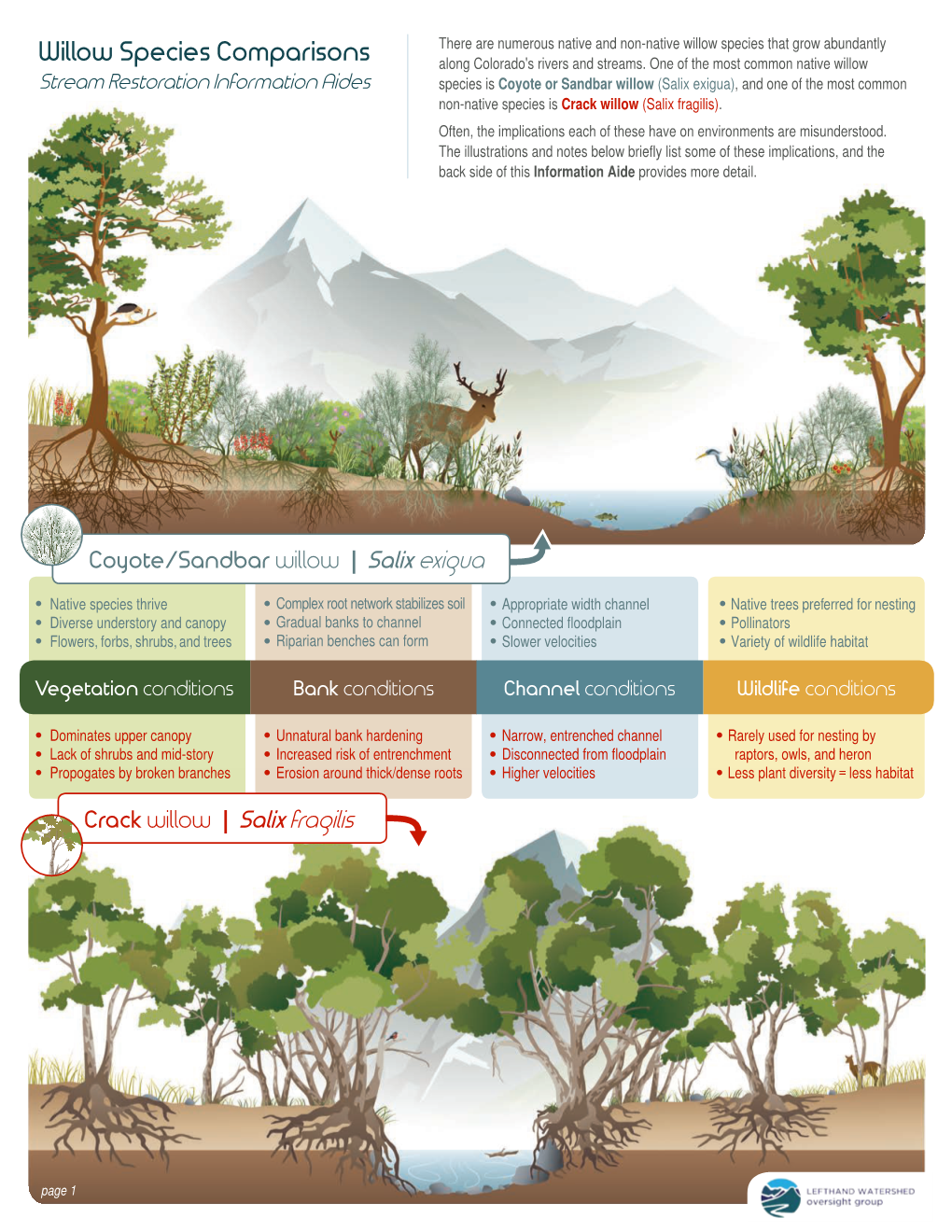

Willow Species Comparisons Along Colorado's Rivers and Streams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Willows of Interior Alaska

1 Willows of Interior Alaska Dominique M. Collet US Fish and Wildlife Service 2004 2 Willows of Interior Alaska Acknowledgements The development of this willow guide has been made possible thanks to funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service- Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge - order 70181-12-M692. Funding for printing was made available through a collaborative partnership of Natural Resources, U.S. Army Alaska, Department of Defense; Pacific North- west Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Department of Agriculture; National Park Service, and Fairbanks Fish and Wildlife Field Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior; and Bonanza Creek Long Term Ecological Research Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks. The data for the distribution maps were provided by George Argus, Al Batten, Garry Davies, Rob deVelice, and Carolyn Parker. Carol Griswold, George Argus, Les Viereck and Delia Person provided much improvement to the manuscript by their careful editing and suggestions. I want to thank Delia Person, of the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, for initiating and following through with the development and printing of this guide. Most of all, I am especially grateful to Pamela Houston whose support made the writing of this guide possible. Any errors or omissions are solely the responsibility of the author. Disclaimer This publication is designed to provide accurate information on willows from interior Alaska. If expert knowledge is required, services of an experienced botanist should be sought. Contents -

