An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

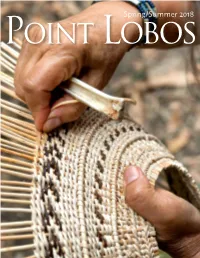

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Subsequent Initial Study of Environmental Impact

Cayucos Sanitary District 200 Ash Avenue Cayucos CA 93430 www.cayucossd.org • 805-773-4658 Cayucos Sustainable Water Project (CSWP) Subsequent Mitigated Negative Declaration for the Estero Marine Terminal Ocean Outfall Project Component Subsequent Initial Study of Environmental Impact I. ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINATION FORM 1. Project Title: Cayucos Sustainable Water Project Ocean Outfall 2. Lead Agency Name and Address: Cayucos Sanitary District 200 Ash Avenue / PO Box 333 Cayucos CA 93430 3. Contact Person and Phone Number: David Foote, c/o firma, (805) 781-9800 4. Project Location: Chevron Estero Marine Terminal 4000 Highway 1, Morro Bay, California 93442 5. Project Sponsor's Name and Address: Cayucos Sanitary District 200 Ash Avenue / PO Box 333 Cayucos CA 93430 6. General Plan Designation: The proposed pipeline tie-in site is designated Agriculture. The effluent pipeline conveyances are within public right-of-way (State Route 1) and Waters of the U.S. and State. 7. Zoning: Agriculture (County) and Open Area I/PD (City of Morro Bay west of State Route 1 and the mean high tide line) Cayucos Sustainable Water Project Ocean Outfall Initial Environmental Study Final January 2019 1 Cayucos Sanitary District 200 Ash Avenue Cayucos CA 93430 www.cayucossd.org • 805-773-4658 Cayucos Sustainable Water Project (CSWP) Subsequent Mitigated Negative Declaration for the Estero Marine Terminal Ocean Outfall Project Component 8. Project Description & Regulatory and Environmental setting LOCATION AND BACKGROUND The Project consists of the reuse of an existing ocean conveyance pipe for treated effluent disposal from the proposed and permitted Cayucos Sustainable Water Project’s (CSWP) Water Resource Recovery Facility (WRRF) by the Cayucos Sanitary District (CSD). -

April 1999 SCREE

January, 2001 Peak Climbing Section, Loma Prieta Chapter, Sierra Club Vol. 35 No. 1 World Wide Web Address: http://www.sierraclub.org/chapters/lomaprieta/pcs Next General Meeting 2001 Publicity Committee Date: Tuesday, January 9 The PCS Publicity Committee for the year 2001 is the following: Time: 7:30 PM Mailings: Paul Vlasveld Listmaster: Steve Eckert Program: Annapurna III, Southwest Buttress Webmaster: Jim Curl In October 1978 a team of people including Ann Scree Editor: Bob Bynum Reynolds made their way to Annapurna III with the I will announce the various e-mail addresses and contact objective of climbing the southwest buttress. information once I get that straightened out. Avalanche conditions on the mountain forced them to We can also use more help with the printing and mailing. If you are interested, please contact me. rethink their route and a line up the west face was chosen. Join us for a slide show by Ann Reynolds • Rick Booth, PCS PubComm Chair recounting this journey. A $2 donation is requested for the slide show. Farewell As Webmaster Location Peninsula Conservation Center 3921 Back in 1994, when the world wide web was young, Silicon East Bayshore Rd, Palo Alto, CA Graphics CEO Ed McCracken instructed all employees that the Directions: From 101: Exit at San Antonio Road, web was our future. He arranged to provide an internet server on the SGI site to be used for employees personal sites and for Go East to the first traffic light, Turn community service pages. I jumped at the opportunity, and left and follow Bayshore Rd to the without stopping to obtain permission from the Sierra Club, I PCC on the corner of Corporation created the first PCS web site on the SGI server. -

AB3030 Groundwater Management Plan

FINALFINAL AB3030 Groundwater Management Plan Prepared for Wheeler Ridge-Maricopa Water Storage District November 2007 Todd Engineers with Kennedy/Jenks Consultants FINAL AB3030 Groundwater Management Plan Wheeler Ridge-Maricopa Water Storage District Kern County, California Prepared for: Wheeler Ridge-Maricopa Water Storage District 12109 Highway 166 Bakersfield, CA 93313 Prepared by: Todd Engineers 2200 Powell Street, Suite 225 Emeryville, CA 94608 with Kennedy/Jenks Consultants 1000 Hill Road, Suite 200 Ventura, CA 93003-4455 November 2007 Table of Contents List of Tables....................................................................................................................... v List of Figures..................................................................................................................... v List of Appendices............................................................................................................... v Executive Summary...................................................................................................... ES-1 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................1 1.1. Background......................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Goals and Objectives of the Plan........................................................................ 2 1.3. Public Participation............................................................................................ -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Thomas L. Davis & Jay S. Namson

