The Carmel Pine Cone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

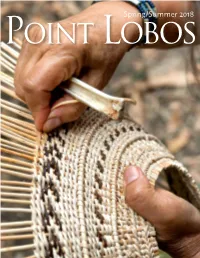

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Tributary Tribune

TRIBUTARY TRIBUNE IN THIS ISSUE Teaching Outdoor Education... PAGE 1 Indoors? Fire in the Scott Creek Watershed PAGE 3 Collaborative Restoration on Santa PAGE 3 Rosa Creek The Wild & Scenic Big Sur River PAGE 4 Conservation of Esslen Tribal Land PAGE 6 Along the Little Sur River The Importance of Estuaries for PAGE 6 Steelhead Survival Mediating Mudflows & Migration PAGE 7 Removing an Invasive Species in a PAGE 9 San Luis Obispo County Watershed Big Indications from Small PAGE 10 Invertebrates Alumni Spotlight PAGE 11 Ryan Blaich (left) and Natt McDonough (right) staking erosion control mats along Santa Rosa Creek in San Luis Obispo County, Photo credit: Hayley Barnes TEACHING OUTDOOR EDUCATION...INDOORS? What does it mean to be an environmental educator in a pre-pandemic world. Overnight, months of field trips global pandemic? Is outdoor education indoors really such were canceled, and programs were called off in an a loss? Setting aside the initial irony of teaching outdoor instant. Moving online, we began a series focused on education inside on a computer, I have been amazed by its scientific journaling with Title I students in Los Angeles. potential. As a WSP Corpsmember serving at the Resource At the beginning of each lesson I ask the question, “What Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains do you think of when you hear the word, ‘nature’?” (RCDSMM), I hit the ground running with fieldwork and Answers revolve around terms such as wildlife, leading Zoom classes. For many involved in environmental mountains, forests, and waterfalls. education, COVID-19 left little semblance to the ABOUT THE WATERSHED STEWARDS PROGRAM Since 1994, the Watershed Stewards Program (WSP) has been engaged in comprehen- sive, community-based, watershed restoration and education throughout coastal California. -

Coastal Management Accomplishments in the Big Sur Coast Area

CCC Hearing Item: Th 13.3 February 9, 2012 _______________________________________________________________ California Coastal Commission’s 40th Anniversary Report Coastal Management in Big Sur History and Accomplishments Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR SOUTHERN BIG SUR Gorda “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, southbound, north of Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Cape San Martin, Big Sur Coast. CCRP#1649 9/2/2002 “A Highway Runs Through It” Heading south on Highway One. “A Highway Runs Through It” Southbound Highway One, near Partington Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, south of Mill Creek. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Historic Big Creek Bridge, at entrance to U.C. Big Creek Reserve. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, looking south to the coastal terrace at Pacific Valley. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Monterey County line, looking south into San Luis Obispo County, with Ragged Point and Piedras Blancas in far distance (on the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 NORTHERN BIG SUR “Grand Entrance View” (from the north) of the Big Sur Coast, looking southwards to Soberanes Point, with Point Sur in the distance (on the horizon to the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Garrapata State Park/Beach, looking north to Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Mouth of Garrapata Creek (from Highway One). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Sign for Rocky Point Restaurant, with Notley’s Landing and Rocky Creek Bridge in distance. -

Shipping & Ship Wrecks

POINT SUR STATE HISTORIC PARK Shipping & Ship Wrecks Presented by: Doug Williams date Welcome to Shipping and Ship Wrecks Class. 1 Rocky Central Coast • This rocky coast has very few places for ship to land and lots of rocks to wreck them. • Shipping was use for the transport of Commerce in early California because there were very few roads and took a long time to traverse. • With more shipping came more ship wrecks which is obviously bad for Commerce. 2 Monterey Co. Early Explorers Juan Cabrillo - Punta de los Pinos Francis Drake Thomas Cavendish and the SANTA ANA 1595 Sebastián Cermeño 1542 Cabrillo landed with two ships at San Miguel Island, where he would die from an infected broken arm. His ship return to Mexico. 1572Sir Francis Drake sailed the waters off California harassing the Spanish ships but never posed a threat to their claim. 1573Thomas Cavendish and Santa Ana 1595 Sebastian Rodriquez Cermeno anchors near Pt. Sur. His boat the Buenaventura was a redwood dugout, having wrecked a Manila Galleon at Drake’s Bay. 3 Monterey Co. Early Explorers Sebastián Vizcaíno – Punta que parece Isla (Pt. Sur) – El Pais Grande del Sur (Big Sur) Gaspar de Portolá .with Father Junípero Serra Richard Henry Dana (“Pilgrim”) Commodore John Drake Sloat, USN 1602 Vizacaino mapped California Coast and rediscovered Monterey Bay. 1769 Potola along with Junipero Serra traveled by land establishing northern Mission. 1770 Richard Dana 1848 Cmd. John Sloat sails into Monterey Bay and claims it for USA. No resistance was encountered. 4 Monterey Co. Historic Periods 1542 -1769 Discovery and Exploration From Cabrillo to Portola 1770 – 1822 Mission Era - The Spanish Years 1822 Mexican Independence from Spain Fresnel Lens developed in France 1822 – 1846 Secularization of Missions Mexican Land Grants 1834 Rancho El Sur Jaun Bastista Alvarado & John Rogers Copper 1846 – 1849 American Conquest 1849 Constitutional Convention, Monterey 1850 Statehood 5 El Sur Rancho • Red Circle shows El Sur Rancho on the Map. -

Chapter 10. Today's Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008

Chapter 10. Today’s Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008 In 1928 three main Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived, those of Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan Bautista, and Mission Carmel. They had neither land nor federal treaty-based recognition. The 1930s, 1940s and 1950s were decades when descrimination against them and all California Indians continued to prevail. Nevertheless, the Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived and have renewed themselves. The 1960s and 1970s stand as transitional decades, when Ohlone/ Costanoans began to influence public policy in local areas. By the 1980s Ohlone/Costanoans were founding political groups and moving forward to preserve and renew their cultural heritage. By 1995 Albert Galvan, Mission San Jose descendent, could enunciate a strong positive vision of the future: I see my people, like the Phoenix, rising from the ashes—to take our rightful place in today’s society—back from extinction (Albert Galvan, personal communication to Bev Ortiz, 1995). Galvan’s statement stands in contrast to the 1850 vision of Pedro Alcantara, San Francisco native and ex-Mission Dolores descendant who was quoted as saying, “I am all that is left of my people. I am alone” (cited in Chapter 8). In this chapter we weave together personal themes, cultural themes, and political themes from the points of view of Ohlone/Costanoans and from the public record to elucidate the movement from survival to renewal that marks recent Ohlone/Costanoan history. RESPONSE TO DISCRIMINATION, 1900S-1950S Ohlone/Costanoans responded to the discrimination that existed during the first half of the twentieth century in several ways—(a) by ignoring it, (b) by keeping a low profile, (c) by passing as members of other ethnic groups, and/or (d) by creating familial and community support networks. -

Bigbig Sursur

CalCal PolyPoly -- PomonaPomona GeologyGeology ClubClub SpringSpring 20032003 FFieldield TTriprip BigBig SurSur David R. Jessey Randal E. Burns Leianna L. Michalka Danielle M. Wall ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors of this field guide would like to express their appreciation and sincere thanks to the Peninsula Geologic Society, the California Geological Survey and Caltrans. Without their excellent publications this guide would not have been possible. We apologize for any errors made through exclusion or addition of trip field stops. For more detailed descriptions please see the following: Zatkin, Robert (ed.), 2000, Salinia/Nacimiento Amalgamated Terrane Big Sur Coast, Central California, Peninsula Geological Society Spring Field Trip 2000 Guidebook, 214 p. Wills, C.J., Manson, M.W., Brown, K.D., Davenport, C.W. and Domrose, C.J., 2001, LANDSLIDES IN THE HIGHWAY 1 CORRIDOR: GEOLOGY AND SLOPE STABILITY ALONG THE BIG SUR COAST, California Department of Conservation Division of Mines & Geology, 43 p. 0 122 0 00' 122 0 45' 121 30 Qal Peninsula Geological Society Qal G a b i Qt la Field Trip to Salina/Nacimento 1 n R S a A n L Big Sur Coast, Central California I g N qd A e S R Qt IV E Salinas R S a lin a s Qs V Qal 101 a Qs Monterey Qc lle Qt Qp y pgm Tm Qm Seaside pgm EXPLANATION Qt Chualar Qp Qt UNCONSOLIDATED Tm pgm SEDIMENTS Qp Carmel Qal sur Qs Qal Alluvium qd CARMEL RIVER Tm Qal Point sur Qs Dune Sand Tm Lobos pgm 0 S 0 36 30 ie ' r 36 30' pgm ra Qt Quaternary non-marine d CARMEL e S terrace deposits VALLEY a Qal lin a Qt Pleistocene non-marine Tm pgm s Qc 1 Tm Tula qd rcit Qp Plio-Pleistocene non-marine qd os F ault Qm Pleistocene marine Terrace sur sur deposits qd Tm COVER ROCKS pgm qd Tm Monterey Formation, mostly qm pgm qm pgm marine biogenic and sur pgm clastic sediments middle to qdp sur qd late Miocene in age. -

Monterey County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Monterey County Salinas River The Salinas River consists of more than 75 stream miles and drains a watershed of about 4,780 square miles. The river flows northwest from headwaters on the north side of Garcia Mountain to its mouth near the town of Marina. A stone and concrete dam is located about 8.5 miles downstream from the Salinas Dam. It is approximately 14 feet high and is considered a total passage barrier (Hill pers. comm.). The dam forming Santa Margarita Lake is located at stream mile 154 and was constructed in 1941. The Salinas Dam is operated under an agreement requiring that a “live stream” be maintained in the Salinas River from the dam continuously to the confluence of the Salinas and Nacimiento rivers. When a “live stream” cannot be maintained, operators are to release the amount of the reservoir inflow. At times, there is insufficient inflow to ensure a “live stream” to the Nacimiento River (Biskner and Gallagher 1995). In addition, two of the three largest tributaries of the Salinas River have large water storage projects. Releases are made from both the San Antonio and Nacimiento reservoirs that contribute to flows in the Salinas River. Operations are described in an appendix to a 2001 EIR: “ During periods when…natural flow in the Salinas River reaches the north end of the valley, releases are cut back to minimum levels to maximize storage. Minimum releases of 25 cfs are required by agreement with CDFG and flows generally range from 25-25[sic] cfs during the minimum release phase of operations. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Government Documents and Publications First Nations Era 3-10-2017 2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810" (2017). Government Documents and Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the First Nations Era at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government Documents and Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken and John R. Johnson March 2005 FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP, INC. 2727 Del Rio Place, Suite A, Davis, California, 95616 http://www.farwestern.com 530-756-3941 Prepared for Caltrans Contract No. 06A0148 & 06A0391 For individuals with sensory disabilities this document is available in alternate formats. Please call or write to: Gale Chew-Yep 2015 E. Shields, Suite 100 Fresno, CA 93726 (559) 243-3464 Voice CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. and John R. Johnson Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Submitted by: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. 2727 Del Rio Place, Davis, California, 95616 Submitted to: Valerie Levulett Environmental Branch California Department of Transportation, District 5 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 Contract No. -

Julia Pfeiffer Burns

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Julia Pfeiffer to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological Visitors from around the Burns diversity, protecting its most valued natural and cultural resources, and creating opportunities world revere the natural for high-quality outdoor recreation. State Park beauty of the park’s rugged coastline, panoramic views, California State Parks supports equal access. crashing surf and Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the Big Sur sparkling waters. Station at (831) 649-2836. This publication is available in alternate formats by contacting: CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369. (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Discover the many states of California.™ SaveTheRedwoods.org/csp Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park 11 miles south of Big Sur on Highway 1 Big Sur, CA 93920 (831) 649-2836 www.parks.ca.gov/jpb Julia Pfeiffer Burns photo courtesy of Big Sur Historical Society © 2011 California State Parks J ulia Pfeiffer Burns State Park including the McWay and Partington dropping nearly vertically to shore offers a dramatic meeting families. Homesteaders were provide habitat for many sensitive aquatic of land and sea—attracting largely self-suffcient—making and terrestrial species. visitors, writers, artists and a living as loggers, tanoak Three perennial creeks fow through the photographers from around harvesters or ranchers by using park; Anderson, Partington and McWay the world.