Pamphlet Accompanying Microcopy No. 234 LETTERS RECEIVED BY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-Creation of the Tribal Identity On

From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican Contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 By Kumiko Noguchi B.A. (University of the Sacred Heart) 2000 M.A. (Rikkyo University) 2003 Dissertation Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Native American Studies in the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of California Davis Approved Steven J. Crum Edward Valandra Jack D. Forbes Committee in Charge 2009 i UMI Number: 3385709 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3385709 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Kumiko Noguchi September, 2009 Native American Studies From Yokuts to Tule River Indians: Re-creation of the Tribal Identity on the Tule River Indian Reservation in California from Euroamerican contact to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to show the path of tribal development on the Tule River Reservation from 1776 to 1936. It ends with the year of 1936 when the Tule River Reservation reorganized its tribal government pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. -

Section 4. Basin Setting

Eastern Tule GSA Draft GSP | Section 4 Section 4. Basin Setting Table of Contents SECTION 4. BASIN SETTING ............................................................................................................................... 4-I TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................................................................................... 4-I 4.1 INTRODUCTION [23 CCR § 354.12] ........................................................................................................ 4-1 4.2 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONCEPTUAL MODEL [23 CCR § 354.14(A)] ..................................................................... 4-1 4.2.1 GEOLOGIC SETTING [23 CCR § 354.14(B)(1), (C), (D)(1)(2)(3)] ............................................................. 4-2 4.2.2 LATERAL BASIN BOUNDARY [23 CCR § 354.14 (B)(2)] .......................................................................... 4-3 4.2.3 BOTTOM OF BASIN [23 CCR § 354.14 (B)(3)] ....................................................................................... 4-3 4.2.4 SURFACE WATER FEATURES [23 CCR § 354.14 (D)(5)] ......................................................................... 4-4 4.2.4.1 Lake Success ................................................................................................................................................. 4-4 4.2.4.2 Tule River ..................................................................................................................................................... 4-4 4.2.4.3 -

Hydrogeological Conceptual Model and Water Budget of the Tule Subbasin Volume 1 August 1, 2017

Hydrogeological Conceptual Model and Water Budget of the Tule Subbasin Volume 1 August 1, 2017 Tule Subbasin Lower Tule River ID GSA Pixley ID GSA Eastern Tule GSA Alpaugh GSA Delano- Earlimart Tri-County Water ID GSA Authority GSA Prepared for The Tule Subbasin MOU Group Tule Subbasin MOU Group Hydrogeological Conceptual Model and Water Budget of the Tule Subbasin 1-Aug-17 Table of Contents Volume 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Tule Subbasin Area .......................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Types and Sources of Data ............................................................................................... 7 2.0 Hydrological Setting of the Tule Subbasin .......................................................................... 9 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Historical Precipitation Trends......................................................................................... 9 2.3 Historical Land Use .......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Surface Water Features ................................................................................................. -

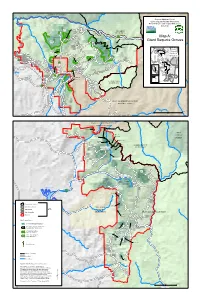

Map A: Giant Sequoia Groves

SIERRA NATIONAL FOREST K Sequoia National Forest i ng s Ri ve r Giant Sequoia National Monument Final Environmental Impact Statement July 2012 Boole Indian Tree Basin MONARCH WILDERNESS Converse Basin Map A: Monarch Chicago Giant Sequoia Groves Stump Hume Evans Complex Agnew Sierra National Forest Kings Canyon Giant Sequoia National Deer National Forest Park Sequoia Cherry Gap Meadow National Abbott Creek Monument Sequoia Bearskin National Park Inyo Grant National Visalia Landslide ! Forest Big Sequoia Porterville Sequoia National ! National Forest Stump Forest Monument Redwood Roads Mountain " JENNIE LAKES 0 50 100 200 300 400 500 Miles Bakersfield ! WILDERNESS SEQUOIA AND KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS er Ri v eah w a K rk Fo t h Nor 0 1.25 2.5 5 Miles SEQUOIA AND KINGS CANYON NATIONAL PARKS Dillonwood INYO Maggie NATIONAL Upper Mountain Tule FOREST Silver Creek Middle er iv Tule R le Burro Creek u GOLDEN TROUT T k Mountain Home WILDERNESS r o State Forest F h t r o Mountain N Home L i t tl e K e r n Rive Wishon r Alder Creek Bush Tree Camp Nelson Freeman Creek Springville Belknap Complex r e v i Black R Mountain Ponderosa Lake Success Tu l e Redhill Sequoia National Forest Peyrone Other National Forest TULE RIVER Land National Park Status INDIAN Other Ownership RESERVATION SEQUOIA NATIONAL FOREST Monument South Peyrone Giant Sequoia Groves Grove (Administrative Boundary) Johnsondale Freeman Creek Grove Administrative Boundary (Alternatives C & D) Long Meadow Cunningham Grove Influence Zone (Alternatives A & E) Starvation Grove Zone of Influence Complex (Alternatives B & F) Packsaddle Named Sequoia Powderhorn Tree K e r n R i v e r California Hot Springs Wilderness Boundary Main Road River / Stream Deer Creek SOURCE: USDAFS, Sequoia National Forest, 2012 e Riv e r h it DISCLAIMER: This product is reproduced from W geospatial information prepared by the USDA Forest Service. -

