Volume 13, 1991 of NEW BRUNSWICK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1904 Anglo-French Newfoundland Fisheries Convention: Another Look

RESEARCH NOTES/NOTES DE RECHERCHE The 1904 Anglo-French Newfoundland Fisheries Convention: Another Look THE EXISTING LITERATURE ON ANGLO-FRENCH RELATIONS at the turn of the century, as well as that which specifically addresses the 1904 entente cordiale, for the most part makes only passing mention of the Newfoundland fisheries issue. Understandably, the focus of these accounts tends to be on the changing relations between the great powers, and on the most important aspect of the entente itself, which was the definition of boundaries and spheres of influence in North and West Africa. The exceptions are P.J.V. Rolo's study of the entente, which does recognize the crucial place of the fisheries issue in the context of the overall negotiation, and F.F. Thompson's brief account of the Newfoundland settlement from a colonial perspective in his standard work on the French, or Treaty, Shore question. i This note expands these accounts of the evolution of the 1904 Anglo-French Fisheries Convention, reinforces the view that it was vital to the successful completion of the overall package, and looks at the aftermath. This is not the place to discuss in detail the reasons for Anglo-French rapprochement which culminated in the 1904 entente cordiale. At the risk of oversimplification, one can point to several key factors. The Fashoda incident (1898) demonstrated, in time, to many French politicians that there was no hope of ending the resented British occupation of Egypt and the Nile valley. Confrontation with Britain in Africa was clearly futile, and accommodation potentially advantageous. Increasingly, the parti colonial urged the French government to consider giving up its financial and economic influence in Egypt, recognizing British predominance there, in return for British acceptance of France's ambition to establish a protectorate over Morocco and concessions elsewhere.2 Once this reasoning had been accepted and advanced by the French government, the British government eventually proved willing to respond positively (if carefully). -

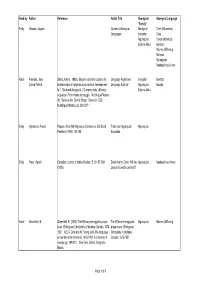

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Inclusion of Students with Special Education Needs in French As a Second Language Programs: a Review of Canadian Policy and Resource Documents

Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 183, 15-29 Inclusion of Students With Special Education Needs in French as a Second Language Programs: A Review of Canadian Policy and Resource Documents Stefanie Muhling, Ontario Ministry of Education & Callie Mady, Nipissing University Abstract This article describes a document analysis of policy and resource documents pertaining to inclu- sion of students with special education needs (SSEN) in Canadian French as a Second Language (FSL) programs. By recognizing gaps and acknowledging advancements, we aim to inform cur- rent implementation and future development of inclusive policy. Document analysis of a) special education documents and b) FSL policy and support documents revealed that over 80% of pro- vincial and territorial education ministries currently refer to inclusion of SSEN in FSL. With the intent of remediating identified inconsistencies in actual application, this article concludes with specific recommendations to enhance inclusive practice. Keywords: French as a second language (FSL), inclusion, second language education, special needs, students with special education needs Introduction Inclusion1 of students with special education needs2 (SSEN) in French as a second language (FSL) programs is an issue gaining increased attention throughout Canada, as educators are encouraged to strive for greater inclusion while at the same time, requiring additional support to do so (Lapkin, MacFarlane, & Vandergrift, 2006). As past and current incidences of exclusion come to the fore, educators, researchers, and policymakers are embarking upon more inclusive approaches to FSL programming. To both support such efforts, and to recognize the multiple sources of information across Canada, this article uses document analysis to reveal the state of inclusion in FSL programs. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

Aboriginal Languages and Selected Vitality Indicators in 2011

Catalogue no. 89-655-X— No. 001 ISBN 978-1-100-24855-4 Aboriginal Languages and Selected Vitality Indicators in 2011 by Stéphanie Langlois and Annie Turner Release date: October 16, 2014 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected], telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following toll-free numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 To access this product This product, Catalogue no. 89-655-X, is available free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca, and browse by “Key resource” > “Publications.” Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has developed standards of service that its employees observe. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “About us” > “The agency” > “Providing services to Canadians.” Standard symbols Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada The following symbols are used in Statistics Canada publications: . -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Newfoundland English

