An Acoustic Investigation of Vowel Variation in Gitksan by Kyra Ann Fortier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theoretical Aspects of Gitksan Phonology by Jason Camy Brown B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2000 M.A., California St

Theoretical Aspects of Gitksan Phonology by Jason Camy Brown B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2000 M.A., California State University, Fresno, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Linguistics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2008 © Jason Camy Brown, 2008 Abstract This thesis deals with the phonology of Gitksan, a Tsimshianic language spoken in northern British Columbia, Canada. The claim of this thesis is that Gitksan exhibits several gradient phonological restrictions on consonantal cooccurrence that hold over the lexicon. There is a gradient restriction on homorganic consonants, and within homorganic pairs, there is a gradient restriction on major class and manner features. It is claimed that these restrictions are due to a generalized OCP effect in the grammar, and that this effect can be relativized to subsidiary features, such as place, manner, etc. It is argued that these types of effects are best analyzed with the system of weighted constraints employed in Harmonic Grammar (Legendre et al. 1990, Smolensky & Legendre 2006). It is also claimed that Gitksan exhibits a gradient assimilatory effect among specific consonants. This type of effect is rare, and is unexpected given the general conditions of dissimilation. One such effect is the frequency of both pulmonic pairs of consonants and ejective pairs of consonants, which occur at rates higher than expected by chance. Another is the occurrence of uvular-uvular and velar-velar pairs of consonants, which also occur at rates higher than chance. This pattern is somewhat surprising, as there is a gradient prohibition on cooccurring pairs of dorsal consonants. -

Land Use Plan 2019

KITSELAS FIRST NATION LAND USE PLAN 2019 DRAFT The Land Use Plan is a DRAFT living document and must be reviewed as part of all decision-making processes on Kitselas’ Reserve lands. This is to ensure that any proposed future decisions related to the use of land are consistent with the Plan. Any decisions related to new development or expansion or relocation of existing development must adhere to the Land Use Plan. Examples of projects that would require input from the Land Use Plan include, but may not be limited to: Residential development (homes and subdivisions) Commercial development Industrial development Infrastructure development Community facilities Resource extraction activities (i.e. forestry and mining) DRAFT Preamble his Land Use Plan will be interpreted in accordance with the culture, traditions and customs of Kitselas First Nation (KFN). The preamble for the Kitselas Reserve Lands Management Act (posted Ton the Kitselas First Nation website) provided guidance for the development of the Land Use Plan. The Act sets out the principles and legislative and administrative structures that apply to Kitselas land and by which the Nation exercises authority over this land. The preamble to the Kitselas Reserve Lands Management Act is derived from the Men of M’deek, the oral translation of the Kitselas people as described by Walter Wright. It states: “The Kitselas People have occupied and benefited Wise Men delved deeply to find its cause. At from their home lands since time out of memory last, satisfied they had learned that which they and govern their lives and lands through a had sought for, they said, “The action that lies system of laws and law making based on the at the root of this difficulty is wrong. -

Limxhl Hlgu Wo'omhlxw Song of the Newborn Knowledge and Stories

Limxhl Hlgu Wo'omhlxw Song of the Newborn Knowledge and Stories Surrounding Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Newborn A Collaborative Language Project by Catherine Dworak B.A., Concordia University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Linguistics c Catherine Dworak, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Limxhl Hlgu Wo'omhlxw Song of the Newborn Knowledge and Stories Surrounding Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Newborn A Collaborative Language Project by Catherine Dworak B.A., Concordia University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Suzanne Urbanczyk, Supervisor Department of Linguistics Dr. Leslie Butt, Outside Member Department of Anthropology ii Abstract The Limxhl Hlgu Wo'omhlxw (Song of the Newborn) project is situated on Lax Yipxwhl Gitxsan (Gitxsan Territory) and embraces a decolonizing and Indigenist (Wilson, 2007) methodology. The project is a collaboration between Catherine Dworak (me), the graduate student, and Dr. M.J. Smith, educator and Gitxsan storyteller. We partnered with three Gitxsan Elders to learn about the language of pregnancy, childbirth, and life with a newborn. In agreeing to work with us, the Elders honoured us by sharing some of their knowledge and life experiences with us. The thesis begins with three chapters that provide background information re- garding the Gitxsan language and territory, how I came to be involved in the project, and the traditional seasonal round and laws related to women in transitional periods. The thesis then details the research process that emerged from the project. -

An Historic Event in the Political Economy of the Tsimshian : Information on the Ownership of the Zimacord District* JAMES ANDREW Mcdonald

An Historic Event in the Political Economy of the Tsimshian : Information on the Ownership of the Zimacord District* JAMES ANDREW McDONALD This paper reconstructs and presents a bit of ethnographic information that is based upon a piece of the oral history of the Tsimshian people,, a society native to what is now northwestern British Columbia. The value of the history lies not only in the events described, but also in the illustra tion it provides of relationships between a set of houses in two neighbour ing villages prior to the Canadian Confederation. In the history can be seen several aspects of the old property relationships under which the Tsimshian lived, as well as an outline of their social organization. Anthropologically understood, property is a socially embedded defini tion of relationships between persons within a society. The property piece itself, not necessarily a material object, is a mediation of these relation ships, a focus of attention for how persons and groups are to relate to one another. Thus, property defines the rights and obligations people and groups have to each other, setting the limits to the use of the property while demanding adherence to the dominant mores of the community, and re-establishing these relationships in the process. Any particular form of property is always stamped by the impression of the society in which it exists and by which it is defined. In the story about the Zimacord District lies the mark of Tsimshian society attempt ing to re-assert proper practices towards territorial resource property, and to justify a particular arrangement of ownership, in this case that of the acquisition of property by one group from another. -

Linguistics 181 Course Notes

Notes for Linguistics 181 Introductory Linguistics for Language Revitalization with a focus on Nuuchahnulth Janet Leonard and Adam Werle 2010–2018 Contents Handout 1. What is linguistics? ............................................1 Handout 2. A history of linguistics .......................................3 Handout 3. Language families of British Columbia ..............5 Handout 4. Language learning..............................................7 Handout 5. Vowels................................................................9 Handout 6. Consonants.......................................................11 Handout 7. Alphabets .........................................................13 Handout 8. Phonemes.........................................................15 Handout 9. Word-building..................................................17 Handout 10. Interlinear analysis.........................................19 Handout 11. Sentence structure..........................................21 Handout 12. Aspect, tense, and mood ................................23 References...........................................................................25 Endnotes .............................................................................26 i Notes for Linguistics 181: Introductory Linguistics for Language Revitalization, with a focus on Nuuchahnulth (CC BY) 2010–2018 Janet Leonard and Adam Werle University of Victoria These notes were written by Janet Leonard and Adam Werle in 2010 for University of Victoria Linguistics 181, focusing on SENĆOŦEN -

Declaration of the Kitsumkalum Indian Band of the Tsimshian Nation of Aboriginal Title and Rights to Prince Rupert Harbour and Surrounding Coastal Areas

DECLARATION OF THE KITSUMKALUM INDIAN BAND OF THE TSIMSHIAN NATION OF ABORIGINAL TITLE AND RIGHTS TO PRINCE RUPERT HARBOUR AND SURROUNDING COASTAL AREAS I. Introduction This declaration is made by the Elected and Hereditary Chiefs of the Kitsumkalum Indian Band (“Kitsumkalum”) on behalf of all Kitsumkalum. Kitsumkalum is a strong, proud part of the Tsimshian Nation. We take exception to attempts to deny us our rightful place within the Tsimshian Nation, and to deny us our rightful place on the coast, with its sites and resources that are an integral part of who we are. This denial is more than an attempt to separate us from our lands and resources, it is an assault on who we are as people. We are supposed to be moving forward with Canada and British Columbia in a spirit of recognition and reconciliation. Instead, we are met with denial and resistance. In this declaration, we once again assert who we are and what is ours. We are a part of the Tsimshian Nation that exclusively occupied the Prince Rupert Harbour and surrounding coastal and inland areas prior to and as of 1846. Within that area, we hold exclusive ownership over and responsibity for specific sites in accordance with ayaawx, Tsimshian Law. We have aboriginal rights to fish, harvest, gather and engage in cultural and spiritual activities throughout the coastal part of our territory. There is much at stake – in particular with a Liquefied Natural Gas (“LNG”) industry at our doorstep. It is only through recognition on the part of Canada and British Columbia of our rights and title and an acknowledgement of your legal obligations to consult meaningfully with us that we can move forward in a spirit of mutual respect and work to achieve results for our mutual benefit. -

Tsimshian Wil'naat'ał and Society

Tsimshian Wil’naat’ał and Society: Historicising Tsimshian Social Organization James A. McDonald Introduction ot far from Gitxaała are the people who live inside the mists of the Skeena River. Connected to Gitxaała by the familial ties of kinship and chiefly designs, theN eleven Aboriginal communities of the lower Skeena River also are part of the Tsimshian Nation. The prevailing understanding of Tsimshian social organization has long been clouded in a fog of colonialism. The resulting interpretation of the indigenous prop- erty relations marches along with the new colonial order but is out of step with values expressed in the teachings of the wilgagoosk – the wise ones who archived their knowledge in the historical narratives called adaawx and other oral sources. This chapter reviews traditional and contemporary Tsimshian social structures to argue that the land owning House (Waap1) and Clan (Wil’naat’ał) have been demoted in importance in favour of the residential and political communities of the tribe (galts’ap). Central to my argument is a critical analysis of the social importance of the contemporary Indian Reserve villages that is the basis of much political, cultural, and economic activity today. The perceived centrality of these settlements and their associated tribes in Tsimshian social structure has become a historical canon accepted by missionaries, politicians, civil servants, historians, geographers, archaeologists, and many “armchair” anthropologists. This assumption is a convention that loosens the Aboriginal ties to the land and resources and is attractive for the colonial society. It is a belief that has been normalized within the colonized worldview as the basis for relationships in civil society. -

Congrès De L'acl 2014 CLA Conference 2014

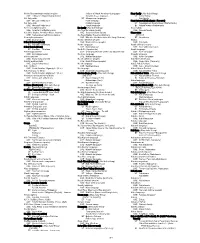

Congrès de l’ACL 2014 CLA Conference 2014 L’Association canadienne de linguistique tiendra son congrès de 2014 lors du !e Canadian Linguistic Association will hold its 2014 conference as part of the Congrès des sciences humaines à l'Université Brock, St. Catharines (ON), du Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences at Brock University, St. samedi 24 mai au lundi 26 mai 2014. Catharines, ON, from Saturday May 24 to Monday May 26, 2014. Programme dernière mise à jour: 17 mai 2014 | latest update: May 17, 2014 Samedi 24 mai | Saturday, May 24 Thistle 255 Thistle 256 Thistle 257 Acquisition (L1) Variation & changement | Variation & change Syntaxe | Syntax 9:00–9:30 Yvan Rose (MUN) Kazuya Bamba (Toronto) Tomokazu Takehisa (NUPALS) Interfaces entre domaines phonétique et phonologique dans !e interaction between impersonal re"exives and syntactic #ange Non-selected arguments and the ethical strategy l’acquisition de la phonologie 9:30–10:00 Marina Sherkina-Lieber (Carleton) Alena Barysevich (York) Carlos de Cuba (Calgary) Monolingual and bilingual #ildren’s production of Russian embedded Emergence des normes communautaires : cas de la variation lexicale In defense of the truncation hypothesis for main clause phenomena yes–no questions 10:00–10:30 Anna Frolova (Toronto) Philip Comeau (O!awa) & Anne-José Villeneuve (Toronto) Paul Poirier (Toronto) Développement de la transitivité verbale en russe L1 !e expression of future temporal reference in Picardie Fren# Malay/Indonesian voice and pseudo-incorporation 10:30–10:45 PAUSE | BREAK Thistle 255 Thistle 256 Thistle 257 Acquisition (L2+) Pragmatique | Pragmatics Syntaxe | Syntax 10:45–11:15 Johannes Knaus & Mary Grantham O’Brien (Calgary) Johannes Heim, Hermann Keupdjio, Zoe Wai-Man Lam, Adriana Julianne Doner (Toronto) Stress and morphology in second language production and processing Osa-Gómez & Martina Wiltschko (UBC) Dimensions of variation of the EPP How to do things with particles 11:15–11:45 Gabrielle Klassen & María-Cristina Cuervo (Toronto) E. -

Section 16.0 Background Information

KITSAULT MINE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Section 16.0 Background Information VE51988 KITSAULT MINE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS PART D – METLAKATLA INFORMATION REQUIREMENTS ........................................................ 16-1 16.0 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ......................................................................................... 16-2 16.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 16-2 16.2 Contact Information and Governance ..................................................................... 16-3 16.3 Territory and Reserves ............................................................................................ 16-4 16.3.1 Métis Nation ................................................................................................ 16-7 16.4 Ethnography ............................................................................................................ 16-7 16.4.1 Pre-Contact ................................................................................................ 16-7 16.4.2 Contact ....................................................................................................... 16-7 16.4.3 Post-Contact ............................................................................................... 16-8 16.5 Demographics ......................................................................................................... 16-8 16.6 Culture and Language ............................................................................................ -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Indians of North America—Languages Naar family (Not Subd Geog) USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine West (U.S.)—Languages UF Nahar family N-3 fatty acids NT Athapascan languages Narr family USE Omega-3 fatty acids Eyak language Naardermeer (Netherlands : Reserve) N-6 fatty acids Haida language UF Natuurgebied Naardermeer (Netherlands) USE Omega-6 fatty acids Tlingit language BT Natural areas—Netherlands N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na family (Not Subd Geog) Naas family USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Na Guardis Island (Spain) USE Nassau family N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) USE Guardia Island (Spain) Naassenes USE Native American Music Awards Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) [BT1437] N-acetylhomotaurine USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) BT Gnosticism USE Acamprosate Na-hsi (Chinese people) Nāatas N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi (Chinese people) USE Navayats BT Ranches—Montana Na-hsi language Naath (African people) N Bar Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi language USE Nuer (African people) BT Ranches—Montana Na Ih Es (Apache rite) Naath language N-benzylpiperazine USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) USE Nuer language USE Benzylpiperazine Na-Kara language Naaude language n-body problem USE Nakara language USE Ayiwo language USE Many-body problem Na-khi (Chinese people) Nab River (Germany) N-butyl methacrylate USE Naxi (Chinese people) USE Naab River (Germany) USE Butyl methacrylate Na-khi language Nabā, Jabal (Jordan) N.C. 12 (N.C.) USE Naxi language USE Nebo, Mount (Jordan) USE North Carolina -

Lax Kw'alaams Decision

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Citation: Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band v. Canada (Attorney General), 2008 BCSC 447 Date: 20080416 Docket: L023106 Registry: Vancouver 2008 BCSC 447 (CanLII) Between: The Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band, represented by Chief Councillor Garry Reece on his own behalf and on behalf of the members of the Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band, and others Plaintiffs And The Attorney General of Canada and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia Defendants Before: The Honourable Madam Justice Satanove Reasons for Judgment Lax Kw’alaams Indian Band v. Canada (Attorney General) Page 2 Counsel for the plaintiffs: John R. Rich F. Matthew Kirchner Kevin D. Lee Lisa C. Glowacki Kate M. Blomfield Kristy A. Pozniak Counsel for the defendant, James M. Mackenzie The Attorney General of Canada: Jack L. Wright John H. Russell Monika R. Bittel Thomas E. Bean Sheri-Lynn Vigneau Ji Won Yang 2008 BCSC 447 (CanLII) Erin M. Tully Kelly P. Keenan Counsel for the defendant, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of the Province of British Columbia: Keith J. Phillips Date and Place of Trial: November 20 – 24; 27 – 30, December 1; 4 – 8; 11 – 15, 2006. January 8 – 12; 15 – 19; 23 – 26, February 2; 5 – 9; 12 – 16; 19 – 23, March 12 – 16; 19 – 23; 26 – 30, April 2 – 5; 16 – 20; 23 – 27; 30, May 1 – 4; 14 – 18; 28 – 31, June 1; 4– 7; 11 – 15; 18 – 22; 25 – 27, August 9 – 10, September 24; 25; 27 – 28, October 1 – 5; 9; 11; 12 & 15, 2007. -

Ts'msyen Revolution: the Poetics and Politics of Reclaiming

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2015 Ts'msyen Revolution: The Poetics and Politics of Reclaiming Robin R. R. Gray University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Robin R. R., "Ts'msyen Revolution: The Poetics and Politics of Reclaiming" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 437. https://doi.org/10.7275/7247509.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/437 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TS’MSYEN REVOLUTION: THE POETICS AND POLITICS OF RECLAIMING A Dissertation Presented By ROBIN R. R. GRAY (T’UU’TK) Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2015 Department of Anthropology © Copyright by Robin R. R. Gray (T’uu’tk) 2015 All Rights Reserved TS’MSYEN REVOLUTION: THE POETICS AND POLITICS OF RECLAIMING A Dissertation Presented By ROBIN R. R. GRAY (T’UU’TK) Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________________ Jane Anderson, Chair _____________________________________________ Sonya Atalay, Chair _____________________________________________ Demetria Shabazz, Member __________________________________________ Thomas Leatherman, Department Chair Department of Anthropology DEDICATION To the Nine Allied Tribes and the people of Lax Kw’alaams—past, present and future.