COYOTE WILLOW Willow Is Gathered from the Time the Leaves Fall in Autumn Until the Buds Begin to Swell in Spring

COYOTE WILLOW Willow is gathered from the time the leaves fall in autumn until the buds begin to swell in spring. The Salix exigua Nutt. year-old wands without branches are chosen, and plant symbol = SAEX sorted by size and length. The bark can easily be stripped off in the spring when the sap rises. Willow Contributed By: USDA, NRCS, National Plant Data wands with the smallest leaf scars are split and peeled Center, New Mexico Plant Materials Center, & Idaho to obtain the tough, flexible sapwood used for the Plant Materials Center weft in basket weaving. Color variation is achieved by alternating peeled and unpeeled willow sticks in the warp. Ute Indians used to concoct a green dye for coloring buckskin by soaking willow leaves in hot water and then boiling the mixture to concentrate the pigment. Willow roots also have been used by others to manufacture a rose-tan dye. The Paiute built willow-frame houses covered with Alfred Brousseau mats of cattails or tules. Slender willow withes were Brother Eric Vogel, St. Mary’s College @ CalPhotos woven into tight circular fences as protection from the wind that blew sand into eyes and food. For shade, shed roofs thatched with willows, called Alternate Names "willow shadows", were constructed. In the Pueblo Sandbar willow, gray willow, narrow-leaved willow, province, coyote willow branches are employed with dusky willow, pussywillow leaves attached for thatching roofs. Other light construction uses included the tops of storage bins or Uses racks for aerating corn while it dried, such as one Ethnobotanic: The value of willow as the raw recently unearthed at prehistoric Arroyo Hondo material necessary for the manufacture of a family's Pueblo. -

Cultivated Willows Would Not Be Appropriate Without Mention of the ‘WEEPING WILLOW’

Alexander Robertson Notes on willows cultivated in Scotland and a few sketches of willows sampled from my clonal collection HISTORICAL NOTES Since the knowledge of willows is of great antiquity, it is with the ancient Greeks and Romans we shall begin, for among these people numerous written records remain. The growth habit, ecology, cultivation and utilization of willows was well— understood by Theophrastus, Ovid, Herodotus, Pliny and Dioscorides. Virgil was also quite familiar with willow, e.g. Damoetas complains that: “Galatea, saucy girl, pelts me with apples and then runs off to the willows”. ECLOGIJE III and of foraging bees: “Far and wide they feed on arbutus, pale-green willows, on cassia and ruddy crocus .. .“ GEORGICS IV Theophrastus of Eresos (370—285 B.C.) discussed many aspects of willows throughout his Enquiry into Plants including habitats, wood quality, coppicing and a variety of uses. Willows, according to Theophrastus are lovers of wet places and marshes. But he also notes certain amphibious traits of willows growing in mountains and plains. To Theophrastus they appeared to possess no fruits and quite adequately reproduced themselves from roots, were tolerant to flooding and frequent coppicing. “Even willows grow old and when they are cut, no matter at what height, they shoot up again.” He described the wood as cold, tough, light and resilient—qualities which made it useful for a variety of purposes, especially shields. Such were the diverse virtues of willow that he suggested introducing it for plant husbandry. Theophrastus noted there were many different kinds of willows; three of the best known being black willow (Salix fragilis), white willow (S. -

