Anthropological Records 15:1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

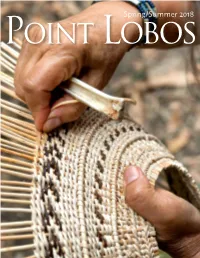

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Chapter 10. Today's Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008

Chapter 10. Today’s Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008 In 1928 three main Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived, those of Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan Bautista, and Mission Carmel. They had neither land nor federal treaty-based recognition. The 1930s, 1940s and 1950s were decades when descrimination against them and all California Indians continued to prevail. Nevertheless, the Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived and have renewed themselves. The 1960s and 1970s stand as transitional decades, when Ohlone/ Costanoans began to influence public policy in local areas. By the 1980s Ohlone/Costanoans were founding political groups and moving forward to preserve and renew their cultural heritage. By 1995 Albert Galvan, Mission San Jose descendent, could enunciate a strong positive vision of the future: I see my people, like the Phoenix, rising from the ashes—to take our rightful place in today’s society—back from extinction (Albert Galvan, personal communication to Bev Ortiz, 1995). Galvan’s statement stands in contrast to the 1850 vision of Pedro Alcantara, San Francisco native and ex-Mission Dolores descendant who was quoted as saying, “I am all that is left of my people. I am alone” (cited in Chapter 8). In this chapter we weave together personal themes, cultural themes, and political themes from the points of view of Ohlone/Costanoans and from the public record to elucidate the movement from survival to renewal that marks recent Ohlone/Costanoan history. RESPONSE TO DISCRIMINATION, 1900S-1950S Ohlone/Costanoans responded to the discrimination that existed during the first half of the twentieth century in several ways—(a) by ignoring it, (b) by keeping a low profile, (c) by passing as members of other ethnic groups, and/or (d) by creating familial and community support networks. -

Table 5-4. the North American Tribes Coded for Cannibalism by Volhard

Table 5-4. The North American tribes coded for cannibalism by Volhard and Sanday compared with all North American tribes, grouped by language and region See final page for sources and notes. Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. Family Group or Dialect Culture No. Language 1. Tribes with reports of cannibalism in Volhard, by region and language Language groups found mainly in the North and West Western Nadene Athapascan Northern Athapascan 798 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Chipewayan Northern ND7 Tschipewayan 799 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Slave Northern ND14 128 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Yellowknife Northern ND14 Subarctic Canada Northwest Salishan Coast Salish Bella Coola Bella Coola British NE6 132 Bilchula, Bilqula 795 Coast Columbia Northwest Penutian Tsimshian Tsimshian Tsimshian British NE15 Tsimschian 793 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Helltsuk Helltsuk British NE5 Heiltsuk 794 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Kwakiutl Kwakiutl British NE10 Kwakiutl* 792, 96, 97 Coast Columbia California Penutian Maidun Maidun Nisenan California NS15 Nishinam* 809, 810 California Yukian Yuklan Yuklan Wappo California NS24 Wappo 808 Language groups found mainly in the Plains Plains Sioux Dakota West Central Plains Sioux Dakota Assiniboin Assiniboin Prairie NF4 Dakota 805 Plains Sioux Dakota Gros Ventre Gros Ventre West Central NQ13 140 Plains Sioux Dakota Miniconju Miniconju West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Santee Santee West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Teton Teton West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Yankton Yankton West Central NQ11 Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Government Documents and Publications First Nations Era 3-10-2017 2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810" (2017). Government Documents and Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the First Nations Era at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government Documents and Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken and John R. Johnson March 2005 FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP, INC. 2727 Del Rio Place, Suite A, Davis, California, 95616 http://www.farwestern.com 530-756-3941 Prepared for Caltrans Contract No. 06A0148 & 06A0391 For individuals with sensory disabilities this document is available in alternate formats. Please call or write to: Gale Chew-Yep 2015 E. Shields, Suite 100 Fresno, CA 93726 (559) 243-3464 Voice CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. and John R. Johnson Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Submitted by: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. 2727 Del Rio Place, Davis, California, 95616 Submitted to: Valerie Levulett Environmental Branch California Department of Transportation, District 5 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 Contract No. -

Julia Pfeiffer Burns

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Julia Pfeiffer to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological Visitors from around the Burns diversity, protecting its most valued natural and cultural resources, and creating opportunities world revere the natural for high-quality outdoor recreation. State Park beauty of the park’s rugged coastline, panoramic views, California State Parks supports equal access. crashing surf and Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who need assistance should contact the Big Sur sparkling waters. Station at (831) 649-2836. This publication is available in alternate formats by contacting: CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369. (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Discover the many states of California.™ SaveTheRedwoods.org/csp Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park 11 miles south of Big Sur on Highway 1 Big Sur, CA 93920 (831) 649-2836 www.parks.ca.gov/jpb Julia Pfeiffer Burns photo courtesy of Big Sur Historical Society © 2011 California State Parks J ulia Pfeiffer Burns State Park including the McWay and Partington dropping nearly vertically to shore offers a dramatic meeting families. Homesteaders were provide habitat for many sensitive aquatic of land and sea—attracting largely self-suffcient—making and terrestrial species. visitors, writers, artists and a living as loggers, tanoak Three perennial creeks fow through the photographers from around harvesters or ranchers by using park; Anderson, Partington and McWay the world. -

