Revitalization and Renewal in the Wendat Confederacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stadacona Circle / Park

Stadacona Circle / Park The question could be asked: Do we know why Fred B. and Ella Grinnell gave Stadacona Circle (on 11 th Avenue East between Ivory and Arthur) to the city of Spokane? Many people remember the park, but very few remember the name. “Some of Spokane’s first ‘suburban’ neighborhoods were those planned and developed in East Central Spokane, beginning as early as 1900….East Central Spokane is a term applied to a large residential and commercial area which is roughly bounded by Sprague Avenue to the north, Fourteenth Avenue to the south, Division Street to the west, and Havana Street to the east (the city limit). Numerous multiple-block subdivisions were platted within the large East Central area and were called ‘additions,’ such as Stadacona Park Addition indicated how public greenspace was used and it is now a part of Grant Park.” 1 In 1901 Stadacona Circle was given to the city of Spokane by Citizens National Bank and Fred B. and Ella Grinnell. Later it was known as Stadacona Park. In 1901 there were no homes yet built in this area. “In the ‘Report of the Board of Park Commissioners, 1891-1913,’ it was noted that Stadacona Circle was a nice little spot nicely planted with trees and shrubbery, making a small breathing spot for the neighborhood.…If the Park Commission in accepting this little park agreed to build and maintain the surrounding street, about 25 or 30 feet wide, it made, in our opinion, a bad bargain for the city. If there was no such agreement, what should be done would be best determined by conditions as to which we are not posted. -

Wendat Ethnophilology: How a Canadian Indigenous Nation Is Reviving Its Language Philology JOHANNES STOBBE Written Aesthetic Experience

Contents Volume 2 / 2016 Vol. Articles 2 FRANCESCO BENOZZO Origins of Human Language: 2016 Deductive Evidence for Speaking Australopithecus LOUIS-JACQUES DORAIS Wendat Ethnophilology: How a Canadian Indigenous Nation is Reviving its Language Philology JOHANNES STOBBE Written Aesthetic Experience. Philology as Recognition An International Journal MAHMOUD SALEM ELSHEIKH on the Evolution of Languages, Cultures and Texts The Arabic Sources of Rāzī’s Al-Manṣūrī fī ’ṭ-ṭibb MAURIZIO ASCARI Philology of Conceptualization: Geometry and the Secularization of the Early Modern Imagination KALEIGH JOY BANGOR Philological Investigations: Hannah Arendt’s Berichte on Eichmann in Jerusalem MIGUEL CASAS GÓMEZ From Philology to Linguistics: The Influence of Saussure in the Development of Semantics CARMEN VARO VARO Beyond the Opposites: Philological and Cognitive Aspects of Linguistic Polarization LORENZO MANTOVANI Philology and Toponymy. Commons, Place Names and Collective Memories in the Rural Landscape of Emilia Discussions ROMAIN JALABERT – FEDERICO TARRAGONI Philology Philologie et révolution Crossings SUMAN GUPTA Philology of the Contemporary World: On Storying the Financial Crisis Review Article EPHRAIM NISSAN Lexical Remarks Prompted by A Smyrneika Lexicon, a Trove for Contact Linguistics Reviews SUMAN GUPTA Philology and Global English Studies: Retracings (Maurizio Ascari) ALBERT DEROLEZ The Making and Meaning of the Liber Floridus: A Study of the Original Manuscript (Ephraim Nissan) MARC MICHAEL EPSTEIN (ED.) Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts (Ephraim Nissan) Peter Lang Vol. 2/2016 CONSTANCE CLASSEN The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch (Ephraim Nissan) Contents Volume 2 / 2016 Vol. Articles 2 FRANCESCO BENOZZO Origins of Human Language: 2016 Deductive Evidence for Speaking Australopithecus LOUIS-JACQUES DORAIS Wendat Ethnophilology: How a Canadian Indigenous Nation is Reviving its Language Philology JOHANNES STOBBE Written Aesthetic Experience. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

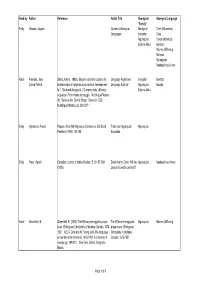

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Jacques Cartier Did Find a Passage and Gathered a Great Deal of Information About the Resources, Land and People of North America

SOCIAL 7 CHAPTER 2 Name________________________ THE FRENCH IN NORTH AMERCIA Read pages 30-35 and answer the following questions 1. Colony is a ___________________________________________ that is controlled by another country. The earliest colonists in Canada came from _______________________. (2) 2. Empires are _______________________ of ________________________ controlled by a single country, sometimes called the Home Country. (2) 3. Define Imperialism (1) _________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ Please copy the diagram of Imperialism from pg. 31. (9) 4. Why did the imperial countries of Europe want to expand their empires to North America? Please explain each reason. (8) 1._______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2._______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 3._______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 4._______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Continuation of the Negotiations with the Innu

QUEBECERS and the INNU CONTINUATION OF THE NEGOTIATIONS WITH THE INNU AGREEMENT-IN-PRINCIPLE WORKING TOGETHER TO ACHIEVE A TREATY Québec Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones Québec HOW TO PARTICIPATE IN THE NEGOTIATIONS The Government of Québec has put in place a participation mechanism that allows the populations of the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and Côte-Nord regions to make known their opinion at the negotiating table. Québec’s negotiations team includes a representative of the regions who attends all of the negotiation sessions. He is the regions’ spokesperson at the negotiating table. The representative of the regions can count on the assistance of one delegate in each of the regions in question. W HAT IS THE RO L E OF THE REP RES ENTATIV E O F THE REGIO NS AND THE DELEGATES? 1 To keep you informed of the progress made in the work of the negotiating table. 2 To consult you and obtain your comments. 3 To convey your proposals and concerns to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and to the special negotiator for the Government of Québec. WHAT IS THE AGREEM ENT-IN-P RINCIPLE? The agreement-in-principle reached by the Government of Québec, the Government of Canada and the First Nations of Betsiamites, Essipit, Mashteuiatsh and Nutashkuan will serve as a basis for negotiating a final agreement that will compromise a treaty and complementary agreements. In other words, it is a framework that will orient the pursuit of negotiations towards a treaty over the next two years. WHY NEGOTIATE? Quebecers and the Innu have lived together on the same territory for 400 years without ever deciding on the aboriginal rights of the Innu. -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

Papers from the 5Th International Co Nference on H Istoricallinguis Tics

AMSTERDAM STUDIES Ir.,-THE THEOR.Y AND HISTORY OF LINGUISTIC SCIENCE IV CURRENT ISSUES IN LINGUISTTC THEORY Volume21 Papers from the 5th International Co nference on H istoricalLinguis tics Edited by,A"ndersAhlqvist Offprint JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY THE MYSTERY OF THE VANISHED LAURENTIANS MARIANNE MITHUN When Jacques Cartier first sailed into the Bay ofGasp6 in 1534' he encountered a large fishing party. The group had come from Stada- cona, a settlement up the Saint Lawrence River where Quebec City now stands. Cartier did not remain long in the area,but when he left for France, he took two Stadaconancaptives with him. His ad- ventures in the New World are documented in an account of this first voyage. He retumed the following summer, along with his cap- tives, who now spoke some French. This time he remainedlonger, spendingmost of the winter near Stadacona,with a briefexcursion to the settlement of Hochelaga,onpresent Montreal Island"The ac- count of this secondvoyage is also rich with descriptionsof the area and its inhabitants. In 1536, Cartier again set sail for France, this time with ten captives,most from around the areaof Stadacona,al- though one girl came from a town further upriver, Achelacy- Car' tier undertook a third voyagein 1541, but little mention is made of the Laurentian inhabitants in the account ofthis voyage,norin the journal of Roberval,who attempted to found a colony there several years later. In fact,little more was everto be known of thesepeople at all. When Champlain arrived in the region in 1603, they had com- pletely vanished, Who were thesepeople, and what becameof them?r Some traces, lurk in archaeologicalsites uncovered in the vicinity of Hochelaga. -

3. Naskapi Women: Words, Narratives, and Knowledge

chapter three Naskapi Women Words, Narratives, and Knowledge Carole Lévesque, Denise Geoffroy, and Geneviève Polèse By sharing their stories and knowledge, Naskapi women have played a key role in the reconstruction of the cultural and ecological heritage of their people. The Naskapi, who live in the subarctic region of the province of Québec, today represent about nine hundred people, most of whom reside in the village of Kawawachikamach, located about fifteen kilometres from the former mining town of Schefferville, along the 55th parallel (see map 3.1). The first written reports of the Naskapi date from the late eighteenth century. It appears that, at the time of the Europeans’ arrival, the peoples to whom these reports refer did not form a single, integrated group rather they were several groups of hunters who ranged across the northern portion of the Québec Labrador peninsula (Lévesque, Rains, and de Juriew 2001). The evidence suggests that these were families or groups of hunters of Innu origin who, sometime around the mid-eighteenth century, had apparently migrated to the hinterland of the subarctic region from the North Shore of the St. Lawrence (where several Innu bands had settled). Initially few in number, the Naskapi are said to have comprised about three hundred people around 1830 (Lévesque et al. 2001). 59 doi:10.15215/aupress/9781771990417.01 Ungava Bay Québec Fort Chimo Fort McKenzie Kawawachikamach Newfoundland and Labrador Québec Map 3.1 Location of the Naskapi village of Kawawachikamach, northern Québec. Source: Laboratoire d’analyse spatiale et d’économie urbaine et régionale, Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Montréal. -

Quebec, Le 12 Octobre 2010

Quebec, October 14, 2010 By fax only to 613-957-0941 Panel Manager Project Assessment Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only to 709-729-5693 Co-Manager Lower Churchill Joint Review Panel Secretariat 33 Pippy Place PO Box 8700 St. John's NL A1B 4J6 By fax only to 613- 957-0935 Daniel Martineau Aboriginal Consultation Coordinator 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only to 709-737-1859 Todd Burlingame Nalcor Energy, Lower Churchill Project 500 Columbus Drive PO Box 12800 St. John's NL A1B 0C9 Subject: Correction regarding the Unamen Shipu Innu’s comments on the proponent, Nalcor Energy’s consultation report (Nalcor’s 2010 Consultation Assessment Report) in response to file IR# JRP.151. Maryse Pineau, Tom Graham, Daniel Martineau, Todd Burlingame: Please note there is an error in the sent version of the Unamun Shipu Innu’s comments regarding the proponent, Nalco Energy’s consultation report (Nalcor’s 2010 Consultation Assessment Report) in response to file IR# JRP.151. LITIGANTS & ADVISORS 1379 chemin Ste-Foy, Suite 210, Quebec QC G1S 2N2 Telephone: 418-527-9009 Fax: 418-527-9199 Box 199 Item 5 of our comments, titled FILE UPDATE, should read October 21, 2010 instead of October 15, 2010. Sincerely, GAUCHER LEVESQUE TABET (François Levesque) Counsel for the Unamen Shipu Innu Quebec City, October 12, 2010 By fax only 613-957-0941 Panel Manager Project Assessment Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency 22nd Floor, Place Bell Canada 160 Elgin Street Ottawa ON K1A OH3 By fax only 709-729-5693 Co-Manager Lower Churchill Joint Review Panel Secretariat 33 Pippy Place PO Box 8700 St.