Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relationship Between Shell - Midden S and Neolithic Paleoshorelines with Examples from Brazil and Japan *

Rev. do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, São Paulo, 3: 55-65,1993. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SHELL - MIDDEN S AND NEOLITHIC PALEOSHORELINES WITH EXAMPLES FROM BRAZIL AND JAPAN * Kenitiro Suguio** SUGUIO, K. Relationship between shell-middens and neolithic paleoshorelines with examples from Brazil and Japan. Rev. do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, Sâo Paulo, 3: 55-65, 1993. RESUMO: Este trabalho trata de aspectos gerais dos sambaquis da costa sudeste brasileira, particularmente da planície Cananéia-Iguape (SP), enfatizando a sua utilidade na reconstrução de paleolinhas de costa a partir do Holoceno médio. Algumas peculiaridades dos sambaquis da planície de Kanto (Japão), aproximadamente contemporâneos aos brasileiros, são também apresentadas. Em ambos os casos, para a identificação da posição de paleonível relativo do mar, as seguintes informações devem ser obtidas de cada sambaqui. (a) distância da atual borda marinha ou lagunar; (b) natureza e idade do substrato; (c) altitude do substrato acima do nível de maré alta; (d) épocas de ocupação e de abandono do sítio; (e) valores de Ô13C (PDB)dos carbonatos das conchas; (f) espécies predominantes de moluscos e (g) tamanho do sambaqui. UNITERMOS: Paleolinha de costa neolítica - Transgressão Santos - Transgressão Jomon - Holoceno, Brasil, Japão. Generalities hundreds of giant shell-middens (Fig. 2) are known. Their usefulness for sea-level height/ Artificial accumulations made up of shells of shoreline reconstruction has been not very clearly brackish water and marine organisms are very expressed in many papers, but this problem was commonly found in coastal regions around the more precisely emphasized in Brazil only in the world, as in Natal (South Africa), southern recent years (Martin & Suguio, 1976; Martin et Madagascar, eastern Australia (particularly the al., 1981/1982; 1986; Suguio, 1990 and Suguio “New England” coast of New South Wales), etal., 1992). -

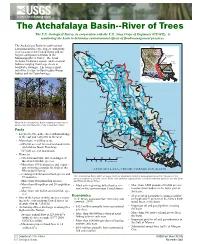

The Atchafalaya Basin

7KH$WFKDIDOD\D%DVLQ5LYHURI7UHHV The U.S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), is monitoring the basin to determine environmental effects of flood-management practices. The Atchafalaya Basin in south-central Louisiana includes the largest contiguous river swamp in the United States and the largest contiguous wetlands in the Mississippi River Valley. The basin includes 10 distinct aquatic and terrestrial habitats ranging from large rivers to backwater swamps. The basin is most noted for its cypress-tupelo gum swamp habitat and its Cajun heritage. Water in the Atchafalaya Basin originates from one or more of the distributaries of the Atchafalaya River. Facts • Located between the cities of Baton Rouge to the east and Lafayette to the west. • More than 1.4 million acres: --885,000 acres of forested wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway. --517,000 acres of marshland. • Home to: --9 Federal and State listed endangered/ threatened wildlife species. --More than 170 bird species and impor- tant wintering grounds for birds of the Mississippi Flyway. --6 endangered/threatened bird species and The Atchafalaya Basin offers an opportunity to implement adaptive management practices because of the 29 rookeries. general support of private, local, State, and national organizations and governmental agencies for the State --More than 40 mammalian species. and Federal Master Plans. --More than 40 reptilian and 20 amphibian • Most active-growing delta (land accre- • More than 1,000 pounds of finfish per acre species. tion) in the conterminous United States. in some water bodies in the lower part of --More than 100 finfish and shellfish spe- the basin. -

University of Michigan Radiocarbon Dates Xii H

[Ru)Ioc!RBo1, Vol.. 10, 1968, P. 61-114] UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN RADIOCARBON DATES XII H. R. CRANE and JAMES B. GRIFFIN The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan The following is a list of dates obtained since the compilation of List XI in December 1965. The method is essentially the same as de- scribed in that list. Two C02-CS2 Geiger counter systems were used. Equipment and counting techniques have been described elsewhere (Crane, 1961). Dates and estimates of error in this list follow the practice recommended by the International Radiocarbon Dating Conferences of 1962 and 1965, in that (a) dates are computed on the basis of the Libby half-life, 5570 yr, (b) A.D. 1950 is used as the zero of the age scale, and (c) the errors quoted are the standard deviations obtained from the numbers of counts only. In previous Michigan date lists up to and in- cluding VII, we have quoted errors at least twice as great as the statisti- cal errors of counting, to take account of other errors in the over-all process. If the reader wishes to obtain a standard deviation figure which will allow ample room for the many sources of error in the dating process, we suggest doubling the figures that are given in this list. We wish to acknowledge the help of Patricia Dahlstrom in pre- paring chemical samples and David M. Griffin and Linda B. Halsey in preparing the descriptions. I. GEOLOGIC SAMPLES 9240 ± 1000 M-1291. Hosterman's Pit, Pennsylvania 7290 B.C. Charcoal from Hosterman's Pit (40° 53' 34" N Lat, 77° 26' 22" W Long), Centre Co., Pennsylvania. -

Teaching the First American Civilization Recognizing the Moundbui

The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies Volume 77 Article 2 Number 2 Volume 77 No. 2 (2016) June 2016 Teaching The irsF t American Civilization Recognizing The oundM builders as a Great Native-American Civilization Jack Zevin Queens College/CUNY Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Geography Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Pre- Elementary, Early Childhood, Kindergarten Teacher Education Commons Recommended Citation Zevin, Jack (2016) "Teaching The irF st American Civilization Recognizing The oundM builders as a Great Native-American Civilization," The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies: Vol. 77 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol77/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ouncC ilor: A Journal of the Social Studies by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zevin: Teaching The First American Civilization Recognizing The Moundbui Teaching The First American Civilization Recognizing The Moundbuilders as a Great Native-American Civilization Jack Zevin Queens College/CUNY The Moundbuilders are a culture of mystery, little recognized by most Americans, yet they created farms, villages, towns, and cities covering as much as a third of the United States. Social studies teachers have yet to mine the resources left us over thousands of years by the native artisans and builders who preceded the nations European explorers came into contact with after 1492. -

Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed As Part of Sherburne Complex

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed as part of Sherburne Complex Tom Carlisle This basin contains over one-half million acres of hardwood swamps, lakes and bayous, and is larger than the vast Okefenokee Swamp of Georgia and Florida. It is an immense This blue goose, natural floodplain of the Atchafalaya designed by J.N. River, which flows for 140 miles south “Ding” Darling, from its parting from the Mississippi has become the River to the Gulf of Mexico. symbol of the National Wildlife The fish and wildlife resources Refuge System. of the Atchafalaya River Basin are exceptional. The basin’s dense bottomland hardwoods, cypress- tupelo swamps, overflow lakes, and meandering bayous provide a tremendous diversity of habitat for many species of fish and wildlife. Ecologists rank the basin as one of the most productive wildlife areas in North America. The basin also supports an extremely productive sport and commercial fishery, and provides unique recreational opportunities to hundreds of thousands of Americans each year. Wildlife Every year, thousands of migratory waterfowl winter in the overflow swamps and lakes of the basin, located at the southern end of the great Mississippi Flyway. The lakes of the lower basin support one of the largest wintering concentrations of canvasbacks in Louisiana. The basin’s wooded wetlands also provide vital nesting habitat for wood ducks, and support the nation’s largest concentration of American America’s Great River Swamp woodcock. More than 300 species of Deep in the heart of Cajun Country, resident and migratory birds use the basin, including a large assortment at the southern end of the Lower of diving and wading birds such as egrets, herons, ibises, and anhingas. -

Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site Benjamin Garrett Davis University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Benjamin Garrett, "Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1570. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1570 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOUSEHOLDS AND CHANGING USE OF SPACE AT THE TRANSITIONAL EARLY MISSISSIPPIAN AUSTIN SITE A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Mississippi by BENJAMIN GARRETT DAVIS May 2019 ABSTRACT The Austin Site (22TU549) is a village site located in Tunica County, Mississippi dating to approximately A.D. 1150-1350, along the transition from the Terminal Late Woodland to the Mississippian period. While Elizabeth Hunt’s (2017) masters thesis concluded that the ceramics at Austin emphasized a Late Woodland persistence, the architecture and use of space at the site had yet to be analyzed. This study examines this architecture and use of space over time at Austin to determine if they display evidence of increasing institutionalized inequality. This included creating a map of Austin based on John Connaway’s original excavation notes, and then analyzing this map within the temporal context of the upper Yazoo Basin. -

The Rock Art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II)

5 The rock art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II) Sally K. May, Paul S.C. Taçon, Duncan Wright, Melissa Marshall, Joakim Goldhahn and Inés Domingo Sanz Introduction The western Arnhem Land site of Madjedbebe – a site hitherto erroneously named Malakunanja II in scientific and popular literature but identified as Madjedbebe by senior Mirarr Traditional Owners – is widely recognised as one of Australia’s oldest dated human occupation sites (Roberts et al. 1990a:153, 1998; Allen and O’Connell 2014; Clarkson et al. 2017). Yet little is known of its extensive body of rock art. The comparative lack of interest in rock art by many archaeologists in Australia during the 1960s into the early 1990s meant that rock art was often overlooked or used simply to illustrate the ‘real’ archaeology of, for example, stone artefact studies. As Hays-Gilpen (2004:1) suggests, rock art was viewed as ‘intractable to scientific research, especially under the science-focused “new archaeology” and “processual archaeology” paradigms of the 1960s through the early 1980s’. Today, things have changed somewhat, and it is no longer essential to justify why rock art has relevance to wider archaeological studies. That said, archaeologists continued to struggle to connect the archaeological record above and below ground at sites such as Madjedbebe. For instance, at this site, Roberts et al. (1990a:153) recovered more than 1500 artefacts from the lowest occupation levels, including ‘silcrete flakes, pieces of dolerite and ground haematite, red and yellow ochres, a grindstone and a large number of amorphous artefacts made of quartzite and white quartz’. The presence of ground haematite and ochres in the lowest deposits certainly confirms the use of pigment by the early, Pleistocene inhabitants of this site. -