Floods of December 1966 in the Kern-Kaweah Area, Kern and Tulare Counties, California

Floods of December 1966 in the Kern-Kaweah Area, Kern and Tulare Counties, California GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1870-C Floods of December 1966 in the Kern-Kaweah Area, Kern and Tulare Counties, California By WILLARD W. DEAN fPith a section on GEOMORPHIC EFFECTS IN THE KERN RIVER BASIN By KEVIN M. SCOTT FLOODS OF 1966 IN THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1870-C UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. A. Radlinski, Acting Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-610922 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract_____________________________________________________ Cl Introduction.____________ _ ________________________________________ 1 Acknowledgments. ________________________________________________ 3 Precipitation__ ____________________________________________________ 5 General description of the floods___________________________________ 9 Kern River basin______________________________________________ 12 Tule River basin______________________________________________ 16 Kaweah River basin____________________________--_-____-_---_- 18 Miscellaneous basins___________________________________________ 22 Storage regulation _________________________________________________ 22 Flood damage.__________________________________________________ 23 Comparison to previous floods___________-_____________--___------_ -

Draft EA, Lower Tule River Irrigation District Intertie Project

Draft Environmental Assessment Lower Tule River Irrigation District Tule River Intertie Project EA-09-73 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid Pacific Region South Central California Area Office Fresno, California December 2009 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Table of Contents Section 1 Purpose and Need for Action....................................................... 1 1.1 Background........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose and Need ................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope..................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Potential Issues...................................................................................... 2 Section 2 Alternatives Including the Proposed Action............................... 3 2.1 Proposed Action.................................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Wood Central Ditch Modifications............................................. 3 2.1.2 Construction of the Intertie Canal.............................................. -

Origin of Meter-Size Granite Basins in the Southern Sierra Nevada, California

Origin of Meter-Size Granite Basins in the Southern Sierra Nevada, California Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5210 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover—Rainwater pond in granite basin at Quail Flat site. Water is 110 cm in diameter and 20 cm deep; upper white rim is 148 cm in diameter. Origin of Meter-Size Granite Basins in the Southern Sierra Nevada, California By James G. Moore, Mary A. Gorden, Joel E. Robinson, and Barry C. Moring Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5210 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey ii U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 This report and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2008/5210/ For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Produced in the Western Region, Menlo Park, California Manuscript approved for publication, October 29, 2008 Text edited by Peter Stauffer Layout and Design by Jeanne S. -

California Indian Warfare

47 CALIFORNIA INDIAN WARFARE Steven R. James Suzanne Graziani 49 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION NORTHERN CALIFORNIA TRIBES CENTRAL COAST TRIBES CENTRAL INTERIOR TRIBES SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA TRIBES COLORADO RIVER TRIBES DISCUSSION APPENDIX 1 A List of Warfare Encounters Between Tribes ILLUSTRATION Map Showing Names and Territories of California Tribes BIBLIOGRAPHY 51 INTRODUCTION With the exception of the Mohave and the Yuma Indians along the Colorado River, the tribes of California were considered to be peaceful, yet peaceful is an ambiguous word. While there was no large-scale or organized warfare outside the Colorado River area, all tribes seemed to be, at one time or another, engaged in fighting with their neighbors. There was a great deal of feuding between groups (tribelets or villages) within the individual tribes, also. The basic cause for warfare was economic competition, which included trespassing, and poaching, as well as murder. The Mohave and the Yuma, on the other hand, glorified war for itself. The ambiguity of the word "peaceful" is increased by the accounts in the ethnographies. For example, a tribe may be described as being "peaceful;" yet, warfare with certain neighbors was said to be "common." At times, there were actual contradictions in the information concerning tribal warfare and intertribal relationships. Apparently, each California tribe had contact with most of its neighbors, but for the purposes of this paper, we have divided the state into the following five areas of interaction: the Northern tribes, the Central Coast tribes, the Southern tribes, the Central Interior tribes, and tie Colorado River tribes. Within each area, we have attempted to ascertain which tribes were in agreement and which tribes were in conflict, and if the conflicts were chronic. -