Salix L.) in the European Alps

diversity Review The Evolutionary History, Diversity, and Ecology of Willows (Salix L.) in the European Alps Natascha D. Wagner 1 , Li He 2 and Elvira Hörandl 1,* 1 Department of Systematics, Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants (with Herbarium), University of Goettingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 2 College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The genus Salix (willows), with 33 species, represents the most diverse genus of woody plants in the European Alps. Many species dominate subalpine and alpine types of vegetation. Despite a long history of research on willows, the evolutionary and ecological factors for this species richness are poorly known. Here we will review recent progress in research on phylogenetic relation- ships, evolution, ecology, and speciation in alpine willows. Phylogenomic reconstructions suggest multiple colonization of the Alps, probably from the late Miocene onward, and reject hypotheses of a single radiation. Relatives occur in the Arctic and in temperate Eurasia. Most species are widespread in the European mountain systems or in the European lowlands. Within the Alps, species differ eco- logically according to different elevational zones and habitat preferences. Homoploid hybridization is a frequent process in willows and happens mostly after climatic fluctuations and secondary contact. Breakdown of the ecological crossing barriers of species is followed by introgressive hybridization. Polyploidy is an important speciation mechanism, as 40% of species are polyploid, including the four endemic species of the Alps. Phylogenomic data suggest an allopolyploid origin for all taxa analyzed Citation: Wagner, N.D.; He, L.; so far. -

Salix × Meyeriana (= Salix Pentandra × S

Phytotaxa 22: 57–60 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Correspondence PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) Salix × meyeriana (= Salix pentandra × S. euxina)―a forgotten willow in Eastern North America ALEXEY G. ZINOVJEV 9 Madison Ave., Randolph, MA 02368, USA; E-mail: [email protected] Salix pentandra L. is a boreal species native to Europe and western Siberia. In North America it is considered to have been introduced to about half of the US states (Argus 2007, 2010). In Massachusetts it is reported from nine of the fourteen counties (Sorrie & Somers 1999). Even though this plant may have been introduced to the US and Canada, its naturalization in North America appears to be quite improbable. Unlike willows from the related section Salix, in S. pentandra twigs are not easily broken off and their ability to root is very low, 0–15% (Belyaeva et al. 2006). It is possible to propagate S. pentandra from softwood cuttings (Belyaeva et al. 2006) and it can be cultivated in botanical gardens, however, vegetative reproduction of this species by natural means seems less likely. In North America this willow is known only by female (pistillate) plants (Argus 2010), so for this species, although setting fruit, sexual reproduction should be excluded. It is difficult to imagine that, under these circumstances, it could escape from cultivation. Therefore, most of the records for this willow in North America should be considered as collections from cultivated plants or misidentifications (Zinovjev 2008–2010). Salix pentandra is known to hybridize with willows of the related section Salix. -

COYOTE WILLOW American Baskets

Plant Guide was the material of choice for manufacturing Native COYOTE WILLOW American baskets. Salix exigua Nutt. Willow is gathered from the time the leaves fall in Plant Symbol = SAEX autumn until the buds begin to swell in spring. The year-old wands without branches are chosen, and Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data sorted by size and length. The bark can easily be Center, New Mexico Plant Materials Center, & Idaho stripped off in the spring when the sap rises. Willow Plant Materials Center wands with the smallest leaf scars are split and peeled to obtain the tough, flexible sapwood used for the weft in basket weaving. Color variation is achieved by alternating peeled and unpeeled willow sticks in the warp. Ute Indians used to concoct a green dye for coloring buckskin by soaking willow leaves in hot water and then boiling the mixture to concentrate the pigment. Willow roots also have been used by others Alfred Brousseau to manufacture a rose-tan dye. © Brother Eric Vogel, St. Mary’s College @ CalPhotos The Paiute built willow-frame houses covered with mats of cattails or tules. Slender willow withes were Alternate Names woven into tight circular fences as protection from Sandbar willow, gray willow, narrow-leaved willow, the wind that blew sand into eyes and food. For dusky willow, pussywillow shade, shed roofs thatched with willows, called "willow shadows", were constructed. In the Pueblo Uses province, coyote willow branches are employed with Ethnobotanic: The value of willow as the raw leaves attached for thatching roofs. Other light material necessary for the manufacture of a family's construction uses included the tops of storage bins or household goods cannot be over-estimated. -

