Música Indígena En Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vitality of Damana, the Language of the Wiwa Indigenous Community

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-24-2020 3:00 PM Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce, The University of Western Ontario : Trillos Amaya, Maria, Universidad del Atlantico A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Hispanic Studies © Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fernandez Fernandez, Tatiana L., "Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7134. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7134 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa People The Wiwa are Indigenous1 people who live in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia. This project examines the vitality of Damana [ISO 693-3: mbp], their language, in two communities that offer high school education in Damana and Spanish. Its aim is to measure the level of endangerment of Damana according to the factors used in the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through a questionnaire that gathered demographic and background language information, self-reported proficiency and use of Spanish and Damana [n=56]. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 24 February 2004 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH/SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Item 6 of the provisional agenda RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION Report by Mr. Doudou Diène, Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Addendum MISSION TO COLOMBIA* ** * The summary of this report is being circulated in all official languages. The report itself is contained in the annex to this document and is being circulated in English, French and Spanish. ** This document is submitted late so as to include the most up-to-date information possible. GE.04-11140 (E) 150304 170304 E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 page 2 Summary In accordance with his mandate, the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance visited Colombia from 27 September to 11 October 2003 at the invitation of the Colombian Government. The visit made it possible to evaluate the progress achieved in the implementation of policies and measures to improve the situation of Afro-Colombians and indigenous populations, particularly following the visit of the former Special Rapporteur, Mr. Maurice Glèlè-Ahanhanzo, in 1996 (see E/CN.4/1997/71/Add.1, paras. 66-68). The Special Rapporteur also examined the situation of the Roma, a people that has apparently been excluded from Colombian ethno-demographic data. The Roma, who receive very little attention from human rights defenders, consider themselves to be victims of age-old discrimination. -

LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION of the COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL Offensive Sharpens

Reviews BuenaventuraBuenaventura LiberationLiberation more.. and footballfootball massacremassacre ofof MotherMother EarthEarth 12 dead and still no justice Indigenous peoples and We speak to the mothers of the battle of Cauca Valley Colombia’s lost sons page 19 . page 13 FRONTLINE LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION OF THE COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL offensive sharpens Edgar Paez in Colombia series of attacks against the very existence of SINALTRAINAL have occurred in different Aregions of Colombia; ranging from a raid on the unionʼs national headquarters in Bogotá, to the assassination of one of our activists. These incidents are an example of President Álvaro Uribe Vélezʼs policy of ʻdemocratic securityʼ and take place at a diffi cult moment due to labour confl icts with the transnationals Nestlé and Coca-cola. These are some of the violent incidents against the lives and security of our members: Raid on union headquarters At approximately 12:15 a.m. on 3 August 2006, uniformed men who identifi ed themselves as members of SIJIN, the Judicial Police, entered into the headquarters of SINALTRAINAL located at No 35 – 18, 15th Avenue in Bogotá city and proceeded to search the union building stating it was a preventative operation for the upcoming 7 August, the inauguration day of president Álvaro Uribe Vélez. Police or thieves? US soldiers are deployed on every continent to defend Washington’s fi nancial interests Jacob Bailey That morning SIJIN agents were seen fi lming the outside of the unionʼs headquarters. This raid was carried out without a judicial order, being classifi ed curiously as an “act of voluntary registration”. -

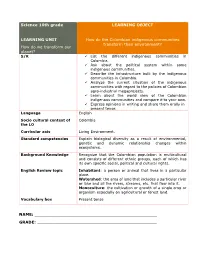

Science 10Th Grade LEARNING OBJECT

Science 10th grade LEARNING OBJECT LEARNING UNIT How do the Colombian indigenous communities transform their environment? How do we transform our planet? S/K List the different indigenous communities in Colombia. Ask about the political system within some indigenous communities. Describe the infrastructure built by the indigenous communities in Colombia. Analyze the current situation of the indigenous communities with regard to the policies of Colombian agro-industrial megaprojects. Learn about the world view of the Colombian indigenous communities and compare it to your own. Express opinions in writing and share them orally in present tense. Language English Socio cultural context of Colombia the LO Curricular axis Living Environment. Standard competencies Explain biological diversity as a result of environmental, genetic and dynamic relationship changes within ecosystems. Background Knowledge Recognize that the Colombian population is multicultural and consists of different ethnic groups, each of which has its own specific social, political and cultural rights. English Review topic Inhabitant: a person or animal that lives in a particular place. Watershed: the area of land that includes a particular river or lake and all the rivers, streams, etc. that flow into it. Monoculture: the cultivation or growth of a single crop or organism especially on agricultural or forest land. Vocabulary box Present tense NAME: _________________________________________________ GRADE: ________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Read the following dialog Indigenous child: Did you know that we humans come from the knee of the god Gútapa? White child: From the knee of God Gútapa? Indigenous child: Yes, one day Gútapa was taking a bath in the creek, and some wasps stung her in her knees, they swelled up and from there emerged Ipi and Yoi. -

Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Santiago, 2021 FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest governance by indigenous and or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. tribal peoples. An opportunity for climate action in Latin If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under America and the Caribbean. Santiago. FAO. the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If a https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en translation of this work is created, it must include the following disclaimer along with the required citation: The designations employed and the presentation of “This translation was not created by the Food and material in this information product do not imply the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United this translation. The original English edition shall be the Nations (FAO) or Fund for the Development of the authoritative edition.” Indigenous Peoples of Latina America and the Caribbean (FILAC) concerning the legal or development status of Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or licence shall be conducted in accordance with the concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on The mention of specific companies or products of International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) as at present in force. -

Herederos Del Jaguar Y La Anaconda

HEREDEROS DEL JAGUAR Y LA ANACONDA NINA S. DE FRIEDEMANN Y JAIME AROCHA antropología HEREDEROS DEL JAGUAR Y LA ANACONDA NINA S. DE FRIEDEMANN Y JAIME AROCHA antropología Catalogación en la publicación – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia Sánchez de Friedemann, Nina, 1935-1998, autor Arocha Rodríguez, Jaime, 1945-, autor Herederos del jaguar y la anaconda / Nina S. de Friedemann y Jaime Arocha ; presentación, Carlos Guillermo Páramo Bonilla. – Bogotá : Ministerio de Cultura : Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2016. 1 recurso en línea : archivo de texto PDF (560 páginas). – (Biblioteca Básica de Cultura Colombiana. Antropología / Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia) Incluye glosario e índice onomástico. -- Referencias bibliográficas al final de cada ensayo. ISBN 978-958-8959-52-8 1. Etnología – Historia – Colombia 2. Antropología – Historia - Colombia 3. Culturas indígenas - Colombia 4. Indígenas de Colombia - Vida social y costumbres 5. Libro digital I. Páramo Bonilla, Carlos Guillermo, autor de introducción II. Título III. Serie CDD: 305.8009861 ed. 23 CO-BoBN– a994091 Mariana Garcés Córdoba MINISTRA DE CULTURA Zulia Mena García VICEMINISTRA DE CULTURA Enzo Rafael Ariza Ayala SECRETARIO GENERAL Consuelo Gaitán DIRECTORA DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL Javier Beltrán José Antonio Carbonell COORDINADOR GENERAL Mario Jursich Julio Paredes Jesús Goyeneche COMITÉ EDITORIAL ASISTENTE EDITORIAL Y DE INVESTIGACIÓN Taller de Edición • Rocca® REVISIÓN Y CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS, DISEÑO EDITORIAL Y DIAGRAMACIÓN eLibros CONVERSIÓN DIGITAL PixelClub S. A. S. ADAPTACIÓN DIGITAL HTML Adán Farías CONCEPTO Y DISEÑO GRÁFICO Con el apoyo de: BibloAmigos ISBN: 978-958-8959-52-8 Bogotá D. C., diciembre de 2016 © Jaime Arocha Rodríguez © 1989, Carlos Valencia Editores © 2016, De esta edición: Ministerio de Cultura – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia © Presentación: Carlos Guillermo Páramo Bonilla Material digital de acceso y descarga gratuitos con fines didácticos y culturales, principalmente dirigido a los usuarios de la Red Nacional de Bibliotecas Públicas de Colombia. -

Afro-Colombian Women's Organisations in Post-Accord Colombia

1 | A LTERNAUTAS 7 (1) – J ULY 2020 Alternautas (Re)Searching Development: The Abya Yala Chapter Alternautas – Vol.7 – Issue 1 – July 2020 Preface Introduction to the Special Issue on Indigenous and Afrodescendant Movements and Organizations in Latin America: Negotiating, Resisting, Performing and Re-purposing Dominant Categories – Diego Silva & Nancy Postero Afro-Colombian Women’s Organisations in Post- Accord Colombia: Gendering and Racialising Violent Pluralism across the Conflict Continuum in Bogotá, Colombia – Julia Zulver Spatiality, Temporality and Ontology: Constraints for the Restitution of Indigenous Peoples’ Territorial Rights in Colombia – Yira Lazala Were there Nonhumans in Bagua? The Gobierno Territorial Autónomo de la Nación Wampis and the Emergence of Vertical Territoriality in the Northern Peruvian Amazon – Thomas Niederberger Baianas de Acarajé against FIFA: Coloniality Nowadays – Larissa Da Silva Araujo Occupying and Expanding (un)Expected Categories: Ways of Being and Becoming Indigenous within the United Nations System– Urpi Saco Chung Seeds of Resistance: The Pijao Group, a Youth Process of Decolonization and the Unity of the Pijao People– Viviana Lozano Ducuara, Edwin Alexander Henao Conde ISSN - 2057-4924 -- Alternautas is a peer reviewed academic blog EDITORIAL BOARD that publishes content related to Latin American Ana Estefanía Carballo (University of Melbourne, Australia) Critical Development Michela Coletta (University of Warwick, United Kingdom) thinking. Gibrán Cruz-Martínez (Institute of Public Goods and -

Pueblos Indígenas De Colombia Compilación Por Jacobo Elí Izquierdo

Pueblos Indígenas de Colombia Compilación por Jacobo Elí Izquierdo PDF generado usando el kit de herramientas de fuente abierta mwlib. Ver http://code.pediapress.com/ para mayor información. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Feb 2010 20:35:28 UTC Contenidos Artículos Introducción 1 Población indígena de Colombia 1 A-B 6 Achagua 6 Andakí 7 Andoque 9 Arhuaco 12 Awá 16 Bara (indígenas) 18 Barasana 19 Barí 21 Bora (pueblo) 23 C-D 24 Camsá 24 Carijona 26 Catíos 27 Chamíes 29 Chimila 30 Cocama 32 Cocamilla 33 Cofán 33 Coreguaje 35 Coyaimas 36 Cubeo 40 Cuiba 42 Desano 44 E-G 47 Emberá 47 Guahibo 49 Guanano 52 Guanes 53 Guayabero 55 Guayupe 58 H-K 61 Hitnü 61 Indios achaguas 62 Inga 62 Jupda 64 Kankuamos 68 Karapana 69 Kogui 70 Kuna (etnia) 72 Kurripako 77 L-Q 79 Macuna 79 Mirañas 81 Misak 82 Mocaná 83 Muiscas 84 Nasa 96 Nukak 99 Pastos 104 Pijao 105 Piratapuyo 116 Pueblo Yanacona 117 Puinave 118 R-T 119 Raizal 119 Siona 123 Siriano 124 Sáliba 125 Tanimuca 126 Tatuyo 127 Tikuna 128 Tucano 131 Tupe 133 Tuyuca 134 U-Z 135 U'wa 135 Uitoto 136 Umbrá 138 Wayúu 138 Wenaiwika 143 Wiwa 145 Wounaan 147 Yagua (indígenas) 148 Yariguies 150 Yucuna 151 Yukpa 153 Yuri (etnia) 154 Zenú 155 Conceptos generales de apoyo 158 Resguardo indígena 158 Territorios indígenas 159 Amerindio 159 Referencias Fuentes y contribuyentes del artículo 169 Fuentes de imagen, Licencias y contribuyentes 171 Licencias de artículos Licencia 173 1 Introducción Población indígena de Colombia Según las fuentes oficiales,[1] la población indígena o amerindia en Colombia, en los inicios del siglo XXI, es de 1'378.884, lo cual quiere decir que los indígenas son el 3,4% de la población del país. -

Quoted, 264 Adelman, Je

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13328-9 - Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective James Mahoney Index More information Index Abad people, 106 to Canada, 251; and contrasting Abernethy, David B., 2 levels of development in interior vs. Aborigines, 236 littoral, 132; and estancias, 127–8, Acemoglu, Daron, 13–14, 17–19, 234, 146; European migration to, 131, 264–5; quoted, 264 211; and exploitation of indigenous Adelman, Jeremy, 204; quoted, 203 population, 81; exports of, 128; Africa: British colonialism in, 236–7; financial institutions in, 126;and economic and social disaster in, 237, “free trade,” 125–6; gaucho workers 257; precolonial societies, 256 in, 127; GDP per capita of, 128, African population: as cause of liberal 210–12; “golden age” in, 128, 210, colonialism, 183, 201; in colonial 211; intendant system in, 126; Argentina, 125–6, 130; in colonial investments in education in, 224;lack Brazil, 245–6; in colonial Colombia, of dominance of large estates in, 127; 107–8, 160; in colonial El Salvador, landed class of, 127; literacy and life 95; colonial exploitation of, 53;in expectancy in, 222–4; livestock colonial Mexico, 58, 60; in colonial industry of, 82, 126–7, 130, 211; Peru, 67–9, 71; in colonial Uruguay, merchants in, 82, 126–8; 80; in United States, 236;inWest nation-building myths in, 224; Indies, precolonial societies in, 77–9; 238; see also slavery problems of industrialization in, 211, Alvarado, Pedro de, 94, 97 212; reversal of development in, 212; Amaral, Samuel, quoted, -

