A Proposal for Reporting Meta-Analysis of Observational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic of Randomization Versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence

The new england journal of medicine Sounding Board The Magic of Randomization versus the Myth of Real-World Evidence Rory Collins, F.R.S., Louise Bowman, M.D., F.R.C.P., Martin Landray, Ph.D., F.R.C.P., and Richard Peto, F.R.S. Nonrandomized observational analyses of large safety and efficacy because the potential biases electronic patient databases are being promoted with respect to both can be appreciable. For ex- as an alternative to randomized clinical trials as ample, the treatment that is being assessed may a source of “real-world evidence” about the effi- well have been provided more or less often to cacy and safety of new and existing treatments.1-3 patients who had an increased or decreased risk For drugs or procedures that are already being of various health outcomes. Indeed, that is what used widely, such observational studies may in- would be expected in medical practice, since both volve exposure of large numbers of patients. the severity of the disease being treated and the Consequently, they have the potential to detect presence of other conditions may well affect the rare adverse effects that cannot plausibly be at- choice of treatment (often in ways that cannot be tributed to bias, generally because the relative reliably quantified). Even when associations of risk is large (e.g., Reye’s syndrome associated various health outcomes with a particular treat- with the use of aspirin, or rhabdomyolysis as- ment remain statistically significant after adjust- sociated with the use of statin therapy).4 Non- ment for all the known differences between pa- randomized clinical observation may also suf- tients who received it and those who did not fice to detect large beneficial effects when good receive it, these adjusted associations may still outcomes would not otherwise be expected (e.g., reflect residual confounding because of differ- control of diabetic ketoacidosis with insulin treat- ences in factors that were assessed only incom- ment, or the rapid shrinking of tumors with pletely or not at all (and therefore could not be chemotherapy). -

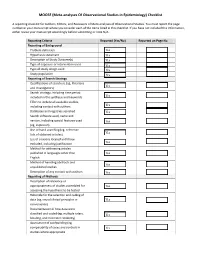

(Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist

MOOSE (Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist A reporting checklist for Authors, Editors, and Reviewers of Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. You must report the page number in your manuscript where you consider each of the items listed in this checklist. If you have not included this information, either revise your manuscript accordingly before submitting or note N/A. Reporting Criteria Reported (Yes/No) Reported on Page No. Reporting of Background Problem definition Hypothesis statement Description of Study Outcome(s) Type of exposure or intervention used Type of study design used Study population Reporting of Search Strategy Qualifications of searchers (eg, librarians and investigators) Search strategy, including time period included in the synthesis and keywords Effort to include all available studies, including contact with authors Databases and registries searched Search software used, name and version, including special features used (eg, explosion) Use of hand searching (eg, reference lists of obtained articles) List of citations located and those excluded, including justification Method for addressing articles published in languages other than English Method of handling abstracts and unpublished studies Description of any contact with authors Reporting of Methods Description of relevance or appropriateness of studies assembled for assessing the hypothesis to be tested Rationale for the selection and coding of data (eg, sound clinical principles or convenience) Documentation of how data were classified -

Quasi-Experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: a Systematic Review

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Infect Control Manuscript Author Hosp Epidemiol Manuscript Author . Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 November 12. Published in final edited form as: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018 February ; 39(2): 170–176. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.296. Quasi-experimental Studies in the Fields of Infection Control and Antibiotic Resistance, Ten Years Later: A Systematic Review Rotana Alsaggaf, MS, Lyndsay M. O’Hara, PhD, MPH, Kristen A. Stafford, PhD, MPH, Surbhi Leekha, MBBS, MPH, Anthony D. Harris, MD, MPH, CDC Prevention Epicenters Program Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Abstract OBJECTIVE.—A systematic review of quasi-experimental studies in the field of infectious diseases was published in 2005. The aim of this study was to assess improvements in the design and reporting of quasi-experiments 10 years after the initial review. We also aimed to report the statistical methods used to analyze quasi-experimental data. DESIGN.—Systematic review of articles published from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2014, in 4 major infectious disease journals. METHODS.—Quasi-experimental studies focused on infection control and antibiotic resistance were identified and classified based on 4 criteria: (1) type of quasi-experimental design used, (2) justification of the use of the design, (3) use of correct nomenclature to describe the design, and (4) statistical methods used. RESULTS.—Of 2,600 articles, 173 (7%) featured a quasi-experimental design, compared to 73 of 2,320 articles (3%) in the previous review (P<.01). Moreover, 21 articles (12%) utilized a study design with a control group; 6 (3.5%) justified the use of a quasi-experimental design; and 68 (39%) identified their design using the correct nomenclature. -

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1

Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) 1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics (EPBI) Courses EPBI 2219. Biostatistics and Public Health. 3 Credit Hours. This course is designed to provide students with a solid background in applied biostatistics in the field of public health. Specifically, the course includes an introduction to the application of biostatistics and a discussion of key statistical tests. Appropriate techniques to measure the extent of disease, the development of disease, and comparisons between groups in terms of the extent and development of disease are discussed. Techniques for summarizing data collected in samples are presented along with limited discussion of probability theory. Procedures for estimation and hypothesis testing are presented for means, for proportions, and for comparisons of means and proportions in two or more groups. Multivariable statistical methods are introduced but not covered extensively in this undergraduate course. Public Health majors, minors or students studying in the Public Health concentration must complete this course with a C or better. Level Registration Restrictions: May not be enrolled in one of the following Levels: Graduate. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. EPBI 2301. Public Health without Borders. 3 Credit Hours. Public Health without Borders is a course that will introduce you to the world of disease detectives to solve public health challenges in glocal (i.e., global and local) communities. You will learn about conducting disease investigations to support public health actions relevant to affected populations. You will discover what it takes to become a field epidemiologist through hands-on activities focused on promoting health and preventing disease in diverse populations across the globe. -

Observational Clinical Research

E REVIEW ARTICLE Clinical Research Methodology 2: Observational Clinical Research Daniel I. Sessler, MD, and Peter B. Imrey, PhD * † Case-control and cohort studies are invaluable research tools and provide the strongest fea- sible research designs for addressing some questions. Case-control studies usually involve retrospective data collection. Cohort studies can involve retrospective, ambidirectional, or prospective data collection. Observational studies are subject to errors attributable to selec- tion bias, confounding, measurement bias, and reverse causation—in addition to errors of chance. Confounding can be statistically controlled to the extent that potential factors are known and accurately measured, but, in practice, bias and unknown confounders usually remain additional potential sources of error, often of unknown magnitude and clinical impact. Causality—the most clinically useful relation between exposure and outcome—can rarely be defnitively determined from observational studies because intentional, controlled manipu- lations of exposures are not involved. In this article, we review several types of observa- tional clinical research: case series, comparative case-control and cohort studies, and hybrid designs in which case-control analyses are performed on selected members of cohorts. We also discuss the analytic issues that arise when groups to be compared in an observational study, such as patients receiving different therapies, are not comparable in other respects. (Anesth Analg 2015;121:1043–51) bservational clinical studies are attractive because Group, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists they are relatively inexpensive and, perhaps more Anesthesia Quality Institute. importantly, can be performed quickly if the required Recent retrospective perioperative studies include data O 1,2 data are already available. -

Guidelines for Reporting Meta-Epidemiological Methodology Research

EBM Primer Evid Based Med: first published as 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 on 12 July 2017. Downloaded from Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research Mohammad Hassan Murad, Zhen Wang 10.1136/ebmed-2017-110713 Abstract The goal is generally broad but often focuses on exam- Published research should be reported to evidence users ining the impact of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the observed effect, describing the distribu- Evidence-Based Practice with clarity and transparency that facilitate optimal tion of research evidence in a specific setting, exam- Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, appraisal and use of evidence and allow replication Minnesota, USA by other researchers. Guidelines for such reporting ining heterogeneity and exploring its causes, identifying are available for several types of studies but not for and describing plausible biases and providing empirical meta-epidemiological methodology studies. Meta- evidence for hypothesised associations. Unlike classic Correspondence to: epidemiological studies adopt a systematic review epidemiology, the unit of analysis for meta-epidemio- Dr Mohammad Hassan Murad, or meta-analysis approach to examine the impact logical studies is a study, not a patient. The outcomes Evidence-based Practice Center, of certain characteristics of clinical studies on the of meta-epidemiological studies are usually not clinical Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street 6–8 observed effect and provide empirical evidence for outcomes. SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA; hypothesised associations. The unit of analysis in meta- In this guide, we adapt the items used in the PRISMA murad. mohammad@ mayo. edu 9 epidemiological studies is a study, not a patient. The statement for reporting systematic reviews and outcomes of meta-epidemiological studies are usually meta-analysis to fit the setting of meta- epidemiological not clinical outcomes. -

Observational Studies and Bias in Epidemiology

The Young Epidemiology Scholars Program (YES) is supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and administered by the College Board. Observational Studies and Bias in Epidemiology Manuel Bayona Department of Epidemiology School of Public Health University of North Texas Fort Worth, Texas and Chris Olsen Mathematics Department George Washington High School Cedar Rapids, Iowa Observational Studies and Bias in Epidemiology Contents Lesson Plan . 3 The Logic of Inference in Science . 8 The Logic of Observational Studies and the Problem of Bias . 15 Characteristics of the Relative Risk When Random Sampling . and Not . 19 Types of Bias . 20 Selection Bias . 21 Information Bias . 23 Conclusion . 24 Take-Home, Open-Book Quiz (Student Version) . 25 Take-Home, Open-Book Quiz (Teacher’s Answer Key) . 27 In-Class Exercise (Student Version) . 30 In-Class Exercise (Teacher’s Answer Key) . 32 Bias in Epidemiologic Research (Examination) (Student Version) . 33 Bias in Epidemiologic Research (Examination with Answers) (Teacher’s Answer Key) . 35 Copyright © 2004 by College Entrance Examination Board. All rights reserved. College Board, SAT and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Entrance Examination Board. Other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.com. Copyright © 2004. All rights reserved. 2 Observational Studies and Bias in Epidemiology Lesson Plan TITLE: Observational Studies and Bias in Epidemiology SUBJECT AREA: Biology, mathematics, statistics, environmental and health sciences GOAL: To identify and appreciate the effects of bias in epidemiologic research OBJECTIVES: 1. Introduce students to the principles and methods for interpreting the results of epidemio- logic research and bias 2. -

Study Types Transcript

Study Types in Epidemiology Transcript Study Types in Epidemiology Welcome to “Study Types in Epidemiology.” My name is John Kobayashi. I’m on the Clinical Faculty at the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, at the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Washington in Seattle. From 1982 to 2001, I was the state epidemiologist for Communicable Diseases at the Washington State Department of Health. Since 2001, I’ve also been the foreign adviser for the Field Epidemiology Training Program of Japan. About this Module The modules in the epidemiology series from the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice are intended for people working in the field of public health who are not epidemiologists, but who would like to increase their understanding of the epidemiologic approach to health and disease. This module focuses on descriptive and analytic epide- miology and their respective study designs. Before you go on with this module, we recommend that you become familiar with the following modules, which you can find on the Center’s Web site: What is Epidemiology in Public Health? and Data Interpretation for Public Health Professionals. We introduce a number of new terms in this module. If you want to review their definitions, the glossary in the attachments link at the top of the screen may be useful. Objectives By now, you should be familiar with the overall approach of epidemiology, the use of various kinds of rates to measure disease frequency, and the various ways in which epidemiologic data can be presented. This module offers an overview of descriptive and analytic epidemiology and the types of studies used to review and investigate disease occurrence and causes. -

Simple Linear Regression: Straight Line Regression Between an Outcome Variable (Y ) and a Single Explanatory Or Predictor Variable (X)

1 Introduction to Regression \Regression" is a generic term for statistical methods that attempt to fit a model to data, in order to quantify the relationship between the dependent (outcome) variable and the predictor (independent) variable(s). Assuming it fits the data reasonable well, the estimated model may then be used either to merely describe the relationship between the two groups of variables (explanatory), or to predict new values (prediction). There are many types of regression models, here are a few most common to epidemiology: Simple Linear Regression: Straight line regression between an outcome variable (Y ) and a single explanatory or predictor variable (X). E(Y ) = α + β × X Multiple Linear Regression: Same as Simple Linear Regression, but now with possibly multiple explanatory or predictor variables. E(Y ) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: A special case is polynomial regression. 2 3 E(Y ) = α + β1 × X + β2 × X + β3 × X + ::: Generalized Linear Model: Same as Multiple Linear Regression, but with a possibly transformed Y variable. This introduces considerable flexibil- ity, as non-linear and non-normal situations can be easily handled. G(E(Y )) = α + β1 × X1 + β2 × X2 + β3 × X3 + ::: In general, the transformation function G(Y ) can take any form, but a few forms are especially common: • Taking G(Y ) = logit(Y ) describes a logistic regression model: E(Y ) log( ) = α + β × X + β × X + β × X + ::: 1 − E(Y ) 1 1 2 2 3 3 2 • Taking G(Y ) = log(Y ) is also very common, leading to Poisson regression for count data, and other so called \log-linear" models. -

Chapter 5 Experiments, Good And

Chapter 5 Experiments, Good and Bad Point of both observational studies and designed experiments is to identify variable or set of variables, called explanatory variables, which are thought to predict outcome or response variable. Confounding between explanatory variables occurs when two or more explanatory variables are not separated and so it is not clear how much each explanatory variable contributes in prediction of response variable. Lurking variable is explanatory variable not considered in study but confounded with one or more explanatory variables in study. Confounding with lurking variables effectively reduced in randomized comparative experiments where subjects are assigned to treatments at random. Confounding with a (only one at a time) lurking variable reduced in observational studies by controlling for it by comparing matched groups. Consequently, experiments much more effec- tive than observed studies at detecting which explanatory variables cause differences in response. In both cases, statistically significant observed differences in average responses implies differences are \real", did not occur by chance alone. Exercise 5.1 (Experiments, Good and Bad) 1. Randomized comparative experiment: effect of temperature on mice rate of oxy- gen consumption. For example, mice rate of oxygen consumption 10.3 mL/sec when subjected to 10o F. temperature (Fo) 0 10 20 30 ROC (mL/sec) 9.7 10.3 11.2 14.0 (a) Explanatory variable considered in study is (choose one) i. temperature ii. rate of oxygen consumption iii. mice iv. mouse weight 25 26 Chapter 5. Experiments, Good and Bad (ATTENDANCE 3) (b) Response is (choose one) i. temperature ii. rate of oxygen consumption iii. -

Analytic Epidemiology Analytic Studies: Observational Study

Analytic Studies: Observational Study Designs Cohort Studies Analytic Epidemiology Prospective Cohort Studies Retrospective (historical) Cohort Studies Part 2 Case-Control Studies Nested case-control Case-cohort studies Dr. H. Stockwell Case-crossover studies Determinants of disease: Analytic Epidemiology Epidemiology: Risk factors Identifying the causes of disease A behavior, environmental exposure, or inherent human characteristic that is associated with an important health Testing hypotheses using epidemiologic related condition* studies Risk factors are associated with an increased probability of disease but may Goal is to prevent disease (deterrents) not always cause the diseases *Last, J. Dictionary of Epidemiology Analytic Studies: Cohort Studies Panel Studies Healthy subjects are defined by their Combination of cross-sectional and exposure status and followed over time to cohort determine the incidence of disease, symptoms or death Same individuals surveyed at several poiiiints in time Subjects grouped by exposure level – exposed and unexposed (f(reference group, Can measure changes in individuals comparison group) Analytic Studies: Case-Control Studies Nested case-control studies A group of individuals with a disease Case-control study conducted within a (cases) are compared with a group of cohort study individuals without the disease (controls) Advantages of both study designs Also called a retrospective study because it starts with people with disease and looks backward for ppprevious exposures which might be -

1 Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-‐Value

Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-value Tyler J. VanderWeele, Ph.D., Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Peng Ding, Ph.D., Department of Statistics, University of California, Berkeley This is the prepublication, author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in Annals of Internal Medicine. This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The American College of Physicians, the publisher of Annals of Internal Medicine, is not responsible for the content or presentation of the author-produced accepted version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to this manuscript (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, linked articles) should go to Annals.org or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record: VanderWeele, T.J. and Ding, P. (2017). Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(4):268-274. 1 Abstract. Sensitivity analysis can be useful in assessing how robust associations are to potential unmeasured or uncontrolled confounding. In this paper we introduce a new measure that we call the “E-value,” a measure related to the evidence for causality in observational studies, when they are potentially subject to confounding. The E-value is defined as the minimum strength of association on the risk ratio scale that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the treatment and the outcome to fully eXplain away a specific treatment-outcome association, conditional on the measured covariates.