Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lookout 2018-0809

The Lookout August - September 2018 Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Dedicated to the preservation, protection and enjoyment of the Forest Preserve http://www.adk-schenectady.org Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Board ELECTED OFFICERS LOOKOUT EDITOR: CHAIR: Mal Provost Stan Stoklosa 518-399-1565 518-383-3066 [email protected] [email protected] MEMBERSHIP: VICE-CHAIR: Mary Zawacki Vacant 914-373-8733 [email protected] SECRETARY: Jacque McGinn NORTHVILLE PLACID TRAIL: 518-438-0557 Mary MacDonald 79 Kenaware Avenue, Delmar, NY 12054 518-371-1293 [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: OUTINGS: Mike Brun Roy Keats 518-399-1021 518-370-0399 [email protected] [email protected] DIRECTOR: PRINTING/MAILING: Roy Keats Rich Vertigan 603-953-8782 518-381-9319 [email protected] [email protected] PROJECT COORDINATORS: PUBLICITY: Horst DeLorenzi Richard Wang 518-399-4615 518-399-3108 [email protected] [email protected] Jacque McGinn TRAILS: 518-438-0557 Norm Kuchar [email protected] 518-399-6243 [email protected] Jason Waters 518-369-5516 WEB MASTER: [email protected] Rich Vertigan 518-381-9319 APPOINTED MEMBERS [email protected] CONSERVATION: WHITEWATER: Mal Provost Ralph Pascale 518-399-1565 518-235-1614 [email protected] [email protected] INNINGS: YOUNG MEMBERS GROUP: Sally Dewes Dustin Wright 518-346-1761 603-953-8782 [email protected] [email protected] Dennis Wischman navigates Zoar Gap on the Deerfield River On the during a class on whitewater skills offered by Sally Dewes in cover June. -

Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

Prepared in Cooperation with the Water Resources Program of the Yakama Nation Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3315 Photograph showing Mount Adams andesitic stratovolcano and Signal Peak mafic shield volcano viewed westward from near Mill Creek Guard Station. Low-relief rocky meadows and modest forested ridges marked by scattered cinder cones and shields are common landforms in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. Mount Adams (elevation: 12,276 ft; 3,742 m) is centered 50 km west and 2.8 km higher than foreground meadow (elevation: 2,950 ft.; 900 m); its eruptions began ~520 ka, its upper cone was built in late Pleistocene, and several eruptions have taken place in the Holocene. Signal Peak (elevation: 5,100 ft; 1,555 m), 20 km west of camera, is one of largest and highest eruptive centers in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field; short-lived shield, built around 3.7 Ma, is seven times older than Mount Adams. 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introductory Overview for Non-Geologists ...............................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Physiography, Environment, Boundary Surveys, and Access ......................................................6 Previous Geologic -

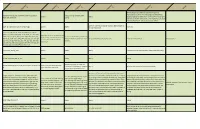

Uestion 1 Question 2 Question 3 Question 4 Question 5 Question 6

1 2 3 4 5 6 Notes Question Question Question Question Question Question We the people own federal land and have right and responsibility to use its resources using good stewardship. Randle to Pinto, Burley, Lone Tree, North Turk, Walupt, Hiking, hunting, firewood, berry [blank] [blank] Stopping logging has deprived us of resources and funding to Ryan Lake, Davis Mtn. picking maintain our forests. Meanwhile, we're expected to pay more taxes for less services. We can and must do better. 2324- off road motorcycle; 28- between 2809 and 292 for 2324- off road motorcycle on Juniper Ridge [blank] [blank] thank you off road motorcycle Area around Trout Lake to Mt Adams & Goose Lake to Willard. 88, 8871, 8854, 8851, 8810, 8860, 23, 2360, 8841, 98% of the above road which I travel 2480, 8831, 60, 6020, 6035, 6030, 6040, 8620, 6621, 66, Yes I use many for hiking and hunting need grading and other maint. Cave 66110, 86, 3200, 1831, 1840, 044, 030, 095, 531, 152, 061, and don't know or could never find no road should be converted to trails. [refer to attached letter] Attached letter Creek road is washed out above 120, 071, 24, 021, 420, 431, 020, 580, 210, 051, 040, 030, numbers. Cave Creek. 090, 141, 020, 080, 130, 011, 110, 060, 040, 070, 031, 507, 86, 0311, 011, 071, 080, 141 to name a few. 26- hunting, mining, 2612. [blank] [blank] [blank] Increase economic opportunities-> timber sales and mining 55, 78, 2304, 7605, 77, 29, 28 [blank] [blank] [blank] [blank] Reopen clags [sp?] no I roads for Gumble Packwood [????] south to Lewis River Southwest to Davis Creek road slided forwards recreation and small fires > products [blank] Pleas consider access for small forest products I5 slope slides from top [????] do [???] close roads with a p??? I'm not sure if "closure" or "decommission" is the correct Tongue Mountain- I believe I take the 2801 road which term here. -

Cowlitz Indian Tribe YOOYOOLAH!

Cowlitz Indian Tribe Cowlitz Indian Tribe S p r I n g 2 0 1 2 N e w s l e t t e r S p r I n g 2 0 1 2 N e w s l e t t e r YOOYOOLAH!YOOYOOLAH! YOOYOOLAH!YOOYOOLAH! THE CHAIRMAN’S CORNER THE CHAIRMAN’S CORNER It took the U.S. government decades to acknowledge the Cowlitz people It took the U.S. government decades to acknowledge the Cowlitz people as an Indian Tribe. Recognition brought the Cowlitz Tribe minimal fed- as an Indian Tribe. Recognition brought the Cowlitz Tribe minimal fed- eral dollars to operate a sovereign tribal government and offer a range of eral dollars to operate a sovereign tribal government and offer a range of social, housing, and cultural services and to receive health care from the social, housing, and cultural services and to receive health care from the Indian Health Services. Our leaders have accomplished a lot with those Indian Health Services. Our leaders have accomplished a lot with those funds already. funds already. With the announcement in 2002 of our recognition, Chairman John Barnett said, "After all these With the announcement in 2002 of our recognition, Chairman John Barnett said, "After all these years, justice has finally been done. We're not extinct. They are finally recognizing that we've al- years, justice has finally been done. We're not extinct. They are finally recognizing that we've al- ways been here and have always been a historic tribe." After the unsuccessful appeal by the ways been here and have always been a historic tribe." After the unsuccessful appeal by the Quinault Indian Nation, the Interior Department affirmed the earlier decision that acknowl- Quinault Indian Nation, the Interior Department affirmed the earlier decision that acknowl- edged the Cowlitz as a tribe. -

State Parks and Recreation Commission

Table 1 Ten Year Capital Plan Project Listing Estimated Estimated Estimated Estimated Prior Reapprop. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. Major Function, Agency, Project Estimate Total Expenditures 2017-19 2017-19 2019-21 2021-23 2023-25 2025-27 State Parks and Recreation Commission 30000086 Twin Harbors State Park: Relocate Campground State Building Construction Account - State 26,482,000 496,000 1,310,000 12,338,000 12,338,000 30000100 Fort Flagler - WW1 Historic Facilities Preservation State Building Construction Account - State 7,639,000 430,000 3,386,000 3,823,000 30000109 Fort Casey - Lighthouse Historic Preservation State Building Construction Account - State 1,616,000 217,000 1,399,000 30000155 Fort Simcoe - Historic Officers Quarters Renovation State Building Construction Account - State 1,770,000 292,000 1,478,000 30000253 Iron Horse - John Wayne Trail - Repair Tunnels Trestles Culv Ph 3 State Building Construction Account - State 4,877,000 606,000 4,271,000 30000287 Fort Worden - Housing Areas Exterior Improvements State Building Construction Account - State 6,605,000 500,000 1,043,000 2,461,000 2,601,000 30000305 Sun Lakes State Park: Dry Falls Campground Renovation State Building Construction Account - State 402,000 52,000 350,000 30000328 Camp Wooten Dining Hall Replacement State Building Construction Account - State 2,563,000 326,000 2,237,000 Table 1 Ten Year Capital Plan Project Listing Estimated Estimated Estimated Estimated Prior Reapprop. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. New Approp. -

Cowlitz Carcieri Submission

______________________________________________________________________________ FEE-TO-TRUST APPLICATION AND RESERVATION PROCLAMATION REQUEST SUPPLEMENTAL SUBMISSION on CARCIERI’S “UNDER FEDERAL JURISDICTION” REQUIREMENT JUNE 18, 2009 ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THE HON. LARRY ECHO HAWK THE HON. HILARY TOMPKINS ASSISTANT SECRETARY – INDIAN AFFAIRS SOLICITOR 1849 C STREET NW, MS 4141-MIB 1849 C STREET NW, MS 6412-MIB WASHINGTON, DC 20240 WASHINGTON, DC 20240 ______________________________________________________________________________ The Hon. William B. Iyall, Chairman (360) 577-8140 V. Heather Sibbison, Patton Boggs LLP (202) 457-6148 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................1 PART I: FEDERAL JURISDICTION OVER INDIANS AND INDIAN TRIBES IS PLENARY AND CONTINUOUS AS A MATTER OF LAW ..........................................................................................2 A. THE CARCIERI DECISION .......................................................................................................2 1. Brief Summary of the Court’s Holding in Carcieri v. Salazar...............................2 2. The “Facts” Before the Carcieri Court Were Unique to the Narragansett Tribe....................................................................................................5 -

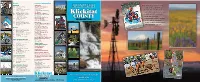

Layout 1 Copy 1

Events Contact Information Map and guide to points Festivals Goldendale From the lush, heavily forested April Earth Day Celebration – Chamber of Commerce of interest in and around Goldendale 903 East Broadway west side to the golden wheat May Fiddle Around the Stars Bluegrass 509 773-3400 W O Y L country in the east, Klickitat E L www.goldendalechamber.org L E Festival – Goldendale S F E G W N O June Spring Fest – White Salmon E L County offers a diverse selection Mt. Adams G R N O H E O July Trout Lake Festival of the Arts G J Chamber of Commerce Klickitat BICKLETON CAROUSEL July Community Days – Goldendale 1 Heritage Plaza, White Salmon STONEHENGE MEMORIAL of family activities and sight ~ Presby Quilt Show 509 493-3630 seeing opportunities. ~ Show & Shine Car Show www.mtadamschamber.com COUNTY July Nights in White Salmon City of Goldendale Wine-tasting, wildlife, outdoor Art & Fusion www.cityofgoldendale.com WASHINGTON Aug Maryhill Arts Festival sports, and breathtaking Sept Huckleberry Festival – Bingen Museums scenic beauty beckon visitors Dec I’m Dreaming of a White Salmon Carousel Museum–Bickleton Holiday Festival 509 896-2007 throughout the seasons. Y E L S Open May-Oct Thurs-Sun T E J O W W E G A SON R R Rodeos Gorge Heritage Museum D PETE O L N HAE E IC Y M L G May Goldendale High School Rodeo BLUEBIRDS IN BICKLETON 509 493-3228 HISTORIC RED HOUSE - GOLDENDALE June Aldercreek Pioneer Picnic and Open May-Sept Thurs-Sun Rodeo – Cleveland Maryhill Museum of Art June Ketcham Kalf Rodeo – Glenwood 509 773-3733 Aug Klickitat County Fair and Rodeo – Open Daily Mar 15-Nov 15 Goldendale www.maryhillmuseum.org Aug Cayuse Goldendale Jr. -

South Rainier Elk Herd

Washington State Elk Herd Plan SOUTH RAINIER ELK HERD Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Program 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA 98501-1091 Prepared by Min T. Huang Patrick J. Miller Frederick C. Dobler January 2002 Director, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Date January 2002 i Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife STATE OF WASHINGTON GARY LOCKE, GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE JEFF KOENINGS, PH. D., DIRECTOR WILDLIFE PROGRAM DAVE BRITTELL, ASSISTANT DIRECTOR GAME DIVISION DAVE WARE, MANAGER This Program Receives Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration funds. Project W-96-R-10, Category A, Project 1, Job 4 This report should be cited as: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2002. South Rainier Elk Herd Plan. Wildlife Program, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia. 32 pp. This program receives Federal financial assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. The U.S. Department of the Interior and its bureaus prohibit discrimination on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability and sex. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity or facility, please write to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of External Programs, 4040 N. Fairfax Drive, Suite 130, Arlington, VA 22203 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………….. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………. v INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………. 1 The Plan……………………………………………………………………………………. -

ELK ECOLOGY and MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES at MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK

ELK ECOLOGY and MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES at MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK William P. Bradley Chas. H. Driver National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit College of Forest Resources University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 ELK ECOLOGY and MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES at MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK William P. Bradley1 Chas. H. Driver2 National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit College of Forest Resources University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 CPSU/UW 81-2 Winter 1981 'formerly Research Associate, College of Forest Resources 2Professor, College of Forest Resources The research in this publication was supported by National Park Service contract CX-9000-6-0093. INTRODUCTION Elk management in the western states has often been subject to heated and emotional controversies, both among different public agencies responsible for elk management and between these agencies and the public at large. The National Park Service (NPS) is extremely susceptible to adverse criticism and negative public opinion resulting from elk management decisions, because they do not have at their disposal the accepted managerial tool of sport hunting to control and regulate problem populations. The NPS's direct reduction-by-shooting program in Yellowstone Park has become a classic example of a managerial solution resulting in inflammatory inter-agency conflict and public relations problems. (See Pengelly 1963 and Woolf 1971 for excellent discussions of the Yellowstone situation.) The intent of this paper is to summarize the elk management problems at Mount Rainier National Park in the State of Washington and the actions taken to mitigate them. The seat of this controversy revolves around a large summering elk population's impact on the sub-alpine meadow system con tained within the park. -

Geomorphic Assessment of Thirty Miles of Railroad Infrastructure Along the Klickitat River and Swale Creek, Klickitat County, WA Preliminary Report

Geomorphic Assessment of Thirty Miles of Railroad Infrastructure along the Klickitat River and Swale Creek, Klickitat County, WA Preliminary Report Prepared by: Will Conley, Hydrologist/Geomorphologist Yakama Nation Fisheries Program Klickitat Field Office Wahkiacus, WA Prepared for: United States Department of Energy Washington State Recreation and Bonneville Power Administration Conservation Office Environment, Fish, and Wildlife Program Salmon Recovery Funding Board Portland, Oregon Olympia, WA Project Number: 1997-056-00 Project Number: 10-1741 May 31, 2015 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Project funding was provided by Bonneville Power Administration project number 1997-056-00 (Klickitat Watershed Enhancement Project) and Salmon Recovery Funding Board project number 10-1741. David Lindley (Habitat Biologist, YNFP) provided valuable assistance inventorying crossing structures and reviewing report drafts. The success of the field-based portion of this study was greatly assisted by coordination with Andrew Kallinen, Ranger, Columbia Hills State Park Complex. 3 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 7 Study Area and Geographic Scope ............................................................................................. 8 Fisheries Significance ................................................................................................................. 9 Study Purpose .......................................................................................................................... -

Lewis River Hydroelectric Project Relicensing

United StatesDepartment of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Western Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 DesmondDr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey,Washington 98503 In ReplyRefer To: SCANNED 1-3-06-F-0177 sEPI 5 2006 MagalieR. Salas,Secretary F6deralEnergy Regulatory Commission 888First Sffeet,NE WashingtonD.C. 24426 Attention:Ann Ariel Vecchio DearSecretary Salas: This documenttransmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's(Service) Biological Opinion on the effectsto bull trout(Salvelinus confluentus),northern spotted owls (Srrlxoccidentalis caurina)and bald eagles(Haliaeetus leucocephalus) fromthe relicensingof the Lewis River HydroeiectricProjects: Merwin (FERC No. 935),Yale (FERC No. 2071),Swift No. 1 (FERC No. Zr 11),and swift No. 2 (FERCNo. 2213). Theaction that comprises this consultationunder theEndangered Species Act of 1973,as amended (16 U.S.C. l53I et seq.)is therelicensing of the Lewis-RiverHydroelectric Projects by the FederalEnergy Regulatory Commission and the interdependentactions contained in the SettlementAgreement (PacifiCorp et aL.2004e),dated November30,2004,and Washington Department of Ecology's401 Certifications. Consultationfor the relicensingof the Lewis River Plojectswas initiated by the Commission's letterto the Servicewhich was received in our officeon October11,2005. Based on our letter datedMarch15,2006,the deadline for completingthis consultationwas extended by mutual agreementuntil May 5, 2006. On June12,2006,with concurrenceby thelicensees,we submittedanother request for an extensionto SeptemberI,2006, to -

View Or Download the Print

AppalachianThe June / July 2012 VOICE THIS IS OUR LAND The Plight of Our Public Places and the Compelling Case for Conservation Hidden ALSO INSIDE: Coal’s Big Decline • Return of the American Chestnut Treasures Special Insert The Appalachian Voice cross Appalachia A publication of A Environmental News From Around the Region AppalachianVoices A Note from our Executive Director 171 Grand Blvd • Boone, NC 28607 It’s no secret that kids are now spend- 828-262-1500 Since the days of the uncompromising Republican “Kids In Parks” Gets Kids Outside ing more time indoors. A Kaiser Fam- www.AppalachianVoices.org president, Theodore Roosevelt, the struggle to protect our [email protected] ily Foundation study published in 2010 vital resources has often been countered by a nearly limit- By Jessica Kennedy At the core of Kids In Parks is its Trails Ridges and Active Caring Kids, showed that children ages 8 to 18 spend EDITOR ....................................................... Jamie Goodman less greed for financial gain. But as the venerable Roosevelt There is a growing distance be- MANAGING EDITOR ........................................... Brian Sewell or TRACK, program. The Kids In an average of 7 hours and 38 minutes us- — who greatly expanded the budding U.S. national park tween children and nature, says Jason ASSOCIATE EDITOR ............................................Molly Moore Parks website provides links to maps ing entertainment media in a typical day. and national forest systems — said in his 1907 message to Urroz, director of Kids In Parks, an DISTRIBUTION MANAGER .................................. Maeve Gould and brochures for each of the 10 par- Kids In Parks is working to change GRAPHIC DESIGNER .........................................Meghan Darst Congress, “We are prone to speak of the resources of this innovative program working to get “There can be ticipating trails.