Nunavut, a Creation Story. the Inuit Movement in Canada's Newest Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

– Annual Report Languages Commissioner of Nunavut – Rapport Annuel La Commis

ᐅᖃᐅᓯᓕᕆᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐊᒡᓚᒡᕕᒃ ᓄᓇᕗᒥ – Annual Report Languages Commissioner of Nunavut – Rapport Annuel La Commissaire aux langues du Nunavut | >> Page 3 © Office of the Languages Commissioner of Nunavut, --- © Bureau du Commissaire aux langues du Nunavut, --- The Honourable Kevin O’Brien L’honorable Kevin O’Brien Speaker of the House Président de la Chambre Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative Iqaluit, Nunavut Iqaluit (Nunavut) Mr. Speaker: Monsieur le Président, Pursuant to Section of the Offıcial Au titre de l’article de la Loi sur Languages Act, I hereby submit to the les langues offıcielles, je soumets par les Legislative Assembly for consideration, the présentes, pour considération par l’Assemblée annual report of the Languages Commissioner législative, le rapport annuel du Commissaire of Nunavut covering the period from April , aux langues du Nunavut, pour l’année fiscale to March , . –. Yours respectfully, Je vous prie de recevoir, l’expression de mes sentiments les plus distingués. Eva Aariak Languages Commissioner Eva Aariak Commissaire aux langues - The logo of the Office of the Languages Com- Le sigle du Bureau du Commissaire aux langues missioner of Nunavut consists of a single purple du Nunavut comporte une seule fleur de saxifrage flower,aupilaktunnguat in Inuktitut, saxifrage bleu, appelée aupilaktunnguat en protected by the qilaut, the Inuit drum. inuktitut, protégée par le qilaut, le tambour inuit As the official flower of Nunavut,aupilak - traditionnel. tunnguat represents all Nunavummiut regard- La fleur officielle du Nunavut, less of their ethnic background or mother aupilaktunnguat, se veut à l’image de tous les tongue. Blossoming in Nunavut’s rocky soil, Nunavummiut, quelles que soient leur langue this small plant signifies strength, endurance maternelle et leurs origines ethniques. -

H a Guide to Sport Fishing in Nunavut

h a guide to sport fishing in nunavut SPORT FISHING GUIDE / NUNAVUT TOURISM / NUNAVUTTOURISM.COM / 1.866.NUNAVUT 1 PLUMMER’S ARCTIC LODGES PLUMMER’S Fly into an untouched, unspoiled landscape for the adventure of a lifetime. Fish for record-size lake trout and pike in the treeless but colourful barrenlands. Try for arctic grayling in our cold clear waters. And, of course, set your sights on an arctic char on the Tree River, the Coppermine River, or dozens of other rivers across Nunavut that flow to the Arctic seas. Spend a full 24 hours angling for the species of your choice under the rays of the midnight sun. PLUMMER’S ARCTIC LODGES PLUMMER’S Pristine, teeming with trophy fish, rare wildlife and Read on to explore more about this remarkable place: nature at its rawest, Nunavut is a cut above any ordinary about the Inuit and their 1000-year history of fishing in sport fishing destination. Brave the stark but stunning one of the toughest climates in the world; about the wilderness of the region. Rise to the unique challenges experienced guides and outfitters ready to make your of Nunavut. And come back with jaw-dropping trophy- adventure run smoothly. Read on to discover your next sized catches, as well as memories and stories that great sport fishing experience! you’ll never tire of. Welcome To Sport Fishing Paradise. 2 SPORT FISHING GUIDE / NUNAVUT TOURISM / NUNAVUTTOURISM.COM / 1.866.NUNAVUT PLUMMER’S ARCTIC LODGES PRIZE OF THE ARCTIC Arctic Char The arctic char is on every sport fisher’s bucket list. -

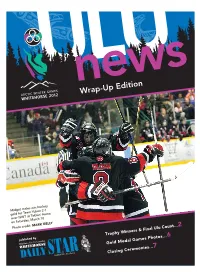

Wrap-Up Edition

Wrap-Up Edition Midget males win hockey gold for Team Yukon 2-1 over NWT at Takhini Arena on Saturday, March 10 Photo credit: MARK KELLY published by Trophy Winners & Final Ulu Count...2 Gold Medal Games Photos...6 Closing Ceremonies...7 2 ULU News Wednesday, March 14, 2012 • Whitehorse 2012 Arctic Winter Games WINNERS & TROPHIES Chef de Mission Jeffrey Seeteenak of Nunavut accepts the coveted Hodgson Trophy from Gerry Thick, AWG Interna- tional Committee President, at the closing ceremonies on AWG ULU COUNT Saturday, March 10 (Photo by Bruce Barrett) Final count TEAM NUNAVUT CONTINGENT TOTAL •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• TAKES HOME Alaska 61 67 62 190 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• HODGSON TROPHY Yukon 46 47 29 122 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• At each Arctic Winter Games, the AWG International NWT 32 30 54 116 Committee presents the Hodgson Trophy to the contingent •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• whose athletes best exemplify the ideals of fair play and Alberta team spirit. North 40 37 27 104 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• The Hodgson Trophy is on display at the Sport Yukon Hall of Fame in -