Phylogeny of Rosids

Wind-pollinated Rosids Fabids Part I Announcements Lab Quiz today. Lecture review Tuesday, 3-4pm, HCK 320. Lecture Exam Wednesday. Arboretum Field Trip Wednesday. Phylogeny of angiosperms Angiosperms “Basal angiosperms” Parallel venation scattered vascular bundles 1 cotyledon Tricolpate pollen vessels (Jansen et al. 2007) Phylogeny of Eudicots (or Tricolpates) Eudicots (or Tricolpates) “Basal eudicots” (Soltis et al. 2011) Phylogeny of Rosids Rosids Saxifragales Saxifragaceae Crassulaceae Fabids: Malvids: Malpighiales Brassicales Salicaceae Brassicaceae Violaceae Malvales Euphorbiaceae Fabales Malvaceae Sapindales Fabaceae Rosales Aceraceae Myrtales Rosaceae Fagales Onagraceae Betulaceae Geraniales Fagaceae Geraniaceae (The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2009) Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) http://www.blankees.com/house/plants/image/kalanchoe.jpg Kalanchoe sp. Echeveria derenbergii Echeveria sp. http://www.smgrowers.com/imagedb/Echeveria_derenbergii.JPG http://micheleroohani.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/succulent-echeveria-michele-roohani-huntington.jpg Crassulacean Acid Metabolism http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/biology/phoc.html#c4 Green Roofs http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedum Sedum acre biting stonecrop http://ecobrooklyn.com/extensive-green-roof/ Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) 35 genera, 1500 species (Crassula, Echeveria, Kalanchoe, Sedum) Habit: Stem: Leaves: Tim Hagan 2006 Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) Inflorescence: Flowers: Tim Hagan 2003 Sex of plant: Rod Gilbert 2006 Crassulaceae (Stonecrop family) Textbook -

Reference Plant List

APPENDIX J NATIVE & INVASIVE PLANT LIST The following tables capture the referenced plants, native and invasive species, found throughout this document. The Wildlife Action Plan Team elected to only use common names for plants to improve the readability, particular for the general reader. However, common names can create confusion for a variety of reasons. Common names can change from region-to-region; one common name can refer to more than one species; and common names have a way of changing over time. For example, there are two widespread species of greasewood in Nevada, and numerous species of sagebrush. In everyday conversation generic common names usually work well. But if you are considering management activities, landscape restoration or the habitat needs of a particular wildlife species, the need to differentiate between plant species and even subspecies suddenly takes on critical importance. This appendix provides the reader with a cross reference between the common plant names used in this document’s text, and the scientific names that link common names to the precise species to which writers referenced. With regards to invasive plants, all species listed under the Nevada Revised Statute 555 (NRS 555) as a “Noxious Weed” will be notated, within the larger table, as such. A noxious weed is a plant that has been designated by the state as a “species of plant which is, or is likely to be, detrimental or destructive and difficult to control or eradicate” (NRS 555.05). To assist the reader, we also included a separate table detailing the noxious weeds, category level (A, B, or C), and the typical habitats that these species invade. -

Guide to the Willows of Shoshone National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Willows Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station of Shoshone National General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-83 Forest October 2001 Walter Fertig Stuart Markow Natural Resources Conservation Service Cody Conservation District Abstract Fertig, Walter; Markow, Stuart. 2001. Guide to the willows of Shoshone National Forest. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-83. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 79 p. Correct identification of willow species is an important part of land management. This guide describes the 29 willows that are known to occur on the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. Keys to pistillate catkins and leaf morphology are included with illustrations and plant descriptions. Key words: Salix, willows, Shoshone National Forest, identification The Authors Walter Fertig has been Heritage Botanist with the University of Wyoming’s Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) since 1992. He has conducted rare plant surveys and natural areas inventories throughout Wyoming, with an emphasis on the desert basins of southwest Wyoming and the montane and alpine regions of the Wind River and Absaroka ranges. Fertig is the author of the Wyoming Rare Plant Field Guide, and has written over 100 technical reports on rare plants of the State. Stuart Markow received his Masters Degree in botany from the University of Wyoming in 1993 for his floristic survey of the Targhee National Forest in Idaho and Wyoming. He is currently a Botanical Consultant with a research emphasis on the montane flora of the Greater Yellowstone area and the taxonomy of grasses. Acknowledgments Sincere thanks are extended to Kent Houston and Dave Henry of the Shoshone National Forest for providing Forest Service funding for this project. -

Chelone Obliqua Pennell & Wherry Purplepurple Turtlehead Turtlehead, Page 1

Chelone obliqua Pennell & Wherry purplepurple turtlehead turtlehead, Page 1 State Distribution Photo by Michael R. Penskar Best Survey Period Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Status: Endangered State distribution: C. obliqua is known in Michigan only from Washtenaw County, where it has been Global and state rank: G4/S1 documented as extant at four sites ranging from a Dexter metro park locality to an occurrence recently Other common names: Pink turtlehead; rose discovered near the western border of Ypsilanti. This turtlehead species was collected in the Ann Arbor vicinity as early as 1904, and again in 1922. At least one of those Family: Scrophulariaceae (snapdragon family) localities was east of Ann Arbor and may be represented by the Ypsilanti locality. All of the extant sites occur Taxonomy: Our plants belong to var. speciosa, which along the Huron River, and there is a strong likelihood intergrades in the Mississippi embayment with the more that additional colonies exist owing to the presence coastal var. obliqua. Morphological and molecular of considerable potential habitat both downriver and research to analyze the evolutionary relationships within upriver from the known localities. Tribe Cheloneae, which includes C. obliqua, has been conducted by Nelson and Elisens (1999) and Wolfe et Recognition: Purple turtlehead is a tall, perennial forb al. (1997). that ranges from ca. 3-7 dm or more in height, with opposite, short stalked, narrowly lance-shaped leaves Total range: Purple turtlehead in the broad sense that are elongate (commonly over 20 cm) and sharply (Chelone obliqua var. obliqua) occurs on the Atlantic saw-toothed. -

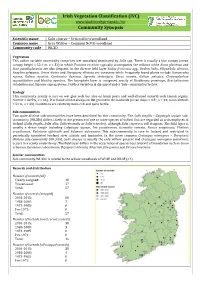

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) Community Synopsis

Irish Vegetation Classification (IVC) www.biodiversityireland.ie/ivc Community Synopsis Scientific name Salix cinerea – Urtica dioica woodland Common name Grey Willow – Common Nettle woodland Community code WL3D Vegetation This rather variable community comprises wet woodland dominated by Salix spp. There is usually a low canopy (mean canopy height = 12.4 m, n = 32) in which Fraxinus excelsior typically accompanies the willows while Alnus glutinosa and Acer pseudoplatanus are also frequent. In the diverse field layer Rubus fruticosus agg., Hedera helix, Filipendula ulmaria, Angelica sylvestris, Urtica dioica and Dryopteris dilatata are constants while frequently found plants include Ranunculus repens, Galium aparine, Cardamine flexuosa, Agrostis stolonifera, Carex remota, Galium palustre, Chrysosplenium oppositifolium and Mentha aquatica. The bryophyte layer is composed mostly of Kindbergia praelonga, Brachythecium rutabulum and Hypnum cupressiforme. Further variation is discussed under ‘Sub-communities’ below. Ecology This community mainly occurs on wet gley soils but also on basin peats and well-drained mineral soils (mean organic content = 40.5%, n = 33). It is found almost always on flat ground in the lowlands (mean slope = 0.5°, n = 33; mean altitude = 51 m, n = 33). Conditions are relatively base-rich and quite fertile. Sub-communities Two quite distinct sub-communities have been described for this community. The Salix fragilis – Calystegia sepium sub- community (WL3Di) differs chiefly in the presence of one or more species of willow that are regarded as archaeophytes in Ireland (Salix fragilis, Salix alba, Salix viminalis or Salix triandra), although Salix cinerea is still frequent. The field layer is usually a dense tangle including Calystegia sepium, Iris pseudacorus, Oenanthe crocata, Rumex sanguineus, Phalaris arundinacea, Valeriana officinalis and Solanum dulcamara. -

Blueberry Willow): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Salix myrtillifolia Anderss. (blueberry willow): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project June 29, 2006 Stephanie L. Neid, Ph.D., Karin Decker, and David G. Anderson Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Neid, S.L., K. Decker, and D.G. Anderson. (2006, June 29). Salix myrtillifolia Anderss. (blueberry willow): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/salixmyrtillifolia.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was greatly facilitated by the helpfulness and generosity of many experts, particularly George Argus, Robert Dorn, Bud Kovalchik, Steve Brunsfield, John Sanderson, and Barry Johnston. Their interest in the project, valuable insight, depth of experience, and time spent answering questions were extremely valuable and crucial to the project. Herbarium specimen label data were provided by Tim Hogan (COLO), Ron Hartman and Ernie Nelson (RM), and Janet Wingate (KDH). Thanks also to Cathy Cripps, Bonnie Heidel, George Jones, Chris Chappel, Rex Crawford, Florence Caplow, Scott Mincemoyer, Andy Kratz, Kathy Carsey, and Beth Burkhart for assisting with questions and project management. Jane Nusbaum, Dawn Taylor, and Barbara Brayfield provided crucial financial oversight. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Stephanie L. Neid is an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP). Her work at CNHP includes ecological inventory and assessment throughout Colorado, beginning in 2004. Prior to this, she was an ecologist with the New Hampshire Natural Heritage Bureau and the Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program and was a Regional Vegetation Ecologist for NatureServe.