Deming Rust M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS for EAST ASIA Toward

Contents Introduction I STRATEGIC VISIONS FOR EAST ASIA Toward Greater U.S.-Japan-India Strategic Dialogue and Coordination Mike Green Arc of Freedom and Prosperity Heigo Sato India’s Strategic Vision Suba Chandran II THE RISE OF CHINA Dealing with a Rising Power: India-China Relations and the Reconstruction of Strategic Partnerships Alka Acharya The Prospect of China Up to 2020: A View from Japan Yasuhiro Matsuda The United States and a Rising China Derek Mitchell III NONPROLIFERATION Strengthening the Nonproliferation Regime in the Era of Nuclear Renaissance: A Common Agenda for Japan, the United States, and India Nobumasa Akiyama Global Nonproliferation Dynamics: An Indian Perspective Lawrence Prabhakar Nonproliferation Players and their Policies Jon Wolfstal IV ENERGY SECURITY Trends in Energy Security Mikkal Herberg 1 Japan ’s Energy Security Policy Manabu Miyagawa India’s Energy Security Chietigj Bajpaee V ECONOMIC CONVERGENCE A U.S. Perspective of Economic Convergence in East Asia Krishen Mehta New Open Regionalism? Current Trends and Perspectives in the Asia-Pacific Fukunari Kimura VI SOUTHEAST ASIA U.S. Perspectives on Southeast Asia: Opportunities for a Rethink Ben Dolven Southeast Asia: A New Regional Order Nobuto Yamamoto India’s Role in Southeast Asia: The Logic and Limits of Cooperation with the United States and Japan Sadanand Dhume VII COUNTER-TERRORISM Japan’s Counterterrorism Policy Naofumi Miyasaka Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and Japan: An Indian Perspective Manjeet Singh Pardesi VIII MARITIME -

Sandspur, Vol. 32, No. 03, October 25, 1929

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-25-1929 Sandspur, Vol. 32, No. 03, October 25, 1929 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol. 32, No. 03, October 25, 1929" (1929). The Rollins Sandspur. 2619. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/2619 • THE ROLLINS SANDSPUR Published by Students of Rollins College Volume 32 WINTER PARK, FLORIDA, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25. 1929 Number 3 1 j Vi~~~nd --·i ADMINISTRATION I -I HAMILTON HOLT LITTLE THEATRE !SUBJECT CHOSEN I Reviews ANNOUNCES ART HONORS MEMORY PLANS PROGRAM FORINSTITUT EOF · -- BOARD MEMBERS OF E. E. SLOSSON STATESMANSHIP ½ I Coming Season Prom WillTING 11 .\LL . ises Brilliant En- Promment Leaders to Other Faculty Mem Propaganda Control is It pays to ndvertise. This col- Aid Art Develop tertainment umn received not one but two bers Also Pay Topic for Discussion books. ment Here Tribute at Second Institute The college office with rare 1 An unusually interm~ting selec thoughtfulness sent 11 Thc Future Six prominent leaders in nrt ! Ition of plays is being planned by of Party Govcnm1ent; Addresses and art education have accepted A former associate, an intimate Rollins players of the Little The- To what extent propaganda such and Discus~ions at the Institute of invitations to serve ns members friend, and a former instructor of atre \Vorkshop for the coming as that engineered by \Villiam B. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Rollins College: a Pictorial History

University of Central Florida STARS Text Materials of Central Florida Central Florida Memory 1-1-1980 Rollins College: A pictorial history Jack C. Lane Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-texts University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Central Florida Memory at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Materials of Central Florida by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lane, Jack C., "Rollins College: A pictorial history" (1980). Text Materials of Central Florida. 866. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-texts/866 —' --•--~—•—•—-—-- Rollins College: A Compiled and edited by Jack C. Lane Rollins College: A Pictorial History Rollins College: A Pictorial History/ Compiled and edited by Jack C. Lane. For the Rollins College Alumni, who made this book possible. Copyright © 1980 Rollins College Designed by Charles W. Hamilton Printed by Rose Printing Company, Inc. Tallahassee, Florida Parti 6 Founding a Liberal Arts College on the Southern Frontier Part II 52 Contents The Holt Era: Building a Liberal Arts College Part III 98 After Holt: Establishing Quality in an Era of Growth Part IV 145 Rollins: A Contemporary View Founding a Liberal Arts College on the Southern Frontier As with other 19th century liberal arts colleges, Rollins was founded as a result of several societal forces: educational denominationalism, the Ameri can churches' missionary zeal to found colleges; community boosterism, the belief of communities that colleges created instant prestige and guaranteed phenomenal growth; and real estate entrepreneurism, the desire of land developers to use colleges to promote their land schemes. -

1928 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 1917 SENATE L\1R

1928 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 1917 SENATE l\1r. HALE. I give notice that I shall move to take it up at the earliest possible moment; if not before, immediately follow TUESDAY, Januart; ~4, 19~8 ing the final disposition of the pending unfinished business, the merchant marine bill. (Legi-~:~latilve aa.y of Monilay, Ja;nuary ~3, 1928) Mr~ SIMMONS. Mr. President, in this connection I ask The Senate reassembled at 12 o"clock meridian, on the expira unanimous consent to have printed in the REcoRD an article tion of the recess. entitled u What is the truth about the S-4?" written by Mr. Mr. CURTIS. Mr. President, I suggest the absence of a Courtenay Terrett, a · newspaper correspondent who was pres quorum. ent all the while during the activities of the Government to Tbe VICE PRESIDENT. The clerk will eall the roll. recover the submarine and rescue its inmates. The article The legislative clerk called tbe roll, and the following Sena appears in the Outlook for January 11, 1928. I bad intended tors answered to their names : · to have it read to the Senate, but it is too long, so I am going .Ashurst Fess McKellar Shortridge to content myself by asking unanimous consent to have it Barkley Fletcher McMaster Simmons printed in the RECoRD. But I want to call the attention of Bayard Frazier McNary Smith Smoot Senators to the article, written by this newspaper man of ~Fagam ~~f~e ~:l~tfid Steck repute, I understand, as being worthy of their reading and Rlaine Gillett Moses Steiwer consideration. -

The Abduction of Japanese People by North Korea And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository THE ABDUCTION OF JAPANESE PEOPLE BY NORTH KOREA AND THE DYNAMICS OF JAPANESE DOMESTIC POLITICS AND FOREIGN POLICY: CASE STUDIES OF SHIN KANEMARU AND JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS IN 1990, 2002 AND 2004’S PYONGYANG SUMMIT MEETINGS by PARK Seohee 51114605 March 2017 Master’s Thesis / Independent Final Report Presented to Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Asia Pacific Studies ACKNOLEGEMENTS First and foremost, I praise and thank my Lord, who gives me the opportunity and talent to accomplish this research. You gave me the power to trust in my passion and pursue my dreams. I could never have done this without the faith I have in You, the Almighty. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Yoichiro Sato for your excellent support and guidance. You gave me the will to carry on and never give up in any hardship. Under your great supervision, this work came into existence. Again, I am so grateful for your trust, informative advice, and encouragement. I am deeply thankful and honored to my loving family. My two Mr. Parks and Mrs. Keum for your support, love and trust. Every moment of every day, I thank our Lord Almighty for giving me such a wonderful family. I would like to express my gratitude to Rotary Yoneyama Memorial Foundation, particularly to Mrs. Toshiko Takahashi (and her family), Kunisaki Club, Mr. Minoru Akiyoshi and Mr. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science Policy Networks in Japan: Case of the Automobile Air Pollution Policies Takashi Sagara A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy i UMI Number: U615939 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615939 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 "KSCSES p m r . rrti - S • - g r t W - • Declaration I, Takashi Sagara, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract The thesis seeks to examine whether the concept of the British policy network framework helps to explain policy change in Japan. For public policy studies in Japan, such an examination is significant because the framework has been rarely been used in analysis of Japanese policy. For public policy studies in Britain and elsewhere, such an examination would also bring benefits as it would help to answer the important question of whether it can be usefully applied in the other contexts. -

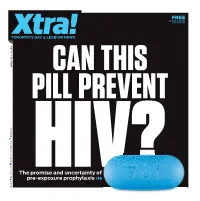

The Promise and Uncertainty of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

FREE 36,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS FEB 6–19, 2014 FEB 6–19, #764 CAN THIS PILL PREVENT @dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra HIV? The promise and uncertainty of dailyxtra.com pre-exposure prophylaxis E14 More at More 2 FEB 6–19, 2014 XTRA! TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS COMING SOON AT YONGE WITH DIRECT ACCESS TO WELLESLEY SUBWAY A series of illuminated boxes, carefully stacked. Spaces shifted gently left and right, geometry that draws the eye skyward. Totem, a building that’s poised to be iconic, is about great design and a location that fits you to a T. When you live here, you can go anywhere. Yonge Street, Yorkville, the Village, College Park, Yonge- Dundas Square, the Annex, University of Toronto and Ryerson are just steps away. IN FACT, TOTEM SCORES A PERFECT 100 ON WALKSCORE.COM! Plus, you’ve got sleek, modern suites, beautiful rooftop amenities and DIRECT ACCESS TO YOUR OWN SUBWAY ENTRANCE. THIS IS TOTEM. FROM THE MID $200’S SHIFT YOUR LIFESTYLE. get on it. REGISTER. totemcondos.com 416.792.1877 17 dundonald st. @ yonge street RENDERINGS ARE AN ARTIST’S IMPRESSION. SPECIFICATIONS ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. E.&O.E. EXCLUSIVE LISTING: BAKER REAL ESTATE INCORPORATED, BROKERAGE. BROKERS PROTECTED. MORE AT DAILYXTRA.COM XTRA! FEB 6–19, 2014 3 XTRA Published by Pink Triangle Press SHERBOURNE HEALTH CENTRE PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson 333 SHERBOURNE STREET TORONTO, ON M5A 2S5 EDITORIAL ADVERTISING MANAGING EDITOR Danny Glenwright ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling -

Canada's Opportunity in Energy Leadership

CANADA’S OPPORTUNITY IN ENERGY LEADERSHIP MIRED IN MISINFORMATION & MISUNDERSTANDINGS MAC VAN WIELINGEN | macvw.ca Fourth Quarter 2019 MAC VAN WIELINGEN FINANCIAL & ENERGY EXECUTIVE INVESTMENT MANAGER PHILANTHROPIST Past director of Founder of Speaker in 15 3 + Boards Companies Engagements /CE8CP9KGNKPIGPJCUDGGPECNNGFū%CNICT[ŨUEQTRQTCVGTCFKECNŬHQTJKURTQITGUUKXGVJKPMKPICPFWPKSWGITCURQHEQTRQTCVG NGCFGTUJKRUVTCVGI[CPFIQXGTPCPEG/CEŨUMPQYNGFIGCPFGZRGTVKUGKUVJGRTQFWEVQHQXGT[GCTUKPVJGHKPCPEKCNCPF GPGTI[UGEVQTU*GKUCHQWPFGT&KTGEVQT CPF2CTVPGT 2TGUGPV QH#4%(KPCPEKCN%QTR#4%(KPCPEKCNKUVJG NCTIGUVRTKXCVGGSWKV[KPXGUVOGPVOCPCIGOGPVEQORCP[KP%CPCFCHQEWUGFQPVJGGPGTI[UGEVQTYKVJCRRTQZKOCVGN[ DKNNKQPQHECRKVCNWPFGTOCPCIGOGPV*GLQKPGFVJGKPCWIWTCN$QCTFQH&KTGEVQTUQH#NDGTVC+PXGUVOGPV/CPCIGOGPV %QTRQTCVKQP #+/%Q KPCPFUGTXGFCU%JCKTHTQO#+/%QOCPCIGUQXGTDKNNKQPQPDGJCNHQH6JG 2TQXKPEGQH#NDGTVC/CEKUCNUQCHQWPFKPIRCTVPGTQHVJG%TGCVKXG&GUVTWEVKXG.CD4QEMKGU %&.4 C&KTGEVQTQHVJG +PUVKVWVGQH%QTRQTCVG&KTGEVQTU +%& CPFVJG8KEG%JCKTCPFHQWPFKPIOGODGTQHVJG$WUKPGUU%QWPEKNQH#NDGTVC $%# /CEKUCHQWPFGTCPFHQTOGT%JCKT QH#4%4GUQWTEGU.VFCNGCFKPI%CPCFKCPQKNCPFICUEQORCP[YKVJC EWTTGPVOCTMGVECRKVCNK\CVKQPQHCRRTQZKOCVGN[DKNNKQP+PCPFYJKNG/CEYCU%JCKTOCPQHVJG$QCTF#4% 4GUQWTEGUYCUTCPMGFKP$TGPFCP9QQF+PVGTPCVKQPCNŨU5JCTGJQNFGT%QPHKFGPEG+PFGZKPVJG'PGTI[CPF2QYGT)TQWR CPFYCUUGNGEVGFCUVJG6QR)WP$QCTFQHVJG;GCT#4%4GUQWTEGUTGOCKPUTGEQIPK\GFCUCVQR$QCTFTCPMKPICOQPIVJG VQRQHEQORCPKGUUWTXG[GFINQDCNN[D[$TGPFCP9QQF+PVGTPCVKQPCNKP +P/CEEQHQWPFGFVJG%CPCFKCP%GPVTGHQT#FXCPEGF.GCFGTUJKR %%#. CVVJG*CUMC[PG5EJQQNQH$WUKPGUUCVVJG -