Nunavut Impzem 1 Ntation Commission

Nunavut ImpZem1 ntation Commission 1&hy by: JLC ~epro~r iC In: 1997 Reports of the Nun a vut lmplemen tation Commission June 30, 1998 Table of Contents 1. The Future of Work in Nunavut Conference: Final Report March 3-5, 1997, lqaluit June 30,1997 2. Integrating Inuit Rights and Public Law in Nunavut: a Draft Nunavut Wildlife Act October 17,1997 THE FUTURE OF WORK IN NUNAVUT CONFERENCE 3 - 5 March 1997 lqaluit This document is also available in French, lnuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, as well as in multiple formats: large print, audio cassette, braille and computer diskette. ISBN 1-896548-24-5 0~4~L<LL\cnPYC Nunavut Hivumukpalianikhaagut Katimayit Nunavut lmplementation Commission Commission d'etablissement du Nunavut June 30, 1997 To the Reader The creation of Nunavut is the result of 25 years of effort by the people of Nunavut to regain control of their destiny. The people of Nunavut will have come a long way in a very short period of time. April 1,I 999 represents a major milestone on the long hard road to self-determination. It also marks the beginning of the real work that remains to be done - the daily challenge of improving the quality of life in the communities. In preparation for the post-1999 period, the Nunavut lmplementation Commission has begun to shift its focus from designing the Nunavut Government to addressing social and economic policy issues. A government administrative structure is an empty shell without a social and economic agenda to guide it. The Future of Work in Nunavut Conference succeeded in putting us back in touch with our common goals. -

Canadian Arctic 1987

Canadian Arctic 1987 TED WHALLEY Ellesmere Island has, at Cape Columbia, the northern-most land in the world, at latitude about 83.1°. It is a very mountainous island, particularly on the north west and the east sides, and its mountains almost reach the north coast - the northern-most mountains in the world. It was from here that most of the attempts to reach the North Pole have started, including that of Peary - reputedly, but perhaps not actually, the first man to reach the Pole. Nowadays, tourist flights to the Pole by Twin Otter from Resolute Bay are common, but are somewhat expensive. The topography of Ellesmere is dominated by several large and small ice-caps which almost bury the mountains, and only the Agassiz Ice-Cap, which is immediately west of Kane Basin, has a name. On the north-west side there are two large and unnamed ice-caps, the larger of which straddles 82°N and the smaller straddles 8I.5°N. There is also a large unnamed ice-cap immediately west of Smith Sound, a smaller one on the south-east tip of Ellesmere Island, and another north of the settlement of Grise Fiord on the south coast. The north coast of Ellesmere was the home of great ice shelves, but, at about the turn of the century, the ice shelves started to break off and float away as so-called 'ice islands' that circulated for many decades around the arctic ocean, and still do. They have often been used as natural platforms for scientific expeditions. Perhaps nine-tenths of the original ice shelves have floated away. -

Short Title Changes in Surface Height, 1957-1967, Of

SHORT TITLE CHANGES IN SURFACE HEIGHT, 1957-1967, OF THE GILMAN GLACIER Keith Charles Arnold, Facu1ty of Graduate Studies, Interdiscip1inary G1acio1ogy, for degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Keith Charles Arnold Determination of Changes of Surface Height, 1957 to 1967, of the Gi1man Glacier, Northern Ellesmere Island, Canada. Facu1ty of Graduate Studies Interdiscip1inary G1acio10gy Master of Science SUMMARY In 1967, 29 points on the Gi1man Glacier origina11y 10cated in 1957 were repositioned with a mean error of 0.36 m. Their height were redetermined with a mean error of 0.25 m. Refraction coefficients ranged from 0.047 to 0.558, with a mean of 0.162. A profile in the accumulation area showed 1itt1e change. Down glacier from a seismic profile near the average position of the equi1ibrium 1ine, 1957 to 1967, the average height 10ss was 2.4 m. From May 1958 to May 1967 the glacier advanced 25.4 m. A volume 10ss ca1cu1ated from height 10ss and glacier advance was 165 x 106 m3 , compared with 140 x 106 m3 ca1cu1ated from mass balance data, part1y estimated for missing years, and glacier f10w through the seismic profile. This area had a negative mass balance of 91 cm ice/yr; 69 cm ice/yr wou1d balance the vertical component of f10w, keeping the surface unchanged. DETERMINATION OF CHANGES OF SURFACE HEIGHT, 1957-1967, OF THE GILMAN GLACIER, NORTHERN ELLESMERE ISLAND, CANADA K. C. Arnold A thesis submitted in accordance with the regu1ations for the degree of Master of Science at McGi11 University. 1968 1 ® K.C. Arnold 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Debates of the Senate

Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 41st PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 149 . NUMBER 35 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, February 12, 2014 The Honourable NOËL A. KINSELLA Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: David Reeves, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 936 THE SENATE Wednesday, February 12, 2014 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. Many got involved in the Canadian parliamentary system by working for or sitting as members of the two houses. I'm thinking Prayers. of Senator Pascal Poirier and Senator Calixte Savoie, not to mention the Right Honourable Roméo LeBlanc, who, after sitting [Translation] as a member of the other place and becoming the Speaker of this honourable chamber, rose to the highest office in Canada, that of Governor General. SENATORS' STATEMENTS No doubt senators are familiar with another alumnus of the college, Arthur Beauchesne, a former clerk in the other place and the author of the annotated Rules and Forms of the House of COLLÈGE SAINT-JOSEPH Commons of Canada, who attended Université Saint-Joseph before studying law in Montreal. ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY Honourable senators, please join me in congratulating and Hon. Fernand Robichaud: Honourable senators, I wish to draw thanking the founders of Collège Saint-Joseph, who, 150 years your attention to the 150th anniversary of the founding of ago, laid the foundations for the institute of higher learning that Collège Saint-Joseph in Memramcook, New Brunswick. -

Statutory Report on Wildlife to the Nunavut Legislative Assembly Section 176 of the Wildlife Act

Statutory Report on Wildlife to the Nunavut Legislative Assembly Section 176 of the Wildlife Act 1.0 Review of Wildlife and Habitat Management Programs for Terrestrial Species in Nunavut…………………………………………………………….1 1.1 Wildlife Act and Wildlife Regulations………………………………………………..2 1.2 Qikiqtaaluk Region……………………………………………………………………2 1.2.1 Qikiqtaaluk Research Initiatives…………………………………………………….2 a. Peary caribou………………………………………………………………………….2 b. High Arctic muskox…………………………………………………………………...3 c. North Baffin caribou…………………………………………………………………..4 1.2.2 Qikiqtaaluk Management Initiatives………………………………………………...5 a. Peary Caribou Management Plan……………………………………………………...5 b. High Arctic Muskox…………………………………………………………………..5 c. South Baffin Management Plan……………………………………………………….6 1.3 Kitikmeot Region……………………………………………………………………...8 1.3.1 Kitikmeot Research Initiatives………………………………………………………9 a. Wolverine and Grizzly bear Hair Snagging………………………………………….. 9 b. Mainland Caribou Projects……………………………………………………………9 c. Boothia Caribou Project……………………………………………………………...10 d. Dolphin and Union Caribou Project……………………............................................10 e. Mainland and Boothia Peninsula Muskoxen………………………………………...11 f. Harvest and Ecological Research Operational System (HEROS)…………………...12 g. Vegetation Mapping……………………………………………………………….....12 1.3.2 Kitikmeot Management Initiatives…………………………………………………12 a. Grizzly Bear Management…………………………………………………………...12 b. Bluenose East Management Plan…………………………………………………….12 c. DU Caribou Management Plan………………………………………………………13 d. Muskox Status -

Aleuts: an Outline of the Ethnic History

i Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Roza G. Lyapunova Translated by Richard L. Bland ii As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has re- sponsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Shared Beringian Heritage Program at the National Park Service is an international program that rec- ognizes and celebrates the natural resources and cultural heritage shared by the United States and Russia on both sides of the Bering Strait. The program seeks local, national, and international participation in the preservation and understanding of natural resources and protected lands and works to sustain and protect the cultural traditions and subsistence lifestyle of the Native peoples of the Beringia region. Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Author: Roza G. Lyapunova English translation by Richard L. Bland 2017 ISBN-13: 978-0-9965837-1-8 This book’s publication and translations were funded by the National Park Service, Shared Beringian Heritage Program. The book is provided without charge by the National Park Service. To order additional copies, please contact the Shared Beringian Heritage Program ([email protected]). National Park Service Shared Beringian Heritage Program © The Russian text of Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History by Roza G. Lyapunova (Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka” leningradskoe otdelenie, 1987), was translated into English by Richard L. -

