Dawning of a New Era. on the Need to Construct Social Democracy in Europe ERHARD EPPLER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Mann Im Schatten Seine Ämter Haben Inzwischen Andere, Seine Macht Haben Sie Nicht

Deutschland CDU Der Mann im Schatten Seine Ämter haben inzwischen andere, seine Macht haben sie nicht. Plant Wolfgang Schäuble ein Comeback? Von Tina Hildebrandt nichtsnutzige Zeitgenossen geisti- ge Überlegenheit spüren zu las- sen, haben seit jeher Distanz zwi- schen Schäuble und seiner Umge- bung geschaffen. Herrisch, kalt, fast unmensch- lich in seiner Kontrolliertheit fan- den und finden ihn viele. In der Fraktion, die er acht Jahre lang streng geführt hat, sowieso. Auch in seinem eigenen Landesverband Baden-Württemberg war Schäuble nie unumstritten. Seit seinem putschartigen Sturz vom Chefsessel der CDU ver- größert ein kollektives schlechtes Gewissen die Distanz. In der Frak- tion sitzt Schäuble hinten links bei seiner Landesgruppe, im Plenum des Bundestags in der zweiten Reihe. Ein Denkmal der Disziplin, das die so genannten Spitzenkräf- te in der ersten Reihe durch bloße Anwesenheit deklassiert und alle anderen daran erinnert, dass sie einen erfolgreichen Parteichef dem Rechtsbrecher Helmut Kohl STEFFEN SCHMIDT / AP SCHMIDT STEFFEN geopfert haben. CDU-Politiker Schäuble: „Ich beschäftige mich nicht mit Posten“ Schäuble weiß das alles. Er hat oft unter dieser Distanz gelitten. ie Hände senken sich auf das Ge- sagt, „können mich das überhaupt nicht Umso mehr genießt er die Wertschätzung, sicht wie ein Vorhang auf die Büh- fragen. Fragen können mich nur die Vor- die ihm nun von Parteifreunden wie dem Dne. Blaue Augen spähen belustigt sitzenden von CDU und CSU.“ sächsischen Premier Kurt Biedenkopf, dem zwischen den Fingern hervor, dann lässt Anderthalb Jahre ist es her, dass sie ihn Thüringer Bernhard Vogel oder dem CSU- Wolfgang Schäuble ein mildes Grinsen se- als Partei- und Fraktionschef verjagt ha- Mann Michael Glos entgegengebracht hen. -

Klausurtagungen U. Gäste CSU-Landesgr

Gäste der CSU-Landesgruppe - Klausurtagungen in Wildbad Kreuth und Kloster Seeon Kloster Seeon (II) 04.01. – 06.01.2018 Greg Clark (Britischer Minister für Wirtschaft, Energie und Industriestrategie) Vitali Klitschko (Bürgermeister von Kiew und Vorsitzender der Regierungspartei „Block Poroshenko“) Frank Thelen (Gründer und Geschäftsführer von Freigeist Capital) Dr. Mathias Döpfner (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Axel Springer SE und Präsident des Bundesverbandes Deutscher Zeitungsverleger) Michael Kretschmer (Ministerpräsident des Freistaates Sachsen) Kloster Seeon (I) 04.01. – 06.01.2017 Erna Solberg (Ministerpräsidentin von Norwegen und Vorsitzende der konservativen Partei Høyre) Julian King (EU-Kommissar für die Sicherheitsunion) Fabrice Leggeri (Exekutive Direktor EU-Grenzschutzagentur FRONTEX) Dr. Bruno Kahl (Präsident des Bundesnachrichtendienstes) Prof. Dr. Heinrich Bedford-Strohm (Landesbischof von Bayern und Vorsitzender des Rates der EKD) Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert MdB (Präsident des Deutschen Bundestages) Joe Kaeser (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Siemens AG) Wildbad Kreuth XL 06.01. – 08.01.2016 Dr. Angela Merkel MdB David Cameron ( Premierminister des Vereinigten Königreichs) Prof. Peter Neumann ( Politikwissenschaftler) Guido Wolf MdL (Vorsitzender der CDU-Fraktion im Landtag von Baden-Württemberg) Dr. Frank-Jürgen Weise (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Bundesagentur für Arbeit und Leiter des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge) Wildbad Kreuth XXXIX 07.01. – 09.01.2015 Professor Dr. Vittorio Hösl * Günther Oettinger (EU-Kommissar für Digitale Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft) Jens Stoltenberg (Nato-Generalsekretär) Margret Suckale (Präsidentin des Chemiearbeitgeberverbandes) Hans Peter Wollseifer (Präsident des Zentralverbandes des Deutschen Handwerks) Dr. Thomas de Maizière (Bundesminister des Innern) Pawlo Anatolijowytsch Klimkin (Außenminister der Ukraine) Wildbad Kreuth XXXVIII 07.01. – 09.01.2014 Matthias Horx (Gründer und Inhaber des Zukunftsinstituts Horx GmbH, Wien) * S.E. John B. -

