From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, However, Went Unnoticed

• D -1:>K 1.2!;EQUOJA-KING$ Ci\NYON NATIONAL PARKS History of the Parks "''' Evaluation of Historic Resources Detennination of Effect, DCP Prepared by • A. Berle Clemensen DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEA.'! NATIONAL PAP.K SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPAR'J'}fENT OF THE l~TERIOR DENVER, COLOR..\DO SEPTEffilER 1975 i i• Pl.EA5!: RETUl1" TO: B&WScans TEallillCAL INFORMAl!tll CfNIEil 0 ·l'i «coo,;- OOIVER Sf:RV!Gf Cf!fT£R llAT!ONAL PARK S.:.'Ma j , • BRIEF HISTORY OF SEQUOIA Spanish and Mexican Period The first white men, the Spanish, entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1772. They, however, only observed the Sierra Nevada mountains. None entered the high terrain where the giant Sequoia exist. Only one explorer came close to the Sierra Nevadas. In 1806 Ensign Gabriel Moraga, venturing into the foothills, crossed and named the Rio de la Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings) or Kings River. Americans in the San Joaquin Valley The first band of Americans entered the Valley in 1827 when Jedediah Smith and a group of fur traders traversed it from south to north. This journey ushered in the first American frontier as fifteen years of fur trapping followed. Still, none of these men reported sighting the giant trees. It was not until 1833 that members of the Joseph R. 1lalker expedition crossed the Sierra Nevadas and received credit as the first whites to See the Sequoia trees. These trees are presumed to form part of either the present M"rced or Tuolwnregroves. Others did not learn of their find since Walker's group failed to report their discovery. -

Giant Sequoia National Monument Vegetation Specialist Report

Giant Sequoia National Monument Vegetation Specialist Report Signature: ______________________________ Date: _________________________________ 1 The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 2 Vegetation, Including Giant Sequoias Table of Contents Vegetation, Including Giant Sequoias ............................................................................................ 3 Desired Conditions ...................................................................................................................... 4 Giant Sequoias ......................................................................................................................... 5 Mixed Conifer Forest............................................................................................................... 5 Blue Oak–Interior Live Oak (Foothill -

Kawaiisu Basketry

Kawaiisu Basketry MAURICE L. ZIGMOND HERE are a number of fine basket Adam Steiner (died 1916), assembled at least 1 makers in Kern County, Califomia," 500 baskets from the West, and primarily from wrote George Wharton James (1903:247), "No Cahfornia, but labelled all those from Kern attempt, as far as I know, has yet been made to County simply "Kem County." They may weU study these people to get at definite knowledge have originated among the Yokuts, Tubatula as to their tribal relationships. The baskets bal, Kitanemuk, or Kawaiisu. Possibly the they make are of the Yokut type, and I doubt most complete collection of Kawahsu ware is whether there is any real difference in their to be found in the Lowie Museum of Anthro manufacture, materials or designs." The hobby pology at the University of Califomia, Berke of basket collecting had reached its heyday ley. Here the specimens are duly labelled and during the decades around the turn of the numbered. Edwin L. McLeod (died 1908) was century. The hobbyists were scattered over the responsible for acquiring this collection. country, and there were dealers who issued McLeod was eclectic in his tastes and, unhke catalogues advertising their wares. A Basket Steiner, did not hmit his acquisitions to items Fraternity was organized by George Wharton having esthetic appeal. James (1903:247) James who, for a one dollar annual fee, sent observed: out quarterly bulletins.^ Undoubtedly the best collection of Kern While some Indian tribes were widely County baskets now in existence is that of known for their distinctive basketry, the deal Mr. -

Giant Sequoia National Monument Management Plan 2012 Final Environmental Impact Statement Record of Decision Sequoia National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Giant Sequoia Forest Service Sequoia National Monument National Forest August 2012 Record of Decision The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Giant Sequoia National Monument Management Plan 2012 Final Environmental Impact Statement Record of Decision Sequoia National Forest Lead Agency: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region Responsible Official: Randy Moore Regional Forester Pacific Southwest Region Recommending Official: Kevin B. Elliott Forest Supervisor Sequoia National Forest California Counties Include: Fresno, Tulare, Kern This document presents the decision regarding the the basis for the Giant Sequoia National Monument selection of a management plan for the Giant Sequoia Management Plan (Monument Plan), which will be National Monument (Monument) that will amend the followed for the next 10 to 15 years. The long-term 1988 Sequoia National Forest Land and Resource environmental consequences contained in the Final Management Plan (Forest Plan) for the portion of the Environmental Impact Statement are considered in national forest that is in the Monument. -

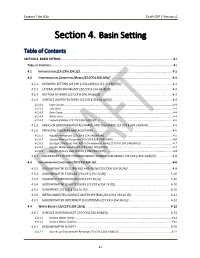

Section 4. Basin Setting

Eastern Tule GSA Draft GSP | Section 4 Section 4. Basin Setting Table of Contents SECTION 4. BASIN SETTING ............................................................................................................................... 4-I TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................................................................................... 4-I 4.1 INTRODUCTION [23 CCR § 354.12] ........................................................................................................ 4-1 4.2 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONCEPTUAL MODEL [23 CCR § 354.14(A)] ..................................................................... 4-1 4.2.1 GEOLOGIC SETTING [23 CCR § 354.14(B)(1), (C), (D)(1)(2)(3)] ............................................................. 4-2 4.2.2 LATERAL BASIN BOUNDARY [23 CCR § 354.14 (B)(2)] .......................................................................... 4-3 4.2.3 BOTTOM OF BASIN [23 CCR § 354.14 (B)(3)] ....................................................................................... 4-3 4.2.4 SURFACE WATER FEATURES [23 CCR § 354.14 (D)(5)] ......................................................................... 4-4 4.2.4.1 Lake Success ................................................................................................................................................. 4-4 4.2.4.2 Tule River ..................................................................................................................................................... 4-4 4.2.4.3 -

