3. Naskapi Women: Words, Narratives, and Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C). -

Continuation of the Negotiations with the Innu

QUEBECERS and the INNU CONTINUATION OF THE NEGOTIATIONS WITH THE INNU AGREEMENT-IN-PRINCIPLE WORKING TOGETHER TO ACHIEVE A TREATY Québec Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones Québec HOW TO PARTICIPATE IN THE NEGOTIATIONS The Government of Québec has put in place a participation mechanism that allows the populations of the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and Côte-Nord regions to make known their opinion at the negotiating table. Québec’s negotiations team includes a representative of the regions who attends all of the negotiation sessions. He is the regions’ spokesperson at the negotiating table. The representative of the regions can count on the assistance of one delegate in each of the regions in question. W HAT IS THE RO L E OF THE REP RES ENTATIV E O F THE REGIO NS AND THE DELEGATES? 1 To keep you informed of the progress made in the work of the negotiating table. 2 To consult you and obtain your comments. 3 To convey your proposals and concerns to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and to the special negotiator for the Government of Québec. WHAT IS THE AGREEM ENT-IN-P RINCIPLE? The agreement-in-principle reached by the Government of Québec, the Government of Canada and the First Nations of Betsiamites, Essipit, Mashteuiatsh and Nutashkuan will serve as a basis for negotiating a final agreement that will compromise a treaty and complementary agreements. In other words, it is a framework that will orient the pursuit of negotiations towards a treaty over the next two years. WHY NEGOTIATE? Quebecers and the Innu have lived together on the same territory for 400 years without ever deciding on the aboriginal rights of the Innu. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

Quebec, Le 12 Octobre 2010

Quebec, October 14, 2010 By fax only to 613-957-0941 Panel Manager Project Assessment Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only to 709-729-5693 Co-Manager Lower Churchill Joint Review Panel Secretariat 33 Pippy Place PO Box 8700 St. John's NL A1B 4J6 By fax only to 613- 957-0935 Daniel Martineau Aboriginal Consultation Coordinator 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only to 709-737-1859 Todd Burlingame Nalcor Energy, Lower Churchill Project 500 Columbus Drive PO Box 12800 St. John's NL A1B 0C9 Subject: Correction regarding the Unamen Shipu Innu’s comments on the proponent, Nalcor Energy’s consultation report (Nalcor’s 2010 Consultation Assessment Report) in response to file IR# JRP.151. Maryse Pineau, Tom Graham, Daniel Martineau, Todd Burlingame: Please note there is an error in the sent version of the Unamun Shipu Innu’s comments regarding the proponent, Nalco Energy’s consultation report (Nalcor’s 2010 Consultation Assessment Report) in response to file IR# JRP.151. LITIGANTS & ADVISORS 1379 chemin Ste-Foy, Suite 210, Quebec QC G1S 2N2 Telephone: 418-527-9009 Fax: 418-527-9199 Box 199 Item 5 of our comments, titled FILE UPDATE, should read October 21, 2010 instead of October 15, 2010. Sincerely, GAUCHER LEVESQUE TABET (François Levesque) Counsel for the Unamen Shipu Innu Quebec City, October 12, 2010 By fax only 613-957-0941 Panel Manager Project Assessment Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only 709-729-5693 Co-Manager Lower Churchill Joint Review Panel Secretariat 33 Pippy Place PO Box 8700 St. -

Migration: a Way of Life for the Innu Newfoundland - Secondary

MIGRATION: A WAY OF LIFE FOR THE INNU NEWFOUNDLAND - SECONDARY Migration: A Way of life for the Innu of Labrador for Thousands of Years Lesson Overview: This lesson is to introduce students to the idea of migration by integrating the link between migration and Canada’s Aboriginal peoples. In this case, students will be studying the Innu People of Quebec and Labrador. The Innu have been living in Quebec and Labrador for thousands of years and have migrated over their land for all of that time. Today, migrations still occur but it is not like it was in the “old” days. Most of the Innu today live seasonally in the country and reside in communities in Quebec and in two communities: Sheshatshiu (Shet a Shee) and Natuashish (Nat wa Shish) in Labrador for the remainder of the year. Grade Level: Grades 9-12 Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island Grade 9 Social Studies, “Atlantic Canada in the Global Community” Newfoundland and Labrador, Grade 10-12: Canadian Geography, and World Geography. Time Required: This lesson can be completed in two one-hour periods. One class should be used for outlining the subject matter: giving the definitions, exploring the geographic area through maps, and discussion. In the second class, students should move to a computer lab and look at the website that supports the Innu culture and deals with family migrations. The link students should go to for this lesson is: http://www.innustories.ca/1300_e.php The website is called “tipatshimuna” which in Innu-Aimum (the language spoke by most Innu today) means stories. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

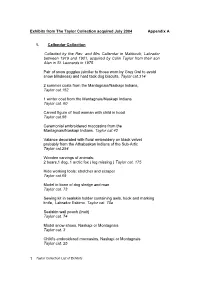

1 Exhibits from the Taylor Collection Acquired July 2004 Appendix a 1

Exhibits from The Taylor Collection acquired July 2004 Appendix A 1. Callendar Collection Collected by the Rev. and Mrs Callendar in Makkovik, Labrador between 1919 and 1921, acquired by Colin Taylor from their son Alan in St. Leonards in 1975 Pair of snow goggles (similar to those worn by Grey Owl to avoid snow blindness) and hard tack dog biscuits, Taylor cat.314 2 summer coats from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.152 1 winter coat from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. 60 Carved figure of Inuit woman with child in hood Taylor cat.58 Ceremonial embroidered moccasins from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.42 Valance decorated with floral embroidery on black velvet probably from the Athabaskan Indians of the Sub-Artic Taylor cat.294 Wooden carvings of animals: 2 bears,1 dog, 1 arctic fox ( leg missing ) Taylor cat. 175 Hide working tools: stretcher and scraper Taylor cat.69 Model in bone of dog sledge and man Taylor cat. 73 Sewing kit in sealskin holder containing awls, hook and marking knife, Labrador Eskimo, Taylor cat. 70a Sealskin wall pouch (Inuit) Taylor cat. 74 Model snow shoes, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 3 Child’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 25 1 Taylor Collection List of Exhibits Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 62 Child’s single embroidered moccasin, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 234 Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 143ii Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais, Taylor cat. 143i Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Taylor cat.202b Beaded pouch from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

His 4572 : Les Nations Amérindiennes Au Canada

Département d’histoire PLAN DE COURS HIS 4592-030 : Histoire des Autochtones du Canada (jusqu’au XIXe siècle) Session : automne 2019 Horaire : jeudi, 14h00 à 17h00 ; local : A-1730 Professeur : Fannie Dionne Bureau : A-6255 Courriel : [email protected] Disponibilités : jeudi, 12h30 à 14h00 (ou sur rendez-vous) A. Objectifs Ce cours retrace l’histoire des nations autochtones au Canada depuis le premier peuplement de l’Amérique, avec une insistance particulière sur la période qui suit les premiers contacts avec les Européens, au XVIe siècle. D’une manière plus précise, ce cours vise cinq objectifs : • l’acquisition d’une bonne connaissance des grandes caractéristiques des sociétés autochtones (aires culturelles, activités de subsistance, organisation sociale, structures politiques, pratiques et croyances religieuses…) • l’acquisition d’une bonne connaissance du cadre événementiel de l’histoire des nations autochtones, du peuplement initial de l’Amérique jusqu’au déclin des alliances avec les Européens au début du XIXe siècle ; • l’acquisition d’une bonne connaissance des grandes mutations survenues dans l’histoire des nations autochtones et des facteurs qui sont à l’œuvre dans ces changements (développement du commerce des fourrures, expansion coloniale, épidémies, entreprise missionnaire…) ; • la familiarisation avec certaines sources qui permettent de reconstituer l’histoire des sociétés autochtones et avec les problèmes d’interprétation que présentent ces documents ; • le développement d’un esprit d’analyse et de synthèse dans l’étude de problèmes historiques se rapportant aux sociétés autochtones. B. Formule pédagogique Exposés magistraux, conférences, analyse de documents historiques, film, visites et activités, ateliers. C. Calendrier et aperçu des thèmes 1. 5 septembre • Présentation du cours • Terminologie 2. -

Nunavut, a Creation Story. the Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2019 Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory Holly Ann Dobbins Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dobbins, Holly Ann, "Nunavut, A Creation Story. The Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory" (2019). Dissertations - ALL. 1097. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1097 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This is a qualitative study of the 30-year land claim negotiation process (1963-1993) through which the Inuit of Nunavut transformed themselves from being a marginalized population with few recognized rights in Canada to becoming the overwhelmingly dominant voice in a territorial government, with strong rights over their own lands and waters. In this study I view this negotiation process and all of the activities that supported it as part of a larger Inuit Movement and argue that it meets the criteria for a social movement. This study bridges several social sciences disciplines, including newly emerging areas of study in social movements, conflict resolution, and Indigenous studies, and offers important lessons about the conditions for a successful mobilization for Indigenous rights in other states. In this research I examine the extent to which Inuit values and worldviews directly informed movement emergence and continuity, leadership development and, to some extent, negotiation strategies.