The Linguistic Division in India: a Latent Conflict?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Language Use in Nepal

CHAPTER 2 LANGUAGE USE IN NEPAL Yogendra P. Yadava* Abstract This chapter aims to analyse the use of languages as mother tongues and second lan- guages in Nepal on the basis of data from the 2011 census, using tables, maps, and figures and providing explanations for certain facts following sociolinguistic insights. The findings of this chapter are presented in five sections. Section 1 shows the impor- tance of language enumeration in censuses and also Nepal’s linguistic diversity due to historical and typological reasons. Section 2 shows that the number of mother tongues have increased considerably from 92 (Census 2001) to 123 in the census of 2011 due to democratic movements and ensuing linguistic awareness among Nepalese people since 1990. These mother tongues (except Kusunda) belong to four language families: Indo- European, Sino-Tibetan, Austro-Asiatic and Dravidian, while Kusunda is a language isolate. They have been categorised into two main groups: major and minor. The major group consists of 19 mother tongues spoken by almost 96 % of the total population, while the minor group is made up of the remaining 104 plus languages spoken by about 4% of Nepal’s total population. Nepali, highly concentrated in the Hills, but unevenly distributed in other parts of the country, accounts for the largest number of speakers (44.64%). Several cross-border, foreign and recently migrated languages have also been reported in Nepal. Section 3 briefly deals with the factors (such as sex, rural/ urban areas, ethnicity, age, literacy etc.) that interact with language. Section 4 shows that according to the census of 2011, the majority of Nepal’s population (59%) speak only one language while the remaining 41% speak at least a second language. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Linguistic Survey of India Bihar

LINGUISTIC SURVEY OF INDIA BIHAR 2020 LANGUAGE DIVISION OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA i CONTENTS Pages Foreword iii-iv Preface v-vii Acknowledgements viii List of Abbreviations ix-xi List of Phonetic Symbols xii-xiii List of Maps xiv Introduction R. Nakkeerar 1-61 Languages Hindi S.P. Ahirwal 62-143 Maithili S. Boopathy & 144-222 Sibasis Mukherjee Urdu S.S. Bhattacharya 223-292 Mother Tongues Bhojpuri J. Rajathi & 293-407 P. Perumalsamy Kurmali Thar Tapati Ghosh 408-476 Magadhi/ Magahi Balaram Prasad & 477-575 Sibasis Mukherjee Surjapuri S.P. Srivastava & 576-649 P. Perumalsamy Comparative Lexicon of 3 Languages & 650-674 4 Mother Tongues ii FOREWORD Since Linguistic Survey of India was published in 1930, a lot of changes have taken place with respect to the language situation in India. Though individual language wise surveys have been done in large number, however state wise survey of languages of India has not taken place. The main reason is that such a survey project requires large manpower and financial support. Linguistic Survey of India opens up new avenues for language studies and adds successfully to the linguistic profile of the state. In view of its relevance in academic life, the Office of the Registrar General, India, Language Division, has taken up the Linguistic Survey of India as an ongoing project of Government of India. It gives me immense pleasure in presenting LSI- Bihar volume. The present volume devoted to the state of Bihar has the description of three languages namely Hindi, Maithili, Urdu along with four Mother Tongues namely Bhojpuri, Kurmali Thar, Magadhi/ Magahi, Surjapuri. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Manual of Instructions for Editing, Coding and Record Management of Individual Slips

For offiCial use only CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 MANUAL OF INSTRUCTIONS FOR EDITING, CODING AND RECORD MANAGEMENT OF INDIVIDUAL SLIPS PART-I MASTER COPY-I OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL&. CENSUS COMMISSIONER. INOI.A MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS Pages GENERAlINSTRUCnONS 1-2 1. Abbreviations used for urban units 3 2. Record Management instructions for Individual Slips 4-5 3. Need for location code for computer processing scheme 6-12 4. Manual edit of Individual Slip 13-20 5. Code structure of Individual Slip 21-34 Appendix-A Code list of States/Union Territories 8a Districts 35-41 Appendix-I-Alphabetical list of languages 43-64 Appendix-II-Code list of religions 66-70 Appendix-Ill-Code list of Schedules Castes/Scheduled Tribes 71 Appendix-IV-Code list of foreign countries 73-75 Appendix-V-Proforma for list of unclassified languages 77 Appendix-VI-Proforma for list of unclassified religions 78 Appendix-VII-Educational levels and their tentative equivalents. 79-94 Appendix-VIII-Proforma for Central Record Register 95 Appendix-IX-Profor.ma for Inventory 96 Appendix-X-Specimen of Individual SHp 97-98 Appendix-XI-Statement showing number of Diatricts/Tehsils/Towns/Cities/ 99 U.AB.lC.D. Blocks in each State/U.T. GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS This manual contains instructions for editing, coding and record management of Individual Slips upto the stage of entry of these documents In the Direct Data Entry System. For the sake of convenient handling of this manual, it has been divided into two parts. Part·1 contains Management Instructions for handling records, brief description of thf' process adopted for assigning location code, the code structure which explains the details of codes which are to be assigned for various entries in the Individual Slip and the edit instructions. -

THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2015 By

AS INTRODUCED IN LOK SABHA Bill No. 90 of 2015 THE CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2015 By SHRI ASHWINI KUMAR CHOUBEY, M.P. A BILL further to amend the Constitution of India. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Sixty-sixth Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. This Act may be called the Constitution (Amendment) Act, 2015. Short title. 2. In the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution,— Amendment of the Eighth (i) existing entries 1 and 2 shall be renumbered as entries 2 and 3, respectively, Schedule. 5 and before entry 2 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— "1. Angika."; (ii) after entry 3 as so renumbered, the following entry shall be inserted, namely:— "4. Bhojpuri."; and (iii) entries 3 to 22 shall be renumbered as entries 5 to 24, respectively. STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS Language is not only a medium of communication but also a sign of respect. Language also reflects on the history, culture, people, system of governance, ecology, politics, etc. 'Bhojpuri' language is also known as Bhozpuri, Bihari, Deswali and Khotla and is a member of the Bihari group of the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European language family and is closely related to Magahi and Maithili languages. Bhojpuri language is spoken in many parts of north-central and eastern regions of this country. It is particularly spoken in the western part of the State of Bihar, north-western part of Jharkhand state and the Purvanchal region of Uttar Pradesh State. Bhojpuri language is spoken by over forty million people in the country. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

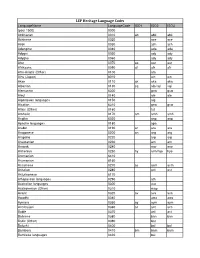

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang