Chapter 10. Today's Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

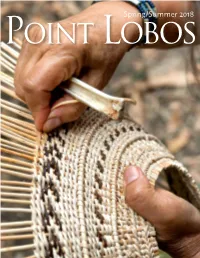

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

PROSODICALLY DRIVEN METATHESIS in MUTSUN By

Prosodically Driven Metathesis in Mutsun Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Butler, Lynnika Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 03:27:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/311476 PROSODICALLY DRIVEN METATHESIS IN MUTSUN by Lynnika Butler __________________________ Copyright © Lynnika G. Butler 2013 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2013 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Lynnika Butler, titled Prosodically Driven Metathesis in Mutsun and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (October 16, 2013) Natasha Warner -- Chair _______________________________________________ Date: (October 16, 2013) Michael Hammond _______________________________________________ Date: (October 16, 2013) Adam Ussishkin Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of -

The Mutsun Dialect of Costanoan 'Based on the Vocabulary of De La Cuesta

UNIVERSITY OF CALI FORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Vol. 11, No. 7, pp. 399-472 March 9, 1916 THE MUTSUN DIALECT OF COSTANOAN 'BASED ON THE VOCABULARY OF DE LA CUESTA BY J. ALDEN MASON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY UNIV I OF OALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS DEPAlTMENT OP ANTHROPOLOGY The following publications dealing with archaeological and -etnological subjects issued der the diron of the Department of Anthropology are sent in exchange for the publi- cations of anthropological departments and mums, and for journals devoted to general anthropology or to archaeology and ethnology. They are for sale at the prices stated, which Include postge or express charges. Exchanges should be directed to The-Exchange Depart- ment, University Library, Berkeley, California, U. S. A. All orders and remittances should be addresed to the University Press. European agent for the series in American Archaeology and Ethnology, Classical Phil- ology, Educatoin, Modem Philology, Philosophy, and Semitic Philology, Otto Harrassowits, Lipzig. For the series in Botany, Geology, Pathology, Physiology, Zoology and Also Amer- ican Archaeology and Ethnology, R. Friedlaender &. Sohn, Berlin. AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY.-A. L. Kroeber, Editor. Prices, Volume 1, $4.25; Volumes 2 to 10, inclusive, $3.50 each; Volume 11 and following, $5.00 each. Cited as Univ. Calif. Publ. Am. Arch. Ethn. Price Vol. 1. 1. Life and Culture of the Hupa, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 1-88; plates1-30. September, 1903.................................................... $1.26 2. Hupa Texts, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 89-368. March, 1904... 3.00 Index, pp. 369-378. Vol. 2. 1. The Exploration of the Potter Creek Cave, by William J. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

Some Wappo Names for People and Languages

UC Merced The Journal of California Anthropology Title Some Wappo Names for People and Languages Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0q80d4f3 Journal The Journal of California Anthropology, 3(1) Author Sawyer, J. O. Publication Date 1976-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Some Wappo Names for People and I^anguages J. O. SAWYER HE Wappo, a group of Indians located particularly shortly after a death. This T about one hundred miles north of San avoidance may have been less binding on Francisco, had a fairly usual set of traditions unrelated persons who sometimes would not for naming people. It is now too late to recover know that a death had occurred, and it was much information about their names—they probably also less binding after some time had have been mostly forgotten as have the people passed following a death.' Another taboo who were named. One aspect, however—their restricted the use of names of relatives by names for some of their neighbors—seems marriage. This taboo was carried over into interesting enough to merit separate comment English usage. Laura Somersal, perhaps the and justifies a brief review of some parts of last Wappo speaker, was usually called their naming traditions. "Laura" by her adopted son, but "aunty" by his The Wappo identified people by personal wife. The use of kinship terms for relatives by name, by kinship term, by where they came marriage as well as others was certainly part of from, or by the language or dialect they spoke. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Government Documents and Publications First Nations Era 3-10-2017 2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810" (2017). Government Documents and Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the First Nations Era at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government Documents and Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken and John R. Johnson March 2005 FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP, INC. 2727 Del Rio Place, Suite A, Davis, California, 95616 http://www.farwestern.com 530-756-3941 Prepared for Caltrans Contract No. 06A0148 & 06A0391 For individuals with sensory disabilities this document is available in alternate formats. Please call or write to: Gale Chew-Yep 2015 E. Shields, Suite 100 Fresno, CA 93726 (559) 243-3464 Voice CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. and John R. Johnson Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Submitted by: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. 2727 Del Rio Place, Davis, California, 95616 Submitted to: Valerie Levulett Environmental Branch California Department of Transportation, District 5 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 Contract No. -

On the Ethnolinguistic Identity of the Napa Tribe: the Implications of Chief Constancio Occaye's Narratives As Recorded by Lorenzo G

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title On the Ethnolinguistic Identity of the Napa Tribe: The Implications of Chief Constancio Occaye's Narratives as Recorded by Lorenzo G. Yates Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3k52g07t Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 26(2) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Johnson, John R Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 26, No. 2 (2006) | pp. 193-204 REPORTS On the Ethnolinguistic of foUdore, preserved by Yates, represent some of the only knovra tradhions of the Napa tribe, and are thus highly Identity of the Napa Tribe: sigiuficant for anthropologists mterested m comparative The Implications of oral hterature in Native California. Furthermore, the Chief Constancio Occaye^s native words m these myths suggest that a reappraisal of Narratives as Recorded the ethnohnguistic identhy of the Napa people may be by Lorenzo G. Yates in order. BACKGROUND JOHN R. JOHNSON Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Lorenzo Gordin Yates (1837-1909) was an English 2559 Puesta del Sol, Santa Barbara, CA 93105 immigrant who came to the United States as a teenager. He became a dentist by profession, but bad a lifelong About 1876, Lorenzo G. Yates interviewed Constancio passion for natural history. Yates moved his famUy from Occaye, described as the last "Chief of the Napas," and Wisconsm to California in 1864 and settled m CentreviUe recorded several items of folklore from his tribe. Yates in Alameda County, which later became a district of included Constancio's recollections about the use of Fremont.