Modern Language Range Mapping for the Study of Language Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

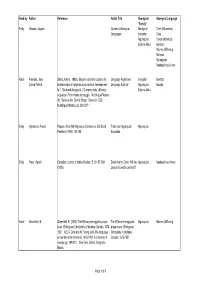

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

An Acoustic Investigation of Vowel Variation in Gitksan by Kyra Ann Fortier

An Acoustic Investigation of Vowel Variation in Gitksan By Kyra Ann Fortier (Borland-Walker) BA, University of British Columbia, 2016 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement of the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Linguistics © Kyra Ann Fortier (Borland-Walker), 2019 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii An Acoustic Investigation of Vowel Variation Across Dialects of Gitksan By Kyra Ann Fortier (Borland-Walker) BA, University of British Columbia, 2016 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sonya Bird, Supervisor Department of Linguistics, University of Victoria Dr. Alexandra D’Arcy, Departmental Member Department of Linguistics, University of Victoria Dr. Henry Davis, Affiliate Member Department of Linguistics iii Abstract The research question for this thesis is: How does vowel quality vary across Gitksan speakers, and what sociolinguistic factors may be influencing this variation? Answering this question requires both that I show what the variation is, and why it may be that way; I have approached these questions by conducting a study in two parts. First, I conducted a demographic survey and ethnographically-informed qualitative interview with nine Gitksan speakers. Second, I performed an acoustic analysis of vowel variation across these same speakers. The acoustic results lead me to conclude that the low and front vowels show the most variation between speakers. My findings allowed me to add to our understanding of individual variation across speakers and communities. Although further investigation is needed to come to a conclusion about the generalizability of these results, the overarching contribution of my work is to add phonetic detail to previous descriptions of variation between speakers within the Interior Tsimshianic dialect continuum. -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Theoretical Aspects of Gitksan Phonology by Jason Camy Brown B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2000 M.A., California St

Theoretical Aspects of Gitksan Phonology by Jason Camy Brown B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2000 M.A., California State University, Fresno, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Linguistics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2008 © Jason Camy Brown, 2008 Abstract This thesis deals with the phonology of Gitksan, a Tsimshianic language spoken in northern British Columbia, Canada. The claim of this thesis is that Gitksan exhibits several gradient phonological restrictions on consonantal cooccurrence that hold over the lexicon. There is a gradient restriction on homorganic consonants, and within homorganic pairs, there is a gradient restriction on major class and manner features. It is claimed that these restrictions are due to a generalized OCP effect in the grammar, and that this effect can be relativized to subsidiary features, such as place, manner, etc. It is argued that these types of effects are best analyzed with the system of weighted constraints employed in Harmonic Grammar (Legendre et al. 1990, Smolensky & Legendre 2006). It is also claimed that Gitksan exhibits a gradient assimilatory effect among specific consonants. This type of effect is rare, and is unexpected given the general conditions of dissimilation. One such effect is the frequency of both pulmonic pairs of consonants and ejective pairs of consonants, which occur at rates higher than expected by chance. Another is the occurrence of uvular-uvular and velar-velar pairs of consonants, which also occur at rates higher than chance. This pattern is somewhat surprising, as there is a gradient prohibition on cooccurring pairs of dorsal consonants. -

Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe

1 Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe: Traditional Resource Harvest Sites West of the Crest of the Cascades Mountains in Washington State and below the Cascades of the Columbia River Eugene Hunn Department of Anthropology Box 353100 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-3100 [email protected] for State of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife WDFW contract # 38030449 preliminary draft October 11, 2003 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Map 1 5f 1. Goals and scope of this report 6 2. Defining the relevant Indian groups 7 2.1. How Sahaptin names for Indian groups are formed 7 2.2. The Yakama Nation 8 Table 1: Yakama signatory tribes and bands 8 Table 2: Yakama headmen and chiefs 8-9 2.3. Who are the ―Klickitat‖? 10 2.4. Who are the ―Cascade Indians‖? 11 2.5. Who are the ―Cowlitz‖/Taitnapam? 11 2.6. The Plateau/Northwest Coast cultural divide: Treaty lines versus cultural 12 divides 2.6.1. The Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast versus 13 Plateau 2.7. Conclusions 14 3. Historical questions 15 3.1. A brief summary of early Euroamerican influences in the region 15 3.2. How did Sahaptin-speakers end up west of the Cascade crest? 17 Map 2 18f 3.3. James Teit‘s hypothesis 18 3.4. Melville Jacobs‘s counter argument 19 4. The Taitnapam 21 4.1. Taitnapam sources 21 4.2. Taitnapam affiliations 22 4.3. Taitnapam territory 23 4.3.1. Jim Yoke and Lewy Costima on Taitnapam territory 24 4.4. -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Assessing the Chitimacha-Totozoquean Hypothesis1

ASSESSING THE CHITIMACHA-TOTOZOQUEAN HYPOTHESIS1 DANIEL W. HIEBER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA 1. Introduction2 Scholars have attempted to genetically classify the Chitimacha language of Louisiana ever since the first vocabulary of the language was collected by Martin Duralde in 1802. Since then, there have been numerous attempts to relate Chitimacha to other isolates of the region (Swanton 1919; Swadesh 1946a; Gursky 1969), Muskogean as part of a broader Proto-Gulf hypothesis (Haas 1951; Haas 1952), and even languages as far afield as Yuki in California (Munro 1994). The most recent attempt at classification, however, looks in a new direction, and links Chitimacha with the recently-advanced Totozoquean language family of Mesoamerica (Brown, Wichmann & Beck 2014; Brown et al. 2011), providing 90 cognate sets and a number of 1 [Acknowledgements] 2 Abbreviations used in this paper are as follows: * reconstructed form ** hypothetical form intr. intransitive post. postposition tr. transitive AZR adjectivizer CAUS causative NZR nominalizer PLACT pluractional TRZR transitivizer VZR verbalizer morphological parallels as evidence. Now, recent internal reconstructions in Chitimacha made available in Hieber (2013), as well as a growing understanding of Chitimacha grammar (e.g. Hieber forthcoming), make it possible to assess the Chitimacha- Totozoquean hypothesis in light of more robust data. This paper shows that a more detailed understanding of Chitimacha grammar and lexicon casts doubt on the possibility of a genetic connection between Chitimacha and Mesoamerica. Systematic sound correspondences prove to be unattainable for the data provided in Brown, Wichmann & Beck (2014). However, groups of correspondences do appear in the data, suggestive of diffusion through contact rather than genetic inheritance. -

The Caddo After Europeans

Volume 2016 Article 91 2016 Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Timothy K. Perttula Heritage Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Robert Cast Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Perttula, Timothy K. and Cast, Robert (2016) "Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2016, Article 91. https://doi.org/10.21112/.ita.2016.1.91 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reaping the Whirlwind: The Caddo after Europeans Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2016/iss1/91 -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America.