Building a Community Language Development Team with Quebec Naskapi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

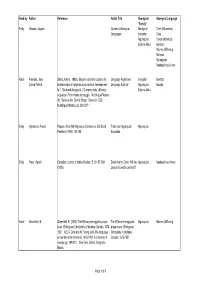

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

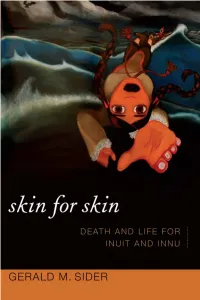

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C). -

3. Naskapi Women: Words, Narratives, and Knowledge

chapter three Naskapi Women Words, Narratives, and Knowledge Carole Lévesque, Denise Geoffroy, and Geneviève Polèse By sharing their stories and knowledge, Naskapi women have played a key role in the reconstruction of the cultural and ecological heritage of their people. The Naskapi, who live in the subarctic region of the province of Québec, today represent about nine hundred people, most of whom reside in the village of Kawawachikamach, located about fifteen kilometres from the former mining town of Schefferville, along the 55th parallel (see map 3.1). The first written reports of the Naskapi date from the late eighteenth century. It appears that, at the time of the Europeans’ arrival, the peoples to whom these reports refer did not form a single, integrated group rather they were several groups of hunters who ranged across the northern portion of the Québec Labrador peninsula (Lévesque, Rains, and de Juriew 2001). The evidence suggests that these were families or groups of hunters of Innu origin who, sometime around the mid-eighteenth century, had apparently migrated to the hinterland of the subarctic region from the North Shore of the St. Lawrence (where several Innu bands had settled). Initially few in number, the Naskapi are said to have comprised about three hundred people around 1830 (Lévesque et al. 2001). 59 doi:10.15215/aupress/9781771990417.01 Ungava Bay Québec Fort Chimo Fort McKenzie Kawawachikamach Newfoundland and Labrador Québec Map 3.1 Location of the Naskapi village of Kawawachikamach, northern Québec. Source: Laboratoire d’analyse spatiale et d’économie urbaine et régionale, Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Montréal. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

1 Exhibits from the Taylor Collection Acquired July 2004 Appendix a 1

Exhibits from The Taylor Collection acquired July 2004 Appendix A 1. Callendar Collection Collected by the Rev. and Mrs Callendar in Makkovik, Labrador between 1919 and 1921, acquired by Colin Taylor from their son Alan in St. Leonards in 1975 Pair of snow goggles (similar to those worn by Grey Owl to avoid snow blindness) and hard tack dog biscuits, Taylor cat.314 2 summer coats from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.152 1 winter coat from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. 60 Carved figure of Inuit woman with child in hood Taylor cat.58 Ceremonial embroidered moccasins from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.42 Valance decorated with floral embroidery on black velvet probably from the Athabaskan Indians of the Sub-Artic Taylor cat.294 Wooden carvings of animals: 2 bears,1 dog, 1 arctic fox ( leg missing ) Taylor cat. 175 Hide working tools: stretcher and scraper Taylor cat.69 Model in bone of dog sledge and man Taylor cat. 73 Sewing kit in sealskin holder containing awls, hook and marking knife, Labrador Eskimo, Taylor cat. 70a Sealskin wall pouch (Inuit) Taylor cat. 74 Model snow shoes, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 3 Child’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 25 1 Taylor Collection List of Exhibits Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 62 Child’s single embroidered moccasin, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 234 Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 143ii Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais, Taylor cat. 143i Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Taylor cat.202b Beaded pouch from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. -

Cree-Naskapi (Of Quebec) Act Loi Sur Les Cris Et Les Naskapis Du Québec

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act Loi sur les Cris et les Naskapis du Québec S.C. 1984, c. 18 S.C. 1984, ch. 18 Current to November 9, 2016 À jour au 9 novembre 2016 Last amended on May 15, 2014 Dernière modification le 15 mai 2014 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (2) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (2) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

Eastern Woodland Indian Tribes

Eastern Woodland Indian Tribes Tribes of the Eastern Woodlands *Abenaki Tribe *Algonquin Tribe *Cayuga Tribe *Chippewa Tribe *Huron/Wyandot Tribe *Illinois Tribe *Iroquois Tribe *Kickapoo Tribe *Lenape Tribe *Lumbee Tribe *Maliseet Tribe *Menominee Tribe *Miami Tribe *Micmac Tribe *Mohawk Tribe *Mohegan Tribe *Mohican Tribe *Montauk Tribe *Munsee Tribe *Nanticoke Tribe *Narragansett Tribe Family letter *Niantic Tribe *Nipmuc Tribe “The Indians of our tribe were the Oneidas-at one time they adopted another tribe. It could *Nottoway Tribe have been the Ojibwa’s.” In a letter written to Dora Green Steinhaus (pictured below on top right) by Elise *Oneida Tribe *Onondaga Tribe Hazen Green. (Pictured below on bottom right) *Ottawa Tribe *Passamaquoddy Tribe “Lucy Skeesuck was a Naragansett Indian. She was kicked off the reservation for *Penobscot Tribe *Pocomtuc Tribe marrying a white guy (Mr. Welch). Their daughter, Mary Ann Welch , was born on *Potawatomi Tribe the reservation of the Pequot tribe. Mary Ann’s daughter was Helen Cornelia Welch. *Powhatan Tribe *Quiripi/Quinnipiac Tribe She had a daughter, Dora Wilber. Dora had a daughter named Elsie Hazen. Elsie’s *Sac and Fox Tribe *Seneca Tribe eldest daughter you knew and loved as Nana. She was Dora Green Stienhaus” In an *Shawnee Tribe email from Barb Steinhaus, great aunt of Brienz Ottman. Written 2/5/15 *Susquehannock Tribe *Wampanoag Tribe *Wappinger Tribe *Winnebago/Hochunk Tribe Wigwams Wigwams are a typical home for the Eastern Woodlands. A wigwam is a dwelling first used by certain Native American and Canadian First Nations tribes. Now it is used for ceremonial purposes. Wigwams were mostly made of things found in the surrondings like sticks, grass, bark, and mud. -

Download (7MB)

- "SMALL" TALK: THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF THE DIMINUTIVE SUFFIX IN NORTHERN EAST CREE by © Amanda Cunningham A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland May 11, 2008 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract Diminutivization is a morphological process that is commonly attested among the world's languages. Though it has been studied in numerous languages belonging to a variety of language families, there has been a limited amount of research conducted on the diminutive in Algonquian. This thesis examines the diminutive suffix in Northern East Cree (NEC), a subdialect of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi which is a Central Algonquian language spoken in Quebec. Comparisons, where possible, are made with other Algonquian dialects for which there is diminutive data. The phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic properties of the particle, nominal, and verbal diminutive in NEC are described. There is a particular focus on the verbal diminutive, the investigation of which analyzes its distribution by identifying what elements of the sentence (subject, object, and/or verb) it modifies within each of the four Algonquian verb classes. The extent to which the Algonquian diminutive behaves like inflectional morphology is also discussed. 11 Acknowledgments Completion of a project of this magnitude can never be achieved by just one individual. I owe my success to a number of people and organizations. First, and foremost, I must acknowledge the amazing team of faculty, administrative staff, and graduate students that comprise the Linguistics Department at MUN.