Cultivated Willows Would Not Be Appropriate Without Mention of the ‘WEEPING WILLOW’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phytoremediation of a Highly Creosote- Contaminated Soil by Means of Salix Viminalis

International Poplar Commission Phytoremediation of a highly creosote- contaminated soil by means of Salix viminalis Karin Önneby1, Leticia Pizzul1 and Ulf Granhall1 Mauritz Ramstedt 1Department of Microbiology, SLU, P.O. Box 7025, 75007 Uppsala, SWEDEN Email:E-mail: mauritz.ramstedt@m [email protected] Objective To study the effect of willow (Salix viminalis) on the degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a highly creosote-contaminated soil. Results 1600 The presence of S. viminalis enhanced 1400 Initial degradation of all the studied PAHs (Fig. 1). 1200 The highest dissipations were observed for Without plant 1000 With plant fluoranthene (79%) and pyrene (77%). For 800 those compounds, some degradation also 600 occurred in pots without plants, 35 and 19% 400 Concentration (mg/kg dw) Concentration respectively. Degradation of anthracene 200 (67%) and benzo[a]pyrene (43%) was found 0 Anthracene Fluoranthene Pyrene Benzo[a]pyrene only in pots with S. viminalis. Fig. 1. PAH concentrations in the creosote-contaminated soil, initially and after 10 weeks of treatment with or without plant. 4000000 The higher number of bacteria in the 3000000 treatments with plants, compared to the initial soil and the soil without plants (Fig. 2) 2000000 indicates an increase in microbial activity. CFU (dw) /g soil 1000000 This activity, and possibly a higher release of biosurfactants, could explain the enhanced 0 degradation obtained with plants. Initial Without plant With plant Fig. 2. Bacterial number (CFU/g dry soil) in the creosote- contaminated soil, initially and after 10 weeks of treatment with or without plant. Conclusions and future perspectives The use of S. -

Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment / Edited by J.G

Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment This volume is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Victor Steenackers. Vic, as he was known to his friends, was born in Weelde, Belgium, in 1928. His life was devoted to his family – his wife, Joanna, his 9 children and his 23 grandchildren. His career was devoted to the study and improve- ment of poplars, particularly through poplar breeding. As Director of the Poplar Research Institute at Geraardsbergen, Belgium, he pursued a lifelong scientific interest in poplars and encouraged others to share his passion. As a member of the Executive Committee of the International Poplar Commission for many years, and as its Chair from 1988 to 2000, he was a much-loved mentor and powerful advocate, spreading scientific knowledge of poplars and willows worldwide throughout the many member countries of the IPC. This book is in many ways part of the legacy of Vic Steenackers, many of its contributing authors having learned from his guidance and dedication. Vic Steenackers passed away at Aalst, Belgium, in August 2010, but his work is carried on by others, including mem- bers of his family. Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment Edited by J.G. Isebrands Environmental Forestry Consultants LLC, New London, Wisconsin, USA and J. Richardson Poplar Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CABI CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Tel: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. -

The Effects of DNA Methylation Inhibition on Flower Development in the Dioecious Plant Salix Viminalis

Article The Effects of DNA Methylation Inhibition on Flower Development in the Dioecious Plant Salix Viminalis Yun-He Cheng 1,2 , Xiang-Yong Peng 3, Yong-Chang Yu 1,2, Zhen-Yuan Sun 1,2 and Lei Han 1,2,* 1 Research Institute of Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing 100193, China; [email protected] (Y.-H.C.); [email protected] (Y.-C.Y.); [email protected] (Z.-Y.S.) 2 Key Laboratory of Tree Breeding and Cultivation, State Forestry Administration, Beijing 100193, China 3 Life and Science College, Qufu Normal University, Qufu 273100, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-010-62889652 Received: 25 January 2019; Accepted: 16 February 2019; Published: 18 February 2019 Abstract: DNA methylation, an important epigenetic modification, regulates the expression of genes and is therefore involved in the transitions between floral developmental stages in flowering plants. To explore whether DNA methylation plays different roles in the floral development of individual male and female dioecious plants, we injected 5-azacytidine (5-azaC), a DNA methylation inhibitor, into the trunks of female and male basket willow (Salix viminalis L.) trees before flower bud initiation. As expected, 5-azaC decreased the level of DNA methylation in the leaves of both male and female trees during floral development; however, it increased DNA methylation in the leaves of male trees at the flower transition stage. Furthermore, 5-azaC increased the number, length and diameter of flower buds in the female trees but decreased these parameters in the male trees. The 5-azaC treatment also decreased the contents of soluble sugars, starch and reducing sugars in the leaves of the female plants, while increasing them in the male plants at the flower transition stage; however, this situation was largely reversed at the flower development stage. -

Tree Planting and Management

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION Tree Planting and Management Breadth of Opportunity The spread of the Commission's responsibilities over some 148 countries in temperate, mediterranean, tropical and desert climates provides wonderful opportunities to experiment with nature's wealth of tree species. We are particularly fortunate in being able to grow many interesting and beautiful trees and we will explain how we manage them and what splendid specimens they can make. Why Plant Trees? Trees are planted for a variety of reasons: their amenity value, leaf shape and size, flowers, fruit, habit, form, bark, landscape value, shelter or screening, backcloth planting, shade, noise and pollution reduction, soil stabilisation and to encourage wild life. Often we plant trees solely for their amenity value. That is, the beauty of the tree itself. This can be from the leaves such as those in Robinia pseudoacacia 'Frisia', the flowers in the tropical tree Tabebuia or Albizia, the crimson stems of the sealing wax palm (Cyrtostachys renda), or the fruit as in Magnolia grandiflora. above: Sealing wax palms at Taiping War Cemetery, Malaysia with insert of the fruit of Magnolia grandiflora Selection Generally speaking the form of the left: The tropical tree Tabebuia tree is very often a major contributing factor and this, together with a sound knowledge of below: Flowers of the tropical the situation in which the tree is to tree Albizia julibrissin be grown, guides the decision to the best choice of species. Exposure is a major limitation to the free choice of species in northern Europe especially and trees such as Sorbus, Betula, Tilia, Fraxinus, Crataegus and fastigiate yews play an important role in any landscape design where the elements are seriously against a wider selection. -

Salix L.) in the European Alps

diversity Review The Evolutionary History, Diversity, and Ecology of Willows (Salix L.) in the European Alps Natascha D. Wagner 1 , Li He 2 and Elvira Hörandl 1,* 1 Department of Systematics, Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants (with Herbarium), University of Goettingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 2 College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The genus Salix (willows), with 33 species, represents the most diverse genus of woody plants in the European Alps. Many species dominate subalpine and alpine types of vegetation. Despite a long history of research on willows, the evolutionary and ecological factors for this species richness are poorly known. Here we will review recent progress in research on phylogenetic relation- ships, evolution, ecology, and speciation in alpine willows. Phylogenomic reconstructions suggest multiple colonization of the Alps, probably from the late Miocene onward, and reject hypotheses of a single radiation. Relatives occur in the Arctic and in temperate Eurasia. Most species are widespread in the European mountain systems or in the European lowlands. Within the Alps, species differ eco- logically according to different elevational zones and habitat preferences. Homoploid hybridization is a frequent process in willows and happens mostly after climatic fluctuations and secondary contact. Breakdown of the ecological crossing barriers of species is followed by introgressive hybridization. Polyploidy is an important speciation mechanism, as 40% of species are polyploid, including the four endemic species of the Alps. Phylogenomic data suggest an allopolyploid origin for all taxa analyzed Citation: Wagner, N.D.; He, L.; so far. -

Salix × Meyeriana (= Salix Pentandra × S

Phytotaxa 22: 57–60 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Correspondence PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) Salix × meyeriana (= Salix pentandra × S. euxina)―a forgotten willow in Eastern North America ALEXEY G. ZINOVJEV 9 Madison Ave., Randolph, MA 02368, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Salix pentandra L. is a boreal species native to Europe and western Siberia. In North America it is considered to have been introduced to about half of the US states (Argus 2007, 2010). In Massachusetts it is reported from nine of the fourteen counties (Sorrie & Somers 1999). Even though this plant may have been introduced to the US and Canada, its naturalization in North America appears to be quite improbable. Unlike willows from the related section Salix, in S. pentandra twigs are not easily broken off and their ability to root is very low, 0–15% (Belyaeva et al. 2006). It is possible to propagate S. pentandra from softwood cuttings (Belyaeva et al. 2006) and it can be cultivated in botanical gardens, however, vegetative reproduction of this species by natural means seems less likely. In North America this willow is known only by female (pistillate) plants (Argus 2010), so for this species, although setting fruit, sexual reproduction should be excluded. It is difficult to imagine that, under these circumstances, it could escape from cultivation. Therefore, most of the records for this willow in North America should be considered as collections from cultivated plants or misidentifications (Zinovjev 2008–2010). Salix pentandra is known to hybridize with willows of the related section Salix. -

