1 the Practice of Epidemiology a Meta-Regression Method For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic of Randomization Versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence

The new england journal of medicine Sounding Board The Magic of Randomization versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence Rory Collins, F.R.S., Louise Bowman, M.D., F.R.C.P., Martin Landray, Ph.D., F.R.C.P., and Richard Peto, F.R.S. Nonrandomized observational analyses of large safety and efficacy because the potential biases electronic patient databases are being promoted with respect to both can be appreciable. For ex- as an alternative to randomized clinical trials as ample, the treatment that is being assessed may a source of “real-world evidence” about the effi- well have been provided more or less often to cacy and safety of new and existing treatments.1-3 patients who had an increased or decreased risk For drugs or procedures that are already being of various health outcomes. Indeed, that is what used widely, such observational studies may in- would be expected in medical practice, since both volve exposure of large numbers of patients. the severity of the disease being treated and the Consequently, they have the potential to detect presence of other conditions may well affect the rare adverse effects that cannot plausibly be at- choice of treatment (often in ways that cannot be tributed to bias, generally because the relative reliably quantified). Even when associations of risk is large (e.g., Reye’s syndrome associated various health outcomes with a particular treat- with the use of aspirin, or rhabdomyolysis as- ment remain statistically significant after adjust- sociated with the use of statin therapy).4 Non- ment for all the known differences between pa- randomized clinical observation may also suf- tients who received it and those who did not fice to detect large beneficial effects when good receive it, these adjusted associations may still outcomes would not otherwise be expected (e.g., reflect residual confounding because of differ- control of diabetic ketoacidosis with insulin treat- ences in factors that were assessed only incom- ment, or the rapid shrinking of tumors with pletely or not at all (and therefore could not be chemotherapy). -

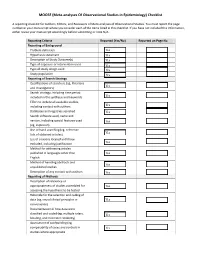

(Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist

MOOSE (Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist A reporting checklist for Authors, Editors, and Reviewers of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A. Reporting Criteria Reported (Yes/No) Reported on Page No. Reporting of Background Problem definition Hypothesis statement Description of Study Outcome(s) Type of exposure or intervention used Type of study design used Study population Reporting of Search Strategy Qualifications of searchers (eg, librarians and investigators) Search strategy, including time period included in the synthesis and keywords Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors Databases and registries searched Search software used, name and version, including special features used (eg, explosion) Use of hand searching (eg, reference lists of obtained articles) List of citations located and those excluded, including justification Method for addressing articles published in languages other than English Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies Description of any contact with authors Reporting of Methods Description of relevance or appropriateness of studies assembled for assessing the hypothesis to be tested Rationale for the selection and coding of data (eg, sound clinical principles or convenience) Documentation of how data were classified -

A Simple Censored Median Regression Estimator

Statistica Sinica 16(2006), 1043-1058 A SIMPLE CENSORED MEDIAN REGRESSION ESTIMATOR Lingzhi Zhou The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Abstract: Ying, Jung and Wei (1995) proposed an estimation procedure for the censored median regression model that regresses the median of the survival time, or its transform, on the covariates. The procedure requires solving complicated nonlinear equations and thus can be very difficult to implement in practice, es- pecially when there are multiple covariates. Moreover, the asymptotic covariance matrix of the estimator involves the density of the errors that cannot be esti- mated reliably. In this paper, we propose a new estimator for the censored median regression model. Our estimation procedure involves solving some convex min- imization problems and can be easily implemented through linear programming (Koenker and D'Orey (1987)). In addition, a resampling method is presented for estimating the covariance matrix of the new estimator. Numerical studies indi- cate the superiority of the finite sample performance of our estimator over that in Ying, Jung and Wei (1995). Key words and phrases: Censoring, convexity, LAD, resampling. 1. Introduction The accelerated failure time (AFT) model, which relates the logarithm of the survival time to covariates, is an attractive alternative to the popular Cox (1972) proportional hazards model due to its ease of interpretation. The model assumes that the failure time T , or some monotonic transformation of it, is linearly related to the covariate vector Z 0 Ti = β0Zi + "i; i = 1; : : : ; n: (1.1) Under censoring, we only observe Yi = min(Ti; Ci), where Ci are censoring times, and Ti and Ci are independent conditional on Zi. -

