Roman Satire and Its Inflllence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria

Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol The cities and cemeteries of Etruria Dennis, George 1883 Chapter XV Bombarzo urn:nbn:at:at-ubi:2-12107 CHAPTER XV. BOHABZO. Miremur periisse homines ?—monnmenta fatiscunt, Mors etiam saxis nominibusque venit .—Ausonius. Ecce libet-pisces Tyrrhenaque monstra Dicere. Ovid. About twelve miles east of Viterbo, on the same slope of the Ciminian, is the village of Bomarzo, in the immediate neighbour¬ hood of an Etruscan town where extensive excavations have been made. The direct road to it runs along the base of the mountain, but the excursion may be made more interesting by a detour to Fdrento, which must be donfe in the saddle, the road being quite impracticable for vehicles. From Ferento the path leads across a deep ravine, past the village of Le Grotte di Santo Stefano, whose name marks the existence of caves in its neighbourhood,1 and over the open heath towards Bomarzo. But before reaching that place, a wooded ravine, Fosso della Vezza, which forms a natural fosse to the Ciminian, has to be crossed, and here the proverb —Chi va piano va sano —must be borne in mind. A more steep, slippery, and dangerous tract I do not remember to have traversed in Italy. Stiff miry clay, in which the steeds will anchor fast ; rocks shelving and smooth-faced, like inclined planes of ice, are the alternatives. Let the traveller take warning, and not pursue this track after heavy rains. It would be advisable, especially if ladies are of the party, to return from Ferento to Viterbo, and to take the direct road thence to Bomarzo. -

Some Problems in Prosody

1903·] Some Problems in Prosody. 33 ARTICLE III. SOME PROBLEMS IN PROSODY. BY PI10PlCSSOI1 R.aBUT W. KAGOUN, PR.D. IT has been shown repeatedly, in the scientific world, that theory must be supplemented by practice. In some cases, indeed, practice has succeeded in obtaining satisfac tory results after theory has failed. Deposits of Urate of Soda in the joints, caused by an excess of Uric acid in the blood, were long held to be practically insoluble, although Carbonate of Lithia was supposed to have a solvent effect upon them. The use of Tetra·Ethyl-Ammonium Hydrox ide as a medicine, to dissolve these deposits and remove the gout and rheumatism which they cause, is said to be due to some experiments made by Edison because a friend of his had the gout. Mter scientific men had decided that electric lighting could never be made sufficiently cheap to be practicable, he discovered the incandescent lamp, by continuing his experiments in spite of their ridicule.1 Two young men who "would not accept the dictum of the authorities that phosphorus ... cannot be expelled from iron ores at a high temperature, ... set to work ... to see whether the scientific world had not blundered.'" To drive the phosphorus out of low-grade ores and convert them into Bessemer steel, required a "pot-lining" capable of enduring 25000 F. The quest seemed extraordinary, to say the least; nevertheless the task was accomplished. This appears to justify the remark that "Thomas is our modem Moses";8 but, striking as the figure is, the young ICf. -

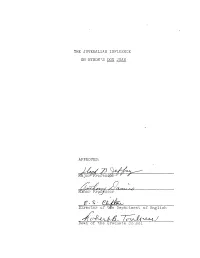

The Juvenalian Influence on Byronts Don Juan Approved

THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRONTS DON JUAN APPROVED: \ Minor Professor Director of tfefe Department of English Dean of the Graduate Sci'iool THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRON'S DON JUAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Diane Gardner Dunson, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1967 PREFACE This thesis is a comparative study of Juvenal and Lord Byron, with emphasis on the particularly kindred aspects of the poets' works. The two men lived hundreds of years apart, yet their ideas and attitudes are so similar that the con- nection bears research. In many instances, the relationship between the poets is only temperamental; at other times, the subject matter of Byron reveals the direct influence of Ju- venal. This paper treats in detail the major topics of in- terest which Juvenal and Byron shared—society, morality, war, death, and the purpose of life. The first chapter on' the nature of satire serves as an introduction to the study of these topics and is designed to bridge the time gap be- tween the poets. The backgrounds of Juvenal and Byron are considered briefly to show the comparable social and politi- cal atmosphere of their early manhood. The remaining three chapters deal in detail with the subject matter of Juvenal's Satires and Byron's Don Juan, with emphasis on the modernity, soundness of judgement, and worth of that which the two men have to say. For the particular study of the Juvenalian influence on Lord Byron, and especially on Don Juan, there were no iii specific books available. -

Introduction Lucilius and Second- Century Rome Brian W

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-18955-3 — Lucilius and Satire in Second-Century BC Rome Edited by Brian W. Breed , Elizabeth Keitel , Rex Wallace Excerpt More Information 1 Chapter 1 Introduction Lucilius and Second- Century Rome Brian W. Breed , Rex Wallace , and Elizabeth Keitel 1 ut noster Lucilius Gaius Lucilius, writing in the last third of the second century bc , eff ec- tively created the one literary genre that Romans thought of as “entirely ours,” tota nostra . For Quintilian , whose characterization of satire this is, the tradition founded by Lucilius is distinctly Roman because, unlike other genres, it is not directly taken from the Greeks. 1 Th at element of diff erentiation from established generic canons is important at the time Lucilius was writing, but there is much more to what makes Roman satire from the beginning so crucially “ours,” 2 and the poet so distinctively “one of us” in the eyes of his fellow Romans. Lucilius’ poems respond deeply to the cultural conditions in which they were created, and they give infl u- ential expression to forms and varied meanings of Roman identity. In the hands of other poets satire would continue to draw energy from the culture around it, even as defi nitions of Romanness , and Rome itself, changed. Th e texts of later Roman satirists inspired by Lucilius’ model were writ- ten after the republic that Lucilius knew and depicted in his poems had ceased to function. With this in mind Kirk Freudenburg has infl uentially called Lucilius a problem for the tradition he created. 3 As spokesman for and embodiment of a republican past, and in particular of republican lib- ertas , Lucilius founds a genre identifi ed with free speaking, so that later authors, writing under the restraints of changed political and social cir- cumstances, can never hope to attain the ideal generic purpose that was achieved by the founding father. -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave". -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

Blame As Consolation: Rehabilitating the Iambic in Horace's Post-Actian Symposia" (2014)

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 4-23-2014 Blame as Consolation: Rehabilitating the Iambic in Horace's Post- Actian Symposia Emma C. Oestreicher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Oestreicher, Emma C., "Blame as Consolation: Rehabilitating the Iambic in Horace's Post-Actian Symposia" (2014). Student Research Submissions. 109. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/109 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLAME AS CONSOLATION: REHABILITATING THE IAMBIC IN HORACE'S POST-ACTIAN SYMPOSIA An honors paper submitted to the Department of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Emma C. Oestreicher April 2014 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Emma Oestreicher 05/01/15 (digital signature) BLAME AS CONSOLATION: REHABILITATING THE IAMBIC IN HORACE’S POST-ACTIAN SYMPOSIA A THESIS BY EMMA -

METRE and TEXT* Andromache Has Spoken the Prologue (1–55)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN EURIPIDES, ANDROMACHE 103–125: METRE AND TEXT* (Αν.) Ἰλίωι αἰπεινᾶι Πάριϲ οὐ γάµον ἀλλά τιν’ ἄταν ἀγάγετ’ εὐναίαν ἐϲ θαλάµουϲ ῾Єλέναν· · · · · · · · · · · πρὸϲ τόδ’ ἄγαλµα θεᾶϲ ἱκέτιϲ περὶ χεῖρε βαλοῦϲα 115 τάκοµαι ὡϲ πετρίνα πιδακόεϲϲα λιβάϲ. ΧΟΡΟΣ ὦ γύναι, ἃ Θέτιδοϲ δάπεδον καὶ ἀνάκτορα θάϲϲειϲ δαρὸν oὐδὲ λείπειϲ, Φθιὰϲ ὅµωϲ ἔµολον ποτὶ ϲὰν Ἀϲιήτιδα γένναν, εἴ τί ϲοι δυναί µ 120αν ἄκοϲ τῶν δυϲλύτων πόνων τεµεῖν, οἵ ϲε καὶ ῾Єρµιόναν ἔριδι ϲτυγερᾶι ϲυνέκληιϲαν τλάµον’ ἀµφὶ λέκτρων διδύµων ἐπίκοινον †ἐοῦϲαν† ἀµφὶ παῖδ’ Ἀχιλλέωϲ· 125 104 ἀγάγετ’ Dindorf: ἠγ- codd. 121 rectius ταµεῖν? 123 τλάµον’ P: -µων L, -µονα cett.; τλᾶµον Ald. Andromache has spoken the prologue (1–55), followed by dialogue with a maidservant (56–90) and further soliloquy (91–102), from which she proceeds to sing an unusual elegiac lament (103–16).1 This in turn serves as a proem to the Parodos,2, whose first stanza contains ——— * Mnemosyne 54 (2001), 724–30. 1 The transition from speech to song without speaker-change is already unusual. There are no other elegiacs in tragedy; but the words ἐλεγεῖον (the earliest attestations referring to epitaphs) and ἔλεγοϲ (first attested of elegiacs in Calli- machus) are certainly cognate. A hypothesis of precedents in 7th–6th century N. Peloponnesian poetry (D. L. Page in Greek Poetry and Life (Oxford, 1938), 206–30) is plausible, but does little to account for the form here. More certainly relevant are the elevated quality of dactylic metre (with epic colour) on Andromache’s lips; the appropriateness of repetition in threnody (here ‘epodic’); and (last but not least) the juxtaposition of 103–16 with 117 ff. -

An Introduction to Latin Literature and Style Pursue in Greater Depth; (C) It Increases an Awareness of Style and Linguistic Structure

