Guidelines for Reporting Meta-Epidemiological Methodology Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic of Randomization Versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence

The new england journal of medicine Sounding Board The Magic of Randomization versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence Rory Collins, F.R.S., Louise Bowman, M.D., F.R.C.P., Martin Landray, Ph.D., F.R.C.P., and Richard Peto, F.R.S. Nonrandomized observational analyses of large safety and efficacy because the potential biases electronic patient databases are being promoted with respect to both can be appreciable. For ex- as an alternative to randomized clinical trials as ample, the treatment that is being assessed may a source of “real-world evidence” about the effi- well have been provided more or less often to cacy and safety of new and existing treatments.1-3 patients who had an increased or decreased risk For drugs or procedures that are already being of various health outcomes. Indeed, that is what used widely, such observational studies may in- would be expected in medical practice, since both volve exposure of large numbers of patients. the severity of the disease being treated and the Consequently, they have the potential to detect presence of other conditions may well affect the rare adverse effects that cannot plausibly be at- choice of treatment (often in ways that cannot be tributed to bias, generally because the relative reliably quantified). Even when associations of risk is large (e.g., Reye’s syndrome associated various health outcomes with a particular treat- with the use of aspirin, or rhabdomyolysis as- ment remain statistically significant after adjust- sociated with the use of statin therapy).4 Non- ment for all the known differences between pa- randomized clinical observation may also suf- tients who received it and those who did not fice to detect large beneficial effects when good receive it, these adjusted associations may still outcomes would not otherwise be expected (e.g., reflect residual confounding because of differ- control of diabetic ketoacidosis with insulin treat- ences in factors that were assessed only incom- ment, or the rapid shrinking of tumors with pletely or not at all (and therefore could not be chemotherapy). -

Adaptive Clinical Trials: an Introduction

Adaptive clinical trials: an introduction What are the advantages and disadvantages of adaptive clinical trial designs? How and why were Introduction adaptive clinical Adaptive clinical trial design is trials developed? becoming a hot topic in healthcare research, with some researchers In 2004, the FDA published a report arguing that adaptive trials have the on the problems faced by the potential to get new drugs to market scientific community in developing quicker. In this article, we explain new medical treatments.2 The what adaptive trials are and why they report highlighted that the pace of were developed, and we explore both innovation in biomedical science is the advantages of adaptive designs outstripping the rate of advances and the concerns being raised by in the available technologies and some in the healthcare community. tools for evaluating new treatments. Outdated tools are being used to assess new treatments and there What are adaptive is a critical need to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of clinical trials? clinical trials.2 The current process for developing Adaptive clinical trials enable new treatments is expensive, takes researchers to change an aspect a long time and in some cases, the of a trial design at an interim development process has to be assessment, while controlling stopped after significant amounts the rate of type 1 errors.1 Interim of time and resources have been assessments can help to determine invested.2 In 2006, the FDA published whether a trial design is the most a “Critical Path Opportunities -

