Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

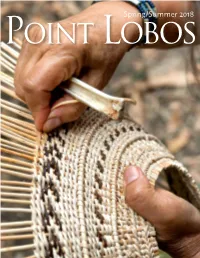

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Indian Cri'm,Inal Justice

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 1 I . ~ f .:.- IS~?3 INDIAN CRI'M,INAL JUSTICE 11\ PROG;RAM',"::llISPLAY . ,',' 'i\ ',,.' " ,~,~,} '~" .. ',:f,;< .~ i ,,'; , '" r' ,..... ....... .,r___ 74 "'" ~ ..- ..... ~~~- :":~\ i. " ". U.S. DE P ----''''---£iT _,__ .._~.,~~"ftjlX.£~~I.,;.,..,;tI ... ~:~~~", TERIOR BURE AIRS DIVISION OF _--:- .... ~~.;a-NT SERVICES J .... This Reservation criminal justice display is designed to provide information we consider pertinent, to those concerned with Indian criminal justice systems. It is not as complete as we would like it to be since reservation criminal justice is extremely complex and ever changing, to provide all the information necessary to explain the reservation criminal justice system would require a document far more exten::'.J.:ve than this. This publication will undoubtedly change many times in the near future as Indian communities are ever changing and dynamic in their efforts to implement the concept of self-determination and to upgrade their community criminal justice systems. We would like to thank all those persons who contributed to this publication and my special appreciation to Mr. James Cooper, Acting Director of the U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center, Mr •. James Fail and his staff for their excellent work in compiling this information. Chief, Division of Law Enforcement Services ______ ~ __ ---------=.~'~r--~----~w~___ ------------------------------------~'=~--------------~--------~. ~~------ I' - .. Bureau of Indian Affairs Division of Law Enforcement Services U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center Research and Statistical Unit S.UMM.ARY. ~L JUSTICE PROGRAM DISPLAY - JULY 1974 It appears from the attached document that the United States and/or Indian tribes have primary criminal and/or civil jurisdiction on 121 Indian reservations assigned administratively to 60 Agencies in 11 Areas, or the equivalent. -

Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century. Richard Xavier Sanchez Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1975 Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century. Richard Xavier Sanchez Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sanchez, Richard Xavier, "Spanish Chamber Music of the Eighteenth Century." (1975). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2893. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2893 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and dius cause a blurred image. -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

Null-Subjects, Expletives, and Locatives in Romance”

Arbeitspapier Nr. 123 Proceedings of the Workshop “Null-subjects, expletives, and locatives in Romance” Georg A. Kaiser & Eva-Maria Remberger (eds.) Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Konstanz Arbeitspapier Nr. 123 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP “NULL-SUBJECTS, EXPLETIVES, AND LOCATIVES IN ROMANCE” Georg A. Kaiser & Eva-Maria Remberger (eds.) Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft Universität Konstanz Fach 185 D-78457 Konstanz Germany Konstanz März 2009 Schutzgebühr € 3,50 Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Konstanz Sekretariat des Fachbereichs Sprachwissenschaft, Frau Tania Simeoni, Fach 185, D–78457 Konstanz, Tel. 07531/88-2465 Michael Zimmermann Katérina Palasis- Marijo Marc-Olivier Hinzelin Sascha Gaglia Georg A. Kaiser Jourdan Ezeizabarrena Jürgen M. Meisel Francesco M. Ciconte Esther Rinke Eva-Maria Franziska Michèle Oliviéri Julie Barbara Alexandra Gabriela Remberger M. Hack Auger Vance Cornilescu Alboiu Table of contents Preface Marc-Olivier Hinzelin (University of Oxford): Neuter pronouns in Ibero-Romance: Discourse reference, expletives and beyond .................... 1 Michèle Oliviéri (Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis): Syntactic parameters and reconstruction .................................................................................. 27 Katérina Palasis-Jourdan (Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis): On the variable morpho-syntactic status of the French subject clitics. Evidence from acquisition ........................................................................................................ 47 -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Teaching Written Language and Literature in Early Childhood Education

2020/2021 Teaching Written Language and Literature in Early Childhood Education Code: 103680 ECTS Credits: 7 Degree Type Year Semester 2500797 Early Childhood Education OB 3 1 The proposed teaching and assessment methodology that appear in the guide may be subject to changes as a result of the restrictions to face-to-face class attendance imposed by the health authorities. Contact Use of Languages Name: Maria Neus Real Mercadal Principal working language: catalan (cat) Email: [email protected] Some groups entirely in English: No Some groups entirely in Catalan: Yes Some groups entirely in Spanish: No Teachers Lara Reyes Lopez Martina Fittipaldi Mariona Pascual Peñas Prerequisites Students are advised to have taken and passed the course entitled Teaching Oral Language in Early Childhood Education, offered during the second year of this study programme, before enrolling in this course. Objectives and Contextualisation The course focuses mainly on the following areas: a) the features of written language discourse and the nature of reading and writing tasks; b) children learning processes, especially those concerned with the development of reading and writing skills; c) teaching and learning how to write and how to organise written tasks in the classroom; d) the different purposes of literary education at early ages, especially in the context of language immersion schools; e) the characteristics of children books and literature: types and formats of printed and digital books. f) the value of children books as educational tools to promote adult-children interaction: selection criteria to meet diverse educational goals. At the end of the course, students must: 1 - Possess (linguistic, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistic and didactic) knowledge related to the processes of teaching and learning how to write. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Cara Rachelle Monroe Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Jochim, Chair Professor Lynn Gamble Professor Michael Glassow Adjunct Professor John R. Johnson September 2014 The dissertation of Cara Rachelle Monroe is approved. ____________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble ____________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow ____________________________________________ John R. Johnson ____________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim, Committee Chair September 2014 Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). Copyright © 2014 by Cara Rahelle Monroe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing this dissertation has been an intellectual journey filled with difficulties, but ultimately rewarding in unexpected ways. I am leaving graduate school, albeit later than expected, as a more dedicated and experienced scientist who has adopted a four field anthropological research approach. This was not only the result of the mentorships and the education I received from the University of California-Santa Barbara’s Anthropology department, but also from friends -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

Drought and Equity in California

Drought and Equity in California Laura Feinstein, Rapichan Phurisamban, Amanda Ford, Christine Tyler, Ayana Crawford January 2017 Drought and Equity in California January 2017 Lead Authors Laura Feinstein, Senior Research Associate, Pacific Institute Rapichan Phurisamban, Research Associate, Pacific Institute Amanda Ford, Coalition Coordinator, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Christine Tyler, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Ayana Crawford, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Drought and Equity Advisory Committee and Contributing Authors The Drought and Equity Advisory Committee members acted as contributing authors, but all final editorial decisions were made by lead authors. Sara Aminzadeh, Executive Director, California Coastkeeper Alliance Colin Bailey, Executive Director, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Carolina Balazs, Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley Wendy Broley, Staff Engineer, California Urban Water Agencies Amanda Fencl, PhD Student, University of California, Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior Kelsey Hinton, Program Associate, Community Water Center Gita Kapahi, Director, Office of Public Participation, State Water Resources Control Board Brittani Orona, Environmental Justice and Tribal Affairs Specialist and Native American Studies Doctoral Student, University of California, Davis Brian Pompeii, Lecturer, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Tim Sloane, Executive Director, Institute for Fisheries Resources ISBN-978-1-893790-76-6 © 2017 Pacific Institute. All rights reserved. Pacific Institute 654 13th Street, Preservation Park Oakland, California 94612 Phone: 510.251.1600 | Facsimile: 510.251.2203 www.pacinst.org Cover Photos: Clockwise from top left: NNehring, Debargh, Yykkaa, Marilyn Nieves Designer: Bryan Kring, Kring Design Studio Drought and Equity in California I ABOUT THE PACIFIC INSTITUTE The Pacific Institute envisions a world in which society, the economy, and the environment have the water they need to thrive now and in the future. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

An Overview of Ohlone Culture by Robert Cartier

An Overview of Ohlone Culture By Robert Cartier In the 16th century, (prior to the arrival of the Spaniards), over 10,000 Indians lived in the central California coastal areas between Big Sur and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. This group of Indians consisted of approximately forty different tribelets ranging in size from 100–250 members, and was scattered throughout the various ecological regions of the greater Bay Area (Kroeber, 1953). They did not consider themselves to be a part of a larger tribe, as did well- known Native American groups such as the Hopi, Navaho, or Cheyenne, but instead functioned independently of one another. Each group had a separate, distinctive name and its own leader, territory, and customs. Some tribelets were affiliated with neighbors, but only through common boundaries, inter-tribal marriage, trade, and general linguistic affinities. (Margolin, 1978). When the Spaniards and other explorers arrived, they were amazed at the variety and diversity of the tribes and languages that covered such a small area. In an attempt to classify these Indians into a large, encompassing group, they referred to the Bay Area Indians as "Costenos," meaning "coastal people." The name eventually changed to "Coastanoan" (Margolin, 1978). The Native American Indians of this area were referred to by this name for hundreds of years until descendants chose to call themselves Ohlones (origination uncertain). Utilizing hunting and gathering technology, the Ohlone relied on the relatively substantial supply of natural plant and animal life in the local environment. With the exception of the dog, we know of no plants or animals domesticated by the Ohlone.