Cluster Analysis, a Powerful Tool for Data Analysis in Education

International Statistical Institute, 56th Session, 2007: Rita Vasconcelos, Mßrcia Baptista Cluster Analysis, a powerful tool for data analysis in Education Vasconcelos, Rita Universidade da Madeira, Department of Mathematics and Engeneering Caminho da Penteada 9000-390 Funchal, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] Baptista, Márcia Direcção Regional de Saúde Pública Rua das Pretas 9000 Funchal, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] 1. Introduction A database was created after an inquiry to 14-15 - year old students, which was developed with the purpose of identifying the factors that could socially and pedagogically frame the results in Mathematics. The data was collected in eight schools in Funchal (Madeira Island), and we performed a Cluster Analysis as a first multivariate statistical approach to this database. We also developed a logistic regression analysis, as the study was carried out as a contribution to explain the success/failure in Mathematics. As a final step, the responses of both statistical analysis were studied. 2. Cluster Analysis approach The questions that arise when we try to frame socially and pedagogically the results in Mathematics of 14-15 - year old students, are concerned with the types of decisive factors in those results. It is somehow underlying our objectives to classify the students according to the factors understood by us as being decisive in students’ results. This is exactly the aim of Cluster Analysis. The hierarchical solution that can be observed in the dendogram presented in the next page, suggests that we should consider the 3 following clusters, since the distances increase substantially after it: Variables in Cluster1: mother qualifications; father qualifications; student’s results in Mathematics as classified by the school teacher; student’s results in the exam of Mathematics; time spent studying. -

The Detection of Heteroscedasticity in Regression Models for Psychological Data

Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, Volume 58, 2016 (4), 567-592 The detection of heteroscedasticity in regression models for psychological data Andreas G. Klein1, Carla Gerhard2, Rebecca D. Büchner2, Stefan Diestel3 & Karin Schermelleh-Engel2 Abstract One assumption of multiple regression analysis is homoscedasticity of errors. Heteroscedasticity, as often found in psychological or behavioral data, may result from misspecification due to overlooked nonlinear predictor terms or to unobserved predictors not included in the model. Although methods exist to test for heteroscedasticity, they require a parametric model for specifying the structure of heteroscedasticity. The aim of this article is to propose a simple measure of heteroscedasticity, which does not need a parametric model and is able to detect omitted nonlinear terms. This measure utilizes the dispersion of the squared regression residuals. Simulation studies show that the measure performs satisfactorily with regard to Type I error rates and power when sample size and effect size are large enough. It outperforms the Breusch-Pagan test when a nonlinear term is omitted in the analysis model. We also demonstrate the performance of the measure using a data set from industrial psychology. Keywords: Heteroscedasticity, Monte Carlo study, regression, interaction effect, quadratic effect 1Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Prof. Dr. Andreas G. Klein, Department of Psychology, Goethe University Frankfurt, Theodor-W.-Adorno-Platz 6, 60629 Frankfurt; email: [email protected] 2Goethe University Frankfurt 3International School of Management Dortmund Leipniz-Research Centre for Working Environment and Human Factors 568 A. G. Klein, C. Gerhard, R. D. Büchner, S. Diestel & K. Schermelleh-Engel Introduction One of the standard assumptions underlying a linear model is that the errors are inde- pendently identically distributed (i.i.d.). -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) Courses EPBI 2219. Biostatistics and Public Health. 3 Credit Hours. This course is designed to provide students with a solid background in applied biostatistics in the field of public health. Specifically, the course includes an introduction to the application of biostatistics and a discussion of key statistical tests. Appropriate techniques to measure the extent of disease, the development of disease, and comparisons between groups in terms of the extent and development of disease are discussed. Techniques for summarizing data collected in samples are presented along with limited discussion of probability theory. Procedures for estimation and hypothesis testing are presented for means, for proportions, and for comparisons of means and proportions in two or more groups. Multivariable statistical methods are introduced but not covered extensively in this undergraduate course. Public Health majors, minors or students studying in the Public Health concentration must complete this course with a C or better. Level Registration Restrictions: May not be enrolled in one of the following Levels: Graduate. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. EPBI 2301. Public Health without Borders. 3 Credit Hours. Public Health without Borders is a course that will introduce you to the world of disease detectives to solve public health challenges in glocal (i.e., global and local) communities. You will learn about conducting disease investigations to support public health actions relevant to affected populations. You will discover what it takes to become a field epidemiologist through hands-on activities focused on promoting health and preventing disease in diverse populations across the globe. -

Testing Hypotheses for Differences Between Linear Regression Lines

United States Department of Testing Hypotheses for Differences Agriculture Between Linear Regression Lines Forest Service Stanley J. Zarnoch Southern Research Station e-Research Note SRS–17 May 2009 Abstract The general linear model (GLM) is often used to test for differences between means, as for example when the Five hypotheses are identified for testing differences between simple linear analysis of variance is used in data analysis for designed regression lines. The distinctions between these hypotheses are based on a priori assumptions and illustrated with full and reduced models. The studies. However, the GLM has a much wider application contrast approach is presented as an easy and complete method for testing and can also be used to compare regression lines. The for overall differences between the regressions and for making pairwise GLM allows for the use of both qualitative and quantitative comparisons. Use of the Bonferroni adjustment to ensure a desired predictor variables. Quantitative variables are continuous experimentwise type I error rate is emphasized. SAS software is used to illustrate application of these concepts to an artificial simulated dataset. The values such as diameter at breast height, tree height, SAS code is provided for each of the five hypotheses and for the contrasts age, or temperature. However, many predictor variables for the general test and all possible specific tests. in the natural resources field are qualitative. Examples of qualitative variables include tree class (dominant, Keywords: Contrasts, dummy variables, F-test, intercept, SAS, slope, test of conditional error. codominant); species (loblolly, slash, longleaf); and cover type (clearcut, shelterwood, seed tree). Fraedrich and others (1994) compared linear regressions of slash pine cone specific gravity and moisture content Introduction on collection date between families of slash pine grown in a seed orchard. -

5. Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance

Sociology 740 John Fox Lecture Notes 5. Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance Copyright © 2014 by John Fox Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 1 1. Introduction I One of the limitations of multiple-regression analysis is that it accommo- dates only quantitative explanatory variables. I Dummy-variable regressors can be used to incorporate qualitative explanatory variables into a linear model, substantially expanding the range of application of regression analysis. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 2 2. Goals: I To show how dummy regessors can be used to represent the categories of a qualitative explanatory variable in a regression model. I To introduce the concept of interaction between explanatory variables, and to show how interactions can be incorporated into a regression model by forming interaction regressors. I To introduce the principle of marginality, which serves as a guide to constructing and testing terms in complex linear models. I To show how incremental I -testsareemployedtotesttermsindummy regression models. I To show how analysis-of-variance models can be handled using dummy variables. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Dummy-Variable Regression and Analysis of Variance 3 3. A Dichotomous Explanatory Variable I The simplest case: one dichotomous and one quantitative explanatory variable. I Assumptions: Relationships are additive — the partial effect of each explanatory • variable is the same regardless of the specific value at which the other explanatory variable is held constant. The other assumptions of the regression model hold. • I The motivation for including a qualitative explanatory variable is the same as for including an additional quantitative explanatory variable: to account more fully for the response variable, by making the errors • smaller; and to avoid a biased assessment of the impact of an explanatory variable, • as a consequence of omitting another explanatory variables that is relatedtoit. -

Guidelines for Reporting Meta-Epidemiological Methodology Research

EBM Primer Evid Based Med: first published as 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 on 12 July 2017. Downloaded from Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research Mohammad Hassan Murad, Zhen Wang 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 Abstract The goal is generally broad but often focuses on exam- Published research should be reported to evidence users ining the impact of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the observed effect, describing the distribu- Evidence-Based Practice with clarity and transparency that facilitate optimal tion of research evidence in a specific setting, exam- Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, appraisal and use of evidence and allow replication Minnesota, USA by other researchers. Guidelines for such reporting ining heterogeneity and exploring its causes, identifying are available for several types of studies but not for and describing plausible biases and providing empirical meta-epidemiological methodology studies. Meta- evidence for hypothesised associations. Unlike classic Correspondence to: epidemiological studies adopt a systematic review epidemiology, the unit of analysis for meta-epidemio- Dr Mohammad Hassan Murad, or meta-analysis approach to examine the impact logical studies is a study, not a patient. The outcomes Evidence-based Practice Center, of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the of meta-epidemiological studies are usually not clinical Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street 6–8 observed effect and provide empirical evidence for outcomes. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA; hypothesised associations. The unit of analysis in meta- In this guide, we adapt the items used in the PRISMA murad. mohammad@ mayo. edu 9 epidemiological studies is a study, not a patient. The statement for reporting systematic reviews and outcomes of meta-epidemiological studies are usually meta-analysis to fit the setting of meta- epidemiological not clinical outcomes. -

Simple Linear Regression: Straight Line Regression Between an Outcome Variable (Y ) and a Single Explanatory Or Predictor Variable (X)

1 Introduction to Regression \Regression" is a generic term for statistical methods that attempt to fit a model to data, in order to quantify the relationship between the dependent (outcome) variable and the predictor (independent) variable(s). Assuming it fits the data reasonable well, the estimated model may then be used either to merely describe the relationship between the two groups of variables (explanatory), or to predict new values (prediction). There are many types of regression models, here are a few most common to epidemiology: Simple Linear Regression: Straight line regression between an outcome variable (Y ) and a single explanatory or predictor variable (X). E(Y ) = α + β × X Multiple Linear Regression: Same as Simple Linear Regression, but now with possibly multiple explanatory or predictor variables. E(Y ) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: A special case is polynomial regression. 2 3 E(Y ) = α + β1 × X + β2 × X + β3 × X + ::: Generalized Linear Model: Same as Multiple Linear Regression, but with a possibly transformed Y variable. This introduces considerable flexibil- ity, as non-linear and non-normal situations can be easily handled. G(E(Y )) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: In general, the transformation function G(Y ) can take any form, but a few forms are especially common: • Taking G(Y ) = logit(Y ) describes a logistic regression model: E(Y ) log( ) = α + β × X + β × X + β × X + ::: 1 − E(Y ) 1 1 2 2 3 3 2 • Taking G(Y ) = log(Y ) is also very common, leading to Poisson regression for count data, and other so called \log-linear" models. -

Chapter 2 Simple Linear Regression Analysis the Simple

Chapter 2 Simple Linear Regression Analysis The simple linear regression model We consider the modelling between the dependent and one independent variable. When there is only one independent variable in the linear regression model, the model is generally termed as a simple linear regression model. When there are more than one independent variables in the model, then the linear model is termed as the multiple linear regression model. The linear model Consider a simple linear regression model yX01 where y is termed as the dependent or study variable and X is termed as the independent or explanatory variable. The terms 0 and 1 are the parameters of the model. The parameter 0 is termed as an intercept term, and the parameter 1 is termed as the slope parameter. These parameters are usually called as regression coefficients. The unobservable error component accounts for the failure of data to lie on the straight line and represents the difference between the true and observed realization of y . There can be several reasons for such difference, e.g., the effect of all deleted variables in the model, variables may be qualitative, inherent randomness in the observations etc. We assume that is observed as independent and identically distributed random variable with mean zero and constant variance 2 . Later, we will additionally assume that is normally distributed. The independent variables are viewed as controlled by the experimenter, so it is considered as non-stochastic whereas y is viewed as a random variable with Ey()01 X and Var() y 2 . Sometimes X can also be a random variable.