List of Publications —MARIA GREGER

List of Publications —MARIA GREGER Scientific Publications (Paper with review system = R; Included in thesis = X) 1. RX Greger M. & Lindberg S., 1986. Effects of Cd2+ and EDTA on young sugar beets (Beta vulgaris). I. Cd2+uptake and sugar accumulation. — Physiologia Plantarum 66: 69-74. 2. RX Greger M. & Lindberg S., 1987. Effects of Cd2+ and EDTA on young sugar beets (Beta vulgaris). II. Net uptake and distribution of Mg2+, Ca2+ and Fe2+/Fe3+. — Physiologia Plantarum 69: 81-86. 3. RX Greger M., 1989. Cadmium Effects on Carbohydrate Metabolism in Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris). — Thesis, Stockholm University, ISBN 91-7146-717-3 4. R Kronestedt-Robards E. C., Greger M. & Robards A. W., 1989. The nectar of the Strelizia Reginæ flower. — Physiologia Plantarum 77: 341-346. 5. R X Greger M., Brammer E. S., Lindberg S., Larsson G. & Idestam-Almquist J., 1991. Uptake and physiological effects of cadmium in sugar beets (Beta vulgaris) related to mineral provision. — Journal of Experimental Botany 42: 729-737. 6. R Lindberg S., Szynkier K. & Greger M., 1991. Aluminum effects on transmembrane potential in cells of fibrous roots of sugar beet. — Physiologia Plantarum 83: 54-62. 7. R X Greger M. & Ögren E., 1991. Direct and indirect effects of Cd2+ on the photosynthesis and CO2-assimilation in sugar beets (Beta vulgaris). — Physiologia Plantarum 83: 129-135. 8. R Greger M. & Kautsky L., 1991. Effects of Cu, Pb, and Zn on two species of Potamogeton grown in field conditions. — Vegetatio 97: 173-184. 9. R X Greger M. & Bertell G., 1992. Effects of Ca2+ and Cd2+ on the carbohydrate metabolism in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris). -

Phytoremediation of Metal Contamination Using Salix (Willows)

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2015 Phytoremediation of Metal Contamination Using Salix (Willows) Gordon J. Kersten University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Kersten, Gordon J., "Phytoremediation of Metal Contamination Using Salix (Willows)" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1034. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1034 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Phytoremediation of Metal Contamination using Salix (willows) ______________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics University of Denver ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science ______________________ By Gordon J. Kersten August 2015 Advisor: Martin F. Quigley Author: Gordon J. Kersten Title: Phytoremediation of Metal Contamination using Salix (willows) Advisor: Martin F. Quigley Degree Date: August 2015 ABSTRACT Abandoned hardrock mines and the resulting Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) are a source of vast, environmental degradation that are toxic threats to plants, animals, and humans. Cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) are metal contaminants often found in AMD. In my mine outwash water samples, cadmium and lead concentrations were 19 and 160 times greater than concentrations in control waterways, and 300 and 40 times greater than EPA Aquatic Life Use water quality standards, respectively. -

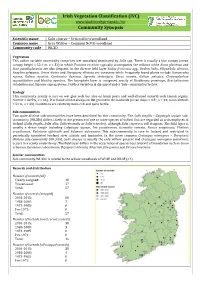

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) Community Synopsis

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) www.biodiversityireland.ie/ivc Community Synopsis Scientific name Salix cinerea – Urtica dioica woodland Common name Grey Willow – Common Nettle woodland Community code WL3D Vegetation This rather variable community comprises wet woodland dominated by Salix spp. There is usually a low canopy (mean canopy height = 12.4 m, n = 32) in which Fraxinus excelsior typically accompanies the willows while Alnus glutinosa and Acer pseudoplatanus are also frequent. In the diverse field layer Rubus fruticosus agg., Hedera helix, Filipendula ulmaria, Angelica sylvestris, Urtica dioica and Dryopteris dilatata are constants while frequently found plants include Ranunculus repens, Galium aparine, Cardamine flexuosa, Agrostis stolonifera, Carex remota, Galium palustre, Chrysosplenium oppositifolium and Mentha aquatica. The bryophyte layer is composed mostly of Kindbergia praelonga, Brachythecium rutabulum and Hypnum cupressiforme. Further variation is discussed under ‘Sub-communities’ below. Ecology This community mainly occurs on wet gley soils but also on basin peats and well-drained mineral soils (mean organic content = 40.5%, n = 33). It is found almost always on flat ground in the lowlands (mean slope = 0.5°, n = 33; mean altitude = 51 m, n = 33). Conditions are relatively base-rich and quite fertile. Sub-communities Two quite distinct sub-communities have been described for this community. The Salix fragilis – Calystegia sepium sub- community (WL3Di) differs chiefly in the presence of one or more species of willow that are regarded as archaeophytes in Ireland (Salix fragilis, Salix alba, Salix viminalis or Salix triandra), although Salix cinerea is still frequent. The field layer is usually a dense tangle including Calystegia sepium, Iris pseudacorus, Oenanthe crocata, Rumex sanguineus, Phalaris arundinacea, Valeriana officinalis and Solanum dulcamara. -

(Salix) Using Ovule Numbers

75 Marchenko and Kuzovkina . Silvae Genetica (2021) 70, 75 - 83 Identification of hybrid formulae of a few willows (Salix) using ovule numbers Аlexander M. Marchenko1 and Yulia A. Kuzovkina2* 1 Russian Park of Water Gardens, Moscow, Russia 2 Department of Plant Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA * Corresponding author: Yulia A. Kuzovkina, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract individual plant does not provide the full range of reproductive structures that are important for identification. The nonconcur- Salix is a genus of considerable taxonomic complexity, and rent phenology of generative and vegetative structures makes accurate identification of its species and hybrids is not always it impossible to observe both morphological characters on one possible. Quantification of ovules was used in this study to plant at the same time. Willow identification is also complica- verify the parentage of a few hybrids of Salix. It has been shown ted by phenotypic variability during different developmental that ovule numbers in willow hybrids are the mean of the ovu- stages (stipules and leaf hairs may appear and disappear le numbers of their parents. The ovule index of a prostrate spe- during the growing season) and habitat conditions (the size cimen of S. ×cottetii affirmed that this was a hybrid ofS. myrsi- and thickness of leaves depends on the degree of exposure to nifolia Salisb. and S. retusa L., and the ovule index of the sunlight) (Skvortsov 1999; Dickmann and Kuzovkina 2014). In ornamental cultivar ‘The Hague’ affirmed that this was a hybrid addition, considerable individual variability and polymor- of S. caprea L. and S. -

Fine Mapping of the Sex Locus in Salix Triandra Confirms a Consistent Sex Determination Mechanism in Genus Salix

Li et al. Horticulture Research (2020) 7:64 Horticulture Research https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-0289-1 www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Open Access Fine mapping of the sex locus in Salix triandra confirms a consistent sex determination mechanism in genus Salix Wei Li1,HuaitongWu1, Xiaoping Li1, Yingnan Chen1 andTongmingYin1 Abstract Salix triandra belongs to section Amygdalinae in genus Salix, which is in a different section from the willow species in which sex determination has been well studied. Studying sex determination in distantly related willow species will help to clarify whether the sexes of different willows arise through a common sex determination system. For this purpose, we generated an intraspecific full-sib F1 population for S. triandra and constructed high-density genetic linkage maps for the crossing parents using restriction site-associated DNA sequencing and following a two-way pseudo-testcross strategy. With the established maps, the sex locus was positioned in linkage group XV only in the maternal map, and no sex linkage was detected in the paternal map. Consistent with previous findings in other willow species, our study showed that chromosome XV was the incipient sex chromosome and that females were the heterogametic sex in S. triandra. Therefore, sex in this willow species is also determined through a ZW sex determination system. We further performed fine mapping in the vicinity of the sex locus with SSR markers. By comparing the physical and genetic distances for the target interval encompassing the sex determination gene confined by SSRs, severe recombination repression was revealed in the sex determination region in the female map. -

Shrub Willow Biomass Producer's Handbook

ShrubShrub WillowWillow BiomassBiomass Producer’sProducer’s HandbookHandbook Planting willow with Step Planter 3-year old willow — ready to harvest Harvesting willow with New Holland forage harvester and willow cutting head One-year old willow Willow catkins SHRUB WILLOW BIOMASS PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK PAGE 2 Shrub Willow Biomass Producer’s Handbook Lawrence P. Abrahamson, Senior Research Associate Timothy A. Volk, Senior Research Associate Lawrence B. Smart1, Associate Professor Kimberly D. Cameron1, Research Scientist State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry 1 Forestry Dr. Syracuse, NY 13210 Revised December 2010 1 now at Cornell University in the Department of Horticultural Sciences, New York State Agricultural Experiment Station in Geneva, NY PAGE 3 SHRUB WILLOW BIOMASS PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK Table of Contents I. Preface……………………………………………………………………………. 4 II. Introduction……………………………………………….………………………. 5 a. Benefits for Growing Willow…………………………………………….. 5 i. Harvesting for Sale to the Energy Market………………………... 5 ii. Incentive Programs for Farmers………………………….. 5 iii. Environmental Benefits and Sustainability………………. 6 b. Cultivation of Shrub Willow: History and Current Prospects……………. 6 III. Soil & Site Considerations for Willow Biomass Crops …………………………. 8 IV. Growing Willow………………………………………………………………... 9 c. Site Preparation, Weed Control and Cover Crops…………………….….. 9 d. Planting………………………………………………………………….. 11 e. First Growing Season…………………………………………………… 14 f. Second through Fourth Growing Seasons………………………………. 16 g.