Steve Abney CLD: Software for Analysis of Anishinaabemowin Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackfoot Language for the Morning Indigenous (Blackfoot) Language

LESSON PLAN Date:_____________________________ Blackfoot Language for the Morning Indigenous (Blackfoot) Language ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Origin Please read this Acknowledgement before the start of this lesson to respect the knowledge that is being shared and the Land of the People where the knowledge Kainai First Nation originates.: Alberta The original signatories for The Articles of Treaty 7 include the Blackfoot, Blood, Peigan, Sarcee, and Stoney nations as well as Her Majesty the Queen of England on Learning Level / Grade behalf of Canada. Treaty 7 was signed on September 22, 1877. This document describes the expansive lands exchanged for benefits promised into perpetuity to the descendants of the signatories which include health care, schools and reserved land. Beginner The Treaty is a living document, all people living in Treaty 7 territory are treaty members bound with mutual responsibilities to support peaceful co-existence. Language LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of this lesson plan, students will be able to: 130 mins 1. Share factual information by describing series or sequences of events or actions (in this case, his/her morning routine). [A-1, A-1.1] 2. Use the language creatively, for imaginative purposes and personal enjoyment Cross-Curricular and for creative/aesthetic purposes by creating a picture story with captions. (Related) Subjects [A-6, A-6.2] 3. Attend to the form of the language with simple sentences using I, you, Indigenous Ways of Knowing he/she, and subjects and action words in declarative statements. [LC-1 [1S, 2S, & Being 3S, VAI]] 4. Form positive relationships with others; e.g., peers, family, and Elders. -

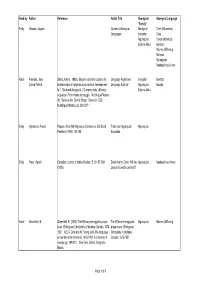

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Sustaining Indigenous Languages Looking Back, Looking Forward Inge Genee and Conor Snoek

Sustaining Indigenous Languages Looking Back, Looking Forward Inge Genee and Conor Snoek In the past decade or so, the endangerment of many of the world’s Indigenous and other minority languages has begun to percolate into the public consciousness, becoming part of the wider debate about cultural, environmental, and economic sustainability. The United Nations declaration of 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages (en.iyil2019.org) can be considered emblematic of the rise in global awareness of the threat of language extinction. Popular press articles about language endangerment are becoming more common, and local papers often comment on initiatives to revitalize or maintain Indigenous languages of a specific group or territory. In addition, social media groups promote and support individual language communities and provide a means of connecting speakers living outside their communities of origin. It is becoming clearer all the time that language maintenance has many benefits in addition to the preservation of unique ways of seeing the world, including mental and physical health benefits (Biddle and Swee 2012; Hallett et al. 2007; Whalen et al. 2016), community benefits (Romero-Little et al. 2011) and educational benefits (Huffmann 2018; Luning and Yamaguchi 2010; Reyhner 2017). Indigenous language communities and linguists working in Indigenous language documentation and related fields have been aware of the threat to In- digenous languages for several decades. Passionate writings calling the linguistic community to action emerged as early as the 1990s (Crawford 1998; Grenoble and Whaley 1998; Hinton 1997; Krauss 1992), but, like the climate scientists who long warned of a looming crisis, linguists and language activists have struggled to be heard. -

Language Data Tables User Guide

Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous Communities in Canada Language Data Tables User Guide Version 0.7.1 Norris Research Inc. https://norrisresearch.com/ref_tables.htm 1 January 2021 Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Recommended Citation: Norris Research Inc. (2020). Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous communities in Canada: Language Data Tables Users Guide, 01 January 2021. Draft Report prepared under contract with the Department of Canadian Heritage. Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 !! IMPORTANT !! ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Cautionary Note ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 Website Tips and Tricks ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tree View ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

North Fork Town

North Pork Town NORTH FORK TOWN By Carolyn Thomas Foreman North Fork Town was a well known settlement in the Indian Territory before the building of the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Rail- road in 1872. A number of prominent men made the place their home; it was the seat of one of the most useful missions amoug the Creeks; the mercantile establishments there were well stocked and prosperous. Among the Creeks who emigrated in 1829 to the West was John Davis, a full-blood who had been a pupil of the Reverend Lee Com- pere. When a boy Davis was taken prisoner in the War of 1812, and reared by a white man. Educated at Union Mission after coming to the Indian Territ.ory, be was appointed as a missionary by the Bap- tist Board in 1830. After Davis was ordained October 20, 1833, he assisted the Reverend David Rollin in establishing schools; hls preaching was said to have been productive of much good. He fre- quently acted as interpreter, and he worked at Shawnee Mission with Johnston Lykins in the preparation of Creek books. Jotham Meeker noted the arrival of Davis and the Reverend Saaipson Burch, a Choctaw from Red River, at Shawanoe on May 2, 1835. They had come at the invitation of Lykins to print some matter on the new system originated there by Meeker. They re- mained at the mission about three months; Davis compiled a school book in Creek and translated into that language the Gospel of John. On May 5 Meeker, assisted by Davis, began forming the Creek alphabet; four days later Davis took his manuscript to the press and on the eleventh Meeker and Davis revised it. -

