Pdf | 544.85 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests

THE POSITION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TROPICAL FORESTS Gerard A. Persoon Tessa Minter Barbara Slee Clara van der Hammen Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2004 Gerard A. Persoon, Tessa Minter, Barbara Slee and Clara van der Hammen The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests (Tropenbos Series 23) Cover: Baduy (West-Java) planting rice ISBN 90-5113-073-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2004 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International. No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microfilm, and electromagnetic record without prior written permission. Photos: Gerard A. Persoon (cover and Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7), Carlos Rodríguez and Clara van der Hammen (Chapter 5) and Barbara Slee (Chapter 6) Layout: Blanca Méndez CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 1. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND NATURAL RESOURCE 3 MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL POLICY GUIDELINES 1.1 The International Labour Organization 3 1.1.1 Definitions 4 1.1.2 Indigenous peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 5 management 1.1.3 Resettlement 5 1.1.4 Free and prior informed consent 5 1.2 World Bank 6 1.2.1 Definitions 7 1.2.2 Indigenous Peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 7 management 1.2.3 Indigenous Peoples’ Development Plan and resettlement 8 1.3 UN Draft Declaration on the -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Vitality of Damana, the Language of the Wiwa Indigenous Community

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-24-2020 3:00 PM Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce, The University of Western Ontario : Trillos Amaya, Maria, Universidad del Atlantico A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Hispanic Studies © Tatiana L. Fernandez Fernandez 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fernandez Fernandez, Tatiana L., "Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa Indigenous community" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7134. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7134 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Vitality of Damana, the language of the Wiwa People The Wiwa are Indigenous1 people who live in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia. This project examines the vitality of Damana [ISO 693-3: mbp], their language, in two communities that offer high school education in Damana and Spanish. Its aim is to measure the level of endangerment of Damana according to the factors used in the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected through a questionnaire that gathered demographic and background language information, self-reported proficiency and use of Spanish and Damana [n=56]. -

El Caribe: Origen Del Mundo Moderno

EL CARIBE: ORIGEN DEL MUNDO MODERNO Editoras Consuelo Naranjo Orovio Mª Dolores González-Ripoll Navarro María Ruiz del Árbol Moro EL CARIBE: ORIGEN DEL MUNDO MODERNO Consuelo Naranjo Orovio, Mª Dolores González-Ripoll Navarro y María Ruiz del Árbol Moro (editoras) “Connected Worlds: The Caribbean, Origin of Modern World”. Este proyecto ha recibido fondos del programa de investigación e innovación Horizon 2020 de la Unión Europea en virtud del acuerdo de subvención Marie Sklodowska-Curie Nº 823846. El proyecto está dirigido por la profesora Consuelo Naranjo Orovio del Instituto de Historia-CSIC. CRÉDITOS I. EL ESPACIO CARIBE VI –PROCESOS HISTÓRICOS EN EL CARIBE Mª Dolores González-Ripoll Navarro (Instituto de José Calderón (Universidad Ana G. Méndez, Gurabo, Historia-CSIC, España) Puerto Rico) Nayibe Gutiérrez Montoya (Universidad Pablo de Justin Daniel (Université des Antilles, Martinica) Olavide, España) Wilson E. Genao (Pontificia Universidad Católica Emilio Luque Azcona (Universidad de Sevilla, España) Madre y Maestra, República Dominicana) Juan Marchena Fernández (Universidad Pablo de Roberto González Arana (Universidad del Norte, Olavide, España) Colombia) Héctor Pérez Brignoli (Universidad de Costa Rica) Christine Hatzky (Leibniz University Hannover, Germany) Miguel Ángel Puig-Samper (Instituto de Historia-CSIC, Félix R. Huertas (Universidad Ana G. Méndez, Gura- España) bo, Puerto Rico) Mu-Kien A. Sang Ben (Pontificia Universidad Católica Héctor Pérez Brignoli (Universidad de Costa Rica) Madre y Maestra, República Dominicana) Carmen Rosado (Universidad Ana G. Méndez, Gurabo, Puerto Rico) II. LA TRATA ATLÁNTICA Antonio Santamaría García (Instituto de Historia-CSIC, Manuel F. Fernández Chaves (Universidad de Sevilla, España) España) Leida Fernández Prieto (Instituto de Historia-CSIC, VII. EL AZÚCAR EN EL MUNDO ATLÁNTICO España) Antonio Santamaría García (Instituto de Historia-CSIC, Rafael M. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED E NATIONS Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 24 February 2004 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH/SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Item 6 of the provisional agenda RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION Report by Mr. Doudou Diène, Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance Addendum MISSION TO COLOMBIA* ** * The summary of this report is being circulated in all official languages. The report itself is contained in the annex to this document and is being circulated in English, French and Spanish. ** This document is submitted late so as to include the most up-to-date information possible. GE.04-11140 (E) 150304 170304 E/CN.4/2004/18/Add.3 page 2 Summary In accordance with his mandate, the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance visited Colombia from 27 September to 11 October 2003 at the invitation of the Colombian Government. The visit made it possible to evaluate the progress achieved in the implementation of policies and measures to improve the situation of Afro-Colombians and indigenous populations, particularly following the visit of the former Special Rapporteur, Mr. Maurice Glèlè-Ahanhanzo, in 1996 (see E/CN.4/1997/71/Add.1, paras. 66-68). The Special Rapporteur also examined the situation of the Roma, a people that has apparently been excluded from Colombian ethno-demographic data. The Roma, who receive very little attention from human rights defenders, consider themselves to be victims of age-old discrimination. -

LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION of the COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL Offensive Sharpens

Reviews BuenaventuraBuenaventura LiberationLiberation more.. and footballfootball massacremassacre ofof MotherMother EarthEarth 12 dead and still no justice Indigenous peoples and We speak to the mothers of the battle of Cauca Valley Colombia’s lost sons page 19 . page 13 FRONTLINE LATIN AMERICA September - December 2006 PUBLICATION OF THE COLOMBIA SOLIDARITY CAMPAIGN Vol 2 No 4 Price £1.00 SINALTRAINAL offensive sharpens Edgar Paez in Colombia series of attacks against the very existence of SINALTRAINAL have occurred in different Aregions of Colombia; ranging from a raid on the unionʼs national headquarters in Bogotá, to the assassination of one of our activists. These incidents are an example of President Álvaro Uribe Vélezʼs policy of ʻdemocratic securityʼ and take place at a diffi cult moment due to labour confl icts with the transnationals Nestlé and Coca-cola. These are some of the violent incidents against the lives and security of our members: Raid on union headquarters At approximately 12:15 a.m. on 3 August 2006, uniformed men who identifi ed themselves as members of SIJIN, the Judicial Police, entered into the headquarters of SINALTRAINAL located at No 35 – 18, 15th Avenue in Bogotá city and proceeded to search the union building stating it was a preventative operation for the upcoming 7 August, the inauguration day of president Álvaro Uribe Vélez. Police or thieves? US soldiers are deployed on every continent to defend Washington’s fi nancial interests Jacob Bailey That morning SIJIN agents were seen fi lming the outside of the unionʼs headquarters. This raid was carried out without a judicial order, being classifi ed curiously as an “act of voluntary registration”. -

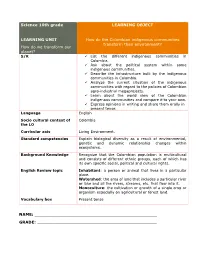

Science 10Th Grade LEARNING OBJECT

Science 10th grade LEARNING OBJECT LEARNING UNIT How do the Colombian indigenous communities transform their environment? How do we transform our planet? S/K List the different indigenous communities in Colombia. Ask about the political system within some indigenous communities. Describe the infrastructure built by the indigenous communities in Colombia. Analyze the current situation of the indigenous communities with regard to the policies of Colombian agro-industrial megaprojects. Learn about the world view of the Colombian indigenous communities and compare it to your own. Express opinions in writing and share them orally in present tense. Language English Socio cultural context of Colombia the LO Curricular axis Living Environment. Standard competencies Explain biological diversity as a result of environmental, genetic and dynamic relationship changes within ecosystems. Background Knowledge Recognize that the Colombian population is multicultural and consists of different ethnic groups, each of which has its own specific social, political and cultural rights. English Review topic Inhabitant: a person or animal that lives in a particular place. Watershed: the area of land that includes a particular river or lake and all the rivers, streams, etc. that flow into it. Monoculture: the cultivation or growth of a single crop or organism especially on agricultural or forest land. Vocabulary box Present tense NAME: _________________________________________________ GRADE: ________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Read the following dialog Indigenous child: Did you know that we humans come from the knee of the god Gútapa? White child: From the knee of God Gútapa? Indigenous child: Yes, one day Gútapa was taking a bath in the creek, and some wasps stung her in her knees, they swelled up and from there emerged Ipi and Yoi. -

