California Indian Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

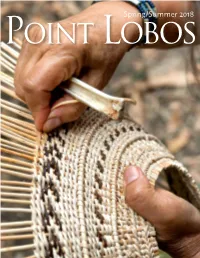

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Indian Cri'm,Inal Justice

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 1 I . ~ f .:.- IS~?3 INDIAN CRI'M,INAL JUSTICE 11\ PROG;RAM',"::llISPLAY . ,',' 'i\ ',,.' " ,~,~,} '~" .. ',:f,;< .~ i ,,'; , '" r' ,..... ....... .,r___ 74 "'" ~ ..- ..... ~~~- :":~\ i. " ". U.S. DE P ----''''---£iT _,__ .._~.,~~"ftjlX.£~~I.,;.,..,;tI ... ~:~~~", TERIOR BURE AIRS DIVISION OF _--:- .... ~~.;a-NT SERVICES J .... This Reservation criminal justice display is designed to provide information we consider pertinent, to those concerned with Indian criminal justice systems. It is not as complete as we would like it to be since reservation criminal justice is extremely complex and ever changing, to provide all the information necessary to explain the reservation criminal justice system would require a document far more exten::'.J.:ve than this. This publication will undoubtedly change many times in the near future as Indian communities are ever changing and dynamic in their efforts to implement the concept of self-determination and to upgrade their community criminal justice systems. We would like to thank all those persons who contributed to this publication and my special appreciation to Mr. James Cooper, Acting Director of the U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center, Mr •. James Fail and his staff for their excellent work in compiling this information. Chief, Division of Law Enforcement Services ______ ~ __ ---------=.~'~r--~----~w~___ ------------------------------------~'=~--------------~--------~. ~~------ I' - .. Bureau of Indian Affairs Division of Law Enforcement Services U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center Research and Statistical Unit S.UMM.ARY. ~L JUSTICE PROGRAM DISPLAY - JULY 1974 It appears from the attached document that the United States and/or Indian tribes have primary criminal and/or civil jurisdiction on 121 Indian reservations assigned administratively to 60 Agencies in 11 Areas, or the equivalent. -

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 By Kumiko Noguchi B.A. (University of the Sacred Heart) 2000 M.A. (Rikkyo University) 2003 Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Native American Studies in the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of California Davis Approved Steven J. Crum Edward Valandra Jack D. Forbes Committee in Charge 2009 i UMI Number: 3385709 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3385709 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Kumiko Noguchi September, 2009 Native American Studies From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to show the path of tribal development on the Tule River Reservation from 1776 to 1936. It ends with the year of 1936 when the Tule River Reservation reorganized its tribal government pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. -

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

History of Nuwuvi People

History of Nuwuvi People The Nuwuvi, or Southern Paiute peoples (the people), are also known as Nuwu. The Southern Paiute language originates from the uto-aztecan family of languages. Many different dialects are spoken, but there are many similarities between each language. UNLV, and the wider Las Vegas area, stands on Southern Paiute land. Historically, Southern Paiutes were hunter-gatherers and lived in small family units. Prior to colonial influence, their territory spanned across what is today Southeastern California, Southern Nevada, Northern Arizona, and Southern Utah. Within this territory, many of the Paiutes would roam the land moving from place to place. Often there was never really a significant homebase. The Las Vegas Paiute Tribe (LVPT) mentions that, “Outsiders who came to the Paiutes' territory often described the land as harsh, arid and barren; however, the Paiutes developed a culture suited to the diverse land and its resources.” Throughout the history of the Southern Paiute people, there was often peace and calm times. Other than occasional conflicts with nearby tribes, the Southern Paiutes now had to endure conflict from White settlers in the 1800s. Their way of life was now changed with the onset of construction for the Transcontinental railroad and its completion. Among other changes to the land, the LVPT also said, “In 1826, trappers and traders began crossing Paiute land, and these crossings became known in 1829 as the Old Spanish Trail (a trade route from New Mexico to California). In 1848, the United States government assumed control over the area.” The local tribe within the area is the Las Vegas Paiute Tribe (LVPT), their ancestors were known as the Tudinu (Desert People). -

