Life, Background, Literary and Social Milieu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

REPORT to COUNCIL City.Of Sacramento 23 915 I Street, Sacramento, CA 95814-2604 Www

REPORT TO COUNCIL City.of Sacramento 23 915 I Street, Sacramento, CA 95814-2604 www. CityofSacramento.org Staff Report May 11,2010 Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council Title: Leases - Digital Billboards on City-owned Sites Location/Council District: Citywide Recommendation: Adopt a Resolution 1) approving four separate leases between the City of Sacramento and Clear Channel Outdoor, Inc. governing the installation and operation of digital billboards on four city-owned sites located at the north side of Interstate 80 east of Northgate Boulevard (APN: 237-0031-36), Business 80 and Fulton Avenue (3630 Fulton Avenue, APN: 254-0310-002), west side of Highway 99, south of Mack Road (APN: 117-0170-067), and west side of Interstate 5 south of Richards Boulevard (240 Jibboom Street, APN: 001-0190-015); 2) authorizing the City Manager to execute the leases on the City's behalf. Contact: Tom Zeidner, Senior Development Project Manager, 808-1931 Presenters: Tom Zeidner, Senior Development Project Manager Department: Economic Development Division: Citywide Organization No: 18001031 Description/Analysis Issue: Overview. On August 25, 2009, the City Council granted Clear Channel Outdoor, Inc. the exclusive right to negotiate with the City for the installation and operation of digital billboards on City-owned sites near major freeways. On March 23, 2010, staff reported to the City Council that negotiations were complete successfully, that the resulting terms were being incorporated into separate leases for each of the four new proposed billboards, that proceeding with the digital-billboards project required an amendment to the City's Sign Code, and that as part of the project CCO would remove a number of existing "static" billboards. -

The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria

Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol The cities and cemeteries of Etruria Dennis, George 1883 Chapter XV Bombarzo urn:nbn:at:at-ubi:2-12107 CHAPTER XV. BOHABZO. Miremur periisse homines ?—monnmenta fatiscunt, Mors etiam saxis nominibusque venit .—Ausonius. Ecce libet-pisces Tyrrhenaque monstra Dicere. Ovid. About twelve miles east of Viterbo, on the same slope of the Ciminian, is the village of Bomarzo, in the immediate neighbour¬ hood of an Etruscan town where extensive excavations have been made. The direct road to it runs along the base of the mountain, but the excursion may be made more interesting by a detour to Fdrento, which must be donfe in the saddle, the road being quite impracticable for vehicles. From Ferento the path leads across a deep ravine, past the village of Le Grotte di Santo Stefano, whose name marks the existence of caves in its neighbourhood,1 and over the open heath towards Bomarzo. But before reaching that place, a wooded ravine, Fosso della Vezza, which forms a natural fosse to the Ciminian, has to be crossed, and here the proverb —Chi va piano va sano —must be borne in mind. A more steep, slippery, and dangerous tract I do not remember to have traversed in Italy. Stiff miry clay, in which the steeds will anchor fast ; rocks shelving and smooth-faced, like inclined planes of ice, are the alternatives. Let the traveller take warning, and not pursue this track after heavy rains. It would be advisable, especially if ladies are of the party, to return from Ferento to Viterbo, and to take the direct road thence to Bomarzo. -

Co-Production Forum

CO-PRODUCTION FORUM 1 CONTENT PITCH SESSION : GAP FINANCING SESSIONS PITCHER BAYO BAYO BABY KANAKI FILMS - SPAIN 4 by Amaia Remírez & Raúl de la Fuente PITCHER BIRDS DON’T LOOK BACK SPECIAL TOUCH STUDIOS - 5 by Nadia Nakhlé FRANCE DIRTY LAND PITCHER BRO CINEMA - PORTUGAL 6 by Luis Campos PITCHER DREAMING OF LIONS PERSONA NON GRATA 7 by Paolo Marinou-Blanco PORTUGAL PITCHER AN ENEMY POKROMSKI STUDIO - POLAND 8 by Teresa Zofia Czepiec PITCHER FIRES CODE BLUE PRODUCTION D.O.O. - 9 by Nikola Ljuca MONTENEGRO PITCHER THE GLASS HOUSE DIRECTORY FILMS - UKRAINE 10 by Taras Dron PITCHER OUR FATHER THIS AND THAT PRODUCTIONS 11 by Goran Stankovic SERBIA PITCHER SOULS ON TAPE VILDA BOMBEN FILM AB 12 by Carl Javér SWEDEN PITCH SESSION : UP : UP-AND-COMING PRODUCERS PITCHER ARTURO’S VOICE MATRIOSKA - ITALY 14 by Irene Dionisio PITCHER AUTONAUTS OF THE COSMOROUTE IKKI FILMS - FRANCE 15 by Olivier Gondry & Leslie Menahem PITCHER CLEAN CARTOUCHE BVBA - BELGIUM by Koen Van Sande 16 PITCHER THE FURY RINGO MEDIA - SPAIN 17 by Gemma Blasco GROUND ZERO PITCHER RADAR FILMS - UKRAINE 18 by Zhanna Ozirna PINOT FILMS - POLAND PITCHER IN BETWEEN 19 by Piotr Lewandowski PITCHER SHINY NEW WORLD MAKE WAY FILM - NETHERLANDS 20 by Jan van Gorkum THREE SONGS CORTE A FILMS - SPAIN PITCHER 21 by Adrià Guxens PITCHER THE VIRGIN AND THE CHILD PLAYTIME FILMS - BELGIUM 22 by Binevsa Berivan PITCHER ZEJTUNE (UNTITLED GHANA PROJECT) LUZZU LTD - MALTA 23 by Alex Camilleri TIMETABLE 24 PITCH SESSION : GAP FINANCING SESSIONS 3 BAYO BAYO BABY - FICTION SPAIN Every night Aminata patrols the streets of Freetown searching for girls being exploited by pimps. -

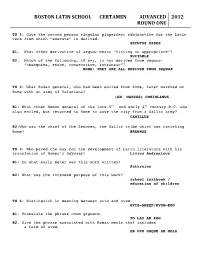

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

What the 'New Intergovernmentalism' Can Tell Us About the Greek Crisis

What the ‘new intergovernmentalism’ can tell us about the Greek crisis blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/08/26/what-the-new-intergovernmentalism-can-tell-us-about-the-greek-crisis/ 8/26/2015 A number of authors have argued that a ‘new intergovernmentalism’ has come to characterise EU decision-making since the financial crisis, with decisions increasingly made through intergovernmental negotiations such as those in the European Council. Christopher Bickerton writes on what the theory can tell us about the Greek crisis, noting that it helps illustrate both the febrile nature of domestic politics in Greece and why the Syriza government was ultimately unsuccessful in its attempts to secure concessions from the country’s creditors. Just as some thought it was over, the Greek crisis has entered into a new and dramatic stage. The Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has declared snap elections to be held on 20 September. This comes just as the European Stability Mechanism had transferred 13 billion euros to Athens, out of which 3.2 billion was immediately sent to the European Central Bank to repay a bond of that amount due on 20 August. Tsipras has calculated that with public backing for the third bail-out, he can use the election to rid himself of the left block faction (Popular Unity) within Syriza, which has been vigorously opposing the bail-out deal. He can then recast himself as a more centrist figure, while the left-wing faction re-launches itself as an anti-austerity, anti-bailout party. The new intergovernmentalism and the Greek crisis What might the new intergovernmentalism have to tell us about the Greek crisis? It is always tricky to use theories to explain a moving target, especially one as protean as the Greek crisis, but there are at least three insights into the crisis that the new intergovernmentalism can provide us with. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU 1. Translate this sentence into English: Servābuntne nōs Rōmānī, sī Persae īrātī vēnerint? WILL THE ROMANS SAVE US IF THE ANGRY PERSIANS COME? B1: What kind of conditional is illustrated in that sentence? FUTURE MORE VIVID B2: Now translate this sentence into English: Haec nōn loquerēris nisi tam stultus essēs. YOU WOULD NOT SAY THESE THINGS IF YOU WERE NOT SO STUPID TU 2. What versatile author may be the originator of satire, but is more famous for writing fabulae praetextae, fabulae palliatae, and the Annales? (QUINTUS) ENNIUS B1: What silver age author remarked that Ennius had three hearts on account of his trilingualism? AULUS GELLIUS B2: Give one example either a fabula praetexta or a fabula palliata of Ennius. AMBRACIA, CAUPUNCULA, PANCRATIASTES TU 3. What modern slang word, deriving from the Latin word for “four,” is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “crew, posse, gang; an informal group of individuals with a common identity and a sense of solidarity”? SQUAD B1: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “bend”, means “subtly or not-so-subtly showing off your accomplishments or possessions”? FLEX B2: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “end” and defined by the Urban Dictionary as “a word that modern teens and preteens say even though they have absolutely no idea what it really means,” roughly means “getting around issues or problems in a slick or easy way”? FINESSE TU 4. Who elevated his son Diadumenianus to the rank of Caesar when he became emperor in 217 A.D.? MACRINUS B1: Where did Macrinus arrange for the assisination of Caracalla? CARRHAE/EDESSA B2: What was the name of the person who actually did the stabbing of Caracalla? JULIUS MARTIALIS TU 5. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

Music Sampling and Copyright Law

CACPS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS #1, SPRING 1999 MUSIC SAMPLING AND COPYRIGHT LAW by John Lindenbaum April 8, 1999 A Senior Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My parents and grandparents for their support. My advisor Stan Katz for all the help. My research team: Tyler Doggett, Andy Goldman, Tom Pilla, Arthur Purvis, Abe Crystal, Max Abrams, Saran Chari, Will Jeffrion, Mike Wendschuh, Will DeVries, Mike Akins, Carole Lee, Chuck Monroe, Tommy Carr. Clockwork Orange and my carrelmates for not missing me too much. Don Joyce and Bob Boster for their suggestions. The Woodrow Wilson School Undergraduate Office for everything. All the people I’ve made music with: Yamato Spear, Kesu, CNU, Scott, Russian Smack, Marcus, the Setbacks, Scavacados, Web, Duchamp’s Fountain, and of course, Muffcake. David Lefkowitz and Figurehead Management in San Francisco. Edmund White, Tom Keenan, Bill Little, and Glenn Gass for getting me started. My friends, for being my friends. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................……………………...1 History of Musical Appropriation........................................................…………………6 History of Music Copyright in the United States..................................………………17 Case Studies....................................................................................……………………..32 New Media......................................................................................……………………..50 -

OLD FLORENCE and MODERN TUSCANY Books by the Same Author

\> s %w n vj- jo>" <riuoNvso^ "%jaim jv\v CAIIF0%, ^OFCALIFOfy^ .\Wl)NIVERS//, ^lOS-ANCflfj> k avnan-# ^AHVHaiB^ <Ti130KVS01^ %UMNfUWV Or ^lOSANCHfj^ s&HIBRARYQr ^tllBRARYQr jonv-sov^ ^/MAINfHtW ^0JITV3JO^ ^fOJITCHO^ ^clOSANCflfj> ^OFCAllF0fy> ^OFCAllFOfy* y6>A«va8n^ ^ILIBRARY^ ^EUNIVERS/a v^lOSANCFlfj> ^TilJDNV-SOl^ ^uainihwv" ^OFCAUFOfy* «AVK-UNIVERJ/a vj^lOSANCfl^ ^AHvaan-3^ i»soi^ 'fySMAINA-flfc* UNIVERT/a «AUI8RAR" wfrllBRARYfl/v ^JDNV-SQl^ ^MAINA-fl^ >• 1 ^*^T T © c? 3s. y& ^?AavHan# AfcUK-ANGElfj> ^t LIBRARY/^ 4$UIBRARY0/ > =z li ^ ce o %3MN(1MV >2- ^lOS-ANCEtfju ^0FCAItF(% ^OFCAllFOfy* o : 1^ /0* A o o I? ^/hhainii-mv y0Aavaan# Y-Or ^UIBKARY0/ ^WtUN!VERi'/A >^UfcANCElfJ> jO^ ^OillVJJO^ <^HDNV-S0V^ ^/mainihw^ Q ^OFCAllFOfi^ AttEUNIVERS/A ^clOSANCElfj^ \ 4^ % N B* y0AUvaan^ <^U3NVS0V^ ^saBAiNfi aW^* R% **UK-ANCHfj> ^tfUBRARYQr ^tllBRARYQr r 1 H-^£ k)g 3 OLD FLORENCE AND MODERN TUSCANY books by the same author Florentine Villas Illustrated with Photogravure Reproduc- tions of Zocchi's Engravings of the Villas ; of sixteen Medals in the Bargello; and of a Death Mask of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Also with text illustrations by Nf.i.i.y Erichskn. Also a Large Paper Edition. Imperial 4to, £$ Jf.net. Leaves from our Tuscan Kitchen ; or how to cook vegetables With Photogravure Frontispiece. Fools- cap Svo, zs. 6d. net. [Third Edition. Letters from the East, 1837-1857 By Hf.nrv James Ross. Edited by his Wile, Janet Ross. With Photogravure Portraits, and Illustrations from Photo- graphs. Demy 8vo, 12s. 6d. net. In preparation Florentine Palaces f 3 ^ '* — OLD FLORENCE AND MODERN TUSCANY BY JANET ROSS v '.OW'ttJflBl L«f i**J>-l>W.