Field Epidemiology Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Biostatistics

Introduction to Biostatistics Jie Yang, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Family, Population and Preventive Medicine Director Biostatistical Consulting Core Director Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource, Stony Brook Cancer Center In collaboration with Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC) and the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource (BB-SR), Stony Brook Cancer Center (SBCC). OUTLINE What is Biostatistics What does a biostatistician do • Experiment design, clinical trial design • Descriptive and Inferential analysis • Result interpretation What you should bring while consulting with a biostatistician WHAT IS BIOSTATISTICS • The science of (bio)statistics encompasses the design of biological/clinical experiments the collection, summarization, and analysis of data from those experiments the interpretation of, and inference from, the results How to Lie with Statistics (1954) by Darrell Huff. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PbODigCZqL8 GOAL OF STATISTICS Sampling POPULATION Probability SAMPLE Theory Descriptive Descriptive Statistics Statistics Inference Population Sample Parameters: Inferential Statistics Statistics: 흁, 흈, 흅… 푿ഥ , 풔, 풑ෝ,… PROPERTIES OF A “GOOD” SAMPLE • Adequate sample size (statistical power) • Random selection (representative) Sampling Techniques: 1.Simple random sampling 2.Stratified sampling 3.Systematic sampling 4.Cluster sampling 5.Convenience sampling STUDY DESIGN EXPERIEMENT DESIGN Completely Randomized Design (CRD) - Randomly assign the experiment units to the treatments -

Experimentation Science: a Process Approach for the Complete Design of an Experiment

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture 1996 - 8th Annual Conference Proceedings EXPERIMENTATION SCIENCE: A PROCESS APPROACH FOR THE COMPLETE DESIGN OF AN EXPERIMENT D. D. Kratzer K. A. Ash Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/agstatconference Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Applied Statistics Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kratzer, D. D. and Ash, K. A. (1996). "EXPERIMENTATION SCIENCE: A PROCESS APPROACH FOR THE COMPLETE DESIGN OF AN EXPERIMENT," Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2475-7772.1322 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture Kansas State University Applied Statistics in Agriculture 109 EXPERIMENTATION SCIENCE: A PROCESS APPROACH FOR THE COMPLETE DESIGN OF AN EXPERIMENT. D. D. Kratzer Ph.D., Pharmacia and Upjohn Inc., Kalamazoo MI, and K. A. Ash D.V.M., Ph.D., Town and Country Animal Hospital, Charlotte MI ABSTRACT Experimentation Science is introduced as a process through which the necessary steps of experimental design are all sufficiently addressed. Experimentation Science is defined as a nearly linear process of objective formulation, selection of experimentation unit and decision variable(s), deciding treatment, design and error structure, defining the randomization, statistical analyses and decision procedures, outlining quality control procedures for data collection, and finally analysis, presentation and interpretation of results. -

The Magic of Randomization Versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence

The new england journal of medicine Sounding Board The Magic of Randomization versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence Rory Collins, F.R.S., Louise Bowman, M.D., F.R.C.P., Martin Landray, Ph.D., F.R.C.P., and Richard Peto, F.R.S. Nonrandomized observational analyses of large safety and efficacy because the potential biases electronic patient databases are being promoted with respect to both can be appreciable. For ex- as an alternative to randomized clinical trials as ample, the treatment that is being assessed may a source of “real-world evidence” about the effi- well have been provided more or less often to cacy and safety of new and existing treatments.1-3 patients who had an increased or decreased risk For drugs or procedures that are already being of various health outcomes. Indeed, that is what used widely, such observational studies may in- would be expected in medical practice, since both volve exposure of large numbers of patients. the severity of the disease being treated and the Consequently, they have the potential to detect presence of other conditions may well affect the rare adverse effects that cannot plausibly be at- choice of treatment (often in ways that cannot be tributed to bias, generally because the relative reliably quantified). Even when associations of risk is large (e.g., Reye’s syndrome associated various health outcomes with a particular treat- with the use of aspirin, or rhabdomyolysis as- ment remain statistically significant after adjust- sociated with the use of statin therapy).4 Non- ment for all the known differences between pa- randomized clinical observation may also suf- tients who received it and those who did not fice to detect large beneficial effects when good receive it, these adjusted associations may still outcomes would not otherwise be expected (e.g., reflect residual confounding because of differ- control of diabetic ketoacidosis with insulin treat- ences in factors that were assessed only incom- ment, or the rapid shrinking of tumors with pletely or not at all (and therefore could not be chemotherapy). -

Globalization and Infectious Diseases: a Review of the Linkages

TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 SPECIAL TOPICS NO.3 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) The "Special Topics in Social, Economic and Behavioural (SEB) Research" series are peer-reviewed publications commissioned by the TDR Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research. For further information please contact: Dr Johannes Sommerfeld Manager Steering Committee for Social, Economic and Behavioural Research (SEB) UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) World Health Organization 20, Avenue Appia CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages Lance Saker,1 MSc MRCP Kelley Lee,1 MPA, MA, D.Phil. Barbara Cannito,1 MSc Anna Gilmore,2 MBBS, DTM&H, MSc, MFPHM Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum,1 D.Phil. 1 Centre on Global Change and Health London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK 2 European Centre on Health of Societies in Transition (ECOHOST) London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK TDR/STR/SEB/ST/04.2 Copyright © World Health Organization on behalf of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases 2004 All rights reserved. The use of content from this health information product for all non-commercial education, training and information purposes is encouraged, including translation, quotation and reproduction, in any medium, but the content must not be changed and full acknowledgement of the source must be clearly stated. -

On Confinement and Quarantine Concerns on an SEIAR Epidemic

S S symmetry Article On Confinement and Quarantine Concerns on an SEIAR Epidemic Model with Simulated Parameterizations for the COVID-19 Pandemic Manuel De la Sen 1,* , Asier Ibeas 2 and Ravi P. Agarwal 3 1 Campus of Leioa, Institute of Research and Development of Processes IIDP, University of the Basque Country, 48940 Leioa (Bizkaia), Spain 2 Department of Telecommunications and Systems Engineering, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, UAB, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Mathematics, Texas A & M University, 700 Univ Blvd, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 September 2020; Accepted: 30 September 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: This paper firstly studies an SIR (susceptible-infectious-recovered) epidemic model without demography and with no disease mortality under both total and under partial quarantine of the susceptible subpopulation or of both the susceptible and the infectious ones in order to satisfy the hospital availability requirements on bed disposal and other necessary treatment means for the seriously infectious subpopulations. The seriously infectious individuals are assumed to be a part of the total infectious being described by a time-varying proportional function. A time-varying upper-bound of those seriously infected individuals has to be satisfied as objective by either a total confinement or partial quarantine intervention of the susceptible subpopulation. Afterwards, a new extended SEIR (susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered) epidemic model, which is referred to as an SEIAR (susceptible-exposed-symptomatic infectious-asymptomatic infectious-recovered) epidemic model with demography and disease mortality is given and focused on so as to extend the above developed ideas on the SIR model. -

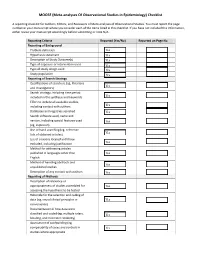

(Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist

MOOSE (Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist A reporting checklist for Authors, Editors, and Reviewers of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A. Reporting Criteria Reported (Yes/No) Reported on Page No. Reporting of Background Problem definition Hypothesis statement Description of Study Outcome(s) Type of exposure or intervention used Type of study design used Study population Reporting of Search Strategy Qualifications of searchers (eg, librarians and investigators) Search strategy, including time period included in the synthesis and keywords Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors Databases and registries searched Search software used, name and version, including special features used (eg, explosion) Use of hand searching (eg, reference lists of obtained articles) List of citations located and those excluded, including justification Method for addressing articles published in languages other than English Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies Description of any contact with authors Reporting of Methods Description of relevance or appropriateness of studies assembled for assessing the hypothesis to be tested Rationale for the selection and coding of data (eg, sound clinical principles or convenience) Documentation of how data were classified -

MMWR Early and Were Reported to Two Respective Local Health Jurisdictions, Release on the MMWR Website (

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice — Skagit County, Washington, March 2020 Lea Hamner, MPH1; Polly Dubbel, MPH1; Ian Capron1; Andy Ross, MPH1; Amber Jordan, MPH1; Jaxon Lee, MPH1; Joanne Lynn1; Amelia Ball1; Simranjit Narwal, MSc1; Sam Russell1; Dale Patrick1; Howard Leibrand, MD1 On May 12, 2020, this report was posted as an MMWR Early and were reported to two respective local health jurisdictions, Release on the MMWR website (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr). without indication of a common source of exposure. On On March 17, 2020, a member of a Skagit County, March 17, the choir director sent a second e-mail stating that Washington, choir informed Skagit County Public Health 24 members reported that they had developed influenza-like (SCPH) that several members of the 122-member choir had symptoms since March 11, and at least one had received test become ill. Three persons, two from Skagit County and one results positive for SARS-CoV-2. The email emphasized the from another area, had test results positive for SARS-CoV-2, importance of social distancing and awareness of symptoms the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). suggestive of COVID-19. These two emails led many members Another 25 persons had compatible symptoms. SCPH to self-isolate or quarantine before a delegated member of the obtained the choir’s member list and began an investigation on choir notified SCPH on March 17. March 18. Among 61 persons who attended a March 10 choir All 122 members were interviewed by telephone either practice at which one person was known to be symptomatic, during initial investigation of the cluster (March 18–20; 53 cases were identified, including 33 confirmed and 20 115 members) or a follow-up interview (April 7–10; 117); most probable cases (secondary attack rates of 53.3% among con- persons participated in both interviews. -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) Courses EPBI 2219. Biostatistics and Public Health. 3 Credit Hours. This course is designed to provide students with a solid background in applied biostatistics in the field of public health. Specifically, the course includes an introduction to the application of biostatistics and a discussion of key statistical tests. Appropriate techniques to measure the extent of disease, the development of disease, and comparisons between groups in terms of the extent and development of disease are discussed. Techniques for summarizing data collected in samples are presented along with limited discussion of probability theory. Procedures for estimation and hypothesis testing are presented for means, for proportions, and for comparisons of means and proportions in two or more groups. Multivariable statistical methods are introduced but not covered extensively in this undergraduate course. Public Health majors, minors or students studying in the Public Health concentration must complete this course with a C or better. Level Registration Restrictions: May not be enrolled in one of the following Levels: Graduate. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. EPBI 2301. Public Health without Borders. 3 Credit Hours. Public Health without Borders is a course that will introduce you to the world of disease detectives to solve public health challenges in glocal (i.e., global and local) communities. You will learn about conducting disease investigations to support public health actions relevant to affected populations. You will discover what it takes to become a field epidemiologist through hands-on activities focused on promoting health and preventing disease in diverse populations across the globe. -

Optimal Vaccine Subsidies for Endemic and Epidemic Diseases Matthew Goodkin-Gold, Michael Kremer, Christopher M

WORKING PAPER · NO. 2020-162 Optimal Vaccine Subsidies for Endemic and Epidemic Diseases Matthew Goodkin-Gold, Michael Kremer, Christopher M. Snyder, and Heidi L. Williams NOVEMBER 2020 5757 S. University Ave. Chicago, IL 60637 Main: 773.702.5599 bfi.uchicago.edu OPTIMAL VACCINE SUBSIDIES FOR ENDEMIC AND EPIDEMIC DISEASES Matthew Goodkin-Gold Michael Kremer Christopher M. Snyder Heidi L. Williams The authors are grateful for helpful comments from Witold Więcek and seminar participants in the Harvard Economics Department, Yale School of Medicine, the “Infectious Diseases in Poor Countries and the Social Sciences” conference at Cornell University, the DIMACS “Game Theoretic Approaches to Epidemiology and Ecology” workshop at Rutgers University, the “Economics of the Pharmaceutical Industry” roundtable at the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Economics, the U.S. National Institutes of Health “Models of Infectious Disease Agent” study group at the Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, the American Economic Association “Economics of Infectious Disease” session, and the Health and Pandemics (HELP!) Economics Working Group “Covid-19 and Vaccines” workshop. Maya Durvasula, Nishi Jain, Amrita Misha, Frank Schilbach, and Alfian Tjandra provided excellent research assistance. Williams gratefully acknowledges financial support from NIA grant number T32- AG000186 to the NBER. © 2020 by Matthew Goodkin-Gold, Michael Kremer, Christopher M. Snyder, and Heidi L. Williams. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Optimal Vaccine Subsidies for Endemic and Epidemic Diseases Matthew Goodkin-Gold, Michael Kremer, Christopher M. Snyder, and Heidi L. -

A New Twenty-First Century Science for Effective Epidemic Response

Review A new twenty-first century science for effective epidemic response https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1717-y Juliet Bedford1, Jeremy Farrar2*, Chikwe Ihekweazu3, Gagandeep Kang4, Marion Koopmans5 & John Nkengasong6 Received: 10 June 2019 Accepted: 24 September 2019 With rapidly changing ecology, urbanization, climate change, increased travel and Published online: 6 November 2019 fragile public health systems, epidemics will become more frequent, more complex and harder to prevent and contain. Here we argue that our concept of epidemics must evolve from crisis response during discrete outbreaks to an integrated cycle of preparation, response and recovery. This is an opportunity to combine knowledge and skills from all over the world—especially at-risk and afected communities. Many disciplines need to be integrated, including not only epidemiology but also social sciences, research and development, diplomacy, logistics and crisis management. This requires a new approach to training tomorrow’s leaders in epidemic prevention and response. connected, high-density urban areas (particularly relevant to Ebola, Anniversary dengue, influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coro- collection: navirus SARS-CoV). These factors and effects combine and interact, go.nature.com/ fuelling more-complex epidemics. nature150 Although rare compared to those diseases that cause the majority of the burden on population health, the nature of such epidemics disrupts health systems, amplifies mistrust among communities and creates high and long-lasting socioeconomic effects, especially in low- and When Nature published its first issue in 18691, a new understanding of middle-income countries. Their increasing frequency demands atten- infectious diseases was taking shape. The work of William Farr2, Ignaz tion. -

Understanding Replication of Experiments in Software Engineering: a Classification Omar S

Understanding replication of experiments in software engineering: A classification Omar S. Gómez a, , Natalia Juristo b,c, Sira Vegas b a Facultad de Matemáticas, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, 97119 Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico Facultad de Informática, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 28660 Boadilla del Monte, Madrid, Spain c Department of Information Processing Science, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland abstract Context: Replication plays an important role in experimental disciplines. There are still many uncertain-ties about how to proceed with replications of SE experiments. Should replicators reuse the baseline experiment materials? How much liaison should there be among the original and replicating experiment-ers, if any? What elements of the experimental configuration can be changed for the experiment to be considered a replication rather than a new experiment? Objective: To improve our understanding of SE experiment replication, in this work we propose a classi-fication which is intend to provide experimenters with guidance about what types of replication they can perform. Method: The research approach followed is structured according to the following activities: (1) a litera-ture review of experiment replication in SE and in other disciplines, (2) identification of typical elements that compose an experimental configuration, (3) identification of different replications purposes and (4) development of a classification of experiment replications for SE. Results: We propose a classification of replications which provides experimenters in SE with guidance about what changes can they make in a replication and, based on these, what verification purposes such a replication can serve. The proposed classification helped to accommodate opposing views within a broader framework, it is capable of accounting for less similar replications to more similar ones regarding the baseline experiment.