Kawaiisu Basketry

Kawaiisu Basketry MAURICE L. ZIGMOND HERE are a number of fine basket Adam Steiner (died 1916), assembled at least 1 makers in Kern County, Califomia," 500 baskets from the West, and primarily from wrote George Wharton James (1903:247), "No Cahfornia, but labelled all those from Kern attempt, as far as I know, has yet been made to County simply "Kem County." They may weU study these people to get at definite knowledge have originated among the Yokuts, Tubatula as to their tribal relationships. The baskets bal, Kitanemuk, or Kawaiisu. Possibly the they make are of the Yokut type, and I doubt most complete collection of Kawahsu ware is whether there is any real difference in their to be found in the Lowie Museum of Anthro manufacture, materials or designs." The hobby pology at the University of Califomia, Berke of basket collecting had reached its heyday ley. Here the specimens are duly labelled and during the decades around the turn of the numbered. Edwin L. McLeod (died 1908) was century. The hobbyists were scattered over the responsible for acquiring this collection. country, and there were dealers who issued McLeod was eclectic in his tastes and, unhke catalogues advertising their wares. A Basket Steiner, did not hmit his acquisitions to items Fraternity was organized by George Wharton having esthetic appeal. James (1903:247) James who, for a one dollar annual fee, sent observed: out quarterly bulletins.^ Undoubtedly the best collection of Kern While some Indian tribes were widely County baskets now in existence is that of known for their distinctive basketry, the deal Mr. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59b7c0n9 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Cohen, Bill Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Antliropology Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-34 (1987). Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California BILL COHEN, 746 Westholme Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024. OANDPAINTINGS created by native south were similar in technique to the more elab ern Californians were sacred cosmological orate versions of the Navajo, they are less maps of the universe used primarily for the well known. This is because the Spanish moral instruction of young participants in a proscribed the religion in which they were psychedelic puberty ceremony. At other used and the modified native culture that times and places, the same constructions followed it was exterminated by the 1860s. could be the focus of other community ritu Southern California sandpaintings are among als, such as burials of cult participants, the rarest examples of aboriginal material ordeals associated with coming of age rites, culture because of the extreme secrecy in or vital elements in secret magical acts of which they were made, the fragility of the vengeance. The "paintings" are more accur materials employed, and the requirement that ately described as circular drawings made on the work be destroyed at the conclusion of the ground with colored earth and seeds, at the ceremony for which it was reproduced. -

Fort Mojave Indian Tribe Tribal State Gaming Compact

FORT MOJAVE INDIAN TRIBE AND STATE OF ARIZONA GAMING COMPACT 2002 THE FORT MOJAVE INDIAN TRIBE - STATE OF ARIZONA GAMING COMPACT DECLARATION OF POLICY AND PURPOSE .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 SECTION1. TITLE .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 SECTION2. DEFINITIONS . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 SECTION 3. NATURE, SIZE AND CONDUCT OF CLASS Ill GAMING . .. .. .. .. 8 (a) Authorized Class Ill Gaming Activities . .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 (b) Appendices Governing Gaming .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 (c) Number of Gaming Device Operating Rights and Number of Gaming Facilities .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 ( d) Transfer of Gaming Device Operating Rights . .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 (e) Number of Card Game Tables .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 (f) Number of Keno Games .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 (g) Inter-Tribal Parity Provisions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 (h) Additional Gaming Due to Changes in State Law with Respect to Persons Other Than Indian Tribes. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 (i) Notice .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 0) Location of Gaming Facility . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 (k) Financial Services in Gaming Facilities .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 (I) Forms of Payment for Wagers .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 (m) Wager Limitations .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 (n) Hours of Operation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 (o) Ownership of Gaming Facilities and Gaming Activities . .. .. .. 20 (p) Prohibited Activities ........................................ 21 (q ) Operation as Part of a Network . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 (r) Prohibition -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

Drought and Equity in California

Drought and Equity in California Laura Feinstein, Rapichan Phurisamban, Amanda Ford, Christine Tyler, Ayana Crawford January 2017 Drought and Equity in California January 2017 Lead Authors Laura Feinstein, Senior Research Associate, Pacific Institute Rapichan Phurisamban, Research Associate, Pacific Institute Amanda Ford, Coalition Coordinator, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Christine Tyler, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Ayana Crawford, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Drought and Equity Advisory Committee and Contributing Authors The Drought and Equity Advisory Committee members acted as contributing authors, but all final editorial decisions were made by lead authors. Sara Aminzadeh, Executive Director, California Coastkeeper Alliance Colin Bailey, Executive Director, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Carolina Balazs, Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley Wendy Broley, Staff Engineer, California Urban Water Agencies Amanda Fencl, PhD Student, University of California, Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior Kelsey Hinton, Program Associate, Community Water Center Gita Kapahi, Director, Office of Public Participation, State Water Resources Control Board Brittani Orona, Environmental Justice and Tribal Affairs Specialist and Native American Studies Doctoral Student, University of California, Davis Brian Pompeii, Lecturer, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Tim Sloane, Executive Director, Institute for Fisheries Resources ISBN-978-1-893790-76-6 © 2017 Pacific Institute. All rights reserved. Pacific Institute 654 13th Street, Preservation Park Oakland, California 94612 Phone: 510.251.1600 | Facsimile: 510.251.2203 www.pacinst.org Cover Photos: Clockwise from top left: NNehring, Debargh, Yykkaa, Marilyn Nieves Designer: Bryan Kring, Kring Design Studio Drought and Equity in California I ABOUT THE PACIFIC INSTITUTE The Pacific Institute envisions a world in which society, the economy, and the environment have the water they need to thrive now and in the future.