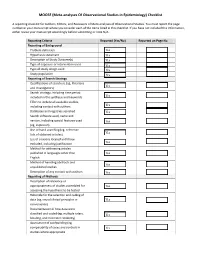

(Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist

MOOSE (Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist A reporting checklist for Authors, Editors, and Reviewers of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A. Reporting Criteria Reported (Yes/No) Reported on Page No. Reporting of Background Problem definition Hypothesis statement Description of Study Outcome(s) Type of exposure or intervention used Type of study design used Study population Reporting of Search Strategy Qualifications of searchers (eg, librarians and investigators) Search strategy, including time period included in the synthesis and keywords Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors Databases and registries searched Search software used, name and version, including special features used (eg, explosion) Use of hand searching (eg, reference lists of obtained articles) List of citations located and those excluded, including justification Method for addressing articles published in languages other than English Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies Description of any contact with authors Reporting of Methods Description of relevance or appropriateness of studies assembled for assessing the hypothesis to be tested Rationale for the selection and coding of data (eg, sound clinical principles or convenience) Documentation of how data were classified -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) Courses EPBI 2219. Biostatistics and Public Health. 3 Credit Hours. This course is designed to provide students with a solid background in applied biostatistics in the field of public health. Specifically, the course includes an introduction to the application of biostatistics and a discussion of key statistical tests. Appropriate techniques to measure the extent of disease, the development of disease, and comparisons between groups in terms of the extent and development of disease are discussed. Techniques for summarizing data collected in samples are presented along with limited discussion of probability theory. Procedures for estimation and hypothesis testing are presented for means, for proportions, and for comparisons of means and proportions in two or more groups. Multivariable statistical methods are introduced but not covered extensively in this undergraduate course. Public Health majors, minors or students studying in the Public Health concentration must complete this course with a C or better. Level Registration Restrictions: May not be enrolled in one of the following Levels: Graduate. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. EPBI 2301. Public Health without Borders. 3 Credit Hours. Public Health without Borders is a course that will introduce you to the world of disease detectives to solve public health challenges in glocal (i.e., global and local) communities. You will learn about conducting disease investigations to support public health actions relevant to affected populations. You will discover what it takes to become a field epidemiologist through hands-on activities focused on promoting health and preventing disease in diverse populations across the globe. -

A Guide to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prediction Model Performance

RESEARCH METHODS AND REPORTING A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance Thomas P A Debray,1,2 Johanna A A G Damen,1,2 Kym I E Snell,3 Joie Ensor,3 Lotty Hooft,1,2 Johannes B Reitsma,1,2 Richard D Riley,3 Karel G M Moons1,2 1Cochrane Netherlands, Validation of prediction models is diagnostic test accuracy studies. Compared to therapeu- University Medical Center tic intervention and diagnostic test accuracy studies, Utrecht, PO Box 85500 Str highly recommended and increasingly there is limited guidance on the conduct of systematic 6.131, 3508 GA Utrecht, Netherlands common in the literature. A systematic reviews and meta-analysis of primary prognosis studies. 2Julius Center for Health review of validation studies is therefore A common aim of primary prognostic studies con- Sciences and Primary Care, cerns the development of so-called prognostic predic- University Medical Center helpful, with meta-analysis needed to tion models or indices. These models estimate the Utrecht, PO Box 85500 Str 6.131, 3508 GA Utrecht, summarise the predictive performance individualised probability or risk that a certain condi- Netherlands of the model being validated across tion will occur in the future by combining information 3Research Institute for Primary from multiple prognostic factors from an individual. Care and Health Sciences, Keele different settings and populations. This Unfortunately, there is often conflicting evidence about University, Staffordshire, UK article provides guidance for the predictive performance of developed prognostic Correspondence to: T P A Debray [email protected] researchers systematically reviewing prediction models. For this reason, there is a growing Additional material is published demand for evidence synthesis of (external validation) online only. -

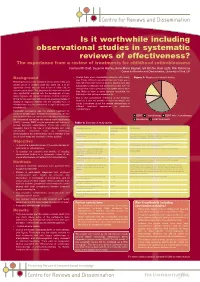

Is It Worthwhile Including Observational Studies in Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness?

CRD_mcdaid05_Poster.qxd 13/6/05 5:12 pm Page 1 Is it worthwhile including observational studies in systematic reviews of effectiveness? The experience from a review of treatments for childhood retinoblastoma Catriona Mc Daid, Suzanne Hartley, Anne-Marie Bagnall, Gill Ritchie, Kate Light, Rob Riemsma Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, UK Background • Overall there were considerable problems with quality Figure 1: Mapping of included studies (see Table). Without randomised allocation there was a Retinoblastoma is a rare malignant tumour of the retina and high risk of selection bias in all studies. Studies were also usually occurs in children under two years old. It is an susceptible to detection and performance bias, with the aggressive tumour that can lead to loss of vision and, in retrospective studies particularly susceptible as they were extreme cases, death. The prognoses for vision and survival less likely to have a study protocol specifying the have significantly improved with the development of more intervention and outcome assessments. timely diagnosis and improved treatment methods. Important • Due to the considerable limitations of the evidence clinical factors associated with prognosis are age and stage of identified, it was not possible to make meaningful and disease at diagnosis. Patients with the hereditary form of robust conclusions about the relative effectiveness of retinoblastoma may be predisposed to significant long-term different treatment approaches for childhood complications. retinoblastoma. Historically, enucleation was the standard treatment for unilateral retinoblastoma. In bilateral retinoblastoma, the eye ■ ■ ■ with the most advanced tumour was commonly removed and EBRT Chemotherapy EBRT with Chemotherapy the contralateral eye treated with external beam radiotherapy ■ Enucleation ■ Local Treatments (EBRT). -

How to Get Started with a Systematic Review in Epidemiology: an Introductory Guide for Early Career Researchers

Denison et al. Archives of Public Health 2013, 71:21 http://www.archpublichealth.com/content/71/1/21 ARCHIVES OF PUBLIC HEALTH METHODOLOGY Open Access How to get started with a systematic review in epidemiology: an introductory guide for early career researchers Hayley J Denison1*†, Richard M Dodds1,2†, Georgia Ntani1†, Rachel Cooper3†, Cyrus Cooper1†, Avan Aihie Sayer1,2† and Janis Baird1† Abstract Background: Systematic review is a powerful research tool which aims to identify and synthesize all evidence relevant to a research question. The approach taken is much like that used in a scientific experiment, with high priority given to the transparency and reproducibility of the methods used and to handling all evidence in a consistent manner. Early career researchers may find themselves in a position where they decide to undertake a systematic review, for example it may form part or all of a PhD thesis. Those with no prior experience of systematic review may need considerable support and direction getting started with such a project. Here we set out in simple terms how to get started with a systematic review. Discussion: Advice is given on matters such as developing a review protocol, searching using databases and other methods, data extraction, risk of bias assessment and data synthesis including meta-analysis. Signposts to further information and useful resources are also given. Conclusion: A well-conducted systematic review benefits the scientific field by providing a summary of existing evidence and highlighting unanswered questions. For the individual, undertaking a systematic review is also a great opportunity to improve skills in critical appraisal and in synthesising evidence. -

Adaptive Designs in Clinical Trials: Why Use Them, and How to Run and Report Them Philip Pallmann1* , Alun W

Pallmann et al. BMC Medicine (2018) 16:29 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1017-7 CORRESPONDENCE Open Access Adaptive designs in clinical trials: why use them, and how to run and report them Philip Pallmann1* , Alun W. Bedding2, Babak Choodari-Oskooei3, Munyaradzi Dimairo4,LauraFlight5, Lisa V. Hampson1,6, Jane Holmes7, Adrian P. Mander8, Lang’o Odondi7, Matthew R. Sydes3,SofíaS.Villar8, James M. S. Wason8,9, Christopher J. Weir10, Graham M. Wheeler8,11, Christina Yap12 and Thomas Jaki1 Abstract Adaptive designs can make clinical trials more flexible by utilising results accumulating in the trial to modify the trial’s course in accordance with pre-specified rules. Trials with an adaptive design are often more efficient, informative and ethical than trials with a traditional fixed design since they often make better use of resources such as time and money, and might require fewer participants. Adaptive designs can be applied across all phases of clinical research, from early-phase dose escalation to confirmatory trials. The pace of the uptake of adaptive designs in clinical research, however, has remained well behind that of the statistical literature introducing new methods and highlighting their potential advantages. We speculate that one factor contributing to this is that the full range of adaptations available to trial designs, as well as their goals, advantages and limitations, remains unfamiliar to many parts of the clinical community. Additionally, the term adaptive design has been misleadingly used as an all-encompassing label to refer to certain methods that could be deemed controversial or that have been inadequately implemented. We believe that even if the planning and analysis of a trial is undertaken by an expert statistician, it is essential that the investigators understand the implications of using an adaptive design, for example, what the practical challenges are, what can (and cannot) be inferred from the results of such a trial, and how to report and communicate the results. -

Simple Linear Regression: Straight Line Regression Between an Outcome Variable (Y ) and a Single Explanatory Or Predictor Variable (X)

1 Introduction to Regression \Regression" is a generic term for statistical methods that attempt to fit a model to data, in order to quantify the relationship between the dependent (outcome) variable and the predictor (independent) variable(s). Assuming it fits the data reasonable well, the estimated model may then be used either to merely describe the relationship between the two groups of variables (explanatory), or to predict new values (prediction). There are many types of regression models, here are a few most common to epidemiology: Simple Linear Regression: Straight line regression between an outcome variable (Y ) and a single explanatory or predictor variable (X). E(Y ) = α + β × X Multiple Linear Regression: Same as Simple Linear Regression, but now with possibly multiple explanatory or predictor variables. E(Y ) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: A special case is polynomial regression. 2 3 E(Y ) = α + β1 × X + β2 × X + β3 × X + ::: Generalized Linear Model: Same as Multiple Linear Regression, but with a possibly transformed Y variable. This introduces considerable flexibil- ity, as non-linear and non-normal situations can be easily handled. G(E(Y )) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: In general, the transformation function G(Y ) can take any form, but a few forms are especially common: • Taking G(Y ) = logit(Y ) describes a logistic regression model: E(Y ) log( ) = α + β × X + β × X + β × X + ::: 1 − E(Y ) 1 1 2 2 3 3 2 • Taking G(Y ) = log(Y ) is also very common, leading to Poisson regression for count data, and other so called \log-linear" models. -

A Systematic Review of Quasi-Experimental Study Designs in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance

INVITED ARTICLE ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE George M. Eliopoulos, Section Editor A Systematic Review of Quasi-Experimental Study Designs in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance Anthony D. Harris,1,2 Ebbing Lautenbach,3,4 and Eli Perencevich1,2 1 2 Division of Health Care Outcomes Research, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Veterans Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/41/1/77/325424 by guest on 24 September 2021 Affairs Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland; and 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, and 4Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania We performed a systematic review of articles published during a 2-year period in 4 journals in the field of infectious diseases to determine the extent to which the quasi-experimental study design is used to evaluate infection control and antibiotic resistance. We evaluated studies on the basis of the following criteria: type of quasi-experimental study design used, justification of the use of the design, use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and recognition of potential limitations of the design. A total of 73 articles featured a quasi-experimental study design. Twelve (16%) were associated with a quasi-exper- imental design involving a control group. Three (4%) provided justification for the use of the quasi-experimental study design. Sixteen (22%) used correct nomenclature to describe the study. Seventeen (23%) mentioned at least 1 of the potential limitations of the use of a quasi-experimental study design. -

A Systematic Review of COVID-19 Epidemiology Based on Current Evidence

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review A Systematic Review of COVID-19 Epidemiology Based on Current Evidence Minah Park, Alex R. Cook *, Jue Tao Lim , Yinxiaohe Sun and Borame L. Dickens Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National Health Systems, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117549, Singapore; [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (J.T.L.); [email protected] (Y.S.); [email protected] (B.L.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +65-8569-9949 Received: 18 March 2020; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 31 March 2020 Abstract: As the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) continues to spread rapidly across the globe, we aimed to identify and summarize the existing evidence on epidemiological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and the effectiveness of control measures to inform policymakers and leaders in formulating management guidelines, and to provide directions for future research. We conducted a systematic review of the published literature and preprints on the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak following predefined eligibility criteria. Of 317 research articles generated from our initial search on PubMed and preprint archives on 21 February 2020, 41 met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Current evidence suggests that it takes about 3-7 days for the epidemic to double in size. Of 21 estimates for the basic reproduction number ranging from 1.9 to 6.5, 13 were between 2.0 and 3.0. The incubation period was estimated to be 4-6 days, whereas the serial interval was estimated to be 4-8 days. Though the true case fatality risk is yet unknown, current model-based estimates ranged from 0.3% to 1.4% for outside China.