A Japanese Perspective on North Korea: Troubled Bilateral Relations in a Complex Multilateral Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS for EAST ASIA Toward

Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS FOR EAST ASIA Toward Greater U.S.-Japan-India Strategic Dialogue and Coordination Mike Green Arc of Freedom and Prosperity Heigo Sato India’s Strategic Vision Suba Chandran II THE RISE OF CHINA Dealing with a Rising Power: India-China Relations and the Reconstruction of Strategic Partnerships Alka Acharya The Prospect of China Up to 2020: A View from Japan Yasuhiro Matsuda The United States and a Rising China Derek Mitchell III NONPROLIFERATION Strengthening the Nonproliferation Regime in the Era of Nuclear Renaissance: A Common Agenda for Japan, the United States, and India Nobumasa Akiyama Global Nonproliferation Dynamics: An Indian Perspective Lawrence Prabhakar Nonproliferation Players and their Policies Jon Wolfstal IV ENERGY SECURITY Trends in Energy Security Mikkal Herberg 1 Japan ’s Energy Security Policy Manabu Miyagawa India’s Energy Security Chietigj Bajpaee V ECONOMIC CONVERGENCE A U.S. Perspective of Economic Convergence in East Asia Krishen Mehta New Open Regionalism? Current Trends and Perspectives in the Asia-Pacific Fukunari Kimura VI SOUTHEAST ASIA U.S. Perspectives on Southeast Asia: Opportunities for a Rethink Ben Dolven Southeast Asia: A New Regional Order Nobuto Yamamoto India’s Role in Southeast Asia: The Logic and Limits of Cooperation with the United States and Japan Sadanand Dhume VII COUNTER-TERRORISM Japan’s Counterterrorism Policy Naofumi Miyasaka Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and Japan: An Indian Perspective Manjeet Singh Pardesi VIII MARITIME -

SARS-Cov-2 Delayed Tokyo 2020 Olympics: Very Recent Advances in COVID-19 Detection, Treatment, and Vaccine Development Useful Conducting the Games in 2021

Advances in Infectious Diseases, 2020, 10, 56-66 https://www.scirp.org/journal/aid ISSN Online: 2164-2656 ISSN Print: 2164-2648 SARS-Cov-2 Delayed Tokyo 2020 Olympics: Very Recent Advances in COVID-19 Detection, Treatment, and Vaccine Development Useful Conducting the Games in 2021 Zameer Shervani1* , Intazam Khan2,3, Umair Yaqub Qazi4 1Nanomaterials Production Division, Food and Energy Security Research and Product Centre, Sendai, Japan 2Department of Neurology, North Shore University Hospital, New York, USA 3Department of Neurology and Neuroscience, Weill Cornell Medical, Cornell University, New York, USA 4Chemistry Department, College of Science, University of Hafar Al Batin, Hafar Al Batin, KSA How to cite this paper: Shervani, Z., Khan, Abstract I. and Qazi, U.Y. (2020) SARS-Cov-2 De- layed Tokyo 2020 Olympics: Very Recent The novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) delayed the Tokyo 2020 Games. The Advances in COVID-19 Detection, Treat- traveling by air, rail, road, and sea inside and outside the countries has stopped ment, and Vaccine Development Useful Con- to contain the virus. The amount of money lost and assistance needed to re- ducting the Games in 2021. Advances in Infectious Diseases, 10, 56-66. schedule and conduct the Games in 2021 have been estimated. With more https://doi.org/10.4236/aid.2020.103007 than one billion population is under the semi-locked down and movement of people is restricted, athletes cannot prepare at home and participate in the Received: June 5, 2020 Accepted: July 3, 2020 Games. The COVID-19 outbreak has spread around the world; it has already Published: July 6, 2020 infected 5.7 million people and caused 355,000 deaths reported on May 28, 2020 and the figures increasing every day. -

The Abduction of Japanese People by North Korea And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository THE ABDUCTION OF JAPANESE PEOPLE BY NORTH KOREA AND THE DYNAMICS OF JAPANESE DOMESTIC POLITICS AND FOREIGN POLICY: CASE STUDIES OF SHIN KANEMARU AND JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS IN 1990, 2002 AND 2004’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS by PARK Seohee 51114605 March 2017 Master’s Thesis / Independent Final Report Presented to Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Asia Pacific Studies ACKNOLEGEMENTS First and foremost, I praise and thank my Lord, who gives me the opportunity and talent to accomplish this research. You gave me the power to trust in my passion and pursue my dreams. I could never have done this without the faith I have in You, the Almighty. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Yoichiro Sato for your excellent support and guidance. You gave me the will to carry on and never give up in any hardship. Under your great supervision, this work came into existence. Again, I am so grateful for your trust, informative advice, and encouragement. I am deeply thankful and honored to my loving family. My two Mr. Parks and Mrs. Keum for your support, love and trust. Every moment of every day, I thank our Lord Almighty for giving me such a wonderful family. I would like to express my gratitude to Rotary Yoneyama Memorial Foundation, particularly to Mrs. Toshiko Takahashi (and her family), Kunisaki Club, Mr. Minoru Akiyoshi and Mr. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science Policy Networks in Japan: Case of the Automobile Air Pollution Policies Takashi Sagara A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy i UMI Number: U615939 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615939 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 "KSCSES p m r . rrti - S • - g r t W - • Declaration I, Takashi Sagara, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract The thesis seeks to examine whether the concept of the British policy network framework helps to explain policy change in Japan. For public policy studies in Japan, such an examination is significant because the framework has been rarely been used in analysis of Japanese policy. For public policy studies in Britain and elsewhere, such an examination would also bring benefits as it would help to answer the important question of whether it can be usefully applied in the other contexts. -

Ministério Tomada Das Relações Exteriores De Contas Anual

Ministério das Relações Exteriores MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES TOMADA DE CONTAS ANUAL EXERCÍCIO 2010 ESCRITÓRIO FINANCEIRO EM NOVA YORK a - Escritório Financeiro em Nova York b - Embaixada do Brasil em Tóquio c - Embaixada do Brasil em Londres d - Embaixada do Brasil em Pretória e - Embaixada do Brasil em Buenos Aires f - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Nova York g - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Buenos Aires h - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Miami i - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Tóquio j - Embaixada do Brasil em Santiago k - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Londres 1 - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Houston m - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Chicago n - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Boston o - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em São Francisco p - Embaixada do Brasil em Madrid q - Consulado-Geral do Brasil em Madrid VOLUME — II Para verificar as assinaturas, acesse www.tcu.gov.br/autenticidade, informando o código 46623911. MODELO DE ROL DE RESPONSÁVEIS UNIDADE GESTORA: 240034 GESTÃO 0001 NATUREZA DE RESPONSABILIDADE: (Artigo 10. Inciso I. Decisão Normativa 63/2010) Dirigente Máximo da Unidade/Ordenador de Despesas NOME CPF LUIZ AUGUSTO DE CASTRO 046.432.327-49 ENDEREÇO RESIDENCIAL CEP UF TELEFONE EX 5-32-2 Yoyogi Slxibuya-ku Tokyo 151-0053 (03) 3466-2255 ENDEREÇO DE CORREIO ELETRÔNICO [email protected] EMBAIXADOR DO BRASIL EM TÓQUIO CARGO OU FUNÇÃO NOMEAÇÃO A o/n° Data DOU 16/OUT/2008 DECRETO 16/JULJ2008 EXONERAÇÃO Ato/n" Data DOU 16/NOV/2010 PORTARIA I sauu2oio PERÍODO DE GESTÃO Data (início) Data (final) 01/JAN12010 15/NOV/2010 Dirigerite Máximo da Unidade Para verificar as assinaturas, acesse www.tcu.gov.br/autenticidade, informando o código 46623911. -

The Limits of Forgiveness in International Relations: Groups

JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations E-ISSN: 1647-7251 [email protected] Observatório de Relações Exteriores Portugal del Pilar Álvarez, María; del Mar Lunaklick, María; Muñoz, Tomás The limits of forgiveness in International Relations: Groups supporting the Yasukuni shrine in Japan and political tensions in East Asia JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations, vol. 7, núm. 2, noviembre, 2016, pp. 26- 49 Observatório de Relações Exteriores Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=413548516003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative OBSERVARE Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa e-ISSN: 1647-7251 Vol. 7, Nº. 2 (November 2016-April 2017), pp. 26-49 THE LIMITS OF FORGIVENESS IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: GROUPS SUPPORTING THE YASUKUNI SHRINE IN JAPAN AND POLITICAL TENSIONS IN EAST ASIA María del Pilar Álvarez [email protected] Research Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Salvador (USAL, Argentina) and Visiting Professor of the Department of International Studies at the University T. Di Tella (UTDT). Coordinator of the Research Group on East Asia of the Institute of Social Science Research (IDICSO) of the USAL. Postdoctoral Fellow of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) of Argentina. Doctor of Social Sciences from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA). Holder of a Master Degree on East Asia, Korea, from Yonsei University. Holder of a Degree in Political Science (UBA). -

Kobe University Repository : Kernel

Kobe University Repository : Kernel State Identity and Assistance Policy : Japan's Post- タイトル conflict Reconstruction Assistance in Afghanistan as Title 'Middle-power Diplomacy' 著者 Erkan, Kivilcim Author(s) 掲載誌・巻号・ページ Kobe University law review,47:87-107 Citation 刊行日 2013 Issue date 資源タイプ Departmental Bulletin Paper / 紀要論文 Resource Type 版区分 publisher Resource Version 権利 Rights DOI URL http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/handle_kernel/81005583 Create Date: 2017-12-17 State Identity and Assistance Policy: Japan’s Post-conflict Reconstruction Assistance in Afghanistan as ‘Middle-power Diplomacy’ Kivilcim ERKAN 2013 GRADUATE SCHOOL OF LAW, KOBE UNIVERSITY ROKKODAI, KOBE, JAPAN No.47 87 State Identity and Assistance Policy: Japan’s Post-conflict Reconstruction Assistance in Afghanistan as ‘Middle-power Diplomacy’ Kivilcim Erkan Abstract Most of the existing literature on Japan’s assistance policy1 is written from realist perspectives that emphasise interest-based and structural variables. While these approaches have provided useful insights, they remain insufficient for understanding some of the changes that have occurred in this policy sector since the 1990s. Such changes include the introduction of the human security norm, and increasing the humanitarian and post-conflict reconstruction assistance delivered by Japan. Japan’s contribution to the international efforts to eradicate terrorism in Afghanistan through post-conflict reconstruction assistance is a significant case that has received little scholarly attention in English-language literature. This paper is an attempt to fill that gap. By focusing on the policy-making process, the paper seeks to shed light on the questions of why and how Japan has become involved in the post-conflict reconstruction in Afghanistan in the aftermath of the United States–led coalition’s military intervention in 2001. -

Mike Mansfield Fellowships

The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation THE MIKE MANSFIELD FELLOWSHIPS ADVANCING UNDERSTANDING AND COOPERATION IN U.S.-JAPAN RELATIONS Washington, DC • Tokyo, Japan • Missoula, Montana • www.mansfieldfdn.org “...knowledge is essential for acceptance and understanding. By examining the political heritage, the economic experience and even the national myths that tie people together; by exploring the cultural, religious, and social forces that have molded a nation, we can begin to better understand each other and contribute to the knowledge and understanding that will strengthen our ties of friendship and lead to a better world.” —Mike Mansfield “…a vigorous program of exchanges is the surest way, over the long term, to build a true community of Asia Pacific nations.” —Mike Mansfield 1 The Mike Mansfield Fellowships “It has long been evident that the U.S.-Japan relationship has far-reaching consequences not only for the Pacific region but also for other parts of the world. In establishing the Mike Mansfield Fellowships, the U.S. Congress has taken an important step toward developing a new generation of government officials with a deeper understanding of Japan and close working relationships with Japanese officials. With the strong support of the government of Japan, the Mansfield Fellowship Program gives U.S. government officials a unique opportunity to learn about Japan and its government from the inside. We are pleased to see that U.S. agencies are making significant use of the Fellows who have completed the program, assigning them responsibility for Japan issues and cooperative programs and relying on their expertise and advice on how to work with Japan and foster close coordination on a wide range of issues. -

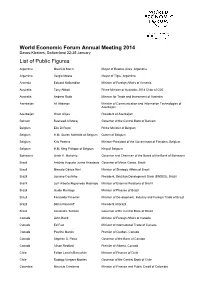

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Economic Sanctions by Japan Against North Korea: Consideration of the Legislation Process for FEFTCL (February 2004) and LSMCIPESS (June 2004)