Willy Brandt – Stimmen Zum 100. Geburtstag Reden Und Beiträge Im Erinnerungsjahr 2013

Willy Brandt – Stimmen zum 100. Geburtstag Reden und Beiträge im Erinnerungsjahr 2013 Schriftenreihe Heft 27 HERAUSGEBERIN Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Bundesstiftung des öffentlichen Rechts Der Vorstand Karsten Brenner, Ministerialdirektor a.D. (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Dieter Dowe Prof. Dr. Axel Schildt Willy Brandt – Stimmen zum 100. Geburtstag REDAKTION Dr. Wolfram Hoppenstedt (Geschäftsführer) Dr. Bernd Rother Reden und Beiträge im Erinnerungsjahr 2013 Dr. Wolfgang Schmidt Schriftleitung: Dr. Wolfram Hoppenstedt Diese Publikation wurde aus Mitteln des Haushalts der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (BKM) finanziert. © 2014 by Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung Forum Willy Brandt Berlin Willy-Brandt-Haus Lübeck Unter den Linden 62-68 Königstraße 21 D-10117 Berlin D-23552 Lübeck Tel.: 030 / 787707-0 Tel.: 0451 / 122425-0 Fax: 030 / 787707-50 Fax: 0451 / 122425-9 [email protected] [email protected] www.willy-brandt.de www.willy-brandt-luebeck.de GESTALTUNG Pralle Sonne, Berlin REALISATION UND DRUCK Hans Gieselmann Druck und Medienhaus, Nuthetal © Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung d.ö.R. Printed in Germany 2014 ISSN 1434-6176 Schriftenreihe der Bundeskanzler-Willy-Brandt-Stiftung ISBN 978-3-933090-26-3 Heft 27 INHALT Willy Brandt – Stationen seines Lebens 6 Erhard Eppler 8 Willy Brandt zum 100. Geburtstag Jonas Gahr Støre 18 Ein Mann mit zwei Vaterländern Joachim Gauck 21 Bis heute ein Vorbild Heinz Fischer 25 Ein ganzes Leben lang Gutes bewirkt Sigmar Gabriel 32 Er hat den Menschen Hoffnung gegeben Ricardo Nuñez 40 Er hat uns Mut gemacht Björn Engholm 43 Was die Größe von Willy Brandt ausmacht Werner A. Perger 50 Deutscher Weltbürger, nationaler Kosmopolit Wolfgang Thierse 55 Global denken und handeln Peter Brandt 59 Versuch einer Annäherung Interview mit Egon Bahr 74 Frieden und Deutschland miteinander verbunden Karsten Brenner 80 Nachwort Quellenverzeichnis 85 Empfehlungen zum Weiterlesen 87 6 7 WILLY BRANDT – STATIONEN SEINES LEBENS 1913 Am 18. -

Allemansvriend

HOOFDSTUK 1 Allemansvriend Op 29 september 2003 werd Johan Stekelenburg – nog geen 62 jaar oud – gecremeerd na een herdenkingsdienst in de St. Dionysiuskerk in Tilburg. Dominee Eddy Reefhuis leidde de dienst en stelde vast dat het een wonderlijke verzameling mensen was, die zich rondom de baar had verzameld. Familie en vrienden natuurlijk. Vertegenwoordigers van gemeente, provincie en rijksoverheid. Het Koninklijk Huis, het kabinet, alle politieke partijen, het bedrijfsleven, werkgevers- en werknemersorganisaties. Het bisdom, artiesten, de journalistiek en uiteenlopende maatschappelijke organisaties, zoals de Anne Frank Stichting, Brabantse schuttersgilden, het tuberculosefonds, de KNVB. Dominee Eddy Reefhuis: ‘Hoe houd je het urenlang spannend...?’ ‘Typisch zo’n gezelschap zoals Johan Stekelenburg dat bijeen kan krijgen: zo groot, zo divers, zo betrokken. Hij zou er van genoten hebben’, zei Eddy Reefhuis. Meer dan duizend genodigden luisterden naar zijn woorden, zowel ín de kerk als via een directe beeld- en geluidsverbinding naar de schouwburg tegenover de kerk. In de huiskamer werd Eddy Reefhuis door 115.000 mensen gezien en gehoord. TV Brabant zond de herdenkingsdienst rechtstreeks uit en boekte een kijkcijferrecord. Het liefste had Heleen Hoekstra, Johans vrouw, de afscheidsbijeenkomst in de Tilburgse concertzaal gehouden, vooral vanwege het licht. Maar er bleken tal van onoverkomelijke bezwaren. De kist zou via trappetjes en een lift naar binnen gesjord moeten worden. Bovendien hield de kwaliteit van de geluidsinstallatie geen gelijke tred met de akoustiek in de zaal. En dus reisde loco-burgemeester Els Aarts op verzoek van Johan en Heleen naar bisschop Hurkmans in Den Bosch om toestemming te vragen ‘de Heikese kerk’ – zoals Tilburgers de Dionysiuskerk noemen – te mogen gebruiken voor de herdenkingsdienst van een socialist. -