Genetics, Linguistics, and Prehistoric Migrations: an Analysis of California Indian Mitochondrial DNA Lineages

Journal of California and Great Basin Anttiropology | Vol, 26, No, 1 (2006) | pp 33-64 Genetics, Linguistics, and Prehistoric Migrations: An Analysis of California Indian Mitochondrial DNA Lineages JOHN R. JOHNSON Department of Anthropology, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History 2559 Puesta del Sol, Santa Barbara, CA 93105 JOSEPH G. LORENZ Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Coriell Institute for Medical Research 403 Haddon Avenue, Camden, NJ 08103 The advent of mitochondrial DNA analysis makes possible the study of past migrations among California Indians through the study of genetic similarities and differences. Four scenarios of language change correlate with observable genetic patterns: (1) initial colonization followed by gradual changes due to isolation; (2) population replacement; (3) elite dominance; and (4) intermarriage between adjacent groups. A total of 126 mtDNA samples were provided by contemporary California Indian descendants whose maternal lineages were traced back to original eighteenth and nineteenth century sociolinguistic groups using mission records and other ethnohistoric sources. In particular, those groups belonging to three language families (Chumashan, Uto-Aztecan, and Yokutsan) encompassed enough samples to make meaningful comparisons. The four predominant mtDNA haplogroups found among American Indians (A, B, C, and D) were distributed differently among populations belonging to these language families in California. Examination of the distribution of particular haplotypes within each haplogroup further elucidated the separate population histories of these three language families. The expansions of Yokutsan and Uto-Aztecan groups into their respective homelands are evident in the structure of genetic relationships within haplogroup diagrams. The ancient presence of Chumashan peoples in the Santa Barbara Channel region can be inferred from the presence of a number of haplotypes arrayed along a chain-like branch derived from the founding haplotype within Haplogroup A. -

California-Nevada Region

Research Guides for both historic and modern Native Communities relating to records held at the National Archives California Nevada Introduction Page Introduction Page Historic Native Communities Historic Native Communities Modern Native Communities Modern Native Communities Sample Document Beginning of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the U.S. Government and the Kahwea, San Luis Rey, and Cocomcahra Indians. Signed at the Village of Temecula, California, 1/5/1852. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/55030733 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities California Native Communities To perform a search of more general records of California’s Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog, use Advanced Search. Enter California in the search box and 75 in the Record Group box (Bureau of Indian Affairs). There are several great resources available for general information and material for kids about the Native People of California, such as the Native Languages and National Museum of the American Indian websites. Type California into the main search box for both. Related state agencies and universities may also hold records or information about these communities. Examples might include the California State Archives, the Online Archive of California, and the University of California Santa Barbara Native American Collections. Historic California Native Communities Federally Recognized Native Communities in California (2018) Sample Document Map of Selected Site for Indian Reservation in Mendocino County, California, 7/30/1856. National Archives: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/50926106 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities Historic California Native Communities For a map of historic language areas in California, see Native Languages. -

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park 47225 Highway 1 Big Sur, CA 93920 (831) 667-2315 • Big Sur River © 2013 California State Parks (Rev

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is feiffer Big Sur Pfeiffer to provide for the health, inspiration and P education of the people of California by helping State Park is loved Big Sur to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological diversity, protecting its most valued natural and cultural resources, and creating opportunities for the serenity of its State Park for high-quality outdoor recreation. forests and the pristine, fragile beauty of the Big Sur River as it meanders California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who through the park. need assistance should contact the park at (831) 667-2315. If you need this publication in an alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov SaveTheRedwoods.org/csp Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park 47225 Highway 1 Big Sur, CA 93920 (831) 667-2315 • www.parks.ca.gov/pbssp Big Sur River © 2013 California State Parks (Rev. 2015) O n the western slope of the Santa Big Sur Settlers In the early 20th century, a developer Lucia Mountains, the peaks of Pfeiffer Big In 1834, Governor José Figueroa granted offered to buy some of John Pfeiffer’s land, Sur State Park tower high above the Big acreage to Juan Bautista Alvarado. planning to build a subdivision. Pfeiffer Sur River Gorge. This is a place where the Alvarado’s El Sur Rancho stretched from the refused.