Montreal, Quebec May 31, 1976 Volume 62

MACKENZIE VALLEY PIPELINE INQUIRY IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATIONS BY EACH OF (a) CANADIAN ARCTIC GAS PIPELINE LIMITED FOR A RIGHT-OF-WAY THAT MIGHT BE GRANTED ACROSS CROWN LANDS WITHIN THE YUKON TERRITORY AND THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES, and (b) FOOTHILLS PIPE LINES LTD. FOR A RIGHT-OF-WAY THAT MIGHT BE GRANTED ACROSS CROWN LANDS WITHIN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES FOR THE PURPOSE OF A PROPOSED MACKENZIE VALLEY PIPELINE and IN THE MATTER OF THE SOCIAL, ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACT REGIONALLY OF THE CONSTRUCTION, OPERATION AND SUBSEQUENT ABANDONMENT OF THE ABOVE PROPOSED PIPELINE (Before the Honourable Mr. Justice Berger, Commissioner) Montreal, Quebec May 31, 1976 PROCEEDINGS AT COMMUNITY HEARING Volume 62 The 2003 electronic version prepared from the original transcripts by Allwest Reporting Ltd. Vancouver, B.C. V6B 3A7 Canada Ph: 604-683-4774 Fax: 604-683-9378 www.allwestbc.com APPEARANCES Mr. Ian G. Scott, Q.C. Mr. Ian Waddell, and Mr. Ian Roland for Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry Mr. Pierre Genest, Q.C. and Mr. Darryl Carter, for Canadian Arctic Gas Pipeline Lim- ited; Mr. Alan Hollingworth and Mr. John W. Lutes for Foothills Pipe- lines Ltd.; Mr. Russell Anthony and pro. Alastair Lucas for Canadian Arctic Resources Committee Mr. Glen Bell, for Northwest Territo- ries Indian Brotherhood, and Metis Association of the Northwest Territories. INDEX Page WITNESSES: Guy POIRIER 6883 John CIACCIA 6889 Pierre MORIN 6907 Chief Andrew DELISLE 6911 Jean-Paul PERRAS 6920 Rick PONTING 6931 John FRANKLIN 6947 EXHIBITS: C-509 Province of Quebec Chamber of Commerce - G. Poirier 6888 C-510 Submission by J. -

Taima'na Uqamaqattangitlutit, the Polar Bears Can Hear

Taima’na Uqamaqattangitlutit, The Polar Bears Can Hear Consequences of words and actions in the Central Arctic • JERRY: [First in Inuktitut] My name is Jerry Arqviq and I am from Gjoa Haven, Nunavut. My father was a polar bear hunter. I am a polar bear hunter, and I now I am teaching my son. I started hunting when I was 6 years old and I caught my first polar bear when I was 14 years old. • DARREN: My name is Darren Keith and I am the Senior Researcher for the Kitikmeot Heritage Society which is based in Cambridge Bay. Jerry and I would like to thank some people who made it possible for us to be here in Paris: Canadian North Airlines who sponsored a portion of Jerry’s travel, World Wildlife Fund Canada, the organizing committee of the 15th Inuit Studies Conference, and a special thanks to Professor Beatrice Collignon. DARREN: The area we will be discussing is the Nattilik area of the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut. For the Inuit of the central Arctic, who live in the communities of Gjoa Haven, Taloyoak and Kugaaruk, Nunavut polar bears have always been an essential part of an Inuit or Inuktitut way of life based on hunting animals. Our paper will discuss some aspects of the relationship between Inuit and polar bears, and the sensitivity of polar bears to the statements and actions of human beings. JERRY: [talks about his community and the continued importance of country food to the people including polar bears – explains picture of young people fishing at the weir at Iqalungmiut last year, as they do every year.] • DARREN: This paper draws mainly on interviews with Elders conducted during a project for the Gjoa Haven Hunters and Trappers Organization of Gjoa Haven Nunavut. -

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) Electronic Version Obtained from Table of Contents

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) Electronic Version obtained from http://www.gcc.ca/ Table of Contents Section Page Map of Territory..........................................................................................................................1 Philosophy of the Agreement...................................................................................................2 Section 1 : Definitions................................................................................................................13 Section 2 : Principal Provisions................................................................................................16 Section 3 : Eligibility ..................................................................................................................22 Section 4 : Preliminary Territorial Description.....................................................................40 Section 5 : Land Regime.............................................................................................................55 Section 6 : Land Selection - Inuit of Quebec,.........................................................................69 Section 7 : Land Regime Applicable to the Inuit..................................................................73 Section 8 : Technical Aspects....................................................................................................86 Section 9 : Local Government over Category IA Lands.......................................................121 Section 10 : Cree