Common Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Mann Im Schatten Seine Ämter Haben Inzwischen Andere, Seine Macht Haben Sie Nicht

Deutschland CDU Der Mann im Schatten Seine Ämter haben inzwischen andere, seine Macht haben sie nicht. Plant Wolfgang Schäuble ein Comeback? Von Tina Hildebrandt nichtsnutzige Zeitgenossen geisti- ge Überlegenheit spüren zu las- sen, haben seit jeher Distanz zwi- schen Schäuble und seiner Umge- bung geschaffen. Herrisch, kalt, fast unmensch- lich in seiner Kontrolliertheit fan- den und finden ihn viele. In der Fraktion, die er acht Jahre lang streng geführt hat, sowieso. Auch in seinem eigenen Landesverband Baden-Württemberg war Schäuble nie unumstritten. Seit seinem putschartigen Sturz vom Chefsessel der CDU ver- größert ein kollektives schlechtes Gewissen die Distanz. In der Frak- tion sitzt Schäuble hinten links bei seiner Landesgruppe, im Plenum des Bundestags in der zweiten Reihe. Ein Denkmal der Disziplin, das die so genannten Spitzenkräf- te in der ersten Reihe durch bloße Anwesenheit deklassiert und alle anderen daran erinnert, dass sie einen erfolgreichen Parteichef dem Rechtsbrecher Helmut Kohl STEFFEN SCHMIDT / AP SCHMIDT STEFFEN geopfert haben. CDU-Politiker Schäuble: „Ich beschäftige mich nicht mit Posten“ Schäuble weiß das alles. Er hat oft unter dieser Distanz gelitten. ie Hände senken sich auf das Ge- sagt, „können mich das überhaupt nicht Umso mehr genießt er die Wertschätzung, sicht wie ein Vorhang auf die Büh- fragen. Fragen können mich nur die Vor- die ihm nun von Parteifreunden wie dem Dne. Blaue Augen spähen belustigt sitzenden von CDU und CSU.“ sächsischen Premier Kurt Biedenkopf, dem zwischen den Fingern hervor, dann lässt Anderthalb Jahre ist es her, dass sie ihn Thüringer Bernhard Vogel oder dem CSU- Wolfgang Schäuble ein mildes Grinsen se- als Partei- und Fraktionschef verjagt ha- Mann Michael Glos entgegengebracht hen. -

Klausurtagungen U. Gäste CSU-Landesgr

Gäste der CSU-Landesgruppe - Klausurtagungen in Wildbad Kreuth und Kloster Seeon Kloster Seeon (II) 04.01. – 06.01.2018 Greg Clark (Britischer Minister für Wirtschaft, Energie und Industriestrategie) Vitali Klitschko (Bürgermeister von Kiew und Vorsitzender der Regierungspartei „Block Poroshenko“) Frank Thelen (Gründer und Geschäftsführer von Freigeist Capital) Dr. Mathias Döpfner (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Axel Springer SE und Präsident des Bundesverbandes Deutscher Zeitungsverleger) Michael Kretschmer (Ministerpräsident des Freistaates Sachsen) Kloster Seeon (I) 04.01. – 06.01.2017 Erna Solberg (Ministerpräsidentin von Norwegen und Vorsitzende der konservativen Partei Høyre) Julian King (EU-Kommissar für die Sicherheitsunion) Fabrice Leggeri (Exekutive Direktor EU-Grenzschutzagentur FRONTEX) Dr. Bruno Kahl (Präsident des Bundesnachrichtendienstes) Prof. Dr. Heinrich Bedford-Strohm (Landesbischof von Bayern und Vorsitzender des Rates der EKD) Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert MdB (Präsident des Deutschen Bundestages) Joe Kaeser (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Siemens AG) Wildbad Kreuth XL 06.01. – 08.01.2016 Dr. Angela Merkel MdB David Cameron ( Premierminister des Vereinigten Königreichs) Prof. Peter Neumann ( Politikwissenschaftler) Guido Wolf MdL (Vorsitzender der CDU-Fraktion im Landtag von Baden-Württemberg) Dr. Frank-Jürgen Weise (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Bundesagentur für Arbeit und Leiter des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge) Wildbad Kreuth XXXIX 07.01. – 09.01.2015 Professor Dr. Vittorio Hösl * Günther Oettinger (EU-Kommissar für Digitale Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft) Jens Stoltenberg (Nato-Generalsekretär) Margret Suckale (Präsidentin des Chemiearbeitgeberverbandes) Hans Peter Wollseifer (Präsident des Zentralverbandes des Deutschen Handwerks) Dr. Thomas de Maizière (Bundesminister des Innern) Pawlo Anatolijowytsch Klimkin (Außenminister der Ukraine) Wildbad Kreuth XXXVIII 07.01. – 09.01.2014 Matthias Horx (Gründer und Inhaber des Zukunftsinstituts Horx GmbH, Wien) * S.E. John B. -

UID 1987 Nr. 12, Union in Deutschland

CDU-Informationsdienst Union in Deutschland Bonn, den 2. April 1987 12/87 Heiner Geißler: Brandts Rücktritt ist der Ausdruck einer Führung^ und Programmkrise der SPD % Brandts Rücktritt ist die logische Konse- silt1^ aus der Zerstrittenheit und Richtungslo- HEUTE AKTUELL . gkeit der deutschen Sozialdemokratie. Wegen I .res Anpassungskurses gegenüber den Grünen SBrandt und der SPD nicnt • Debatte zur Dnr - gelungen, eine Regierungserklärung j "tische Alternative in der Opposition aufzu- Unsere Argumente gegen falsche Behauptungen und ,erdlngs ist nicht damit zu rechnen, daß die deut- Tatsachenverdrehungen von s SPD und Grünen, 2u . Sozialdemokraten nach dem Rücktritt Brandts ab Seite 3 . einem Kurs der Konsolidierung finden und einen le Zur Regierungserklärung des dJ rparteilichen Klärungsprozeß herbeiführen wer- pro rarnmat sc Bundeskanzlers gibt es ein M h 8 i hen Aussagen des SPD- „CDU-extra" und eine Bro- Sch heitsflügels um 0skar Lafontaine, Gerhard schüre. undr0der' Erhard EpP'er und Hans-Ulrich Klose Seite 37 . d die personellen Weichenstellungen der letzten ^onate lassen nicht erwarten, daß die SPD den • Öffentlichkeitsarbeit e8 zurück zur Volkspartei des Godesberger Pro- Am 19. April 1967 starb Konrad Adenauer. Aus diesem Anlaß ems finden wird. möchten wir den CDU-Verbän- * Ende der Ära Brandt befindet sich die SPD in den einige Anregungen geben. j em Zustand der Zerrüttung und des Niedergangs. Seite 38/39 6reSSe einer funktionsfani en muR 8 Demokratie • Register '86 sichr 6 SPD Jetzt inre Kräfte darauf konzentrieren, Das Stichwortregister — ein un- tis h'11 der °PP°sition personell und programma- ZU re e entbehrlicher Helfer für alle z£ 8 nerieren. Dieser Prozeß braucht viel UiD-Leser. -

Empfang Beim Bundespräsidenten Mitgliederreise Nach Aachen

Dezember ★ ★ ★ ★ 2 0 13 ★ ★ ★ ★ Vereinigung ehemaliger Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages und des Europäischen Parlaments e. V. Editorial Empfang beim Bundespräsidenten Clemens Schwalbe Informationen Termine Personalien Titelthemen Ingrid Matthäus-Maier Empfang beim Bundespräsidenten Jahreshaupt- versammlung Berlin Mitgliederreise nach Bundespräsident Dr. h. c. Joachim Gauck bei seiner Rede an die Mitglieder der Vereinigung Aachen und Maastricht ©Siegfried Scheffler Mitgliederveranstaltung bei der GIZ in Bonn Mitgliederreise nach Berichte / Erlebtes „Ehemalige“ der Landtage Aachen und Maastricht Europäische Asso ziation Study Group on Germany Deutsch-dänische Beziehungen „Ehemalige“ im Ehrenamt Erlesenes Nachrufe Aktuelles Der Geschäftsführer informiert Die „Ehemaligen“ auf der Freitreppe des Aachener Rathauses vor dem Besuch bei Oberbürgermeister Jubilare Marcel Philipp ©Werner Möller Editorial Informationen it unserer Doppel- Termine ausgabe zum Ende M des Jahres geben wir 6./7. Mai 2014 Jahreshauptversammlung in Berlin diesmal einen Gesamtüber- mit Wahl des Vorstandes blick über die Veranstaltungen, 6. Mai 2014 am Abend: Frühjahrsempfang Ereignisse und Aktivitäten der DPG unserer Vereinigung. Der po- litische Höhepunkt in diesem 26. Juni 2014 am Abend: Sommerfest der DPG Jahr war der Empfang von © Brigitte Prévot 8.-10. Oktober 2014 Mitgliederreise nach Franken 250 Teilnehmern beim Bundes- präsidenten Joachim Gauck im Juni. In der darauf folgenden 47. Kalenderwoche Mitgliederveranstaltung in Bonn Jahreshauptversammlung hatten wir den Vizepräsidenten des Bundestages Dr. Hermann Otto Solms zu Gast, welcher sich in seinem Vortrag mit der Würde und dem Ansehen des Personalien Parlaments auseinandersetzte und dabei auch uns „Ehema- • Anlässlich seines 70. Geburtstages wurde Dr. Wolfgang Weng ligen“ eine wichtige Rolle zusprach. Mittlerweile können wir auf dem Neujahrsempfang der FDP am 06.01.2013 in Gerlin- Dr. -

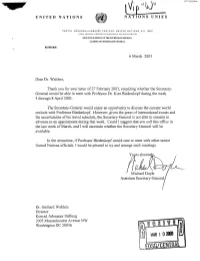

EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POSTAL E: UNITED NATIONS. N. Y 10017 CABLE ADDRESS ADRESSE T E L EG R A P III Q LFE: UNATIONS KEWVOHK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET DU SECRETAIRE GENERAL DEFERENCE 6 March 2003 Dear Dr. Wahlers, Thank you for your letter of 27 February 2003, enquiring whether the Secretary- General would be able to meet with Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf during the week 4 through 8 April 2003. The Secretary-General would enjoy an opportunity to discuss the current world outlook with Professor Biedenkopf. However, given the press of international events and the uncertainties of his travel schedule, the Secretary-General is not able to commit in advance to an appointment during that week. Could I suggest that you call this office in the last week of March, and I will ascertain whether the Secretary-General will be available. In the meantime, if Professor Biedenkopf would care to meet with other senior United Nations officials, I would be pleased to try and arrange such meetings. Yours sincer Michael Doyle Assistant Secretary-General Dr. Gerhard Wahlers Director Konrad Adenauer Stiftung 2005 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20036 EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr. Riza Visit of Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf I hesitate to recommend anything additional for the SG's schedule, given the press of events now and the likelihood that the same pressure will exist in early April. Nonetheless, the SG might find a conversation with this eminent scholar/official interesting and useful. Biedenkopf s knowledge of trans-Atlantic relations is profound. -

„DAS LICHTLEIN IST WEG“ Nur Die Veteranen Unter Den Linksliberalen Intellektuellen Mischen Im Wahlkampf Mit

Intellektuelle „DAS LICHTLEIN IST WEG“ Nur die Veteranen unter den linksliberalen Intellektuellen mischen im Wahlkampf mit. Die jungen Dichter und Denker halten sich heraus – oder denken rechts. Die geringe Unterstützung macht vor allem den Sozialdemokraten zu schaffen. Erst im Fall einer Großen Koalition wollen die Intellektuellen mobilisieren. or diesemAnruferistunterDeutsch- obachtet es der Soziologe Ulrich Beck, Antje Vollmer, die vom Philosophen lands linksliberalen Intellektuellen „eine gewisse Genugtuung, daß die alte Peter Sloterdijk im Kasseler Kampf um Vderzeit niemand sicher: „Hallo, hier gespenstische Schlachtordnung wieder ein Direktmandat für die Grünen unter- spricht der Klaus.“ da ist“. Dafür sorgt die Gespenster- stützt wird, meint, der typische 35jähri- Der Heidelberger Rechtsanwalt und schlacht um die PDS. ge politische Intellektuelle von heute sei Plakatkünstler Klaus Staeck, 56, Wahl- Wo aber sind die Jüngeren, wo ist die entweder Journalist oder Kabarettist. helfer der SPD seit Willy Brandts Zeiten, nächste Generation? Der Berliner „Als Meister der Feder kommentieren telefoniert in diesen Tagen kreuz und Schriftsteller Bodo Morshäuser, 41, sie den Schein des Scheins.“ Politische quer durch die Republik. Wer als Kohl- klagt rechtfertigend über den „schlech- Projekte? Nein, danke. kritisch gilt, wer von Berufs wegen eini- ten Zugang zu den großen Medien“. Er Die alten Kämpen aber, die seit Jahr- germaßen renommiert schauspielert, guckt sich den Wahlkampf leiden- zehnten dabei sind, wirken bei allem musiziert oder schreibt, der hat geringe schaftslos im Fernsehen an. Engagement ausgepowert. „Ich schwim- Chancen, ihm zu entkommen. Staeck will wieder einmal große und wohlklingende Namen für einen Wahl- aufruf zugunsten der SPD sammeln. Rund hundert Prominente, vornweg der Vorsitzende des deutschen Schriftsteller- verbandes Erich Loest, der Rhetorikpro- fessor Walter Jens und der Atomwissen- schaftler Klaus Traube, machen wieder mit. -

Kleine Anfrage

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 12/4569 12. Wahlperiode 11.03.93 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Günter Klein (Bremen), Helmut Sauer (Salzgitter), Claus Jäger, Ulrich Adam, Anneliese Augustin, Richard Bayha, Hans-Dirk Bierling, Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup), Peter Harry Carstensen (Nordstrand), Albert Deß, Anke Eymer, Ilse Falk, Dr. Kurt Faltlhauser, Dr. Karl H. Fell, Leni Fischer (Unna), Herbert Frankenhauser, Erich G. Fritz, Hans-Joachim Fuchtel, Elisabeth Grochtmann, Claus Peter Grotz, Carl-Detlev Freiherr von Hammerstein, Rainer Haungs, Klaus-Jürgen Hedrich, Manfred Heise, Dr. Renate Hellwig, Dr. h. c. Adolf Herkenrath, Ernst Hinsken, Siegfried Hornung, Dr.-Ing. Rainer Jork, Dr. Egon Jüttner, Michael Jung (Limburg), Dr.-Ing. Dietmar Kansy, Peter Kittelmann, Hartmut Koschyk, Thomas Kossendey, Dr. Rudolf Karl Krause (Bonese), Dr.-Ing. Paul Krüger, Dr. Ursula Lehr, Christian Lenzer, Editha Limbach, Theo Magin, Dr. Dietrich Mahlo, Claire Marienfeld, Erwin Marschewski, Dr. Günther Müller, Alfons Müller (Wesseling), Engelbert Nelle, Johannes Nitsch, Friedhelm Ost, Dr. Peter Paziorek, Rolf Rau, Klaus Riegert, Kurt J. (Fürth), Rossmanith, Dr. Christian Ruck, Heribert- Scharrenbroich, Christian Schmidt Dr. Rupert Scholz, Dr. Hermann Schwörer, Michael Stübgen, Dr. Klaus-Dieter Uelhoff, Alois Graf von Waldburg-Zeil, Dr. Roswitha Wisniewski, Simon Wittmann (Tännesberg), Michael Wonneberger, Benno Zierer und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU sowie der Abgeordneten Ulrich Irmer, Dr. Michaela Blunk (Lübeck), Jörg van Essen, Horst Friedrich, Jörg Ganschow, Dr. Sigrid Hoth, Jürgen Koppelin, Dr.-Ing. Karl Hans Laermann, Arno Schmidt (Dresden), Ingrid Walz, Burkhard Zurheide, und der Fraktion der F.D.P. Deutsches Personal bei inter- und supranationalen Organisationen Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland gehört mehr als 200 internatio- nalen Organisationen an und trägt einen erheblichen Teil der Kosten dieser Organisationen. -

Beschlußempfehlung Und Bericht Des Verteidigungsausschusses (12

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 12/3693 12. Wahlperiode 11.11.92 Sachgebiet 53 Beschlußempfehlung und Bericht des Verteidigungsausschusses (12. Ausschuß) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Ulrich Adam, Dr. Walter Franz Altherr, Hans-Dirk Bierling, Paul Breuer, Georg Brunnhuber, Wolfgang Dehnel, Albert Deß, Dr. Kurt Faltlhauser, Hans-Joachim Fuchtel, Johannes Gerster (Mainz), Otto Hauser (Esslingen), Ernst Hinsken, Claus Jäger, Dr. Egon Jüttner, Christian Lenzer, Theo Magin, Dr. Dietrich Mahlo, Claire Marienfeld, Maria Michalk, Dr. Gerhard Päselt, Dr. Friedbert Pflüger, Dr. Bernd Protzner, Heinz Schemken, Graf Joachim von Schönburg-Glauchau, Stefan Schwarz, Heinrich Seesing, Bärbel Sothmann, Karl-Heinz Spilker, Karl Stockhausen, Dr. Klaus-Dieter Uelhoff, Bernd Wilz, Peter Kurt Würzbach, Benno Zierer und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU sowie der Abgeordneten Günther Friedrich Nolting, Dr. Werner Hoyer, Dr. Sigrid Semper, Jürgen Koppelin, Günther Bredehorn, Jörg van Essen, Dr. Cornelia von Teichman, Arno Schmidt (Dresden), Dr. Olaf Feldmann, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, Dr. Wolfgang Weng (Gerlingen) und der Fraktion der F.D.P. — Drucksache 12/1292 — Privatisierung der Heimbetriebsgesellschaft mbH der Bundeswehr A. Problem Die Bundesregierung wird aufgefordert, Maßnahmen zur völligen Privatisierung der Heimbetriebsgesellschaft mbH der Bundeswehr einzuleiten. B. Lösung Annahme des von den Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und F.D.P. aktualisierten Antrages, mit dem die Bundesregierung aufgefor- dert, mit der Privatisierung der Heimbetriebsgesellschaft mbH (HBG) zum 1. Januar 1993 zu beginnen, dabei die Versorgung der Soldaten in entlegenen und kleineren Standorten weiter zu Drucksache 12/3693 Deutscher Bundestag — 12. Wahlperiode gewährleisten und weiterhin ein preisgünstiges Angebot für wehr- dienstleistende Wehrpflichtige sicherzustellen. Mehrheitsentscheidung im Ausschuß C. Alternativen Keine D. Kosten wurden nicht erörtert. Deutscher Bundestag — 12. -

Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 1-2011 Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Kintz, Melanie, "Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006" (2011). Dissertations. 428. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/428 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 by Melanie Kintz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Advisor: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2011 RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation looks at the recruitment patterns to leadership positions in the German Bundestag from 1994 to 2006 with the objective of enhancing understanding of legislative careers and representation theory. Most research on political careers thus far has focused on who is elected to parliament, rather than on which legislators attain leadership positions. However, leadership positions within the parliament often come with special privileges and can serve as stepping stones to higher positions on the executive level. -

19. Oktober 1981: Sitzung Der Landesgruppe

CSU-LG – 9. WP Landesgruppensitzung: 19. 10. 1981 19. Oktober 1981: Sitzung der Landesgruppe ACSP, LG 1981: 15. Überschrift: »Protokoll der 18. Landesgruppensitzung am 19. Oktober 1981«. Zeit: 20.00–20.20 Uhr. Vorsitz: Zimmermann. Anwesend: Althammer, Biehle, Bötsch, Faltlhauser, Fellner, Geiger, Glos, Handlos, Hartmann, Höffkes, Höpfinger, Graf Huyn, Keller, Kiechle, Klein, Kraus, Kunz, Lemmrich, Linsmeier, Niegel, Probst, Regenspurger, Röhner, Rose, Rossmanith, Sauter, Spilker, Spranger, Stücklen, Voss, Warnke, Zierer, Zimmermann. Sitzungsverlauf: A. Bericht des Landesgruppenvorsitzenden Zimmermann über die Bonner Friedensdemonstration vom 10. Oktober 1981, die Haushaltslage, den Deutschlandtag der Jungen Union in Köln, die USA-Reise des CDU-Parteivorsitzenden Kohl und die Herzerkrankung des Bundeskanzlers. B. Erläuterungen des Parlamentarischen Geschäftsführers Röhner zum Plenum der Woche. C. Allgemeine Aussprache. D. Erläuterungen zu dem Gesetzentwurf der CDU/CSU-Fraktion zum Schutze friedfertiger Demonstrationen und Versammlungen. E. Vorbereitung der zweiten und dritten Beratung des von der Bundesregierung eingebrachten Gesetzentwurfs über die Anpassung der Renten der gesetzlichen Rentenversicherung im Jahr 1982 und der zweiten und dritten Beratung des Entwurfs eines Elften Gesetzes über die Anpassung der Leistungen des Bundesversorgungsgesetzes (Elftes Anpassungsgesetz-KOV). [A.] TOP 1: Bericht des Vorsitzenden Dr. Zimmermann begrüßt die Landesgruppe. Er gratuliert den Kollegen Dr. Dollinger, Keller und Hartmann zu ihren Geburtstagen. Dr. Zimmermann betont, daß sich selten die politische Lage in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zwischen zwei Landesgruppensitzungen so verändert habe: Friedensdemonstration1, Haushaltslage und Gesundheit des Kanzlers.2 Drei grundverschiedene Bereiche, von denen jeder allein auf die Koalition destabilisierende Wirkung habe. Was die Haushaltslage angehe, so bedeute eine Lücke von 5 bis 7 Mrd. DM, wie Matthöfer sie für den Haushalt 1982 zugebe, das Ende des vorliegenden Entwurfs.3 1 Zur Friedensdemonstration in Bonn am 10. -

Deutscher Bundestag — 12

Plenarprotokoll 12/76 Deutscher Stenographischer Bericht 76. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 13. Februar 1992 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Vorsitzenden des Obersten (Steueränderungsgesetz 1992) (Drucksa- Rates der Republik Litauen und seiner Dele- chen 12/1108, 12/1368, 12/1466, 12 /1506, gation 6273 A 12/1691, 12/2044) b) Beratung der Beschlußempfehlung des Glückwünsche zu den Geburtstagen der Ausschusses nach Artikel 77 des Grund- Abgeordneten Erika Reinhardt und Dr. gesetzes (Vermittlungsausschuß) zu dem Horst Ehmke 6273B Gesetz zur Aufhebung des Struktur- hilfegesetzes und zur Aufstockung des Namensänderung eines Ausschusses . 6273 B Fonds „Deutsche Einheit" (Drucksachen 12/1227, 12/1374, 12/1494, 12/1692, Nachträgliche Überweisung des 13. Subven- 12/2045) tionsberichts der Bundesregierung an den Hans H. Gattermann FDP . 6274 C Ausschuß für Forschung, Technologie und Technikfolgenabschätzung 6273 B Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble CDU/CSU . 6276A Dr. Peter Struck SPD 6278B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- nung 6273C Dr. Hermann Otto Solms FDP . 6280 C Dr. Barbara Höll PDS/Linke Liste . 6282 A Tagesordnungspunkt 3: Nachwahl eines Mitglieds der Parlamen- Werner Schulz (Berlin) Bündnis 90/GRÜNE 6282 D tarischen Kontrollkommission: Wahlvor- Gerhard Schröder, Ministerpräsident des schlag der Fraktion der CDU/CSU Landes Niedersachsen 6283 C (Drucksache 12/2034) 6273 D Dr. Theodor Waigel, Bundesminister BMF 6285 C Ergebnis der Wahl . 6287 D Namentliche Abstimmung 6287 D Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 2: Beratung des Antrags der Fraktion der Ergebnis -

Liste Deutscher Teilnehmer Bilderberg

• Egon Bahr (1968, 1971, 1982, 1987), German Minister, creator of the Ostpolitik • Rainer Barzel (1966), former German opposition leader • Kurt Biedenkopf (1992), former Prime Minister of Saxony • Max Brauer (1954, 1955, 1958, 1963, 1964, 1966), former Mayor of Hamburg • Birgit Breuel (1973, 1979, 1980, 1991, 1992, 1994), chairwoman of Treuhandanstalt • Andreas von Bülow (1978), former Minister of Research of Germany • Karl Carstens (1971), former President of Germany • Klaus von Dohnanyi (1975, 1977), former Mayor of Hamburg • Ursula Engelen-Kefer (1998), former chairwoman of the German Confederation of Trade Unions • Björn Engholm (1991), former Prime Minister of Schleswig-Holstein • Ludwig Erhard (1966), former Chancellor of Germany • Fritz Erler (1955, 1957, 1958, 1963, 1964, 1966), Socialist Member of Parliament • Joschka Fischer (2008), former Minister of Foreign Affairs (Germany) • Herbert Giersch (1975), Director, Institut fur Weltwirtschaft an der Universitat Kiel • Helmut Haussmann (1979, 1980, 1990, 1996), former Minister of Economics of Germany • Wolfgang Ischinger (1998, 2002, 2008), former German Ambassador to Washington • Helmut Kohl (1980, 1982, 1988), former Chancellor of Germany • Walter Leisler Kiep (1974, 1975, 1977, 1980), former Treasurer of the Christian Democratic Union (Germany) • Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1955, 1957, 1966), former Chancellor of Germany • Hans Klein (1986), Member of German Bundestag • Otto Graf Lambsdorff (1980, 1983, 1984), former Minister of Economics of Germany • Karl Lamers (1995), Member of the