1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

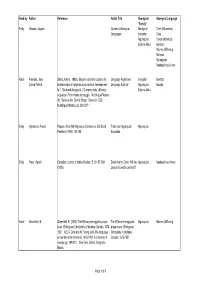

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

Lillooet Between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. Van Eijk First

Lillooet between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Although most details of the grammatical and lexical structure of Lillooet put this language firmly within the Interior branch of the Salish language family, Lillooet also shares some features with the Coast or Central branch. In this paper we describe some of the similarities between Lillooet and one of its closest Interior relatives, viz., Shuswap, and we also note some similarities be tween Lillooet and Sechelt, one of Lillooet' s western neighbours but belonging to the Coast branch. Particular attention is paid to some obvious loans between Lillooet and Sechelt. 1 Introduction Lillooet belongs with Shuswap to the Interior branch of the Salish language family, while Sechelt belongs to the Coast or Central branch. In what follows we describe the similarities and differences between Lillooet and both Shuswap and Sechelt, under the following headings: Phonology (section 2), Morphology (3), Lexicon (4), and Lillooet-Sechelt borrowings (5). Conclusions are given in 6. I omit a comparison between the syntactic patterns of these three languages, since my information on Sechelt syntax is limited to a brief text (Timmers 1974), and Beaumont 1985 is currently unavailable to me. Although borrowings between Lillooet and Shuswap have obviously taken place, many of these will be impossible to trace due to the close over-all resemblance between these two languages. Shuswap data are mainly drawn from the western dialects, as described in Kuipers 1974 and 1975. (For a description of the eastern dialects I refer to Kuipers 1989.) Lillooet data are from Van Eijk 1997, while Sechelt data are from Timmers 1973, 1974, 1977. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

On the Two Salish Object Agreement Suffixes*

On the Two Salish Object Agreement Suffixes* KAORU KIYOSAWA Simon Fraser University 0. Introduction Salish languages are famous for their rich morphological structures. They have a variety of affixes including lexical suffixes, transitive suffixes marking control and causation, and personal affixes. Among the personal affixes, some languages exhibit two sets of object suffixes. For example, Tillamook (Egesdal and Thompson 1998:250, 259) has two different forms for first-person singular object: -c in (1a) and -wš in (1b).1,2 (1) a. c-wԥ"-wi-c-Ø. 3 ST-RDP-leave-TR:1SG.(S)OBJ-3SUB ‘They left me.’ b. de š-s-gi-g9ԥ!ԥš-tí-wš-Ø. ART DSD-NM-RDP-kill-CS-1SG.(M)OBJ-3SUB ‘They want to kill me.’ In contrast, Thompson (1985:397, 394) has only one set of object suffixes, and thus -cm is the first-person singular object suffix in both (2a) and (2b). * I would like to thank Donna Gerdts, Paul Kroeber, and Charles Ulrich for their comments and advice. 1 Abbreviations for grammatical terms used in this paper are as follows. APPL applicative, ART article, ATN autonomous, AUX auxiliary, CONT continuative, CS causative, DAT dative, DET determiner, DIR directive, DSD desiderative, ERG ergative, FUT future, IMP imperative, NC non- control, NM nominalizer, NOM nominative, OBJ object, OBL oblique, PL plural, POSS possessor, PRT particle, PST past, RDP reduplication, SER serial, SG singular, ST stative, SUB subject, TR transitive. 2 I have standardized hyphenations and glosses in the cited examples and regularized the orthography following Kroeber (1999). Any mistakes or misinterpretations are my own. -

Language Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86573-9 - Endangered Languages: An Introduction Sarah G. Thomason Index More information Language index ||Gana, 106, 110 Bininj, 31, 40, 78 Bitterroot Salish, see Salish-Pend d’Oreille. Abenaki, Eastern, 96, 176; Western, 96, 176 Blackfoot, 74, 78, 90, 96, 176 Aboriginal English (Australia), 121 Bosnian, 87 Aboriginal languages (Australia), 9, 17, 31, 56, Brahui, 63 58, 62, 106, 110, 132, 133 Breton, 25, 39, 179 Afro-Asiatic languages, 49, 175, 180, 194, 198 Bulgarian, 194 Ainu, 10 Buryat, 19 Akkadian, 1, 42, 43, 177, 194 Bushman, see San. Albanian, 28, 40, 66, 185; Arbëresh Albanian, 28, 40; Arvanitika Albanian, 28, 40, 66, 72 Cacaopera, 45 Aleut, 50–52, 104, 155, 183, 188; see also Bering Carrier, 31, 41, 170, 174 Aleut, Mednyj Aleut Catalan, 192 Algic languages, 97, 109, 176; see also Caucasian languages, 148 Algonquian languages, Ritwan languages. Celtic languages, 25, 46, 179, 183, Algonquian languages, 57, 62, 95–97, 101, 104, 185 108, 109, 162, 166, 176, 187, 191 Central Torres Strait, 9 Ambonese Malay, see Malay. Chadic languages, 175 Anatolian languages, 43 Chantyal, 31, 40 Apache, 177 Chatino, Zenzontepec, 192 Apachean languages, 177 Chehalis, Lower, see Lower Chehalis. Arabic, 1, 19, 22, 37, 43, 49, 63, 65, 101, 194; Chehalis, Upper, see Upper Chehalis. Classical Arabic, 8, 103 Cheyenne, 96, 176 Arapaho, 78, 96, 176; Northern Arapaho, 73, 90, Chinese languages (“dialects”), 22, 35, 37, 41, 92 48, 69, 101, 196; Mandarin, 35; Arawakan languages, 81 Wu, 118; see also Putonghua, Arbëresh, see Albanian. Chinook, Clackamas, see Clackamas Armenian, 185 Chinook. -