260317 Chaves Agudelo Final Thesis

(RE) MEANINGS OF NATURE IN A NEOLIBERAL GLOBALIZED MODERN WORLD: THREE CASES OF COLOMBIAN INDIGENOUS ETHNICITIES (PIJAO, COFAN AND MUISCA- CHIBCHA) Judy Marcela Chaves Agudelo ORCID Identifier: 0000-0003-1915-626X Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 School of Geography Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree 1 “Judge your success by what you had to give up, in order to achieve it” Author unknown Family, friends, food, sunlight… Colombia 2 Ñutse jpa afachuma Welcome to this reading (Cofán language) Quyca chibcha muyqyui guamox, suna cho bohoza asgue quycan We are inhabitants of valleys and mountains, good paths in our territories [through this reading] (Muisca languange) Lumax emex eramex lumax kunkix ojamax arax ueños angolax kex lumbix guazabarax nasex We brothers and sisters, based on our fraternity, must listen to our grandparents’ wise words, grandparents of our warrior origins as the house of our ancestors, of Mother Earth (Pijao language) 3 ABSTRACT This thesis analyses to what extent, and how, discourses of ‘nature’ held by three Colombian ethnicities have hybridized with those of a growing national adoption of neoliberal, globalized modern foundations. ‘Neo-liberalization’, ‘globalization’ and ‘modernization’ affect all fields of Colombian reality, and have been materialized in indigenous territories. Indigenous struggles are fighting and 'contesting’ modernity. I demonstrate that modernity and globalization, being ongoing processes, have impacted indigenous realities since the XVI century, and that the neo- liberalization of the Colombian economy during the 1990s implied a deeper penetration in indigenous localities. These political transitions, and the Colombian embrace of multiculturalism, have synergistically permeated indigenous social realities. -

Sonia Chager Navarro

Ph.D. DISSERTATION Ph.D. PROGRAM IN DEMOGRAPHY Sonia Chager Navarro Supervisors: Dr. Albert Esteve Palós and Dr. Joaquín Recaño Valverde Centre d'Estudis Demogràfics / Departament de Geografia Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Source Cover Photo: GOSIPPME BLOG (January 22, 2014) : 'My Life Was Ruined': Ethiopian Child Bride, Forced Into Marriage At 10, Pregnant At 13 And Widowed By 14, Tells Her Story" , Picture above "Global problem: India is the country with the highest number of child brides, this little girl among them"; accessed on date September 20, 2014 at 'http://www.gosippme.com/2014/01/my-life-was-ruined-ethiopian-child.html' Ph.D. DISSERTATION Ph.D. PROGRAM IN DEMOGRAPHY Centre d'Estudis Demogràfics / Departament de Geografia Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Tying the Knot and Kissing Childhood Goodbye? Early Marriage in Educationally Expanding Societies Sonia Chager Navarro Supervisors: Dr. Albert Esteve Palós Dr. Joaquín Recaño Valverde September 2014 | 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS La realización de esta tesis no hubiera sido posible en primer lugar sin la ayuda, guía, cariño y apoyo incondicional que he recibido de personas muy especiales para mí a lo largo de estos años. Además, la culminación de este trabajo de investigación doctoral se ha hecho realidad gracias al soporte institucional de la Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, de su Departamento de Geografía, y particularmente del Centre d'Estudis Demogràfics y a su directora, la Dra. Anna Cabré, quién depositó en esta doctoranda su confianza y acompañamiento, permitiendo que llevara a término esta tesis, que además de enriquecerme en el terreno profesional lo ha hecho también, si cabe más, en el personal. -

English) Is Proposed, Which Enables Potential Risks and Social and Environmental Conflicts to Be Minimized While Promoting the Benefits of REDD+

R-PP Submission Format v. 5 Revised (December 22, 2010): Working Draft for Use by Countries. (Replaces R-PP v.4, January 28, 2010; and draft v. 5, Oct. 30, 2010). Republic of Colombia NOTE ON THIS VERSION OF THE FORMAL SUBMISSION OF THE READINESS PREPARATION PROPOSAL FOR REDD + (R-PP) (Version 4.0 – September 27, 2011) The Government of Colombia, as part of the preparation regarding the possibility of carrying out Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) activities, has developed a proposal for readiness for REDD+ (R-PP) within the framework of support received by the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). In this context, we present this fourth version of the document R-PP to be officially submitted as a formal document at the tenth meeting of the FCPF Participants Committee to be held in Berlin, Germany, from October 17 to 19, 2011. This version includes the contributions and adjustments made to previous versions and is the work and collaboration among different stakeholders in the country, including the communities who live directly in the forests, the productive sectors, the state institutions and representatives of civil society. Even included are the PC and TAP reviewers of the FCPF who evaluated the previous versions. While this document is formally submitted for evaluation by the FCPF, we are still inviting interested parties to continue working together with the R-PP development team ([email protected]) to improve this proposal by involving current and future strategic allies to accompany and monitor the proper implementation of resources obtained to strengthen the development of REDD+ activities in the country, within the framework of respect for the rights of communities, the conservation of natural ecosystems, and the effectiveness in the maintenance of carbon stocks in the country.