola 2° Nuovi Paradigmi 6 Collezione di studi e testi oltre i confini © 2012 Edisud Salerno ISBN 978-88-95154-90-9 © Forum Italicum Publishing Stony Brook, New York Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Il guscio della chiocciola. Studi su Leonardo Sinisgalli, a cura di Sebastiano Martelli e Franco Vitelli con la collaborazione di Giulia Dell’Aquila e Laura Pesola ISBN 1-893127-92-3 428 p. 27 cm.— 1. Leonardo Sinisgalli; 2. Italian Literature; 3. Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, Arts and Science; 4. Criticism and Interpretation I. Title II. Series L’editore è a disposizione di eventuali aventi diritto che non è riuscito a contattare Progetto di ingegneria del libro a geometria variabile di Mimmo Castellano Ricerca iconografica e impaginazione di Palmarosa Fuccella Indice del volume 2° Itinerario di un poeta 6 p. -

Uno Sguardo Sulla Letteratura Italiana Contemporanea

Paulina Matusz Università di Breslavia Uno sguardo sulla letteratura italiana contemporanea Literatura włoska w toku 2, a cura di Hanna Serkowska, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2011, 298 pp. Quando nel 2006 uscì in Polonia il volume Literatura włoska w toku (Let- teratura italiana in corso), si diceva che fosse una monografia speciale, una vera e propria rarità. I critici e recensori del libro sottolineavano che mai prima d’allora la letteratura italiana contemporanea fosse presentata al pubblico letterario polacco in maniera così dettagliata e ponderata. Si trattava infatti di un’interessante raccolta di articoli e saggi, scritti con l’ambizione di mostrare e descrivere il panorama letterario italiano nel modo più ampio possibile, presentando così i testi degli scrittori con- temporanei italiani anche ai lettori polacchi che fino allora solo sporadi- camente avevano avuto l’occasione di conoscere i libri più recenti degli autori provenienti dalla penisola italica . “Il fattore più importante che ha fatto nascere questa raccolta è stata la convinzione che della letteratura italiana in Polonia se ne scrive sem- pre troppo poco e troppo raramente”1 scriveva nell’introduzione al libro la curatrice del volume, professoressa Hanna Serkowska, giustifican- 1 H. Serkowska, Wprowadzenie, [in:] Literatura włoska w toku. O wybranych współczesnych pisarzach Italii, a cura di H. Serkowska, Zakład Narodowy im. Osso- lińskich, Wrocław 2006, p. 5. 164 Paulina Matusz do e spiegando così in qualche modo l’idea che aveva spinto l’intero gruppo di autori a scrivere e a raccogliere i loro testi in un unico libro. Sempre nella stessa introduzione era stato annunciato anche il volume successivo che avrebbe dovuto di lì a poco continuare l’opera di divul- gazione della moderna letteratura italiana in Polonia – che però è uscito solo alla fine del 2011, quindi ben cinque anni dopo la pubblicazione del primo libro. -

Dimensioni Sommario Rubriche In

INDICE CRONOLOGICO DEI SOMMARI a. I - 1957, 1 giugno, n. 1 La Redazione, Quasi un’introduzione, p. 3 Auguri per Dimensioni, p. 5: Gioacchino Volpe, p. 5 Ettore Paratore, p. 5 Giovanni Titta Rosa, p. 6 Laudomia Bonanni, p. 6 Mario Pomilio, p. 6 Laudomia Bonanni, Terremoto [racconto], p. 7 Fausto Brindesi, La crisi di un’epoca – 1. Monografie Sallustiane, p. 14 Ottaviano Giannangeli, Oltrecielo e oltre tempo: parole nuove in Montale, p. 19 Alfredo Postiglione, Tre streghe, dal Dizionario illustrato degli Incisori italiani [illustrazione], p. 24 Taverna delle Muse, p. 25 Giovanni Titta Rosa: Festa in Trastevere [poesia], p. 25 Forse questo ti giova [poesia], p. 26 Le Arti, p. 28 Pasquale Scarpitti, Remo Brindisi, p. 28 Giornale intimo [nota], p. 30 Giuseppe Bolino, Meditazione sulla cultura, p. 30 Ricordo di Maestri, p. 33: Ottaviano Giannangeli, Giuseppe De Robertis, p. 33 Giammario Sgattoni, Francesco Flora, p. 35 Biblioteca, p. 39 Giuseppe Sorge: Domenico Ciampoli romanziere, p. 39 o. g. [Ottaviano Giannangeli], Giammario Sgattoni: Poesie, p. 39 Giuseppe Rosato, Francesco Paolo Giancristofaro: Cesare De Titta nella poesia dialettale abruzzese, p. 40 a. I - 1957, luglio-agosto, n. 2-3 Mario Pomilio, Zia Clara [racconto], p. 3 Glauco Curci, I due volti dell’energia atomica. Il nostro tempo, p. 7 David Gazzani, L’incredibile Abruzzo. Urbanistica, p. 13 Ettore Paratore, Uno strano atteggiamento della cultura abruzzese, p. 25 Fausto Brindesi, La crisi di un’epoca – 2. Monografie Sallustiane, p. 36 Luigi Illuminati, Ovidio autobiografico e didascalico. Il bimillenario, p. 41 Ottaviano Giannangeli, Un amico del Petrarca [lettere a Barbato di Sulmona], p.