Negative Markers in East Cree and M Ontagnais

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

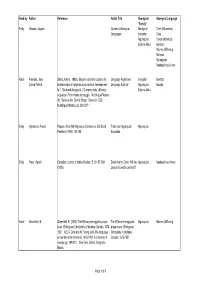

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

Master of Arts

SOUI\D CHAI\IGE IN OtD MOI\ITAGITAIS by Christopher W. Haryey A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies ln Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS I)epartment of Linguistics Ilniversity of Manitoba \ffinnipeg, Manitoba @ Christopher'W. Harve¡ 2005 THE UNTVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ?t*itJrrt COPYRIGHT PERMISSION SOUND CIIANGE IN OLD MONITAGNAIS BY Christopher W. Harvey A ThesislPracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree Master Of Arts Christopher W. Harvey O 2005 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. SOUND CHANGE IN OLD MONTAGNAIS Chris Harvey ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the sound changes which occurred from reconstructed Proto- Algonquian to Old Montagnais. The Old Montagnais language was recorded by the Jesuits during the seventeenth century in the region of Québec City, Lac Saint-Jean and the lower Saguenay River at the Tadoussac mission. Their most important works which survive to this day are two dictionaries, Díctionnaire montagnais by Antoine Silvy and Racines montagnøises by Bonaventure Fabvre. -

Of the University of Manitoba in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Àrts

PHONOTOGICÀt VÀRIÀNTS I PUKATÀI^IÀGÀN WOODS CREE by Jennifer M. Greensmith A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studíes of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfiLlment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Àrts Winnipeg, Maniloba 1 985 (e) Jennifer M. Greensmith, 1985 PHONOLOGICAL VARIANTS IN PUKATAI.IAGAN I^IOODS CREE BY JENNIFER I"f . GREENSMITH A thesis subntitted to the Faculty of Craduate Studies of the Ulriversity of Ma¡ritoba in partial fulfill¡nent of the requirenrents of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS o teg6 Pernrission has bee¡r granted to the LIBRARY OF THE UNIVER- SITY OF MAN¡TOBA to lend or sell copies of this thesis. to the NATIOTT-AL LIBRARY OF CANADA ro microfilnr this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and UNIVERSITY lvf ICROFILIvf S to publish an abstract of this thesis. Thc' author reserves other publicatiort rights, alld neithe r tire tlesis nor extensive extracts fronl it may be ¡lrinted o¡ othc'r- wise reproduced without the author's writte¡l pernrissiorr. 111 PREFACE This thesis is a first attempt at a study of the phonological contrasts and surface variants of Woods Cree, based on the dialect spoken at Pukalawagan, Manitoba. The analysis is based on direct elicitation and on narrative texts, one of whieh is included as an appendi x . Few studies of Cree phonology exist, and no phonological st.udy has been made of the Woods dialect. Traditionally, Woods Cree has been identified as t.hat dialect of Cree which has the p-reflex of Proto Àlgonquian *1. -

Aboriginal Languages in Canada

Catalogue no. 98-314-X2011003 Census in Brief Aboriginal languages in Canada Language, 2011 Census of Population Aboriginal languages in Canada Census in Brief No. 3 Over 60 Aboriginal languages reported in 2011 The 2011 Census of Population recorded over 60 Aboriginal languages grouped into 12 distinct language families – an indication of the diversity of Aboriginal languages in Canada.1 According to the 2011 Census, almost 213,500 people reported an Aboriginal mother tongue and nearly 213,400 people reported speaking an Aboriginal language most often or regularly at home.2,3 Largest Aboriginal language family is Algonquian The Aboriginal language family with the largest number of people was Algonquian. A total of 144,015 people reported a mother tongue belonging to this language family (Table 1). The Algonquian languages most often reported in 2011 as mother tongues were the Cree languages4 (83,475), Ojibway (19,275), Innu/Montagnais (10,965) and Oji-Cree (10,180). People reporting a mother tongue belonging to the Algonquian language family lived across Canada. For example, people with the Cree languages as their mother tongue lived mainly in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alberta or Quebec. Those with Ojibway or Oji-Cree mother tongues were mainly located in Ontario or Manitoba, while those whose mother tongue was Innu/Montagnais or Atikamekw (5,915) lived mostly in Quebec. Also included in the Algonquian language family were people who reported Mi'kmaq (8,030) who lived mainly in Nova Scotia or New Brunswick, and those who reported Blackfoot (3,250) as their mother tongue and who primarily lived in Alberta. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

Download (7MB)

- "SMALL" TALK: THE FORM AND FUNCTION OF THE DIMINUTIVE SUFFIX IN NORTHERN EAST CREE by © Amanda Cunningham A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland May 11, 2008 St. John's Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract Diminutivization is a morphological process that is commonly attested among the world's languages. Though it has been studied in numerous languages belonging to a variety of language families, there has been a limited amount of research conducted on the diminutive in Algonquian. This thesis examines the diminutive suffix in Northern East Cree (NEC), a subdialect of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi which is a Central Algonquian language spoken in Quebec. Comparisons, where possible, are made with other Algonquian dialects for which there is diminutive data. The phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic properties of the particle, nominal, and verbal diminutive in NEC are described. There is a particular focus on the verbal diminutive, the investigation of which analyzes its distribution by identifying what elements of the sentence (subject, object, and/or verb) it modifies within each of the four Algonquian verb classes. The extent to which the Algonquian diminutive behaves like inflectional morphology is also discussed. 11 Acknowledgments Completion of a project of this magnitude can never be achieved by just one individual. I owe my success to a number of people and organizations. First, and foremost, I must acknowledge the amazing team of faculty, administrative staff, and graduate students that comprise the Linguistics Department at MUN. -

Building a Community Language Development Team with Québec Naskapi Bill Jancewicz, Marguerite Mackenzie, George Guanish, Silas Nabinicaboo

Building a Community Language Development Team with Québec Naskapi Bill Jancewicz, Marguerite MacKenzie, George Guanish, Silas Nabinicaboo Although the Naskapi language has many features in common with other Algonquian languages spoken in northern Quebec, it is in a unique situation because of the Naskapi people’s relatively late date of European contact, their geographic isolation, and the fact that, within their territory, Naskapi speakers outnumber speakers of Canada’s official languages. Historically, the vernacular word from which we derive the modern term “Naskapi” was applied to people not yet influenced by European culture. Nowadays, however, it refers specifically to the most remote Indian groups of the Quebec-Labrador peninsula (Mailhot, 1986). The Naskapi of today, who now comprise the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach near Schefferville, are direct descendants of nomadic caribou hunters of the Ungava tundra region. Although they are sometimes considered a part of the larger Innu grouping (also referred to as Montagnais-Naskapi by linguists and anthropologists), the Naskapi themselves insist that they are a unique people-group. Indeed, it can be shown both linguistically and ethnographically that the Naskapi are distinct from their neighbours (Jancewicz, 1998). Although they do share many cultural and linguistic traits with the Labrador Innu, the Quebec Montagnais, and the East Cree, they also have a unique history and some distinct linguistic forms that set them apart. The Naskapi language has retained a core vocabulary not found in related languages or in neighbouring dialects, although the majority of the vocabulary and the pronunciation reflect the variety of their contacts with other language groups. -

Supplementary Resources 2 Connect

March 2015/Mars 2015 SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES 2 CONNECT • "Apihawikosisan" Law, Language, Life: A Plains Cree Speaking Metis Woman in Montreal apihtawikosisan.com This blog follows the life of a Metis teacher and has information on how to attend her "language nest" style Plains Cree language course in Montreal. The site also lists a wide variety of links to Cree language and cultural resources. • Cree Cultural Institute http://creeculture.ca/ This site is an excellent destination for learning about the culture and language of Crees living in the James Bay and Hudson Bay regions of Quebec. Among the many features of this website are an archive of historical photographs, an online exhibition of Cree artifacts from the region, and translated traditional stories. • Centre for Race and Culture http://www.cfrac.com/ This organization based in Edmonton, AB organizes programs and projects to help minority, immigrant, and refugee communities. One of these projects is on-site Cree language lessons. • The Nehiyawewin (Cree) Word/Phrase of the Day https://www.facebook.com/groups/18414147673/ This Facebook group brings together users from across the world to share their favourite Cree words and phrases as a way to promote and strengthen the language and the people it represents. 3 LEARN • A-mowin Virtual Language Classroom http://learncreeonline.blogspot.ca This blog offers free online Cree language lessons every Thursday at 9 pm EST. • Alberta Language Technology Lab http://altlab.artsrn.ualberta.ca/?page_id=150 This team at the University of Alberta has created a number of Plains Cree language tools including a Cree/English dictionary and linguistic generation tools. -

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh

Unicode Cree Syllabics for Windows and Macintosh 37th Algonquian Conference, Ottawa 2005 Bill Jancewicz SIL International and Naskapi Development Corporation ABSTRACT Submitted as an update to a presentation made at the 34th Algonquian Conference (Kingston). The ongoing development of the operating systems has included increased support for cross-platform use of Unicode syllabic script. Key improvements that were included in Macintosh's OS X.3 (Panther) operating system now allow direct keyboarding of Unicode characters by means of a user-defined input method. A summary and comparison of the available tools for handling Unicode on both Windows and Macintosh will be discussed. INTRODUCTION Since 1988 the author has been working in the Naskapi language at Kawawachikamach with the primary purpose of linguistic analysis and Bible translation, sponsored by Wycliffe Bible Translators and SIL International. Related work includes mother tongue translator training, Naskapi literature and curriculum development. Along with the language work the author also developed methods of production for Naskapi language materials in syllabic script by means of the computer. With the advent of high quality publishing capabilities in newer computers, procedures were updated to keep pace with the improving technology. With resources available from SIL International computer services department, a very satisfactory system of keyboarding syllabic texts in Naskapi was developed. At the urging of colleagues working in related languages, the system was expanded to include the wider inventory of standard Eastern and Western Cree syllabics. While this has pushed the limit of what is possible with the current technology, Unicode makes this practical. Note that the system originally developed for keyboarding Naskapi syllabics is similar but not identical to the Cree system, because of the unique local orthography in use at Kawawachikamach. -

MOT Proceedings Paper-Current

Allophony and Contrast without Features: * Laryngeal Development in Early Grammars Heather Goad McGill University SUMMARY This paper examines the development of laryngeal allophony and contrast in Amahl’s grammar of English (Smith 1973). It is shown that, before contrast has been established, laryngeal allophones display unexpected distributions: marked allophones appear in ‘weak’ positions, whether defined in prosodic, articulatory or perceptual terms; unmarked allophones appear in ‘strong’ positions. Further, when laryngeal contrasts begin to emerge, they initially develop in non-optimal positions. The solution proposed lies in the formal expression of allophony and contrast: certain phonological relations among segments arise without the features seemingly involved being employed by the grammar; allophony and early contrast are expressed solely in structural terms. Once laryngeal features are projected, at later stages in development, a less surprising pattern of behaviour emerges, one that is more consistent with perceptual and articulatory considerations on optimal positions for contrast. RÉSUMÉ Cet article considère le développement des allophones et contrastes laryngiens dans la grammaire d’Amahl, un enfant anglophone (Smith 1973). On montre que, avant que les contrastes soient établis, les allophones laryngiens observent des distributions inattendues : les allophones marqués se trouvent dans les positions «faibles» si les positions sont déterminées en termes prosodiques, articulatoires ou perceptuels ; les allophones non-marqués se trouvent dans les positions «fortes». De plus, quand les contrastes laryngiens commencent à apparaître, initialement ils se développent dans les positions non- optimales. On propose que la solution à ce problème se trouve dans l’expression formelle d’allophonie et de contraste : certaines relations phonologiques entre les segments émergent sans les traits qui semblent être utilisés par la grammaire ; l’allophonie et les premiers contrastes sont exprimés uniquement en termes structurels.