Recent Advances in the Prehistoric Archaeology of Formosa* by Kwang-Chih Chang and Minze Stuiver

RECENT ADVANCES IN THE PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGY OF FORMOSA* BY KWANG-CHIH CHANG AND MINZE STUIVER DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, AND DEPARTMENTS OF GEOLOGY AND BIOLOGY AND RADIOCARBON LABORATORY, YALE UNIVERSITY Communicated by Irving Rouse, January 26, 1966 The importance of Formosa (Taiwan) as a first steppingstone for the movement of peoples and cultures from mainland Asia into the Pacific islands has long been recognized. The past 70 years have witnessed considerable high-quality study of both the island's archaeology' and its ethnology,2 but it has become increasingly evident that to explore fully Formosa's position in the culture history of the Far East it is imperative also to enlist the disciplines of linguistics, ethnobiology, and the environmental sciences.3 It is with this aim that preliminary and exploratory in- vestigations were carried out in Formosa under the auspices of the Department of Anthropology of Yale University, in collaboration with the Departments of Biology at Yale, and of Archaeology-Anthropology and Geology at National Taiwan Uni- versity (Taipei, Taiwan), during 1964-65. As a result of these investigations, pre- historic cultures can now be formulated on the basis of excavated material, and be placed in a firm chronology, grounded on stratigraphic and carbon-14 evidence. This prehistoric chronology, moreover, can be related to environmental changes during the postglacial period, established by geological and palaeobiological data. Comparison of the new information with prehistoric culture histories in the ad- joining areas in Southeast China, the Ryukyus, and Southeast Asia throws light on problems of cultural origins and contacts in the Western Pacific region, and suggests ways in which to utilize Dyen's recent linguistic work,4 as well as current ethnologi- cal research. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

MASTER LIST MASTER LIST by Alphabet

Oklahoma Cemetery Directory MASTER LIST By Alphabet OHCE Genealogy Group Oklahoma County, Oklahoma Oklahoma Cemetery Directory Based on the original compilations of the 77 County Cemetery Indexes , an Oklahoma Centennial Project of Oklahoma Home and Community Education OHCE Oklahoma Cemetery Index es originally completed November 2005 2nd Edition of additions and corrections for publishing March 2008 by Oklahoma OHCE State organization Completion of name change to Oklahoma Cemetery Directory May 2009 by Oklahoma County OHCE Genealogy Group 1st Edition of Oklahoma Cemetery Directory 2010 2nd Edition of Oklahoma Cemetery Directory September 2018 Information may be copied from this book for personal use, but may not be copied for profit. ©2018 OHCE Genealogy Group Oklahoma County, Oklahoma Printed in the United States of America September 2018 Oklahoma Cemetery Directory – Master List - By Alphabet Cemetery Twp-Rng-Sec Latitude Longitude Comments County The latitude and longitude coordinates that are underlined are verified at Google Maps. The ones not underlined can’t be guaranteed . Coordinates written like this 352241N mean 35º22'41" North Coordinates written like this 0972241W mean 97º22'41" West A A L Stephens Memorial T2N-R19E-Sec29NE 343720N 0951925W aka Stephens Memorial Park; Pushmatah Park A. L. Stephen's Cem A. L. Stephen's Cemetery T2N-R19E-Sec29NE 343720N 0951925W aka A L Stephens Memorial Pushmatah Partk; NE of Clayton Aaron Cemetery T1N-R22W-Sec12NE 343446N 0992757W northwest of Olustee Jackson Aaron Pickens Cemetery T6S-R3E-Sec22 -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Reports IGERT 2013 Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science Micah Bennett Southern Illinois University Carbondale Kelley Fritz Southern Illinois University Carbondale Anne Hayden-Lesmeister Southern Illinois University Carbondale Justin Kozak Southern Illinois University Carbondale Aaron Nickolotsky Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports A report in fulfillment of the NSF IGERT Program requirements. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0903510. Recommended Citation Bennett, Micah; Fritz, Kelley; Hayden-Lesmeister, Anne; Kozak, Justin; and Nickolotsky, Aaron, "Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science" (2013). Reports. Paper 2. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IGERT at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MULTI-USE MANAGEMENT IN THE ATCHAFALAYA RIVER BASIN: RESEARCH AT THE CONFLUENCE OF PUBLIC POLICY AND ECOSYSTEM SCIENCE BY MICAH BENNETT, KELLEY FRITZ, ANNE HAYDEN-LESMEISTER, JUSTIN KOZAK, AND AARON NICKOLOTSKY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CARBONDALE NSF IGERT PROGRAM IN WATERSHED SCIENCE AND POLICY A report