Strategic Plan for Revitalizing the Hul'qumi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

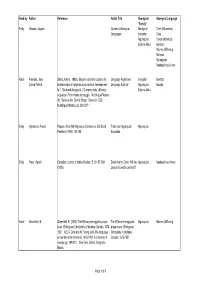

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Part-Time Instructor Dakelh (Carrier)

Part-Time Instructor Posting #FAPT01-21 Dakelh (Carrier) Language Instructor First Nations Studies Faculty of Indigenous Studies, Social Sciences and Humanities The University of Northern British Columbia invites applications for an instructor in the Department of First Nations Studies to teach a single introductory Dakelh (Carrier) Language Course during the 2021 Spring Semester. This course will be taught online and is scheduled to run from 31 May 2021 to 18 June 2021 from 9:00 am to 11:50 am with an exam to be scheduled between 21-25 June 2021. Interested applicants must be willing to teach online, have experience teaching in a post-secondary and/or adult education setting, and possess a working knowledge of Dakelh. About the University and its Community Located in the spectacular landscape of northern British Columbia, UNBC is one of Canada’s best small research-intensive universities, with a core campus in Prince George and three regional campuses in Northern BC (Quesnel, Fort St. John and Terrace). We have a passion for teaching, discovery, people, the environment, and the North. Our region is comprised of friendly communities, offering a wide range of outdoor activities including exceptional skiing, canoeing and kayaking, fly fishing, hiking, and mountain biking. The lakes, forests and mountains of northern and central British Columbia offer an unparalleled natural environment in which to live and work. To Apply Applicants should forward their cover letter and curriculum vitae to the Chair of First Nations Studies, Dr. Daniel Sims, at [email protected] by 30 April 2021. All qualified candidates are encouraged to apply; however, Canadians and permanent residents will be given priority. -

Language Data Tables User Guide

Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous Communities in Canada Language Data Tables User Guide Version 0.7.1 Norris Research Inc. https://norrisresearch.com/ref_tables.htm 1 January 2021 Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Recommended Citation: Norris Research Inc. (2020). Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous communities in Canada: Language Data Tables Users Guide, 01 January 2021. Draft Report prepared under contract with the Department of Canadian Heritage. Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 !! IMPORTANT !! ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Cautionary Note ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 Website Tips and Tricks ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tree View ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

An Anatomy of Carrier Cremation Cruelty in the Historical Record1

“Caledonian Suttee”? An Anatomy of Carrier Cremation 1 Cruelty in the Historical Record I.S. MACL AREN etween 1820 and 1860 four published stories about Native barbarity contributed to the demonization of the inhabitants of the Pacific Slope inland from coastal areas. The first was B 1812 the record of a Carrier cremation in January at Stuart Lake; the second was an incident of Iroquois cannibalism in May 1817 on the upper Columbia River; the third was the murder by a vengeful Shuswap of Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor Samuel Black at Thompson River Fort on 8 February 1841; and the fourth was the massacre by Caiuse of the Whitmans at Waillatpu in November 1847.2 These stories came to form readers’ perceptions of the barbarians of the Interior, and became instances of what has been called occupational folklore.3 Of these, Carrier cremation cruelty alone involved only Native people. It was “the subject of much jaundiced comment by Europeans,” whose 1 An earlier version of this essay was read before the British Columbia Inside/Out Conference organized by BC Studies and the BC Political Studies Association, University of Northern British Columbia, 28-30 April 2005. I wish to thank Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy for generously permitting me access to their extensive library, which brought to my attention many sources cited herein. 2 The first published appearances of each of the four occurred in Daniel Williams Harmon, A Journal of Voyages and Travels in the Interiour of North America, ed. Rev. Daniel Haskel (Andover, VT: Flagg and Gould, 1820), 215-18; Ross Cox, Adventures on the Columbia River, 2 vols. -

Lhtako Dene First Nation

northern health the northern way of caring ABORIGINAL RESOURCE GUIDE 2019 Artwork on cover by Artist Curtis Boyd northern health TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 4 Ndazkoh First Nation ......................................... 6 Dene First Nation............................................. 10 ?Esdilagh First Nation ..................................... 14 Lhoosk’uz Dene First Nation ........................... 18 Additional Resources ....................................... 21 Medicine Wheel ............................................... 29 Quesnel Health Services Contact Numbers ..... 31 Southern Carrier Terminology ......................... 32 Hospital Terminology ...................................... 34 Footprints in Stone.......................................... 37 Contacts .......................................................... 48 ABORIGINAL 2 RESOURCE GUIDE 3 northern health INTRODUCTION Quesnel Health Services provides services to four local bands: Ndazkoh First Nations (Nazko), Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation (Kluskus), ?Esdilagh First Nation (Alexandria) and Lhtako Dene Nation (Red Bluff), as well as to the urban population of local First Nation, Inuit and Metis people. This Guide will provide information on our local First Nations, community resources, culture and history. A Quick Overview Nazko, Kluskus and Red Bluff are all Southern Carrier Nations. Their traditional language is Carrier, which is part of the northern Athabaskan language family which is spoken throughout Northern -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Language Revitalization on the Web: Technologies and Ideologies Among the Northern Arapaho

LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION ON THE WEB: TECHNOLOGIES AND IDEOLOGIES AMONG THE NORTHERN ARAPAHO by IRINA A. VAGNER B.A., Univerisity of Colorado, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Linguistics 2014 This thesis entitled: Language Revitalization on the Web: Technologies and Ideologies among the Northern Arapaho written by Irina A. Vagner has been approved for the Department of Linguistics ___________________________________ (Dr. Andrew Cowell) ___________________________________ (Dr. Kira Hall) _________________________________ (Dr. David Rood) Date: April 16, 2014 The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 130411 Abstract Vagner, Irina A. (MA, Linguistics) Language Revitalization on the Web: Technologies and Ideologies among the Northern Arapaho Thesis directed by Professor Andrew J. Cowell With the advances in web technologies, production and distribution of the language learning resources for language revitalization have become easy, inexpensive and widely accessible. However, not all of the web-based language learning resources stimulate language revitalization. This thesis explores the language ideologies used and produced by the Algonquian language learning resources to determine the most successful way to further develop online resources for the revitalization of the Arapaho language with the Arapaho Language Project. The data was collected on Algonquian language learning websites as well as during field research on the Wind River Indian Reservation; this field research included observing Arapaho language classrooms and conducting a usability survey of the Arapaho Language Project. -

Applying Universal Dependency to the Arapaho Language

Applying Universal Dependency to the Arapaho Language Irina Wagner1, Andrew Cowell1, Jena D. Hwang2 1University of Colorado Boulder, Department of Linguistics; 2IHMC irina.wagner, james.cowell @colorado.edu, [email protected] { } Abstract Applying the UD rules while annotating the data from the Arapaho (Algonquian) language, several This paper discusses the use of Universal specific features were observed to fall outside of Dependency for annotations of a Native the charted labels. Since the language does not North American language Arapaho (Algo- have a fixed word order and allows discontinuous nquian). While some relations of the uni- constituency, dependencies on the previous word versal dependency perfectly correspond were avoided and re-analyzed. The most problem- with those in Arapaho, language specific atic dependency distinction in this language is the annotations of verbal arguments elucidate variation in relations between a verb and its argu- problems of assuming certain syntactic ments. This paper examines the correlation of the categories across languages. By critiquing dependency relations in the UD scheme and their the influence of grammatical structures of practical application for the Arapaho data. Us- major European and Asian languages in ing the UD framework, we create guidelines for establishing the UD framework, this paper annotating this data. In considerations of space, develops guidelines for annotating a poly- this paper primarily focuses on the argument struc- synthetic agglutinating language and sets tures defined by the UD and their correspondences a path to developing a more comprehen- to the Arapaho syntactic patterns. An additional sive cross-linguistic approach to syntactic discussion of non-verbal roots and topicality prob- annotations of language data. -

Taking the Laboratory Into the Field

arli1Whalen ARI 25 August 2014 21:38 Taking the Laboratory into the Field D.H. Whalen1,2 and Joyce McDonough3 1Program in Speech–Language–Hearing Sciences, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016; email: [email protected] 2Haskins Laboratories, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 3Department of Linguistics, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York 14627 Annu. Rev. Linguist. 2015. 1:14.1–14.21 Keywords The Annual Review of Linguistics is online at phonetics, morphology, syntax, semantics, experiments, language linguistics.annualreviews.org documentation This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-124915 Abstract Copyright © 2015 by Annual Reviews. We review the development of methodologies and technologies of All rights reserved empirical linguistic work done outside traditional academic labora- tories. The integration of such results with contemporary language documentation and linguistic theory is an increasingly important component of language analysis. Taking linguistic inquiry out of the lab and away from well-described and familiar data brings challenges in logistics, ethics, and the definition of variability within language use. In an era when rapidly developing technologies offer new poten- tial for collecting linguistic data, the role of empirical or experimental work in theoretical discussions continues to increase. Collecting linguistic data on understudied languages raises issues about its aim vis-à-vis the academy and the language communities, and about its integration into linguistic theory. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 035 RC 023 244 AUTHOR Dayo, Dixie Masak, Ed. TITLE Sharing Our Pathways: A Newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative, 2001. INSTITUTION Alaska Federation of Natives, Anchorage.; Alaska Univ., Fairbanks. Alaska Native Knowledge Network. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA. Division of Educational System Reform.; Rural School and Community Trust, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 86p.; For volume 5, see ED 453 984. AVAILABLE FROM Alaska Native Knowledge Network/Alaska RSI, University of Alaska Fairbanks, P.O. Box 756730, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6730. Tel: 907-474-5086. For full text: http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/sop. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Sharing Our Pathways; v6 n1-5 2001 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; American Indian Culture; *American Indian Education; American Indian Languages; Bilingual Education; Conferences; Cultural Maintenance; *Culturally Relevant Education; *Educational Change; Elementary Secondary Education; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Language Maintenance; Outdoor Education; Rural Education; School Community Relationship; Science Education; Teacher Education IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Arctic; Eskimo Culture; *Indigenous Knowledge Systems ABSTRACT This document contains the five issues of "Sharing Our Pathways" published in 2001. This newsletter of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative (AKRSI) documents efforts to make Alaska rural education--particularly science education--more culturally relevant to Alaska Native students.