Willows Management Guide Current Management and Control Options for Willows (Salix Spp.) in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Weeping Willow Salix Babylonica

Weeping willow Salix babylonica Description Introduced to North America as an ornamental. Habit Perennial tree to 40 ft tall; rounded crown; long, hanging branches; grayish-brown, irregularly furrowed bark. Leaves Alternate, simple, very narrowly lance-shaped, finely serrated margin, yellow-green above and milky green below, 3-6 inches in length, 3/8 to 1/2 inch in width. Stems Very slender; smooth; olive-green to pale yellowish brown; hanging or drooping for long distances; almost rope-like; buds are small, appressed and covered by a single, cap-like Source: MISIN. 2021. Midwest Invasive Species Information Network. Michigan State University - Applied Spatial Ecology and Technical Services Laboratory. Available online at https://www.misin.msu.edu/facts/detail.php?id=148. scale; terminal buds lacking. Flowers Dioecious, males and females appear as upright catkins and are quite fuzzy, 1 inch long, appearing before or with the leaves. Fruits and Seeds A 1 in long cluster of valve-like capsules, light brown in color, contains many fine, cottony seeds; ripen in late May to early June. Habitat Native to Asia. Reproduction By herbaceous stem cuttings, woody stem cuttings or softwood cuttings. Similar White Willow (Salix alba); Black Willow (Salix nigra); Corkscrew Willow (Salix matsudana Koidzumi ). Monitoring and Rapid Response Hand pull small seedlings; use machinery to remove larger trees and root systems in dry areas; effectively controlled using any of several readily available general use herbicides such as glyphosate. Credits The information provided in this factsheet was gathered from the USDA PLANTS Database and Virginia Tech Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation VTree. -

Cultivated Willows Would Not Be Appropriate Without Mention of the ‘WEEPING WILLOW’

Alexander Robertson Notes on willows cultivated in Scotland and a few sketches of willows sampled from my clonal collection HISTORICAL NOTES Since the knowledge of willows is of great antiquity, it is with the ancient Greeks and Romans we shall begin, for among these people numerous written records remain. The growth habit, ecology, cultivation and utilization of willows was well— understood by Theophrastus, Ovid, Herodotus, Pliny and Dioscorides. Virgil was also quite familiar with willow, e.g. Damoetas complains that: “Galatea, saucy girl, pelts me with apples and then runs off to the willows”. ECLOGIJE III and of foraging bees: “Far and wide they feed on arbutus, pale-green willows, on cassia and ruddy crocus .. .“ GEORGICS IV Theophrastus of Eresos (370—285 B.C.) discussed many aspects of willows throughout his Enquiry into Plants including habitats, wood quality, coppicing and a variety of uses. Willows, according to Theophrastus are lovers of wet places and marshes. But he also notes certain amphibious traits of willows growing in mountains and plains. To Theophrastus they appeared to possess no fruits and quite adequately reproduced themselves from roots, were tolerant to flooding and frequent coppicing. “Even willows grow old and when they are cut, no matter at what height, they shoot up again.” He described the wood as cold, tough, light and resilient—qualities which made it useful for a variety of purposes, especially shields. Such were the diverse virtues of willow that he suggested introducing it for plant husbandry. Theophrastus noted there were many different kinds of willows; three of the best known being black willow (Salix fragilis), white willow (S. -

Salix L.) in the European Alps

diversity Review The Evolutionary History, Diversity, and Ecology of Willows (Salix L.) in the European Alps Natascha D. Wagner 1 , Li He 2 and Elvira Hörandl 1,* 1 Department of Systematics, Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants (with Herbarium), University of Goettingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 2 College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The genus Salix (willows), with 33 species, represents the most diverse genus of woody plants in the European Alps. Many species dominate subalpine and alpine types of vegetation. Despite a long history of research on willows, the evolutionary and ecological factors for this species richness are poorly known. Here we will review recent progress in research on phylogenetic relation- ships, evolution, ecology, and speciation in alpine willows. Phylogenomic reconstructions suggest multiple colonization of the Alps, probably from the late Miocene onward, and reject hypotheses of a single radiation. Relatives occur in the Arctic and in temperate Eurasia. Most species are widespread in the European mountain systems or in the European lowlands. Within the Alps, species differ eco- logically according to different elevational zones and habitat preferences. Homoploid hybridization is a frequent process in willows and happens mostly after climatic fluctuations and secondary contact. Breakdown of the ecological crossing barriers of species is followed by introgressive hybridization. Polyploidy is an important speciation mechanism, as 40% of species are polyploid, including the four endemic species of the Alps. Phylogenomic data suggest an allopolyploid origin for all taxa analyzed Citation: Wagner, N.D.; He, L.; so far. -

Salix × Meyeriana (= Salix Pentandra × S

Phytotaxa 22: 57–60 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Correspondence PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) Salix × meyeriana (= Salix pentandra × S. euxina)―a forgotten willow in Eastern North America ALEXEY G. ZINOVJEV 9 Madison Ave., Randolph, MA 02368, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Salix pentandra L. is a boreal species native to Europe and western Siberia. In North America it is considered to have been introduced to about half of the US states (Argus 2007, 2010). In Massachusetts it is reported from nine of the fourteen counties (Sorrie & Somers 1999). Even though this plant may have been introduced to the US and Canada, its naturalization in North America appears to be quite improbable. Unlike willows from the related section Salix, in S. pentandra twigs are not easily broken off and their ability to root is very low, 0–15% (Belyaeva et al. 2006). It is possible to propagate S. pentandra from softwood cuttings (Belyaeva et al. 2006) and it can be cultivated in botanical gardens, however, vegetative reproduction of this species by natural means seems less likely. In North America this willow is known only by female (pistillate) plants (Argus 2010), so for this species, although setting fruit, sexual reproduction should be excluded. It is difficult to imagine that, under these circumstances, it could escape from cultivation. Therefore, most of the records for this willow in North America should be considered as collections from cultivated plants or misidentifications (Zinovjev 2008–2010). Salix pentandra is known to hybridize with willows of the related section Salix. -

3.2.2.11. Familia Salicaceae (Incluyendo a Flacourtiaceae) 3.2.2.11.A

97 3.2.2.11. Familia Salicaceae (incluyendo a Flacourtiaceae) 3.2.2.11.a. Características ¾ Porte: arbustos o árboles. ¾ Hojas: alternas, simples, con estípulas, en general caducas. ¾ Flores: pequeñas, imperfectas, diclino-dioicas, en amentos erguidos o péndulos. En Azara, Cassearia, Banara, Xylosma pequeñas, solitarias, axilares o en cimas, perfectas o imperfectas, hipóginas, raro períginas o epíginas. ¾ Perianto: aperiantadas, protegidas por una bráctea, con un cáliz vestigial, en Salix se reduce a nectarios. En Azara, Cassearia, Banara, Xylosma cáliz con 3-15 sépalos libres; corola, 3-15 pétalos, disco nectarífero intrastaminal o extraestaminal. ¾ Estambres: 2-varios. En Azara, Cassearia, Banara, Xylosma 4-∞, libres, anteras ditecas. ¾ Gineceo: ovario súpero, 2-10 carpelos unidos, unilocular, pluriovulado, óvulos 1-∞, parietales, estilos libres, parcialmente soldados o estilo único, estigmas. ¾ Fruto: cápsula dehiscente conteniendo semillas lanosas. En Azara, Cassearia, Banara, Xylosma baya, cápsula loculicida o drupa. ¾ Semillas: con pelos, sin endosperma y con embrión recto. Azara, Cassearia, Banara, Xylosma semillas ariladas. Flor estaminada, flor pistilada, brácteas y nectario de la flor estaminada de Salix caroliniana Flor estaminada y flor pistilada de Azara microphylla (Dibujos adaptados de Boelcke y Vizinis, 1987 por Daniel Cian) Diversidad Vegetal Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales y Agrimensura (UNNE) EUDICOTILEDONEAS ESCENCIALES-Clado Rosides-Eurosides I-Malpighiales: Salicaceae (inc. Flacourtiaceae) 98 3.2.2.11.b. Biología floral y/o Fenología La polinización puede ser anemófila, en Populus, o por insectos atraídos por el néctar, que producen los nectarios, ubicados en la base de la flor. Especies del género Salix son polinizadas por abejas melíferas. En las especies entomófilas los órganos nectaríferos son foliares, residuos del perianto que desapareció (Vogel, com. -

Name Clarification: Salix Babylonica L. Vs. S. Matsudana Koidz

Name clarification: Salix babylonica L. vs. S. matsudana Koidz. Fact Sheet No 4 July 2018 Yulia A. Kuzovkina1 and Irina V. Belyaeva2 1Department of Plant Science and Landscape Architecture, Unit-4067, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-4067, USA 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, TW9 3AE, UK The two binominals – S. babylonica L. vs. S. matsudana Koidz. – are frequently used interchangeably in references, scientific publications and catalogs. This discrepancy stems from a difference of opinion on the circumscription or the relationships of the taxa among taxonomists who fall into two camps. In some cases S. matsudana is considered to be the synonym of S. babylonica, and in other cases, these two names denote two different species. Salix babylonica ‘Tortuosa’, dragon’s claw willow or curly willow, an ornamental cultivar with contorted stems. Photo courtesy of M. Dodge, Vermont Willow Nursery. 1 Salix matsudana was described by Koidzumi (1915) referring to the non-weeping taxon from China. This segregation was followed by Rehder (1927, 1940, 1949) who treated “less weeping selections” from China as S. matsudana. Fang et al. (1999), Ohashi (2001) also remarked that the unique characteristics of S. matsudana merit recognition as a distinct species apart from S. babylonica. Another group of botanists, including Skvortsov (1999), Santamour and McArdle (1988) believe that there is little evidence to substantiate the notion of the separation of the two species, and that it is biologically more sensible to regard S. matsudana as synonymous with S. babylonica. In their recent publication Ohashi and Yonekura (2015) regarded S. matsudana as conspecific with S. babylonica and treated it newly as a variety, S . -

Phylogeny of Rosids

Wind-pollinated Rosids Fabids Part I Announcements Lab Quiz today. Lecture review Tuesday, 3-4pm, HCK 320. Lecture Exam Wednesday. Arboretum Field Trip Wednesday. Phylogeny of angiosperms Angiosperms “Basal angiosperms” Parallel venation scattered vascular bundles 1 cotyledon Tricolpate pollen vessels (Jansen et al. 2007) Phylogeny of Eudicots (or Tricolpates) Eudicots (or Tricolpates) “Basal eudicots” (Soltis et al. 2011) Phylogeny of Rosids Rosids Saxifragales Saxifragaceae Crassulaceae Fabids: Malvids: Malpighiales Brassicales Salicaceae Brassicaceae Violaceae Malvales Euphorbiaceae Fabales Malvaceae Sapindales Fabaceae Rosales Aceraceae Myrtales Rosaceae Fagales Onagraceae Betulaceae Geraniales Fagaceae Geraniaceae (The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2009) Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) http://www.blankees.com/house/plants/image/kalanchoe.jpg Kalanchoe sp. Echeveria derenbergii Echeveria sp. http://www.smgrowers.com/imagedb/Echeveria_derenbergii.JPG http://micheleroohani.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/succulent-echeveria-michele-roohani-huntington.jpg Crassulacean Acid Metabolism http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/biology/phoc.html#c4 Green Roofs http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedum Sedum acre biting stonecrop http://ecobrooklyn.com/extensive-green-roof/ Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) 35 genera, 1500 species (Crassula, Echeveria, Kalanchoe, Sedum) Habit: Stem: Leaves: Tim Hagan 2006 Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) Inflorescence: Flowers: Tim Hagan 2003 Sex of plant: Rod Gilbert 2006 Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) Textbook -

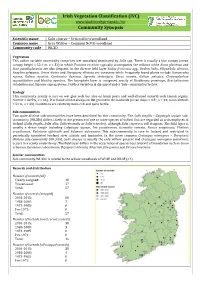

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) Community Synopsis

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) www.biodiversityireland.ie/ivc Community Synopsis Scientific name Salix cinerea – Urtica dioica woodland Common name Grey Willow – Common Nettle woodland Community code WL3D Vegetation This rather variable community comprises wet woodland dominated by Salix spp. There is usually a low canopy (mean canopy height = 12.4 m, n = 32) in which Fraxinus excelsior typically accompanies the willows while Alnus glutinosa and Acer pseudoplatanus are also frequent. In the diverse field layer Rubus fruticosus agg., Hedera helix, Filipendula ulmaria, Angelica sylvestris, Urtica dioica and Dryopteris dilatata are constants while frequently found plants include Ranunculus repens, Galium aparine, Cardamine flexuosa, Agrostis stolonifera, Carex remota, Galium palustre, Chrysosplenium oppositifolium and Mentha aquatica. The bryophyte layer is composed mostly of Kindbergia praelonga, Brachythecium rutabulum and Hypnum cupressiforme. Further variation is discussed under ‘Sub-communities’ below. Ecology This community mainly occurs on wet gley soils but also on basin peats and well-drained mineral soils (mean organic content = 40.5%, n = 33). It is found almost always on flat ground in the lowlands (mean slope = 0.5°, n = 33; mean altitude = 51 m, n = 33). Conditions are relatively base-rich and quite fertile. Sub-communities Two quite distinct sub-communities have been described for this community. The Salix fragilis – Calystegia sepium sub- community (WL3Di) differs chiefly in the presence of one or more species of willow that are regarded as archaeophytes in Ireland (Salix fragilis, Salix alba, Salix viminalis or Salix triandra), although Salix cinerea is still frequent. The field layer is usually a dense tangle including Calystegia sepium, Iris pseudacorus, Oenanthe crocata, Rumex sanguineus, Phalaris arundinacea, Valeriana officinalis and Solanum dulcamara. -

Logan River at Rendezvous Park, Channel and Floodplain Restoration: Crack Willow (Salix Fragilis) Issues and Management Strategi

Logan River at Rendezvous Park, Channel and Floodplain Restoration: Crack Willow (Salix fragilis) Issues and Management Strategies Prepared May 2, 2017 by Darren Olsen, BIO-WEST, Inc. Issues Crack willow is a deciduous multi-stem tree that grows 50 to 80 feet tall and 1 to 3 feet in diameter. Its name comes from the audible ‘crack’ that occurs when branches break and fall. Easily propagated from broken twigs, this species was brought to North America from Eurasia during Colonial times, and now is invading riverine habitats in Logan, Utah. It escaped cultivation (intended plantings) and spreads easily from twigs and root suckers. Crack willow is considered invasive in 9 States, including Utah. Originally grown as individual trees in parks for fast growing shade and firewood, crack willow has spread along Cache Valley waterways into monoculture thickets. Crack willow expansion is effectively replacing many native riparian species, dominating the form and function of river channels, and impacting floodplain functions in all Cache Valley rivers. Crack willow thickets appear naturalized because the trees look old and half dead, however most trees are only 30 to 50 years old. Top ten reasons why crack willow thickets are a problem along the Logan River: • Grows rapidly and consumes large quantities of water • Creates dense closed canopy monoculture thickets • Eliminates protective grasses, sedges, rushes, and forbs from growing on streambanks • Replaces smaller more functional native shrubs, including species such as coyote willow, yellow willow, -

Floral Scent in Salix L. and the Role of Olfactory and Visual Cues for Pollinator Attraction of Salix Caprea L

Floral Scent in Salix L. and the Role of Olfactory and Visual Cues for Pollinator Attraction of Salix caprea L. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Vorgelegt der Fakultät für Biologie, Chemie und Geowissenschaften der Universität Bayreuth von Ulrike Füssel Bayreuth, im Oktober 2007 II Die Arbeit wurde von August 2004 bis Oktober 2007 am Ökologisch-Botanischen Garten der Universität Bayreuth in der Arbeitsgruppe von Herrn PD Dr. Gregor Aas angefertigt. Gefördert wurde die vorliegende Arbeit durch ein Stipendium der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (Graduiertenkolleg 678 – Ökologische Bedeutung von Wirk- und Signalstoffen bei Insekten – von der Struktur zur Funktion). Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Biologie, Chemie und Geowissenschaften der Universität genehmigten Disseration zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.). Tag der Einreichung: 24. Oktober 2007 Tag des Kolloquiums: 09. Januar 2008 Prüfungsausschuss PD Dr. G. Aas (Erstgutachter) Prof. Dr. K. H. Hoffmann (Zweitgutachter) Prof. Dr. K. Dettner (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. S. Liede-Schumann Prof. Dr. R. Schobert III This dissertation is submitted as a “Cumulative Thesis“ that includes four (4) publications: two (2) published articles, one (1) submitted article, and one (1) article in preparation for submission. The publications are listed in detail below. Published: • Dötterl S., Füssel U., Jürgens A., and Aas G. (2005): 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, a floral scent compound in willows that attracts an oligolectic bee. Journal of Chemical Ecology 31:2993-2998 (Part B, Chapter 3). • Füssel U., Dötterl S., Jürgens A., and Aas G. (2007): Inter- and intraspecific variation in floral scent in the genus Salix and its implication for pollination. Journal of Chemical Ecology 33:749-765 (Part B, Chapter 1). -

Salix Diversity in Belgium and the Netherlands: the Use of Traditional Basketry As a Key Factor

Skvortsovia: 5(3): 42-55 (2020) Skvortsovia ISSN 2309-6497 (Print) Copyright: © 2020 Russian Academy of Sciences http://skvortsovia.uran.ru/ ISSN 2309-6500 (Online) Symposium proceedings Salix diversity in Belgium and the Netherlands: the use of traditional basketry as a key factor Arnout Zwaenepoel WVI (West-Vlaamse Intercommunale), Baron Ruzettelaan 35, 8310 Bruges, Belgium [email protected] Received: 14 August 2019 | Accepted by Irina Belyaeva: 8 January 2020 | Published online: 10 January 2020 Edited by: Irina Kadis, Irina Belyaeva and Keith Chamberlain Abstract In Belgium and the Netherlands more than 60 willow species, hybrids and varieties are found, of which only a limited number are native species. The majority were introduced, mainly in the 19th century, as osiers for basketry or hoop-making purposes. Since 1997 the author has tried to identify the willow diversity in Belgium and the Netherlands. In 2019 we have a good idea of the diversity, but a number of names are still uncertain due to taxonomical discussions typical for this difficult genus, with many hybrids, back-crosses and clonal cultivars. Genetic research in the future will probably resolve some of these problems. Keywords: basketry, Belgium, native and escaped willows, Netherlands, Salix diversity Introduction In Belgium and the Netherlands more than 60 willow species, hybrids and varieties are found, of which only a limited number are native species. The majority were introduced, mainly in the 19th century, as osiers for basketry or hoop-making purposes. This article gives a rough overview of the wild or escaped willow taxa in both countries. The diversity of clonal cultivars is not considered in detail.