Directorio De Traductores E Interpretes

DIRECCIÓN DE POBLACIONES Traductores e Intérpretes de lenguas nativas No Apellidos Nombres Lengua Teléfonos Correo electrónico LUGAR DE RESIDENCIA 3142128509 1 Ruiz Jose del Carmen Achagua [email protected] Puerto Gaitán, Meta 3134856006 1 Martinez Ramon Achagua 3142786590 [email protected] 2 Andoque Adán Andoque 3143298079 La Chorrera, Amazonas 2 Andoke Eli/ Iris Andoque 320 3303731 [email protected] 3 Torres Adriano Tomás Arhuaco 3183258830 [email protected] Bogotá D.C. 3 Torres Noel Arhuaco 3157592783 3 Chaparro Miguel Angel Arhuaco 3153747221 [email protected] Bogotá D.C. 3 Torres Ana Arhuaco 316 2368511 [email protected] 4 Ortiz Oscar Awá 3117899773 [email protected] Pasto, Nariño 4 Tengana Martin Efrain Awá 3155818019 4 Ortiz Oscar Awá 3117899773 [email protected] 5 Londoño Mario Bará 312 7674311 [email protected] 6 Rodriguez Jhonier Barasano [email protected] 7 Oriara Orocora Jaime Undara Barí 310 7996167 Tibú, Norte de Santander 7 Abeidora Laura Barí 3115191001 [email protected] Tibú, Norte de Santander 7 Eliseth Amacumashara Barí 3212199766 amacubara-centro28 @hotmail.com Tibú, Norte de Santander 8 Bosco Gonzalés Juan Bora [email protected] La Chorrera, Amazonas 8 Teteye Juan Benito Bora 3127023036 [email protected] La Chorrera, Amazonas 8 Teteye Alejandro Bora 310 8631124 9 Sanchez Pablo CABIYARI 385253603 Compartel Buenos Aires 10 Sanchéz Germán Miguel Carapana 3115765385 [email protected] Mitú, Vaupés 10 Vargas Angie Carapana 320 9717045 11 Carijona -

Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Santiago, 2021 FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest governance by indigenous and or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. tribal peoples. An opportunity for climate action in Latin If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under America and the Caribbean. Santiago. FAO. the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If a https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en translation of this work is created, it must include the following disclaimer along with the required citation: The designations employed and the presentation of “This translation was not created by the Food and material in this information product do not imply the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United this translation. The original English edition shall be the Nations (FAO) or Fund for the Development of the authoritative edition.” Indigenous Peoples of Latina America and the Caribbean (FILAC) concerning the legal or development status of Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or licence shall be conducted in accordance with the concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on The mention of specific companies or products of International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) as at present in force. -