Poso Creek Integrated Regional Water Management Plan

Poso Creek Integrated Regional Water Management Plan —Adopted July 2007— Poso Creek IRWMP Regional Management Group and Region The Poso Creek Regional Management Group (Regional These districts overlie the groundwater basin in the Tulare Lake Management Group) comprises seven agricultural districts Basin Hydrologic area located in the northerly portion of Kern and one resource conservation district listed below. County and southerly portion of Tulare County. The Poso Creek IRWMP Region (Region) is a fertile agricultural area with a current • Semitropic Water Storage District – Lead Agency annual gross value of agricultural commodities estimated at • Cawelo Water District $2 billion. The rich soils, climate, and irrigation water make it possible to grow predominately high-value, permanent crops. The • Delano-Earlimart Irrigation District largest value commodities – almonds, grapes, citrus, pistachios, • Kern-Tulare Water District and vegetables – are sold worldwide. • North Kern Water Storage District The Poso Creek IRWMP emphasizes resolving the Region’s short- • Rag Gulch Water District term and long-term water supply challenges through an integrated water resource planning approach. The Poso Creek IRWMP • Shafter-Wasco Irrigation District includes development of regional water management strategies • North West Kern Resource Conservation to address the Region’s needs and the framework for prioritizing District and implementing them. The focus of the Regional Management Group is to improve water supplies throughout the Region. The Regional Management Group adopted the Poso Creek Integrated Regional Water Management Plan (Poso Creek IRWMP) in July of 2007. Notes: Regional Management 1. The boundary of Area (RMA) the RMG and Region -or- Region encompasses all of the area within the districts; however, to the extent that Regional Management the NWKRCD boundary Group (RMG) includes area outside of the districts, the NWKRCD boundary lines are not included. -

Giant Sequoia National Monument, Draft Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1 1 Chapter 3 Affected Environment

United States Department of Giant Sequoia Agriculture Forest Service National Monument Giant Sequoia National Monument Draft Environmental Impact Statement August 2010 Volume 1 The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Chapter 3 - Affected Environment Giant Sequoia National Monument, Draft Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1 1 Chapter 3 Affected Environment Volume 1 Giant Sequoia National Monument, Draft Environmental Impact Statement 2 Chapter 3 Affected Environment Chapter 3 Affected Environment Chapter 3 describes the affected environment or existing condition by resource area, as each is currently managed. This is the baseline condition against which environmental effects are evaluated and from which progress toward the desired condition can be measured. Vegetation, including Giant Sequoia Groves Vegetation within the Giant Sequoia National Monument can be grouped into ecological units with similar climatic, geology, soils, and vegetation communities. These units fall within three categories: oak woodlands/grasslands, shrublands/chaparral, and forestlands. The forested category between 5,000 and 7,000 feet in elevation, spanning the Monument from north to south, is dominated by mixed conifer and its variants. -

Cultural Resources

The U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14 th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Giant Sequoia National Monument Specialist Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Current Management Direction ................................................................................................................. 1 Types of Cultural Resources .................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Monitoring ............................................................................................................................................. -

Tulare County General Plan

Draft Tulare County General Plan APPENDIX A: EXCERPTS FROM TULARE COUNTY CEDS County Infrastructure Projects 1) Goshen Redevelopment Project Area – North Goshen Industrial Area Sewer and Water Extensions - The project will extend sewer service to vacant industrial properties in the north and northeast of the community (North Goshen Industrial Area) and require installation of a new pump station. The project will also upgrade the existing water distribution system, extend the water lines 1,700 feet to the north, construct a water storage facility, and a new domestic well. Currently the sewer lines are 600 feet short of reaching the periphery of the subject area and the water distribution system is undersized and incapable of providing required fire flows. The project may be undertaken in 2004/05 in cooperation with Goshen CSD and California Water Service Co., as new industrial prospects will require extension of sewer and water services. Currently applying for funding with which to construct the project. Status: The project is in the study phase. 2) Goshen Redevelopment Project Area - Betty Drive Interchange Improvements - Caltrans has improved the travel lanes and added a sidewalk to the Betty Drive Bridge as a temporary measure to improve pedestrian and traffic safety within the vicinity of the bridge. In conjunction with this project, in 2004, Caltrans will construct a pedestrian overcrossing bridge along the Ave. 308 alignment, approximately 1,000 feet south of the Betty Drive interchange, to link students on the east side of State Road 99 with the elementary school on its west side. Caltrans replaced the existing bridge travel surface with wider travel lanes (12 feet each way) and a new handicap compliant sidewalk (7.5 feet) on the south side.