S KERN A FRONT N ROUND 1' McDONALD RIO BRAVO POSO MOUNTAIN ANTICLINE CREEK Thomas L. Davis & Jay S. Namson J 3' SOUTH SAN JOAQUINROSEDALE VALLEY KERN U RIVER BELRIDGE SEVENTH RANCH A STANDARD N CHICO-MARTINEZ GEOLOGISTS BOWERBANK KERN BLUFF GREELEY F ROSEDALE LA PANZA RANGE A U ANT HILL CALDERS L FRUITVALE CORNER 592 Poli St., Ventura, CA 93001 T ESTERO CYMRIC NORTHEAST H Ph:(805) 653-2435, Fax:(805) 653-2459 email:[email protected] BAY ENGLISH COLONY BAKERSFIELD EDISON U CARRIZO PLAIN EAST TEMBLOR GOOSLOO UNION WEST BELLEVUE BELLEVUE E S AVENUE R McCLUNG A TEMBLOR RANCH H N STRAND U McKITTRICK TEMBLOR CANAL Southern California Cross Section Study Map E STOCKDALE R A RAILROAD GAP EDISON R O N IN F C A D KERN SUMNER SAN LUIS VALLEY O U CANFIELD Showing 2012 AAPG Annual Mtg Field Trip Stops N L R NORTH RANCH A T BELGIAN ELK HILLS ANTICLINE COLES LEVEE D B E TEN SAN LUIS A - N C I A ASPHALTO SECTION A C G BUENA VISTA VALLEYELK HILLS (Field Trip #5, April 21 & 22, 2012) SODA SOUTH OBISPO IM H S S 4 I R COLES Field Trip Stop IE M P 5' LAKESIDE R IN LAKE E LEVEE MOUNTAIN N E G C T F VIEW PT. SAN LUIS O N A F R E U A U A LT I E F T SOUTH LAKESIDE SANTA LUCIA RANGE A S U MIDWAY-SUNSET A U P S C BUENA VISTA HILLS L F L A ARROYO GRANDE T U A BUENA T T S BUENA VISTA Y U S VISTA A L PALOMA H M T From: thomasldavisgeologist.com; go to downloads F LAKE U A A TEHACHAPI MOUNTAINS A CARRIZO PLAIN U BED F 4' L T T W S A W RANGE KERN LAKE L N U M U E H BED Date: May 24. -

4. Environmental Impact Analysis 4. Cultural Resources

4. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ANALYSIS 4. CULTURAL RESOURCES 4.4.1 INTRODUCTION The following section addresses the proposed Project’s potential to result in significant impacts upon cultural resources, including archaeological, paleontological and historic resources. On September 20, 2013, the South Central Coastal Information Center (SCCIC) and the Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County were contacted to conduct a records search for cultural resources within the Project Site at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street and immediate Project vicinity. The analysis presented below is based on the record search results provided from the SCCIC, dated October 2, 2013, and written correspondence from The Vertebrate Paleontology Department at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, dated October 18, 2013. Correspondences from both agencies are included in Appendix E to this Draft EIR. 4.4.2 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING Description of the Study Area The Project Site is located at the intersection of Lyons Avenue and Railroad Avenue and extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University and northwest towards the intersection of 12th Street and Arch Street. The Project Site also includes the closure of an at- grade crossing at the intersection of Railroad Avenue and 13th Street. The portion of the Project Site that extends eastward towards the General Plan alignment for Dockweiler Drive towards The Master’s University is located in an area of primarily undeveloped land within the city limits of Santa Clarita. -

On Numeral Complexity in Hunter-Gatherer Languages

On numeral complexity in hunter-gatherer languages PATIENCE EPPS, CLAIRE BOWERN, CYNTHIA A. HANSEN, JANE H. HILL, and JASON ZENTZ Abstract Numerals vary extensively across the world’s languages, ranging from no pre- cise numeral terms to practically infinite limits. Particularly of interest is the category of “small” or low-limit numeral systems; these are often associated with hunter-gatherer groups, but this connection has not yet been demonstrated by a systematic study. Here we present the results of a wide-scale survey of hunter-gatherer numerals. We compare these to agriculturalist languages in the same regions, and consider them against the broader typological backdrop of contemporary numeral systems in the world’s languages. We find that cor- relations with subsistence pattern are relatively weak, but that numeral trends are clearly areal. Keywords: borrowing, hunter-gatherers, linguistic area, number systems, nu- merals 1. Introduction Numerals are intriguing as a linguistic category: they are lexical elements on the one hand, but on the other they are effectively grammatical in that they may involve a generative system to derive higher values, and they interact with grammatical systems of quantification. Numeral systems are particularly note- worthy for their considerable crosslinguistic variation, such that languages may range from having no precise numeral terms at all to having systems whose limits are practically infinite. As Andersen (2005: 26) points out, numerals are thus a “liminal” linguistic category that is subject to cultural elaboration. Recent work has called attention to this variation among numeral systems, particularly with reference to systems having very low limits (for example, see Evans & Levinson 2009, D. -