An Introduction to Latin Literature and Style by Floyd L. Moreland Rita M. Fleischer revised by Andrew Keller Stephanie Russell Clement Dunbar The Latin/Greek Institute The City University ojNew York Introduction These materials have been prepared to fit the needs of the Summer Latin Institute of Brooklyn College and The City University of New York. and they are structured as an appropriate sequel to Moreland and Fleischer. Latin: An Intensive Course (University of California Press. 1974). However, students can use these materials with equal effectiveness after the completion of any basic grammar text and in any intermediate Latin course whose aim is to introduce students to a variety of authors of both prose and poetry. The materials are especially suited to an intensive or accelerated intermediate course. The authors firmly believe that, upon completion of a basic introduction to grammar. the only way to learn Latin well is to read as much as possible. A prime obstacle to reading is vocabulary: students spend much energy and time looking up the enormous number of words they do not know. Following the system used by Clyde Pharr in Vergil's Aeneid. Books I-VI (Heath. 1930), this problem is minimized by glossing unfamiliar words on each page oftext. Whether a word is familiar or not has been determined by its occurrence or omission in the formal unit vocabularies of Moreland and Fleischer, Latin: An Intensive Course. Students will need to know the words included in the vocabularies of that text and be acquainted with some of the basic principles of word formation. -

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU 1. Translate this sentence into English: Servābuntne nōs Rōmānī, sī Persae īrātī vēnerint? WILL THE ROMANS SAVE US IF THE ANGRY PERSIANS COME? B1: What kind of conditional is illustrated in that sentence? FUTURE MORE VIVID B2: Now translate this sentence into English: Haec nōn loquerēris nisi tam stultus essēs. YOU WOULD NOT SAY THESE THINGS IF YOU WERE NOT SO STUPID TU 2. What versatile author may be the originator of satire, but is more famous for writing fabulae praetextae, fabulae palliatae, and the Annales? (QUINTUS) ENNIUS B1: What silver age author remarked that Ennius had three hearts on account of his trilingualism? AULUS GELLIUS B2: Give one example either a fabula praetexta or a fabula palliata of Ennius. AMBRACIA, CAUPUNCULA, PANCRATIASTES TU 3. What modern slang word, deriving from the Latin word for “four,” is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “crew, posse, gang; an informal group of individuals with a common identity and a sense of solidarity”? SQUAD B1: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “bend”, means “subtly or not-so-subtly showing off your accomplishments or possessions”? FLEX B2: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “end” and defined by the Urban Dictionary as “a word that modern teens and preteens say even though they have absolutely no idea what it really means,” roughly means “getting around issues or problems in a slick or easy way”? FINESSE TU 4. Who elevated his son Diadumenianus to the rank of Caesar when he became emperor in 217 A.D.? MACRINUS B1: Where did Macrinus arrange for the assisination of Caracalla? CARRHAE/EDESSA B2: What was the name of the person who actually did the stabbing of Caracalla? JULIUS MARTIALIS TU 5. -

Roman Domestic Religion : a Study of the Roman Lararia

ROMAN DOMESTIC RELIGION : A STUDY OF THE ROMAN LARARIA by David Gerald Orr Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts 1969 .':J • APPROVAL SHEET Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia Name of Candidate: David Gerald Orr Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis and Abstract Approved: UJ~ ~ J~· Wilhelmina F. {Ashemski Professor History Department Date Approved: '-»( 7 ~ 'ii, Ii (, J ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Roman Domestic Religion: A Study of the Roman Lararia David Gerald Orr, Master of Arts, 1969 Thesis directed by: Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Professor This study summarizes the existing information on the Roman domestic cult and illustrates it by a study of the arch eological evidence. The household shrines (lararia) of Pompeii are discussed in detail. Lararia from other parts of the Roman world are also studied. The domestic worship of the Lares, Vesta, and the Penates, is discussed and their evolution is described. The Lares, protective spirits of the household, were originally rural deities. However, the word Lares was used in many dif ferent connotations apart from domestic religion. Vesta was closely associated with the family hearth and was an ancient agrarian deity. The Penates, whose origins are largely un known, were probably the guardian spirits of the household storeroom. All of the above elements of Roman domestic worship are present in the lararia of Pompeii. The Genius was the living force of a man and was an important element in domestic religion. -

The Poems of Dracontius in Their Vandalic and Visigothic Contexts

The Poems of Dracontius in their Vandalic and Visigothic Contexts Mark Lewis Tizzoni Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The University of Leeds, Institute for Medieval Studies September 2012 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2012 The University of Leeds and Mark Lewis Tizzoni The right of Mark Lewis Tizzoni to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements: There are a great many people to whom I am indebted in the researching and writing of this thesis. Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors: Prof. Ian Wood for his invaluable advice throughout the course of this project and his help with all of the historical and Late Antique aspects of the study and Mr. Ian Moxon, who patiently helped me to work through Dracontius' Latin and prosody, kept me rooted in the Classics, and was always willing to lend an ear. Their encouragement, experience and advice have been not only a great help, but an inspiration. I would also like to thank my advising tutor, Dr. William Flynn for his help in the early stages of the thesis, especially for his advice on liturgy and Latin, and also for helping to secure me the Latin teaching job which allowed me to have a roof over my head.