By TRUMAN MICHELSON

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology BuUetin 123 Anthropological Papers, No. 8 Linguistic Classification of Cree and Montagnais-Naskapi Dialects By TRUMAN MICHELSON 67 LINGUISTIC CLASSIFICATION OF CREE AND MONTAGNAIS-NASKAPI DIALECTS By Truman Michelson In 1912 I had an opportunity to study the Cree of Fort Totten (North Dakota), and in 1920 had a chance to study the Cree of Files Hill, Saskatchewan, Canada. In 1923 I observed the Montagnais of Lake St. John and Lake Mistassini at Pointe Bleu, Quebec. In 1924 at the Northwest River I studied the dialect of Davis Inlet from an Indian there, and gained a little knowledge of the dialect of the Northwest River. The American Council of Learned Societies made it possible for me in the summer and early fall of 1935 to do field- work among some of the Algonquian Indians in the vicinity of James and Hudson's Bay. I visited Moose Factory, Rupert's House, Fort George, and the Great Whale River. However, I was able to do a little work on the Albany Cree and Ojibwa owing to their presence at Moose Factory; and I did a few minutes work with an East Main Indian whom I stumbled across at Rupert's House; similarly I worked for a few minutes on the Weenusk dialect as an Indian from there chanced to come to Moosonee at the foot of James Bay. Owing to a grant-in-aid made by the American Coun- cil of Learned Societies it was possible for me to again visit the James and Hudson's Bays region in the spring, summer, and early fall of 1936. -

Article Title

Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri Stabilizing Indigenous Languages 1 Symposium Report Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri* A note from Pat Kelley, SIL International Literacy Coordinator Few of our field practitioners are strategically located for attending some of the conferences around the world that may be related to the work we do in literacy. Also, in many cases, especially if no paper is being presented, there may be limited funds available for transportation. Yet there is much to be learned from such conferences: for example, vocabulary and new terminology, current trends, what’s “out there” in the prominent theory and practice of related fields applicable to our work, current research, issues defined by the “voices” for literacy, etc. For that reason, when our SIL literacy personnel and national colleagues do attend or present at a conference, on occasion we’ll include a “Conference Report” … so that our field personnel may glean information from them. When possible, contact details will be provided in order to request additional information. These reports will reflect the growing trend in the Literacy domain for copresenting and coauthoring, which hopefully will continue as we determine to see capacity building in this area among our national colleagues. Dennis Malone (SIL International in Bangkok, Thailand), and Isara Choosri (Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development at Mahidol University at Salaya, Thailand) coauthor this report of the Ninth Annual Symposium on Stabilizing Indigenous • Dennis Malone ([email protected]) is an International Literacy Consultant, serving with his wife Susan in the Asia Area. He is involved in minority language education projects in the Asia Area and also serves as a guest lecturer at the ILCRD. -

Table of Contents

August-September 2015 Edition 4 _____________________________________________________________________________________ We’re excited to share the positive work of tribal nations and communities, Native families and organizations, and the Administration that empowers our youth to thrive. In partnership with the My Brother’s Keeper, Generation Indigenous (“Gen-I”), and First Kids 1st Initiatives, please join our First Kids 1st community and share your stories and best practices that are creating a positive impact for Native youth. To highlight your stories in future newsletters, send your information to [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Youth Highlights II. Upcoming Opportunities & Announcements III. Call for Future Content *************************************************************************************************** 1 th Sault Ste. Marie Celebrates Youth Council’s 20 Anniversary On September 18 and 19, the Sault Ste. Marie Tribal Youth Council (TYC) 20-Year Anniversary Mini Conference & Celebration was held at the Kewadin Casino & Convention Center. It was a huge success with approximately 40 youth attending from across the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians service area. For the past 20 years, tribal youth grades 8-12 have taken on Childhood Obesity, Suicide and Bullying Prevention, Drug Abuse, and Domestic Violence in their communities. The Youth Council has produced PSAs, workshops, and presentations that have been done on local, tribal, state, and national levels and also hold the annual Bike the Sites event, a 47-mile bicycle ride to raise awareness on Childhood Obesity and its effects. TYC alumni provided testimony on their experiences with the youth council and how TYC has helped them in their walk in life. The celebration continued during the evening with approximately 100 community members expressing their support during the potluck feast and drum social held at the Sault Tribe’s Culture Building. -

Aboriginal Languages and Selected Vitality Indicators in 2011

Catalogue no. 89-655-X— No. 001 ISBN 978-1-100-24855-4 Aboriginal Languages and Selected Vitality Indicators in 2011 by Stéphanie Langlois and Annie Turner Release date: October 16, 2014 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected], telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following toll-free numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 To access this product This product, Catalogue no. 89-655-X, is available free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca, and browse by “Key resource” > “Publications.” Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has developed standards of service that its employees observe. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “About us” > “The agency” > “Providing services to Canadians.” Standard symbols Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada The following symbols are used in Statistics Canada publications: . -

Near the Edge: Language Revival from the Brink of Extinction

NEAR THE EDGE: LANGUAGE REVIVAL FROM THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION James Rementer, Language Director The Delaware Tribe, Bartlesville, Oklahoma and Bruce L. Pearson, University of South Carolina 1. Introduction. The authors have spent close to forty years, individually and often collaboratively, working on three Native American languages. Our experiences are fairly typical of people who become involved in Indian languages, whether they are born into a tribal community or come as outsiders. The three languages are Delaware and Shawnee, both Algonquian, and Wyandotte, and Iroquoian language. Although the focus of this conference is on Algonquian languages, the threat of extinction is common to all native languages regardless of family identity. These three languages themselves represent different stages common to threatened languages and typical responses within threatened language communities. The last speaker of Wyandotte died some 50 years ago. Delaware now has but one living native speaker, an elderly man whose health no longer permits him to actively pass on the language. The language is preserved by a few adults who have acquired limited fluency in recent years. Only Shawnee has native speakers still living although all are above age fifty. The attitudes toward language revival and the programs adopted to preserve the language differ in each community. These differences are based largely on the perceived degree of endangerment and community assumptions about what can be done to preserve the language and, more importantly, what should be done. We will describe the situation in these three communities starting with the one in which we have had the longest and most extensive involvement and proceeding to those in which we have had a lesser degree of involvement.