Herederos Del Jaguar Y La Anaconda

HEREDEROS DEL JAGUAR Y LA ANACONDA NINA S. DE FRIEDEMANN Y JAIME AROCHA antropología HEREDEROS DEL JAGUAR Y LA ANACONDA NINA S. DE FRIEDEMANN Y JAIME AROCHA antropología Catalogación en la publicación – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia Sánchez de Friedemann, Nina, 1935-1998, autor Arocha Rodríguez, Jaime, 1945-, autor Herederos del jaguar y la anaconda / Nina S. de Friedemann y Jaime Arocha ; presentación, Carlos Guillermo Páramo Bonilla. – Bogotá : Ministerio de Cultura : Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, 2016. 1 recurso en línea : archivo de texto PDF (560 páginas). – (Biblioteca Básica de Cultura Colombiana. Antropología / Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia) Incluye glosario e índice onomástico. -- Referencias bibliográficas al final de cada ensayo. ISBN 978-958-8959-52-8 1. Etnología – Historia – Colombia 2. Antropología – Historia - Colombia 3. Culturas indígenas - Colombia 4. Indígenas de Colombia - Vida social y costumbres 5. Libro digital I. Páramo Bonilla, Carlos Guillermo, autor de introducción II. Título III. Serie CDD: 305.8009861 ed. 23 CO-BoBN– a994091 Mariana Garcés Córdoba MINISTRA DE CULTURA Zulia Mena García VICEMINISTRA DE CULTURA Enzo Rafael Ariza Ayala SECRETARIO GENERAL Consuelo Gaitán DIRECTORA DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL Javier Beltrán José Antonio Carbonell COORDINADOR GENERAL Mario Jursich Julio Paredes Jesús Goyeneche COMITÉ EDITORIAL ASISTENTE EDITORIAL Y DE INVESTIGACIÓN Taller de Edición • Rocca® REVISIÓN Y CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS, DISEÑO EDITORIAL Y DIAGRAMACIÓN eLibros CONVERSIÓN DIGITAL PixelClub S. A. S. ADAPTACIÓN DIGITAL HTML Adán Farías CONCEPTO Y DISEÑO GRÁFICO Con el apoyo de: BibloAmigos ISBN: 978-958-8959-52-8 Bogotá D. C., diciembre de 2016 © Jaime Arocha Rodríguez © 1989, Carlos Valencia Editores © 2016, De esta edición: Ministerio de Cultura – Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia © Presentación: Carlos Guillermo Páramo Bonilla Material digital de acceso y descarga gratuitos con fines didácticos y culturales, principalmente dirigido a los usuarios de la Red Nacional de Bibliotecas Públicas de Colombia. -

Las Vicisitudes De La Enseñanza De Lenguas En Colombia

Diálogos Latinoamericanos 15, 2009 Las vicisitudes de la enseñanza de lenguas en Colombia Sergio Torres-Martínez1 Caught in the turmoil of our troubled educational system, foreign language teaching in Colombia struggles to find its way into modernity despite extensive learning consumerism. Considered one of the linchpins of the country’s cultural homologation in the international community, language teaching discourse remains aloft in its technocratic bubble eager to meet foreign standards. The present article seeks to present an overview of our educational scenario from a socio- cultural perspective, unveiling the political agenda behind language teaching policies, taken over by a neoliberal ideology that disregards the vexing truth: In Colombia, education is far from being considered an asset for people’s progress. Keywords: Foreign language teaching – education – linguistic policies – bilingualism – cultural homologation – globalisation. 1. Introducción Si bien el centro de reflexión del presente artículo es la enseñanza de las lenguas extranjeras en nuestro país, considero necesario hacer una aclaración preliminar: no es posible hablar de enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en Colombia sin indagar en el trasegar de nuestra educación como metáfora formativa civilizadora y, a la vez, como un escenario más de las paradojas que caracterizan a los pueblos de América Latina. En efecto, la noción de educación en Colombia está atravesada por el conflicto entre lo jurídico y lo operativo enmarcado en un orden político-legal que se esfuerza por ser consecuente con los estándares internacionales pero que carece de los medios (¿o de la imaginación?) para operar un cambio real. Un conflicto que dilata con discusiones teóricas la acción hacia el mejoramiento de la calidad de la educación maquillando los verdaderos resultados con indicadores como la cobertura (escolarización= retención) o el aumento del número de estudiantes (uso del espacio= cupos escolares). -

Herederos Del Jaguar Y La Anaconda Nina S

Herederos del jaguar y la anaconda Nina S. de Friedemann, Jaime Arocha Contenido SEPULCROS HISTÓRICOS Y CRÓNICAS DE CONQUISTA ...................................................... 3 PREFACIO ....................................................................................................................................... 25 PRÓLOGO A LA EDICIÓN DE 1982 ............................................................................................. 30 1. DEL JAGUAR Y LA ANACONDA ............................................................................................ 35 2. GUAHÍBOS: maestros de la supervivencia .................................................................................. 60 3. AMAZÓNICOS: gente de ceniza, anaconda y trueno .................................................................. 86 4. SIBUNDOYES E INGAS: sabios en medicina y botánica ......................................................... 120 5. CAUCA INDIO: guerreros y adalides de paz ............................................................................. 152 6. EMBERAES: escultores de espíritus .......................................................................................... 184 7. CUNAS: parlamentarios y poetas ............................................................................................... 208 8. COGUIS: guardianes del mundo ................................................................................................. 232 9. GUAJIROS: amos de la arrogancia y del cacto .........................................................................