Mello May 2012

ABSTRACT THE STRESS SYSTEM OF CHUKCHANSI YOKUTS The stress system of Chukchansi, a variety of Yokuts, has never been studied in any detail. In this thesis, I illustrate how primary stress works followed by its acoustic correlates. I first illustrate that primary stress is attracted first and foremost to long-vowel syllables. When no long vowel is present, stress is, by default, on the penultimate syllable. Stress acoustically manifests itself most strongly with greater intensity. Intensity is shown to be a strong correlate of stress as it consistently makes inherently less-intense vowels more intense than neighboring inherently more-intense vowels. Pitch too is shown to be a consistent and reliable correlate of stress; every stressed syllable contains higher a pitch than non-stressed syllables. Vowel lengthening and vowel quality differences are shown to not be reliable acoustic correlates of stress in Chukchansi. Daniel Correia Mello May 2012 THE STRESS SYSTEM OF CHUKCHANSI YOKUTS by Daniel Correia Mello A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2012 APPROVED For the Department of Linguistics: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Daniel Correia Mello Thesis Author Sean Fulop (Chair) Linguistics Brian Agbayani Linguistics Xinchun Wang Linguistics For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. -

Payment of Taxes As a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: a Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 9 | Number 1 Article 13 1-1-1969 Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q. Mix Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Averill Q. Mix, Comment, Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism, 9 Santa Clara Lawyer 244 (1969). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol9/iss1/13 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PAYMENT OF TAXES AS A CONDITION OF TITLE BY ADVERSE POSSESSION: A NINETEENTH CENTURY ANACHRONISM In California the basic statute governing the obtaining of title to land by adverse possession is section 325 of the Code of Civil Procedure.' This statute places California with the small minority of states that unconditionally require payment of taxes as a pre- requisite to obtaining such title. The logic of this requirement has been under continual attack almost from its inception.2 Some of its defenders state, however, that it serves to give the true owner notice of an attempt to claim his land adversely.' Superficially, the law in California today appears to be well settled, but litigation in which the tax payment requirement is a prominent issue continues to arise. -

Cultural Resources and Tribal and Native American Interests

Giant Sequoia National Monument Specialist Report Cultural Resources and Tribal and Native American Interests Signature: __________________________________________ Date: _______________________________________________ The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14 th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Giant Sequoia National Monument Specialist Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Current Management Direction ................................................................................................................. 1 Types of Cultural Resources .................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives .............................................................................................................................................. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

The California Gold Rush

SECTION 4 The California Gold Rush What You Will Learn… If YOU were there... Main Ideas You are a low-paid bank clerk in New England in early 1849. Local 1. The discovery of gold newspaper headlines are shouting exciting news: “Gold Is Discovered brought settlers to California. 2. The gold rush had a lasting in California! Thousands Are on Their Way West.” You enjoy hav- impact on California’s popula- ing a steady job. However, some of your friends are planning to tion and economy. go West, and you are being infl uenced by their excitement. Your friends are even buying pickaxes and other mining equipment. The Big Idea They urge you to go West with them. The California gold rush changed the future of the West. Would you go west to seek your fortune in California? Why? Key Terms and People John Sutter, p. 327 Donner party, p. 327 BUILDING BACKGROUND At the end of the Mexican-American forty-niners, p. 327 War, the United States gained control of Mexican territories in the West, prospect, p. 328 including all of the present-day state of California. American settle- placer miners, p. 328 ments in California increased slowly at first. Then, the discovery of gold brought quick population growth and an economic boom. Discovery of Gold Brings Settlers In the 1830s and 1840s, Americans who wanted to move to Califor- nia started up the Oregon Trail. At the Snake River in present-day Idaho, the trail split. People bound for California took the southern HSS 8.8.3 Describe the role of pio- route, which became known as the California Trail. -

Pamphlet Accompanying Microcopy No. 234 LETTERS RECEIVED BY

NATIONAL ARCHIVES MICROFILM PUBLICATIONS Pamphlet Accompanying Microcopy No. 234 LETTERS RECEIVED BY THE OFFICE OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, 1824-80 THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON: 1966 LETTERS RECEIVED BY THE OFFICE OF INDIAN AFFAIRS 182^-80 On the 962 rolls of this microfilm publication is reproduced the greater part of the correspondence re- ceived by the central office of the Bureau of Indian Af- fairs during the years 182^ through l880« The corre- spondence not included consists of letters and documents organized by the Bureau into various special series, which are discussed in more detail below. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was established within the War Department on March 11, l82lj, by order of Sec- retary of War John C. Calhoun (H. Doc. lU6, 1st sess., 19th Cong., p. 6). From 1789 until 182^ the administration of Indian Affairs had been under the direct supervision of the Secretary of War with the exception of the Government-, operated system of factories for trade with the Indians* From 1806 to 1822, the year of its abolition, this sys- tem was administered by a Superintendent of Indian Trade who was responsible to the Secretary of War. Six volumes of letters relating to Indian Affairs sent by the Sec- retary of War, l800-2lj, have been reproduced as Micro- film Publication 15- Letters sent by the Superintendent of Indian Trade from 1807 to 1822, also recorded in six volumes, with a seventh volume covering the office in liquidation after 1822, are reproduced as Microfilm Publication l6. The incoming letters of the Secretary of War relating to Indian affairs from 1800 to 182*4 are divided into three series. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family.