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Economic Sanctions by Japan against North Korea: Consideration of the Legislation Process for FEFTCL (February 2004) and LSMCIPESS (June 2004) Satoru Miyamoto Abstract The Japanese government hardly imposed economic sanctions against North Korea when they launched a missile in August 1998. However, when North Korea launched missiles again in July 2006, the Japanese government began to impose strong economic sanctions because the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law (FEFTCL) and the Law for Special Measures Concerning Interdiction of Ports Entry by Specific Ships (LSMCIPESS) had been revised or enacted newly in 2004. It took six years since the suggestion of revising or enacting these two laws in 1998 to consummating them. Moreover, they are not cabinet-initiated legislation but lawmaker-initiated legislation. This paper explores the reasons why it took six years until the Diet members passed the bill given the relations between Japan and the United States, the relations between Japan and North Korea, and the relations between the Diet and the Cabinet in Japan. Key Words: economic sanctions, the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law, the Law for Special Measures Concerning Interdiction of Ports Entry by Specific Ships, Japan-North Korea relations, the Diet and the Cabinet relations Vol. 15, No. 2, 2006, pp. 21-46. Copyrightⓒ2006 by KINU 22 Economic Sanctions by Japan against North Korea Introduction In the immediate aftermath of the launch of seven missiles by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) on July 5, 2006, the Japanese government decided to impose economic sanctions that eventually prohibited port entry to the North Korean ship Man Gyong Bong 92. -

Outline of Duties, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan

Ministers, Senior Vice-Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries Ministers Prime Minister Chief Cabinet Secretary Shinzo ABE Yoshihide SUGA Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister of State for Disaster Management Akira AMAR I Keiji FURUYA Minister of State for the Nuclear Emergency Preparedness Minister of State for the Corporation in support of Compensation for Nuclear Damage Nobuteru ISHIHARA Toshimitsu MOTEGI Minister of State for Okinawa and Northern Territories Affairs Minister of State for National Strategic Special Zones Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy Minister of State for Decentralization Reform Minister of State for Space Policy Ichita YAMAMOTO Yoshitaka SHINDO Minister of State for Regulatory Reform Minister of State for Consumer Affairs and Food Safety Minister of State for Measures for Declining Birthrate Minister of State for Gender Equality Tomomi INADA Masako MORI i Senior Vice-Ministers Senior Vice-Minister Senior Vice-Minister Masazumi GOTODA Yasutoshi NISHIMURA Senior Vice-Minister Senior Vice-Minister Hiroshi OKADA Masakazu SEKIGUCHI Senior Vice-Minister Senior Vice-Minister Kazuyoshi AKABA Shinji INOUE Parliamentary Secretaries Parliamentary Secretary Parliamentary Secretary Yoshitami KAMEOKA Shinjiro KOIZUMI Parliamentary Secretary Parliamentary Secretary Takamaro FUKUOKA Fumiaki MATSUMOTO Parliamentary Secretary Parliamentary Secretary Tadahiko ITO Yoshihiko ISOZAKI Parliamentary Secretary Tomoko UKISHIMA *as of January 31, 2014 ii Contents ○Overview Office for the Public Interest -

Akbar, Jason 03-08-12

Institutional Reform in Japan: The Impact of Electoral, Governmental, and Administrative reforms on the Policymaking Process A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jason A. Akbar March 2012 © 2012 Jason A. Akbar. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Institutional Reform in Japan: The Impact of Electoral, Governmental, and Administrative reforms on the Policymaking Process by JASON A. AKBAR has been approved for the Department of Political Science and the College of Arts and Sciences by Takaaki Suzuki Associate Professor of Political Science Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract AKBAR, JASON A., M.A., March 2012, Political Science Institutional Reform in Japan: The Impact of Electoral, Governmental, and Administrative reforms on the Policymaking Process Director of Thesis: Takaaki Suzuki This thesis is a study of the institutional reforms in Japan, particularly the impact of electoral, governmental, and administrative reforms enacted during 1990s on the current policymaking structure and process. It is well documented that the LDP politicians, government bureaucrats and powerful special interest groups controlled the policymaking process prior to the reforms. Different Japan scholars have offered differing opinions on the impact of the 1994 electoral reform, 1999 Diet and government reform, and 2001 administrative reform on policymaking process. Here I have evaluated the impact of the 1990s reforms by examining three policymaking initiatives of the Koizumi administration. I suggest that understanding the impact of the 1990s reforms requires examining the specific details of each policy initiative at each stage of the policymaking process from creation to implementation.