Sherry Simon Hybridity Revisited: St

Editorial Board / Comité de rédaction Editor-in-Chief Rédacteur en chef Robert S. Schwartzwald, University of Massachusetts Amherst, U.S.A. Associate Editors Rédacteurs adjoints Claude Couture, Faculté St-Jean, Université de l’Alberta, Canada Marta Dvorak, Université de Paris III, France Daiva Stasiulis, Carleton University, Canada Managing Editor Secrétaire de rédaction Guy Leclair, ICCS/CIEC, Ottawa, Canada Advisory Board / Comité consultatif Malcolm Alexander, Griffith University, Australia Rubén Alvaréz, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Venezuela Shuli Barzilai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israël Raymond B. Blake, University of Regina, Canada Nancy Burke, University of Warsaw, Poland Francisco Colom, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Spain Beatriz Diaz, Universidad de La Habana, Cuba Giovanni Dotoli, Université de Bari, Italie Eurídice Figueiredo, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brésil Madeleine Frédéric, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgique Naoharu Fujita, Meiji University, Japan Gudrun Björk Gudsteinsdottir, University of Iceland, Iceland Leen d’Haenens, University of Nijmegen, Les Pays-Bas Vadim Koleneko, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia Jacques Leclaire, Université de Rouen, France Laura López Morales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico Jane Moss, Romance Languages, Colby College, U.S. Elke Nowak, Technische Universität Berlin, Germany Helen O’Neill, University College Dublin, Ireland Christopher Rolfe, The University of Leicester, U.K. Myungsoon Shin, Yonsei University, Korea Jiaheng Song, Université de Shantong, Chine Coomi Vevaina, University of Bombay, India Robert K. Whelan, University of New Orleans, U.S.A. The International Journal of Canadian Paraissant deux fois l’an, la Revue Studies (IJCS) is published twice a year internationale d’études canadiennes by the International Council for (RIÉC) est publiée par le Conseil Canadian Studies. -

Download (7MB)

- "SMALL" TALK: THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF THE DIMINUTIVE SUFFIX IN NORTHERN EAST CREE by © Amanda Cunningham A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland May 11, 2008 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract Diminutivization is a morphological process that is commonly attested among the world's languages. Though it has been studied in numerous languages belonging to a variety of language families, there has been a limited amount of research conducted on the diminutive in Algonquian. This thesis examines the diminutive suffix in Northern East Cree (NEC), a subdialect of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi which is a Central Algonquian language spoken in Quebec. Comparisons, where possible, are made with other Algonquian dialects for which there is diminutive data. The phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic properties of the particle, nominal, and verbal diminutive in NEC are described. There is a particular focus on the verbal diminutive, the investigation of which analyzes its distribution by identifying what elements of the sentence (subject, object, and/or verb) it modifies within each of the four Algonquian verb classes. The extent to which the Algonquian diminutive behaves like inflectional morphology is also discussed. 11 Acknowledgments Completion of a project of this magnitude can never be achieved by just one individual. I owe my success to a number of people and organizations. First, and foremost, I must acknowledge the amazing team of faculty, administrative staff, and graduate students that comprise the Linguistics Department at MUN. -

Building a Community Language Development Team with Québec Naskapi Bill Jancewicz, Marguerite Mackenzie, George Guanish, Silas Nabinicaboo