Izaro Zalacain Mendia Degree in English Studies 2019-2020 NEWFOUNDLAND ENGLISH Supervisor: Miren Alazne Landa Departamento de Filología Inglesa, Alemana y de Traducción e Interpretación Área de Filología Inglesa Abstract The English language has undergone many variations, leaving uncountable dialects in every nook and cranny of the world. Located at the north-east of Canada, the island of Newfoundland presents one of those dialects. However, within the many varieties the English language features, Newfoundland English (NE) remains as one of the less researched dialects in North America. The aim of this paper is to provide a characterisation of NE. In order to do so, this paper focuses on research questions on the origins of the dialect, potential variation within NE, the languages it has been in contact with, its particular linguistic features and the role of linguistic distinction in the Newfoundlander identity. Thus, in this paper I firstly assess the origins of NE, which are documented to mainly derive from West Country, England, and south-eastern Ireland, and I also provide an overview of the main historical events that have influenced the language. Secondly, I show the linguistic variation NE features, thus displaying the multiple dialectal areas that are found in the island. Furthermore, I discuss the different languages that have been in contact with the variety, namely, Irish Gaelic and Micmac, among others. Thirdly, I present a variety of linguistic features of NE -both phonetic and morphosyntactic- that distinguish the dialect from the rest of North American varieties, including Canadian English. Finally, I tackle the issue of language and identity and uncover a number of innovations and purposeful uses of certain features that the islanders show in their speech for the sake of identity marking. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) ; "\. A Linguistic Description of the French Spoken on the Port-au-Port Peninsula of Western Newfoundland by © Mary Geraldine Barter Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Memorial University of Newfoundland April 1986 :t.• Perm i ssion has been granted L'autorisation a ete accordee to the National Library of a la Bibliotheque nationale Canad a to microfilm this du Canada de microfilmer thesis and to lend or sell cette these et de preter ou copies of the film. de vendre des exemplaires du film. The author (copyright owner) L'auteur (titulai re du droit has reserved other d'auteur) se reserve les publication rights, and autres droits de publication; neithe r the thesis nor ni la these ni de longs extens ive extracts from it extraits de celle-ci ne may be printed or otherwise doivent etre imprimes ou reproduced without his/her autrement reproduits sans son writt en permission. autorisation ecrite. ISBN 0-315-31008-1 Table of Contents Page In trociuction l List of Abbreviations .......... ....... ...... 5 Acknowledgements 8 Chapter I . The French of the Port-au-Port Peninsula and Bay St. George: A Historical Perspective .......... 12 II. The French Spoken on the Port-au- Port Peninsula .................... 40 III. The Vocabulary .................... 78 IV. Phonetic Aspects .................. 140 Appendices 184 Informants 185 Recorded Text:.s A. Mme Elizabeth Barter, La Grand'Terre 207 B. Mrne Marguerite LeCour, L'Anse-a- Canards ........................... 212 c. Mrne Lucie Simon, Cap-St-Georges ... 217 Bibliography 222 List of Figures Page 1. -

Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-21-2020 Language, Identity, and Citizenship: Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920 Elisa E A Sance University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Canadian History Commons, Other Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Sance, Elisa E A, "Language, Identity, and Citizenship: Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3200. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3200 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE, IDENTITY, AND CITIZENSHIP: POLITICS OF EDUCATION IN MADAWASKA, 1842-1920 By Elisa Elisabeth Andréa Sance M.A. University of Maine, 2014 B.A. Université d’Angers, 2011 B.L.S. Université d’Angers, 2007 A.A. Université Picardie Jules Verne, 2006 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Advisor Scott W. See, Libra Professor Emeritus of History Richard W. Judd, Professor Emeritus of History Mazie Hough, Professor Emerita of History & Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Jane S. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions.