Building a Community Language Development Team with Québec Naskapi Bill Jancewicz, Marguerite Mackenzie, George Guanish, Silas Nabinicaboo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

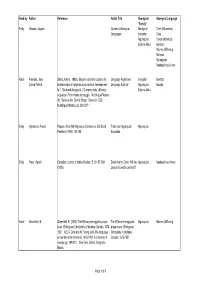

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

Download (7MB)

- "SMALL" TALK: THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF THE DIMINUTIVE SUFFIX IN NORTHERN EAST CREE by © Amanda Cunningham A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland May 11, 2008 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract Diminutivization is a morphological process that is commonly attested among the world's languages. Though it has been studied in numerous languages belonging to a variety of language families, there has been a limited amount of research conducted on the diminutive in Algonquian. This thesis examines the diminutive suffix in Northern East Cree (NEC), a subdialect of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi which is a Central Algonquian language spoken in Quebec. Comparisons, where possible, are made with other Algonquian dialects for which there is diminutive data. The phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic properties of the particle, nominal, and verbal diminutive in NEC are described. There is a particular focus on the verbal diminutive, the investigation of which analyzes its distribution by identifying what elements of the sentence (subject, object, and/or verb) it modifies within each of the four Algonquian verb classes. The extent to which the Algonquian diminutive behaves like inflectional morphology is also discussed. 11 Acknowledgments Completion of a project of this magnitude can never be achieved by just one individual. I owe my success to a number of people and organizations. First, and foremost, I must acknowledge the amazing team of faculty, administrative staff, and graduate students that comprise the Linguistics Department at MUN. -

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh 37th Algonquian Conference, Ottawa 2005 Bill Jancewicz SIL International and Naskapi Development Corporation ABSTRACT Submitted as an update to a presentation made at the 34th Algonquian Conference (Kingston). The ongoing development of the operating systems has included increased support for cross-platform use of Unicode syllabic script. Key improvements that were included in Macintosh's OS X.3 (Panther) operating system now allow direct keyboarding of Unicode characters by means of a user-defined input method. A summary and comparison of the available tools for handling Unicode on both Windows and Macintosh will be discussed. INTRODUCTION Since 1988 the author has been working in the Naskapi language at Kawawachikamach with the primary purpose of linguistic analysis and Bible translation, sponsored by Wycliffe Bible Translators and SIL International. Related work includes mother tongue translator training, Naskapi literature and curriculum development. Along with the language work the author also developed methods of production for Naskapi language materials in syllabic script by means of the computer. With the advent of high quality publishing capabilities in newer computers, procedures were updated to keep pace with the improving technology. With resources available from SIL International computer services department, a very satisfactory system of keyboarding syllabic texts in Naskapi was developed. At the urging of colleagues working in related languages, the system was expanded to include the wider inventory of standard Eastern and Western Cree syllabics. While this has pushed the limit of what is possible with the current technology, Unicode makes this practical. Note that the system originally developed for keyboarding Naskapi syllabics is similar but not identical to the Cree system, because of the unique local orthography in use at Kawawachikamach. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

Including Indigenous languages in education: An analysis of Canadian policy documents by Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft B.A. (Hons.), University of Alberta, 2012 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, education, satire, parody, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft Degree: Master of Arts Title: Including Indigenous languages in education: An analysis of Canadian policy documents Examining Committee: Chair: Yue Wang Associate Professor John D. Mellow Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Suzanne Hilgendorf Supervisor Associate Professor Patricia Shaw External Examiner Professor Department of Anthropology University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: August 05, 2016 ii Abstract Language policy may promote or reduce the use and acquisition of languages. Indigenous languages in Canada are endangered and the number of speakers of these languages is declining. In this thesis, I examine a number of Canadian language policies in order to analyse whether provisions exist for including Indigenous languages within educational programmes. Previous studies of Canadian language policies have often only briefly addressed Indigenous languages. My analysis considers some of the policy documents discussed in earlier studies (e.g. the 1969 Official Languages Act), some recent policy documents (e.g. -

Proof of the Algonquian-Wakashan Relationship

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 1: Proof of the Algonquian-Wakashan relationship The first part of the present study, following a general introduction (§ 1), presents a classifi- cation and approximate glottochronological dating for the Algonquian-Wakashan languages (§ 2), a preliminary discussion of regular sound correspondences between Proto-Wakashan, Proto-Nivkh, and Proto-Algic (§ 3), and an analysis of the Algonquian-Wakashan “basic lexi- con” (§ 4). The main novelty of the present article is in its attempt at formal demonstration of a genetic relationship between the Nivkh, Algic, and Wakashan languages, arrived at by means of the standard comparative method, i. e. establishing a system of regular sound cor- respondences between the vocabularies of the compared languages. Proto-Salishan is con- sidered as a remote relative of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan; at the same time, no close (“Mosan”) relationship between Wakashan and Salish has been traced. Additionally, lexical correspondences between Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan, Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan, and Proto-Salishan are also reviewed. The conclusion is that no genetic relationship exists be- tween Chukchi-Kamchatkan, on the one hand, and Algonquian-Wakashan, languages (Nivkh included), on the other hand. Instead, it seems more likely that Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan has borrowed words from Wakashan, Salishan, and Algic (but probably not vice versa; § 5). The Algonquian-Wakashan, Salishan and Chukchi-Kamchatkan common cultural lexicon is also examined, resulting in the identification of numerous “cultural” loans from Wakashan and Salish into Proto-Chukchi-Kamchatkan. Borrowing from Salishan into Proto-Nivkh was far less intensive, as there are no reliable Nivkh-Wakashan contact words. -

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach Annual Report 2009-10 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010 Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach | ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 | 1 2 | Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach | ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 Message | From the Chief On behalf of Council, I am pleased to present the Annual Report for the 2009-10 fiscal year. Through the collective efforts of Council and many individuals and organizations, we accomplished a great deal in the fiscal year under review. Some of the highlights include: • the signing of the Naskapi-Québec Partnership Agreement; • the expansion of cellular telephone service by Lynx Mobility Inc.; • the continuation of the exercise programme at the Recreation Facility to combat the increasing incidence of diabetes among our members; and • the Healing Canoe Journey and the Uashat Youth Gathering. Despite our successes and accomplishments, there are challenges that we continue to face: • the payment of rent for housing. Although there are tenants who are up-to-date with their rent payments, many have arrears. This means that Council is essentially subsidizing those tenants who have arrears rather than paying for further housing maintenance and additional house construction. All tenants, including persons living with them, are strongly encouraged to pay rent, including arrears, on a regular basis; and • vandalism to houses and public buildings. A reduction in vandalism will reduce repair costs, and the savings could then be applied to house maintenance and construction or to other community priorities. Council appeals to all community members to join together and meet these and the other challenges facing our community. We would also like to express our appreciation to everyone who helps to build and enrich our community through their active involvement in boards and committees, and to those individuals who volunteer their time to help implement community initiatives, especially those that benefit our Elders and youths. -

Innu-Aimun) in Labrador1

A SURVEY OF RESEARCH ON MONTAGNAIS AND NASKAPI (INNU-AIMUN) IN LABRADOR1 Marguerite MacKenzie Memorial University of Newfoundland ABSTRACT The last two decades have seen increased interest in the study of the language of the Innu of Labrador. Researchers from Memorial University of Newfoundland have been prominent in producing descriptions of grammar, lexicon and linguistic variation in the community of Sheshatshit. Anthropologists have been active in the collection of texts and toponyms. This article gives an overview of work to date in these areas. 1. INTRODUCTION The language spoken by the Innu of Labrador, known to linguists as Montagnais / Naskapi, represents two dialects of the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex of the Algonquian language family. The Montagnais sub-group is spoken by about 10,000 people in eight communities in Québec and one in Labrador (see Map). In Sheshatshit, (formerly known as North West River) there are about 2,000 speakers. To the north, Naskapi is spoken by about 500 people in Davis Inlet, also known as Utshimassits. Speakers refer to both dialects as Innu- aimun, qualifying this term as necessary. Innu-aimun is still the first language of virtually all residents of the two Labrador communities, with English as the second language. In Québec, where French is the second language, a significant number of Innu, particularly in the western communities, now use French as a first language. In Labrador most speakers under the age of forty are now bilingual to some extent in Innu-aimun and English, since English is the language of schooling. The extent to which this language will join or resist the widespread decline of Aboriginal languages as first languages remains to be documented. -

Indigenous Languages in Canada

ᐁᑯᓯ ᒫᑲ ᐁᑎᑵ ᐊᓂᒪ ᑳᐃᑘᐟ ᐊᐘ ᐅᐢᑭᓃᑭᐤ , ᒥᔼᓯᐣ, ᑮᐢᐱᐣ ᑕᑲᑵᓂᓯᑐᐦᑕᒣᐠ ᐁᑿ ᒦᓇ ᑕᑲᑵᒥᑐᓂᐑᒋᐦᐃᓱᔦᐠ ᐊᓂᒪ, ᐆᒪ ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ ᑭᐢᐱᐣ ᑭᓅᐦᑌᑭᐢᑫᔨᐦᑌᓈᐚᐤ᙮ ᐆᒪ ᐆᑌ INDIGENOUSᑳᐃᑕᐱᔮᕽ ᓵᐢᑿᑑᐣ, ᐁᑯᓯ ᐃᓯ ᐆᒪ ᓂᑲᑵᒋᒥᑲᐏᓈᐣ ᑮᑿᕀ ᐁᓅᐦᑌᑭᐢᑫᔨᐦᑕᐦᑭᐠ ᐁᑯᓯ ᐃᓯLANGUAGESᐆᒪ ᐹᐦᐯᔭᐠ ᐆᒥᓯ ᐃᓯ , ᓂᑮᑭᑐᑎᑯᓈᓇᐠ IN CANADA, “ᑮᒁᕀ ᐊᓂᒪ ᐁᐘᑯ᙮ ᑖᓂᓯ ᐊᓂᒪ ᐁᐘᑯ ᐁᐃᑘᒪᑲᕽ ᐲᑭᐢᑵᐏᐣ᙮” ᐁᑯᓯ ᐃᑘᐘᐠ, ᐁᐘᑯ ᐊᓂᒪ ᐁᑲᑵᒋᒥᑯᔮᐦᑯᐠ, ᐁᑯᓯ ᐏᔭ ᐁᑭᐢᑫᔨᐦᑕᒫᕽ ᐊᓂᒪ, ᑮᒁᕀ ᑳᓅᐦᑌ ᑭᐢᑫᔨᐦᑕᐦᑭᐠ, ᐁᑯᓯ ᓂᑕᑎ ᐑᐦᑕᒪᐚᓈᓇᐠ, ᐁᑯᓯ ᐁᐃᓰᐦᒋᑫᔮᕽ ᐆᑌ ᓵᐢᑿᑑᐣ, ᐁᑿ ᐯᔭᑿᔭᐠ ᐊᓂᒪ ᐁᑯᓯ ᐃᓯ ᐆᒪ ᐁᐊᐱᔮᕽ, ᐁᑿ ᐯᔭᑿᔭᐠ ᒦᓇ ᐃᐦᑕᑯᐣ = ᑭᐢᑫᔨᐦᑕᒼ ᐊᐘ ᐊᓂᒪ ᐃᑕ CANADIAN LANGUAGE MUSEUM ᒦᓇ ᐁᐊᐱᔮᕽMUSÉE CANADIEN= ᐁᑯᑕ DESᐱᓯᓯᐠ LANGUES ᑫᐦᑌ ᐊᔭᐠ᙮ ᐁᑯᑕ ᐁᑿ ᐁᑯᓂᐠ ᑳᓂᑕᐍᔨᐦᑕᐦᑭᐠ , ᒣᒁᐨ ᐆᒪ ᐁᐘᑯ ᐆᒪ ᐁᑿ ᑳᓅᒋᐦᑖᒋᐠ, ᐁᑯᑕ ᐊᓂᒪ ᓂᐑᒋᐦᐃᐚᐣ᙮ CANADIAN LANGUAGE MUSEUM Canadian Language Museum Glendon Gallery, Glendon College 2275 Bayview Avenue Toronto ON M4N 3M6 Printed with assistance from the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, York University, Toronto, Canada Copyright © 2019, Canadian Language Museum Author: Will Oxford Editor: Elaine Gold The Cree syllabic text on the cover, typeset by Chris Harvey, is an excerpt from a speech titled “Speaking Cree and Speaking English” by Sarah Whitecalf, published in kinêhiyâwiwininaw nêhiyawêwin / The Cree Language is Our Identity: The La Ronge Lec- tures of Sarah Whitecalf (University of Manitoba Press, 1993, ed. by H.C. Wolfart and Freda Ahenakew). Preface ................................................................................................................................... iii 1 Approaching the study of Indigenous languages ................................................ 1 1.1 Terms for Indigenous peoples and languages ............................................. -

Towards a Dialectology of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi

TOWARDS A DIALECTOLOGY OF CREE-MONTAGNAIS-NASKAPI by Marguerite Ellen MacKenzie Department of Anthropology A Thesis submitted in conformity with requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Toronto MARGUERITE ELLEN MACKNZIE 1980 TOWARDS A DIALECTOLOGY of CREE - MONTAGNAIS - NASKAPI by Marguerite Ellen MacKenzie ABSTRACT This study describes linguistic variations among the dialects of the Cree language at the levels of phonology, morphology and lexicon. The dialects which undergo velar palatalization (k>c) within Quebec- Labrador are described in detail. The language spoken in these nineteen communities has been referred to as Cree, Montagnais, Naskapi or Montagnais-Naskapi by various scholars. Only the dialects where velar palatalization does not take place are unambiguously regarded as Cree. The relationship between the palatalized and non-palatalized dialects is examined and the dialects spoken between Alberta and Labrador are found to form a continuum. Within the continuum sub- groups are established but the existence of a significant break between non-palatalized (so-called Cree) and palatalized (so-called Montagnais-Naskapi) dialects is challenged. At the level of phonology it is demonstrated that the majority of sound shifts occur in both palatalized and non-palatalized dialects. Usually, however, these shifts are generalized to more phonological segments, and over a larger geographic area, in the palatalized dialects. Processes of short vowel assimilation, loss, neutralization and rounding are much more widespread. As well, the processes of velar palatalization, short vowel syncope and subsequent de-palatalized account for the majority of the differences between palatalized and non-palatalized dialects. These processes are linguistic innovations which originate in thee Quebec dialects, which have been longest in contact with European populations.