Meroz-Plank Canoe-Edited1 Without Bold Ital

UC Berkeley Survey Reports, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages Title The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1977t6ww Author Meroz, Yoram Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Plank Canoe of Southern California: Not a Polynesian Import, but a Local Innovation YORAM MEROZ By nearly a millennium ago, Polynesians had settled most of the habitable islands of the eastern Pacific, as far east as Easter Island and as far north as Hawai‘i, after journeys of thousands of kilometers across open water. It is reasonable to ask whether Polynesian voyagers traveled thousands of kilometers more and reached the Americas. Despite much research and speculation over the past two centuries, evidence of contact between Polynesia and the Americas is scant. At present, it is generally accepted that Polynesians did reach South America, largely on the basis of the presence of the sweet potato, an American cultivar, in prehistoric East Polynesia. More such evidence would be significant and exciting; however, no other argument for such contact is currently free of uncertainty or controversy.1 In a separate debate, archaeologists and ethnologists have been disputing the rise of the unusually complex society of the Chumash of Southern California. Chumash social complexity was closely associated with the development of the plank-built canoe (Hudson et al. 1978), a unique technological and cultural complex, whose origins remain obscure (Gamble 2002). In a recent series of papers, Terry Jones and Kathryn Klar present what they claim is linguistic, archaeological, and ethnographical evidence for prehistoric contact from Polynesia to the Americas (Jones and Klar 2005, Klar and Jones 2005). -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS of CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley

THE VOWEL SYSTEMS OF CALIFORNIA HOKAN1 Jeff Good University of California, Berkeley Unlike the consonants, the vowels of Hokan are remarkably conservative. —Haas (1963:44) The evidence as I view it points to a 3-vowel proto-system consisting of the apex vowels *i, *a, *u. —Silver (1976:197) I am not willing, however, to concede that this suggests [Proto-Hokan] had just three vowels. The issue is open, though, and I could change my mind. —Kaufman (1988:105) 1. INTRODUCTION. The central question that this paper attempts to address is the motivation for the statements given above. Specifically, assuming there was a Proto-Hokan, what evidence is there for the shape of its vowel system? With the exception of Kaufman’s somewhat equivocal statement above, the general (but basically unsupported) verdict has been that Proto-Hokan had three vowels, *i, *a, and *u. This conclusion dates back to at least Sapir (1917, 1920, 1925) who implies a three-vowel system in his reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms. However, as far as I am aware, no one has carefully articulated why they think the Proto-Hokan system should have been of one form instead of another (though Kaufman (1988) does discuss some of his reasons).2 Furthermore, while reconstructions of Proto-Hokan forms exist, it has not yet been possible to provide a detailed analysis of the sound changes required to relate reconstructed forms to attested forms. As a result, even though the reconstructions themselves are valuable, they cannot serve as a strong argument for the particular proto vowel system they implicitly or explicitly assume. -

Visitors Map

VISITORS MAP Explore Paso Robles Backroads TheOriginalRoadTrip.com VISITORS MAP Discover Wineries and vineyards Monterey Bay Carmel-by-the-Sea Alma Rosa Winery Wine Tasting 181-C Industrial Way Wine REGION Enjoy our local wines at Buellton 93427 16 tasting rooms – all walkable 805.688.9090 CarmelCalifornia.com/wine AlmaRosaWinery.com Hit the trail – the wine trail. California’s Central Coast is a Eden Rift Ampelos Cellars dream destination for wine lovers, with more than a dozen 10034 Cienega Rd. 312 N. 9th St. Hollister 95023 Lompoc 93436 American Viticultural Areas, or AVAs, producing some of 831.636.1991 805.736.9957 REGION REGION EdenRift.com AmpelosCellars.net California’s most popular wines. Choose among hundreds Elephant Seals, San Simeon Manzoni Cellars Brick Barn Wine Estate of Central Coast wineries to sample California wines Wine Tasting Room 795 W. Hwy. 246 Hampton Court on 7th Ave., Buellton 93427 including Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Zinfandel. With its btw San Carlos & Dolores St. 805.686.1208 Explore California’s Central Coast TRAVEL WELL endless variety, the Central Coast is California wine county Carmel by the Sea 93921 BrickBarnWineEstate.com Discover Harvey Bear 831.620.6541 monterey baY monterey baY you can visit again and again. ManzoniWines.com barbarA santa Ranch County Park Explore 350 miles of the world’s most beautiful coastline • Be an altruistic traveler by visiting Welcome Centers, Wineries of Santa Clara Valley Award-winning, meet the Vintner between San Francisco and Los Angeles. supporting the preservation of every destination, staying Enjoy hiking, biking, scenery 408.842.6436 on designated paths, and respecting others and wildlife.