Supplemental Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

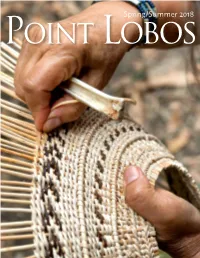

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

The Taxonomic Status of Gladiolus Illyricus (Iridaceae) in Britain

The Taxonomic Status of Gladiolus illyricus (Iridaceae) in Britain Aeron Buchanan Supervisor: Fred Rumsey, Natural History Museum, London A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science of Imperial College, London Abstract First noticed officially in Britain in 1855, Gladiolus illyricus (Koch) presents an interesting taxonomic and biogeographical challenge: whether or not this isolated northern population should be recognized as a separate sub-species. Fundamental conservation issues rest on the outcome. Here, the investigation into the relationship of the G. illyricus plants of the New Forest, Hampshire, to Gladiolus species across Europe, northern Africa and the middle east is initiated. Two chloroplast regions, one in trnL–trnF and the other across psbA–trnH have been sequenced for 42 speci- mens of G. illyricus, G. communis, G. italicus, G. atroviolaceus, G. triphyllos and G. anatolicus. Phylogenetic and biogeographical treatments support the notion of an east–west genetic gradation along the Mediterranean. Iberia particularly appears as a zone of high hybridization potential and the source of the New Forest population. Alignment with sequences obtained from GenBank give strong support to the classic taxonomy of Gladiolus being monophyletic in its sub-family, Ixioideae. Comments on these chloroplast regions for barcoding are also given. In conclusion, the genetic localization of Britain’s G. illyricus population as an extremity haplotype suggests that it could well deserve sub-species status. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Background 4 3 Materials and Methods 8 4 Results and Discussion 15 5 Conclusions 26 Appendices 28 References 56 1. Introduction G. illyricus in Britain Figure 1: G. -

California's Native Ferns

CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE FERNS A survey of our most common ferns and fern relatives Native ferns come in many sizes and live in many habitats • Besides living in shady woodlands and forests, ferns occur in ponds, by streams, in vernal pools, in rock outcrops, and even in desert mountains • Ferns are identified by producing fiddleheads, the new coiled up fronds, in spring, and • Spring from underground stems called rhizomes, and • Produce spores on the backside of fronds in spore sacs, arranged in clusters called sori (singular sorus) Although ferns belong to families just like other plants, the families are often difficult to identify • Families include the brake-fern family (Pteridaceae), the polypody family (Polypodiaceae), the wood fern family (Dryopteridaceae), the blechnum fern family (Blechnaceae), and several others • We’ll study ferns according to their habitat, starting with species that live in shaded places, then moving on to rock ferns, and finally water ferns Ferns from moist shade such as redwood forests are sometimes evergreen, but also often winter dormant. Here you see the evergreen sword fern Polystichum munitum Note that sword fern has once-divided fronds. Other features include swordlike pinnae and round sori Sword fern forms a handsome coarse ground cover under redwoods and other coastal conifers A sword fern relative, Dudley’s shield fern (Polystichum dudleyi) differs by having twice-divided pinnae. Details of the sori are similar to sword fern Deer fern, Blechnum spicant, is a smaller fern than sword fern, living in constantly moist habitats Deer fern is identified by having separate and different looking sterile fronds and fertile fronds as seen in the previous image. -

Checklist of Common Native Plants the Diversity of Acadia National Park Is Refl Ected in Its Plant Life; More Than 1,100 Plant Species Are Found Here

National Park Service Acadia U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Checklist of Common Native Plants The diversity of Acadia National Park is refl ected in its plant life; more than 1,100 plant species are found here. This checklist groups the park’s most common plants into the communities where they are typically found. The plant’s growth form is indicated by “t” for trees and “s” for shrubs. To identify unfamiliar plants, consult a fi eld guide or visit the Wild Gardens of Acadia at Sieur de Monts Spring, where more than 400 plants are labeled and displayed in their habitats. All plants within Acadia National Park are protected. Please help protect the park’s fragile beauty by leaving plants in the condition that you fi nd them. Deciduous Woods ash, white t Fraxinus americana maple, mountain t Acer spicatum aspen, big-toothed t Populus grandidentata maple, red t Acer rubrum aspen, trembling t Populus tremuloides maple, striped t Acer pensylvanicum aster, large-leaved Aster macrophyllus maple, sugar t Acer saccharum beech, American t Fagus grandifolia mayfl ower, Canada Maianthemum canadense birch, paper t Betula papyrifera oak, red t Quercus rubra birch, yellow t Betula alleghaniesis pine, white t Pinus strobus blueberry, low sweet s Vaccinium angustifolium pyrola, round-leaved Pyrola americana bunchberry Cornus canadensis sarsaparilla, wild Aralia nudicaulis bush-honeysuckle s Diervilla lonicera saxifrage, early Saxifraga virginiensis cherry, pin t Prunus pensylvanica shadbush or serviceberry s,t Amelanchier spp. cherry, choke t Prunus virginiana Solomon’s seal, false Maianthemum racemosum elder, red-berried or s Sambucus racemosa ssp. -

People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: a Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2012 People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Deborah Confer University of Washington Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Confer, Deborah, "People of Snowy Mountain, People of the River: A Multi-Agency Ethnographic Overview and Compendium Relating to Tribes Associated with Clark County, Nevada" (2012). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 98. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/98 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series National Park Service Publication Number 2012-01 U.S. Department of the Interior PEOPLE OF SNOWY MOUNTAIN, PEOPLE OF THE RIVER: A MULTI-AGENCY ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW AND COMPENDIUM RELATING TO TRIBES ASSOCIATED WITH CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA 2012 Douglas Deur, Ph.D. and Deborah Confer LAKE MEAD AND BLACK CANYON Doc Searls Photo, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59b7c0n9 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Cohen, Bill Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Antliropology Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-34 (1987). Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California BILL COHEN, 746 Westholme Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024. OANDPAINTINGS created by native south were similar in technique to the more elab ern Californians were sacred cosmological orate versions of the Navajo, they are less maps of the universe used primarily for the well known. This is because the Spanish moral instruction of young participants in a proscribed the religion in which they were psychedelic puberty ceremony. At other used and the modified native culture that times and places, the same constructions followed it was exterminated by the 1860s. could be the focus of other community ritu Southern California sandpaintings are among als, such as burials of cult participants, the rarest examples of aboriginal material ordeals associated with coming of age rites, culture because of the extreme secrecy in or vital elements in secret magical acts of which they were made, the fragility of the vengeance. The "paintings" are more accur materials employed, and the requirement that ately described as circular drawings made on the work be destroyed at the conclusion of the ground with colored earth and seeds, at the ceremony for which it was reproduced. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Cara Rachelle Monroe Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Jochim, Chair Professor Lynn Gamble Professor Michael Glassow Adjunct Professor John R. Johnson September 2014 The dissertation of Cara Rachelle Monroe is approved. ____________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble ____________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow ____________________________________________ John R. Johnson ____________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim, Committee Chair September 2014 Correlating Biological Relationships, Social Inequality, and Population Movement among Prehistoric California Foragers: Ancient Human DNA Analysis from CA-SCL-38 (Yukisma Site). Copyright © 2014 by Cara Rahelle Monroe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing this dissertation has been an intellectual journey filled with difficulties, but ultimately rewarding in unexpected ways. I am leaving graduate school, albeit later than expected, as a more dedicated and experienced scientist who has adopted a four field anthropological research approach. This was not only the result of the mentorships and the education I received from the University of California-Santa Barbara’s Anthropology department, but also from friends -

Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area

Crashing waves, redwoods and historic sites Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area Some of the most beautiful sights in California can be found in Monterey area California State Parks. Rocky cliffs, crashing waves, redwood trees, and historic sites are within an easy drive of each other. "When you look at the diversity of state parks within the Monterey District area, you begin to realize that there is something for everyone - recreational activities, scenic beauty, natural and cultural history sites, and educational programs,” said Dave Schaechtele, State Parks Monterey District Public Information Officer. “There are great places to have fun with families and friends, and peaceful and inspirational settings that are sure to bring out the poet, writer, photographer, or artist in you. Some people return to their favorite state parks, year-after-year, while others venture out and discover some new and wonderful places that are then added to their 'favorites' list." State Parks in the area include: Limekiln State Park, 54 miles south of Carmel off Highway One and two miles south of the town of Lucia, features vistas of the Big Sur coast, redwoods, and the remains of historic limekilns. The Rockland Lime and Lumber Company built these rock and steel furnaces in 1887 to cook the limestone mined from the canyon walls. The 711-acre park allows visitors an opportunity to enjoy the atmosphere of Big Sur’s southern coast. The park has the only safe access to the shoreline along this section of cast. For reservations at the park’s 36 campsites, call ReserveAmerica at (800) 444- PARK (7275). -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated.