The Magic of Randomization Versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

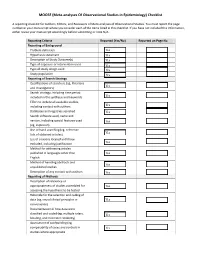

(Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist

MOOSE (Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist A reporting checklist for Authors, Editors, and Reviewers of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A. Reporting Criteria Reported (Yes/No) Reported on Page No. Reporting of Background Problem definition Hypothesis statement Description of Study Outcome(s) Type of exposure or intervention used Type of study design used Study population Reporting of Search Strategy Qualifications of searchers (eg, librarians and investigators) Search strategy, including time period included in the synthesis and keywords Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors Databases and registries searched Search software used, name and version, including special features used (eg, explosion) Use of hand searching (eg, reference lists of obtained articles) List of citations located and those excluded, including justification Method for addressing articles published in languages other than English Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies Description of any contact with authors Reporting of Methods Description of relevance or appropriateness of studies assembled for assessing the hypothesis to be tested Rationale for the selection and coding of data (eg, sound clinical principles or convenience) Documentation of how data were classified -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) Courses EPBI 2219. Biostatistics and Public Health. 3 Credit Hours. This course is designed to provide students with a solid background in applied biostatistics in the field of public health. Specifically, the course includes an introduction to the application of biostatistics and a discussion of key statistical tests. Appropriate techniques to measure the extent of disease, the development of disease, and comparisons between groups in terms of the extent and development of disease are discussed. Techniques for summarizing data collected in samples are presented along with limited discussion of probability theory. Procedures for estimation and hypothesis testing are presented for means, for proportions, and for comparisons of means and proportions in two or more groups. Multivariable statistical methods are introduced but not covered extensively in this undergraduate course. Public Health majors, minors or students studying in the Public Health concentration must complete this course with a C or better. Level Registration Restrictions: May not be enrolled in one of the following Levels: Graduate. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. EPBI 2301. Public Health without Borders. 3 Credit Hours. Public Health without Borders is a course that will introduce you to the world of disease detectives to solve public health challenges in glocal (i.e., global and local) communities. You will learn about conducting disease investigations to support public health actions relevant to affected populations. You will discover what it takes to become a field epidemiologist through hands-on activities focused on promoting health and preventing disease in diverse populations across the globe. -

Guidelines for Reporting Meta-Epidemiological Methodology Research

EBM Primer Evid Based Med: first published as 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 on 12 July 2017. Downloaded from Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research Mohammad Hassan Murad, Zhen Wang 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 Abstract The goal is generally broad but often focuses on exam- Published research should be reported to evidence users ining the impact of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the observed effect, describing the distribu- Evidence-Based Practice with clarity and transparency that facilitate optimal tion of research evidence in a specific setting, exam- Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, appraisal and use of evidence and allow replication Minnesota, USA by other researchers. Guidelines for such reporting ining heterogeneity and exploring its causes, identifying are available for several types of studies but not for and describing plausible biases and providing empirical meta-epidemiological methodology studies. Meta- evidence for hypothesised associations. Unlike classic Correspondence to: epidemiological studies adopt a systematic review epidemiology, the unit of analysis for meta-epidemio- Dr Mohammad Hassan Murad, or meta-analysis approach to examine the impact logical studies is a study, not a patient. The outcomes Evidence-based Practice Center, of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the of meta-epidemiological studies are usually not clinical Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street 6–8 observed effect and provide empirical evidence for outcomes. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA; hypothesised associations. The unit of analysis in meta- In this guide, we adapt the items used in the PRISMA murad. mohammad@ mayo. edu 9 epidemiological studies is a study, not a patient. The statement for reporting systematic reviews and outcomes of meta-epidemiological studies are usually meta-analysis to fit the setting of meta- epidemiological not clinical outcomes. -

Simple Linear Regression: Straight Line Regression Between an Outcome Variable (Y ) and a Single Explanatory Or Predictor Variable (X)

1 Introduction to Regression \Regression" is a generic term for statistical methods that attempt to fit a model to data, in order to quantify the relationship between the dependent (outcome) variable and the predictor (independent) variable(s). Assuming it fits the data reasonable well, the estimated model may then be used either to merely describe the relationship between the two groups of variables (explanatory), or to predict new values (prediction). There are many types of regression models, here are a few most common to epidemiology: Simple Linear Regression: Straight line regression between an outcome variable (Y ) and a single explanatory or predictor variable (X). E(Y ) = α + β × X Multiple Linear Regression: Same as Simple Linear Regression, but now with possibly multiple explanatory or predictor variables. E(Y ) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: A special case is polynomial regression. 2 3 E(Y ) = α + β1 × X + β2 × X + β3 × X + ::: Generalized Linear Model: Same as Multiple Linear Regression, but with a possibly transformed Y variable. This introduces considerable flexibil- ity, as non-linear and non-normal situations can be easily handled. G(E(Y )) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: In general, the transformation function G(Y ) can take any form, but a few forms are especially common: • Taking G(Y ) = logit(Y ) describes a logistic regression model: E(Y ) log( ) = α + β × X + β × X + β × X + ::: 1 − E(Y ) 1 1 2 2 3 3 2 • Taking G(Y ) = log(Y ) is also very common, leading to Poisson regression for count data, and other so called \log-linear" models. -

A Systematic Review of Quasi-Experimental Study Designs in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance

INVITED ARTICLE ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE George M. Eliopoulos, Section Editor A Systematic Review of Quasi-Experimental Study Designs in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance Anthony D. Harris,1,2 Ebbing Lautenbach,3,4 and Eli Perencevich1,2 1 2 Division of Health Care Outcomes Research, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Veterans Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/41/1/77/325424 by guest on 24 September 2021 Affairs Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland; and 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, and 4Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania We performed a systematic review of articles published during a 2-year period in 4 journals in the field of infectious diseases to determine the extent to which the quasi-experimental study design is used to evaluate infection control and antibiotic resistance. We evaluated studies on the basis of the following criteria: type of quasi-experimental study design used, justification of the use of the design, use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and recognition of potential limitations of the design. A total of 73 articles featured a quasi-experimental study design. Twelve (16%) were associated with a quasi-exper- imental design involving a control group. Three (4%) provided justification for the use of the quasi-experimental study design. Sixteen (22%) used correct nomenclature to describe the study. Seventeen (23%) mentioned at least 1 of the potential limitations of the use of a quasi-experimental study design. -

Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE)

CONSENSUS STATEMENT Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology A Proposal for Reporting Donna F. Stroup, PhD, MSc Objective Because of the pressure for timely, informed decisions in public health and Jesse A. Berlin, ScD clinical practice and the explosion of information in the scientific literature, research Sally C. Morton, PhD results must be synthesized. Meta-analyses are increasingly used to address this prob- lem, and they often evaluate observational studies. A workshop was held in Atlanta, Ingram Olkin, PhD Ga, in April 1997, to examine the reporting of meta-analyses of observational studies G. David Williamson, PhD and to make recommendations to aid authors, reviewers, editors, and readers. Drummond Rennie, MD Participants Twenty-seven participants were selected by a steering committee, based on expertise in clinical practice, trials, statistics, epidemiology, social sciences, and biomedi- David Moher, MSc cal editing. Deliberations of the workshop were open to other interested scientists. Fund- Betsy J. Becker, PhD ing for this activity was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Theresa Ann Sipe, PhD Evidence We conducted a systematic review of the published literature on the con- duct and reporting of meta-analyses in observational studies using MEDLINE, Educa- Stephen B. Thacker, MD, MSc tional Research Information Center (ERIC), PsycLIT, and the Current Index to Statistics. for the Meta-analysis Of We also examined reference lists of the 32 studies retrieved and contacted experts in Observational Studies in the field. Participants were assigned to small-group discussions on the subjects of bias, Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group searching and abstracting, heterogeneity, study categorization, and statistical methods. -

Epidemiology and Statistics for the Ophthalmologist

This book will give ophthalmologists a simple, clear presentation of epidemiologic and statistical techniques relevant to conducting, inter preting, and assimilating the commonest types of clinical research. Such information has become all the more important as clinical ophthalmic research has shifted from anecdotal reports and un critical presentations of patient data to carefully controlled and organized studies. The text is divided into two parts. The first part deals with epi demiologic concepts and their application and with the various types of studies (for example, prospective or longitudinal) and their organization (use of controls, randomness, sources of bias, choice of sample size, standardization and reproducibility). The second half of the text is devoted to the selection and use of the relevant sta tistical manipulations: determining sample size and testing the sta tistical significance of results. The text is illustrated with many examples covering topics such as blindness registry data, incidence of visual field loss with different levels of ocular hypertension, sensi tivity and specificity of tests for glaucoma, and sampling bias in studies of the safety of intraocular lenses. References and several helpful appendices are included. The Author Alfred Sommer received his M.D. in Ophthalmology from Harvard University Medical School, and his M.H. Sc. degree in Epidemiology from Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. At the Wilmer Institute, he is the Director of the International Center for Epidemiologic and Preventive Ophthalmology. He is the author of Field Guide to the Detection and Control of Xerophthalmia. Oxford University Press, N ew York Cover design by Joy Taylor ISBN O-19-502656-X Epidemiology and Statistics for the Ophthalmologist ALFRED SOMMER, M.D., M.R.Se. -

Rocreg — Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Regression

Title stata.com rocreg — Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) regression Description Quick start Menu Syntax Options Remarks and examples Stored results Methods and formulas Acknowledgments References Also see Description The rocreg command is used to perform receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses with rating and discrete classification data under the presence of covariates. The two variables refvar and classvar must be numeric. The reference variable indicates the true state of the observation—such as diseased and nondiseased or normal and abnormal—and must be coded as 0 and 1. The refvar coded as 0 can also be called the control population, while the refvar coded as 1 comprises the case population. The rating or outcome of the diagnostic test or test modality is recorded in classvar, which must be ordinal, with higher values indicating higher risk. rocreg can fit three models: a nonparametric model, a parametric probit model that uses the bootstrap for inference, and a parametric probit model fit using maximum likelihood. Quick start Nonparametric estimation with bootstrap resampling Area under the ROC curve for test classifier v1 and true state true using seed 20547 rocreg true v1, bseed(20547) Add v2 as an additional classifier rocreg true v1 v2, bseed(20547) As above, but estimate ROC value for a false-positive rate of 0.7 rocreg true v1 v2, bseed(20547) roc(.7) Covariate stratification of controls by categorical variable a using seed 121819 rocreg true v1 v2, bseed(121819) ctrlcov(a) Linear control covariate adjustment with -

7 Epidemiology: a Tool for the Assessment of Risk

7 Epidemiology: a tool for the assessment of risk Ursula J. Blumenthal, Jay M. Fleisher, Steve A. Esrey and Anne Peasey The purpose of this chapter is to introduce and demonstrate the use of a key tool for the assessment of risk. The word epidemiology is derived from Greek and its literal interpretation is ‘studies upon people’. A more usual definition, however, is the scientific study of disease patterns among populations in time and space. This chapter introduces some of the techniques used in epidemiological studies and illustrates their uses in the evaluation or setting of microbiological guidelines for recreational water, wastewater reuse and drinking water. 7.1 INTRODUCTION Modern epidemiological techniques developed largely as a result of outbreak investigations of infectious disease during the nineteenth century. © 2001 World Health Organization (WHO). Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards and Health. Edited by Lorna Fewtrell and Jamie Bartram. Published by IWA Publishing, London, UK. ISBN: 1 900222 28 0 136 Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards and Health Environmental epidemiology, however, has a long history dating back to Roman and Greek times when early physicians perceived links between certain environmental features and ill health. John Snow’s study of cholera in London and its relationship to water supply (Snow 1855) is widely considered to be the first epidemiological study (Baker et al. 1999). Mapping cases of cholera, Snow was able to establish that cases of illness were clustered in the streets close to the Broad Street pump, with comparatively few cases occurring in the vicinity of other local pumps. Epidemiological investigations can provide strong evidence linking exposure to the incidence of infection or disease in a population. -

Study Designs and Their Outcomes

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC CHAPTERNOT FOR SALE 3 OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © JonesStudy & Bartlett Designs Learning, LLC and Their Outcomes© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION “Natural selection is a mechanism for generating an exceedingly high degree of improbability.” —Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher Peter Wludyka © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION OBJECTIVES ______________________________________________________________________________ • Define research design, research study, and research protocol. • Identify the major features of a research study. • Identify© Jonesthe four types& Bartlett of designs Learning,discussed in this LLC chapter. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC • DescribeNOT nonexperimental FOR SALE designs, OR DISTRIBUTIONincluding cohort, case-control, and cross-sectionalNOT studies. FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION • Describe the types of epidemiological parameters that can be estimated with exposed cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies along with the role, appropriateness, and interpreta- tion of relative risk and odds ratios in the context of design choice. • Define true experimental design and describe its role in assessing cause-and-effect relation- © Jones &ships Bartlett along with Learning, definitions LLCof and discussion of the role of ©internal Jones and &external Bartlett validity Learning, in LLC NOT FOR evaluatingSALE OR designs. DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION • Describe commonly used experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), after-only (post-test only) designs, the Solomon four-group design, crossover designs, and factorial designs. -

Role of Epidemiology and Statistics in Advanced Nursing Practice

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC CHAPTERNOT FOR SALE 2 OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © JonesRole & Bartlett of Learning, Epidemiology LLC and ©Statistics Jones & Bartlett in Learning, LLC NOT FORAdvanced SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Nursing PracticeNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION “Chance favors prepared minds.” —Louis Pasteur © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONPeter Wludyka NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION OBJECTIVES ______________________________________________________________________________ • After© completing Jones this& Bartlett chapter the Learning, reader will understand LLC that statistical methods© and Jones ideas as & Bartlett Learning, LLC well NOTas practical FOR probability SALE areOR essential DISTRIBUTION to understanding epidemiology and itsNOT role inFOR ad- SALE OR DISTRIBUTION vanced nursing practice. • The overall objective of the chapter is to familiarize the reader with the key elements of statis- tics (and statistical inference) including the role of level of measurement; methods for present- ing, summarizing, and analyzing interval or categorical data; estimation; hypothesis testing; © Jones &and Bartlett modeling. Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR• TheSALE key epidemiologicalOR DISTRIBUTION ideas of incidence and prevalence NOTare defined, FOR the SALE distinction OR beDISTRIBUTION-