"By Accident of Birth": the Battle Over Birthright Citizenship After United

“By Accident of Birth”: The Battle over Birthright Citizenship After United States v. Wong Kim Ark Amanda Frost In theory, birthright citizenship has been well established in U.S. law since 1898, when the Supreme Court held in United States v. Wong Kim Ark that all born on U.S. soil are U.S. citizens. The experience of immigrants and their families over the last 120 years tells a different story, however. This article draws on government records documenting the Wong family’s struggle for legal recognition to illuminate the convoluted history of birthright citizenship. Newly discovered archival materials reveal that Wong Kim Ark and his family experienced firsthand, and at times shaped, the fluctuating relationship between immigration, citizenship, and access to civil and political rights. The U.S. government reacted to its loss in Wong’s case at first by refusing to accept the rule of birthright citizenship, and then by creating onerous proof-of-citizenship requirements that obstructed recognition of birthright citizenship for certain ethnic groups. But the Wong family’s story is not only about the use and abuse of government power. Government records reveal that the Wongs, like others in their position, learned how to use the immigration bureaucracy to their own advantage, enabling them to establish a foothold in the United States despite the government’s efforts to bar them from doing so. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................39 I. AN IMMIGRANT FAMILY’S BACKSTORY ............................................43 Ann Loeb Bronfman Distinguished Professor of Law and Government, American University. I am grateful for the American Council of Learned Societies, which awarded me a fellowship to support the research and writing of this article. -

The Limits of Forgiveness in International Relations: Groups

JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations E-ISSN: 1647-7251 [email protected] Observatório de Relações Exteriores Portugal del Pilar Álvarez, María; del Mar Lunaklick, María; Muñoz, Tomás The limits of forgiveness in International Relations: Groups supporting the Yasukuni shrine in Japan and political tensions in East Asia JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations, vol. 7, núm. 2, noviembre, 2016, pp. 26- 49 Observatório de Relações Exteriores Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=413548516003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative OBSERVARE Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa e-ISSN: 1647-7251 Vol. 7, Nº. 2 (November 2016-April 2017), pp. 26-49 THE LIMITS OF FORGIVENESS IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: GROUPS SUPPORTING THE YASUKUNI SHRINE IN JAPAN AND POLITICAL TENSIONS IN EAST ASIA María del Pilar Álvarez [email protected] Research Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Salvador (USAL, Argentina) and Visiting Professor of the Department of International Studies at the University T. Di Tella (UTDT). Coordinator of the Research Group on East Asia of the Institute of Social Science Research (IDICSO) of the USAL. Postdoctoral Fellow of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) of Argentina. Doctor of Social Sciences from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA). Holder of a Master Degree on East Asia, Korea, from Yonsei University. Holder of a Degree in Political Science (UBA).