Building a Community Language Development Team with Québec Naskapi Bill Jancewicz, Marguerite MacKenzie, George Guanish, Silas Nabinicaboo Although the Naskapi language has many features in common with other Algonquian languages spoken in northern Quebec, it is in a unique situation because of the Naskapi people’s relatively late date of European contact, their geographic isolation, and the fact that, within their territory, Naskapi speakers outnumber speakers of Canada’s official languages. Historically, the vernacular word from which we derive the modern term “Naskapi” was applied to people not yet influenced by European culture. Nowadays, however, it refers specifically to the most remote Indian groups of the Quebec-Labrador peninsula (Mailhot, 1986). The Naskapi of today, who now comprise the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach near Schefferville, are direct descendants of nomadic caribou hunters of the Ungava tundra region. Although they are sometimes considered a part of the larger Innu grouping (also referred to as Montagnais-Naskapi by linguists and anthropologists), the Naskapi themselves insist that they are a unique people-group. Indeed, it can be shown both linguistically and ethnographically that the Naskapi are distinct from their neighbours (Jancewicz, 1998). Although they do share many cultural and linguistic traits with the Labrador Innu, the Quebec Montagnais, and the East Cree, they also have a unique history and some distinct linguistic forms that set them apart. The Naskapi language has retained a core vocabulary not found in related languages or in neighbouring dialects, although the majority of the vocabulary and the pronunciation reflect the variety of their contacts with other language groups. -

A Bibliography of Salish Linguistics

A Bibliography of Salish Linguistics Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Northwest Journal of Linguistics 2.3 A Bibliography of Salish Linguistics Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Abstract This bibliography lists materials (books, articles, conference papers, etc.) on Salish linguistics. As such, it mainly contains grammars, dictionaries, text collections and analyses of individual topics, but it also lists anthropological studies, curriculum materials, text collections in translation, and general survey works that have a sufficiently large Salish linguistic content. Criteria for inclusion of items, and the general methodology for assembling a bibliography of this kind, are discussed in the introduction. The work concludes with a list of abbreviations and a language-based index. This bibliography should be of use to linguists, particularly Salishists, but also to anthropologists and curriculum developers. The bibliography is essentially a sequel to Pilling 1893 (listed in the bibliography), although a number of items listed in that older source are also included here. KEYWORDS: Salish languages and dialects; Salish language family; bibliography; language index Northwest Journal of Linguistics 2.3:1–128 (2008) Table of Contents Introduction 4 Restrictions and criteria 5 General principles 8 The Salish conferences 9 Caveats and disclaimer 9 Salish languages and dialects 10 Bibliography of Salish Linguistics 13 Abbreviations 116 Appendix: Language Index 118 Northwest Journal of Linguistics 2.3:1–128 (2008) A Bibliography of Salish Linguistics Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Introduction. The following is a selected bibliography of those books and articles that deal with the description and analysis of Salish languages. -

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh 37th Algonquian Conference, Ottawa 2005 Bill Jancewicz SIL International and Naskapi Development Corporation ABSTRACT Submitted as an update to a presentation made at the 34th Algonquian Conference (Kingston). The ongoing development of the operating systems has included increased support for cross-platform use of Unicode syllabic script. Key improvements that were included in Macintosh's OS X.3 (Panther) operating system now allow direct keyboarding of Unicode characters by means of a user-defined input method. A summary and comparison of the available tools for handling Unicode on both Windows and Macintosh will be discussed. INTRODUCTION Since 1988 the author has been working in the Naskapi language at Kawawachikamach with the primary purpose of linguistic analysis and Bible translation, sponsored by Wycliffe Bible Translators and SIL International. Related work includes mother tongue translator training, Naskapi literature and curriculum development. Along with the language work the author also developed methods of production for Naskapi language materials in syllabic script by means of the computer. With the advent of high quality publishing capabilities in newer computers, procedures were updated to keep pace with the improving technology. With resources available from SIL International computer services department, a very satisfactory system of keyboarding syllabic texts in Naskapi was developed. At the urging of colleagues working in related languages, the system was expanded to include the wider inventory of standard Eastern and Western Cree syllabics. While this has pushed the limit of what is possible with the current technology, Unicode makes this practical. Note that the system originally developed for keyboarding Naskapi syllabics is similar but not identical to the Cree system, because of the unique local orthography in use at Kawawachikamach. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

Including Indigenous languages in education: An analysis of Canadian policy documents by Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft B.A. (Hons.), University of Alberta, 2012 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, education, satire, parody, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Cassidy Jasmine Foxcroft Degree: Master of Arts Title: Including Indigenous languages in education: An analysis of Canadian policy documents Examining Committee: Chair: Yue Wang Associate Professor John D. Mellow Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Suzanne Hilgendorf Supervisor Associate Professor Patricia Shaw External Examiner Professor Department of Anthropology University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: August 05, 2016 ii Abstract Language policy may promote or reduce the use and acquisition of languages. Indigenous languages in Canada are endangered and the number of speakers of these languages is declining. In this thesis, I examine a number of Canadian language policies in order to analyse whether provisions exist for including Indigenous languages within educational programmes. Previous studies of Canadian language policies have often only briefly addressed Indigenous languages. My analysis considers some of the policy documents discussed in earlier studies (e.g. the 1969 Official Languages Act), some recent policy documents (e.g.