Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vitality of Damana, the Language of the Wiwa Indigenous Community

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-24-2020 3:00 PM Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce, The University of Western Ontario : Trillos Amaya, Maria, Universidad del Atlantico A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Hispanic Studies © Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fernandez Fernandez, Tatiana L., "Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7134. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7134 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa People The Wiwa are Indigenous1 people who live in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia. This project examines the vitality of Damana [ISO 693-3: mbp], their language, in two communities that offer high school education in Damana and Spanish. Its aim is to measure the level of endangerment of Damana according to the factors used in the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through a questionnaire that gathered demographic and background language information, self-reported proficiency and use of Spanish and Damana [n=56]. -

Chanting in Amazonian Vegetalismo

________________________________________________________________www.neip.info Amazonian Vegetalismo: A study of the healing power of chants in Tarapoto, Peru. François DEMANGE Student Number: 0019893 M.A in Social Sciences by Independent Studies University of East London, 2000-2002. “The plant comes and talks to you, it teaches you to sing” Don Solón T. Master vegetalista 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter one : Research Setting …………………………….…………….………………. 3 Chapter two : Shamanic chanting in the anthropological literature…..……17 Chapter three : Learning to communicate ………………………………………………. 38 Chapter four : Chanting ……………………………………..…………………………………. 58 Chapter five : Awakening ………………………………………………………….………… 77 Bibliography ........................................................................................... 89 Appendix 1 : List of Key Questions Appendix 2 : Diary 3 Chapter one : Research Setting 1. Panorama: This is a study of chanting as performed by a new type of healing shamans born from the mixing of Amazonian and Western practices in Peru. These new healers originate from various extractions, indigenous Amazonians, mestizos of mixed race, and foreigners, principally Europeans and North-Americans. They are known as vegetalistas and their practice is called vegetalismo due to the place they attribute to plants - or vegetal - in the working of human consciousness and healing rituals. The research for this study was conducted in the Tarapoto region, in the Peruvian highland tropical forest. It is based both on first hand information collected during a year of fieldwork and on my personal experience as a patient and as a trainee practitioner in vegetalismo during the last six years. The key idea to be discussed in this study revolves around the vegetalista understanding that the taking of plants generates a process of learning to communicate with spirits and to awaken one’s consciousness to a broader reality - both within the self and towards the outer world. -

Turtle Shells in Traditional Latin American Music.Cdr

Edgardo Civallero Turtle shells in traditional Latin American music wayrachaki editora Edgardo Civallero Turtle shells in traditional Latin American music 2° ed. rev. Wayrachaki editora Bogota - 2021 Civallero, Edgardo Turtle shells in traditional Latin American music / Edgardo Civallero. – 2° ed. rev. – Bogota : Wayrachaki editora, 2021, c2017. 30 p. : ill.. 1. Music. 2. Idiophones. 3. Shells. 4. Turtle. 5. Ayotl. 6. Aak. I. Civallero, Edgardo. II. Title. © 1° ed. Edgardo Civallero, Madrid, 2017 © of this digital edition, Edgardo Civallero, Bogota, 2021 Design of cover and inner pages: Edgardo Civallero This book is distributed under a Creative Commons license Attribution- NonCommercial-NonDerivatives 4.0 International. To see a copy of this license, please visit: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Cover image: Turtle shell idiophone from the Parapetí River (Bolivia). www.kringla.nu/. Introduction Turtle shells have long been used all around the world for building different types of musical instruments: from the gbóló gbóló of the Vai people in Liberia to the kanhi of the Châm people in Indochina, the rattles of the Hopi people in the USA and the drums of the Dan people in Ivory Coast. South and Central America have not been an exception: used especially as idiophones ―but also as components of certain membranophones and aero- phones―, the shells, obtained from different species of turtles and tortoises, have been part of the indigenous music since ancient times; in fact, archaeological evi- dence indicate their use among the Mexica, the different Maya-speaking societies and other peoples of Classical Mesoamerica. After the European invasion and con- quest of America and the introduction of new cultural patterns, shells were also used as the sound box of some Izikowitz (1934) theorized that Latin American string instruments. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 24 February 2004 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH/SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Item 6 of the provisional agenda RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION Report by Mr. Doudou Diène, Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Addendum MISSION TO COLOMBIA* ** * The summary of this report is being circulated in all official languages. The report itself is contained in the annex to this document and is being circulated in English, French and Spanish. ** This document is submitted late so as to include the most up-to-date information possible. GE.04-11140 (E) 150304 170304 E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 page 2 Summary In accordance with his mandate, the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance visited Colombia from 27 September to 11 October 2003 at the invitation of the Colombian Government. The visit made it possible to evaluate the progress achieved in the implementation of policies and measures to improve the situation of Afro-Colombians and indigenous populations, particularly following the visit of the former Special Rapporteur, Mr. Maurice Glèlè-Ahanhanzo, in 1996 (see E/CN.4/1997/71/Add.1, paras. 66-68). The Special Rapporteur also examined the situation of the Roma, a people that has apparently been excluded from Colombian ethno-demographic data. The Roma, who receive very little attention from human rights defenders, consider themselves to be victims of age-old discrimination. -

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

1407234* A/HRC/27/52/Add.1

United Nations A/HRC/27/52/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 July 2014 English Original: Spanish Human Rights Council Twenty-seventh session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya Addendum The status of indigenous peoples’ rights in Panama* Summary This report examines the human rights situation of indigenous peoples in Panama on the basis of information gathered by the Special Rapporteur during his visit to the country from 19 to 26 July 2013 and independent research. Panama has an advanced legal framework for the promotion of the rights of indigenous peoples. In particular, the system of indigenous regions (comarcas) provides considerable protection for indigenous rights, especially in terms of land and territory, participation and self-governance, and health and education. National laws and programmes on indigenous affairs provide a vital foundation on which to continue building upon and strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama. However, the Special Rapporteur notes that this foundation is fragile and unstable in many regards. As discussed in this report, there are a number of problems with regard to the enforcement and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama, particularly with regard to their right to their lands and natural resources, the implementation of large- scale investment projects, self-governance, participation and their economic and social rights, including the rights to economic development, education and health. In the light of the findings set out in this report, the Special Rapporteur makes specific recommendations to the Government of Panama. -

LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION of the COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL Offensive Sharpens

Reviews BuenaventuraBuenaventura LiberationLiberation more.. and footballfootball massacremassacre ofof MotherMother EarthEarth 12 dead and still no justice Indigenous peoples and We speak to the mothers of the battle of Cauca Valley Colombia’s lost sons page 19 . page 13 FRONTLINE LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION OF THE COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL offensive sharpens Edgar Paez in Colombia series of attacks against the very existence of SINALTRAINAL have occurred in different Aregions of Colombia; ranging from a raid on the unionʼs national headquarters in Bogotá, to the assassination of one of our activists. These incidents are an example of President Álvaro Uribe Vélezʼs policy of ʻdemocratic securityʼ and take place at a diffi cult moment due to labour confl icts with the transnationals Nestlé and Coca-cola. These are some of the violent incidents against the lives and security of our members: Raid on union headquarters At approximately 12:15 a.m. on 3 August 2006, uniformed men who identifi ed themselves as members of SIJIN, the Judicial Police, entered into the headquarters of SINALTRAINAL located at No 35 – 18, 15th Avenue in Bogotá city and proceeded to search the union building stating it was a preventative operation for the upcoming 7 August, the inauguration day of president Álvaro Uribe Vélez. Police or thieves? US soldiers are deployed on every continent to defend Washington’s fi nancial interests Jacob Bailey That morning SIJIN agents were seen fi lming the outside of the unionʼs headquarters. This raid was carried out without a judicial order, being classifi ed curiously as an “act of voluntary registration”. -

Science 10Th Grade LEARNING OBJECT

Science 10th grade LEARNING OBJECT LEARNING UNIT How do the Colombian indigenous communities transform their environment? How do we transform our planet? S/K List the different indigenous communities in Colombia. Ask about the political system within some indigenous communities. Describe the infrastructure built by the indigenous communities in Colombia. Analyze the current situation of the indigenous communities with regard to the policies of Colombian agro-industrial megaprojects. Learn about the world view of the Colombian indigenous communities and compare it to your own. Express opinions in writing and share them orally in present tense. Language English Socio cultural context of Colombia the LO Curricular axis Living Environment. Standard competencies Explain biological diversity as a result of environmental, genetic and dynamic relationship changes within ecosystems. Background Knowledge Recognize that the Colombian population is multicultural and consists of different ethnic groups, each of which has its own specific social, political and cultural rights. English Review topic Inhabitant: a person or animal that lives in a particular place. Watershed: the area of land that includes a particular river or lake and all the rivers, streams, etc. that flow into it. Monoculture: the cultivation or growth of a single crop or organism especially on agricultural or forest land. Vocabulary box Present tense NAME: _________________________________________________ GRADE: ________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Read the following dialog Indigenous child: Did you know that we humans come from the knee of the god Gútapa? White child: From the knee of God Gútapa? Indigenous child: Yes, one day Gútapa was taking a bath in the creek, and some wasps stung her in her knees, they swelled up and from there emerged Ipi and Yoi. -

Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No

Report No. 56565-PA Investigation Report Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No. 7045-PAN) September 16, 2010 About the Panel The Inspection Panel was created in September 1993 by the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank to serve as an independent mechanism to ensure accountability in Bank operations with respect to its policies and procedures. The Inspection Panel is an instrument for groups of two or more private citizens who believe that they or their interests have been or could be harmed by Bank-financed activities to present their concerns through a Request for Inspection. In short, the Panel provides a link between the Bank and the people who are likely to be affected by the projects it finances. Members of the Panel are selected “on the basis of their ability to deal thoroughly and fairly with the request brought to them, their integrity and their independence from the Bank’s Management, and their exposure to developmental issues and to living conditions in developing countries.”1 The three-member Panel is empowered, subject to Board approval, to investigate problems that are alleged to have arisen as a result of the Bank having failed to comply with its own operating policies and procedures. Processing Requests After the Panel receives a Request for Inspection it is processed as follows: • The Panel decides whether the Request is prima facie not barred from Panel consideration. • The Panel registers the Request—a purely administrative procedure. • The Panel sends the Request to Bank Management, which has 21 working days to respond to the allegations of the Requesters. -

Fish Community Assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers Within the Naso-Teribe Territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible Implications of Bonyic Dam

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2017 Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Austin, Shaylyn, "Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam." (2017). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2560. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2560 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin University of Michigan School for International Training: Panama, Spring 2017 1 I. Abstract In the Changuinola/Teribe watershed of Bocas Del Toro, Panama, changes to the fluvial system due to the recently constructed Bonyic Dam have implications connected to the biodiversity of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the livelihoods of thousands of people of the Naso-Teribe indigenous group. This study investigated the composition of fish communities in 6 study sites in 3 different areas in relation to the Bonyic Dam. -

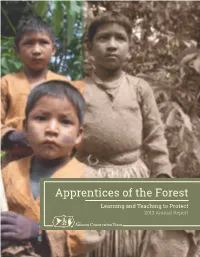

Apprentices of the Forest: 2013 Annual Report

Apprentices of the Forest Learning and Teaching to Protect 2013 Annual Report Letter from the President In all of its activities, ACT seeks partners who the old sciences have much to teach the new share this belief. When assessing partnerships sciences about adaptation—in effect, we with indigenous groups, ACT favors those should all be apprentices. communities with the greatest commitment to learning how to adapt and thrive under As the conservation story continues to evolve, rapidly changing ecological, social, and political ACT’s flexible, ambitious, and unwavering contexts. These kind of people possess the commitment to learning and traditional necessary drive to protect their traditional knowledge will ensure that we remain a territory and knowledge, as well as to transmit cutting-edge and resilient organization at the this capacity to future generations and forefront of the battle. neighboring groups. Since its inception, ACT has relied upon the bridging and blending of modern and ancient ways of knowing to forge the most effective solutions in biocultural conservation. In this effort, equally useful information and lessons can be obtained from scientific publications, Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D., L.H.D. novel technologies, or fireside chats with tribal President and Cofounder In 2013, scientists made a remarkable discovery chieftains. In the example of the olinguito in the cloud forests of Ecuador and Colombia: discovery mentioned previously, the carnivore the first new carnivorous mammalian species would likely have been recognized as unique identified in the Americas in 35 years. years earlier if researchers had consulted more Amazingly, one specimen of this fluffy relative closely with local indigenous groups. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

INDIGENOUS MOBILIZATION, INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND RESISTANCE: THE NGOBE MOVEMENT FOR POLITICAL AUTONOMY IN WESTERN PANAMA By OSVALDO JORDAN-RAMOS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Osvaldo Jordan Ramos 2 A mi madre Cristina por todos sus sacrificios y su dedicacion para que yo pudiera terminar este doctorado A todos los abuelos y abuelas del pueblo de La Chorrera, Que me perdonen por todo el tiempo que no pude pasar con ustedes. Quiero que sepan que siempre los tuve muy presentes en mi corazón, Y que fueron sus enseñanzas las que me llevaron a viajar a tierras tan lejanas, Teniendo la dignidad y el coraje para luchar por los más necesitados. Y por eso siempre seguiré cantando con ustedes, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama la gente. Toca el tambor, llama a la gente, Toca la caja, llama a la gente, Toca el acordeón, llama a la gente... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to recognize the great dedication and guidance of my advisor, Philip Williams, since the first moment that I communicated to him my decision to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Florida. Without his encouragement, I would have never been able to complete this dissertation. I also want to recognize the four members of my dissertation committee: Ido Oren, Margareth Kohn, Katrina Schwartz, and Anthony Oliver-Smith.