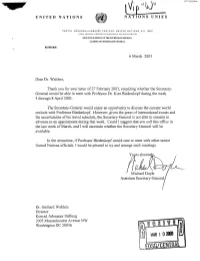

EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POSTAL E: UNITED NATIONS. N. Y 10017 CABLE ADDRESS ADRESSE T E L EG R A P III Q LFE: UNATIONS KEWVOHK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET DU SECRETAIRE GENERAL DEFERENCE 6 March 2003 Dear Dr. Wahlers, Thank you for your letter of 27 February 2003, enquiring whether the Secretary- General would be able to meet with Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf during the week 4 through 8 April 2003. The Secretary-General would enjoy an opportunity to discuss the current world outlook with Professor Biedenkopf. However, given the press of international events and the uncertainties of his travel schedule, the Secretary-General is not able to commit in advance to an appointment during that week. Could I suggest that you call this office in the last week of March, and I will ascertain whether the Secretary-General will be available. In the meantime, if Professor Biedenkopf would care to meet with other senior United Nations officials, I would be pleased to try and arrange such meetings. Yours sincer Michael Doyle Assistant Secretary-General Dr. Gerhard Wahlers Director Konrad Adenauer Stiftung 2005 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20036 EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr. Riza Visit of Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf I hesitate to recommend anything additional for the SG's schedule, given the press of events now and the likelihood that the same pressure will exist in early April. Nonetheless, the SG might find a conversation with this eminent scholar/official interesting and useful. Biedenkopf s knowledge of trans-Atlantic relations is profound. -

"Overweldigend Nee Tegen Europese Grondwet" in <I>De Volkskrant</I

"Overweldigend nee tegen Europese Grondwet" in De Volkskrant (2 juni 2005) Source: De Volkskrant. 02.06.2005. Amsterdam. Copyright: (c) de Volkskrant bv URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/"overweldigend_nee_tegen_europese_grondwet"_in_de_volkskrant_2_juni_2005-nl- b40c7b58-b110-4b79-b92a-faf4da2bc4e0.html Publication date: 19/09/2012 1 / 3 19/09/2012 Overweldigend nee tegen Europese Grondwet Van onze verslaggevers DEN HAAG/ BRUSSEL - Een overgrote meerderheid (bijna 62 procent) van de Nederlandse kiezers heeft de Europese Grondwet afgewezen. Premier Balkenende zei woensdagavond dat hij ‘zeer teleurgesteld’ is. Maar het kabinet ‘zal de uitslag respecteren en rechtdoen’. Balkenende: ‘Nee is nee. Wij begrijpen de zorgen. Over het verlies aan soevereiniteit, over het tempo van de veranderingen in Europa zonder dat de burgers zich daarbij betrokken voelen, over onze financiële bijdrage aan Brussel. En daar moet in Europa rekening mee worden gehouden’. De premier beloofde deze punten aan te snijden tijdens de Europese topconferentie later deze maand in Brussel. De Tweede Kamer zal vandaag het kabinet vragen om het voorstel tot goedkeuring van de Grondwet in te trekken. Balkenende en vice-premier Gerrit Zalm (VVD) gaven aan dat ze dat zullen doen. Nederland is na Frankrijk het tweede land dat de Grondwet afwijst. In Frankrijk stemde 55 procent van de bevolking tegen de Grondwet. In Nederland blijkt zelfs 61,6 procent van de kiezers tegen; 38,4 procent stemde voor. De opkomst was met 62,8 procent onverwacht hoog. Bij de laatste Europese verkiezingen in Nederland kwam slechts 39,1 procent van de stemgerechtigden op. In Brussel werd woensdag met teleurstelling gereageerd. De Luxemburgse premier Jean-Claude Juncker, dienstdoend voorzitter van de EU, verwacht niettemin dat de Europese leiders deze maand zullen besluiten om het proces van ratificatie (goedkeuring) van de Grondwet in alle 25 lidstaten voort te zetten. -

Searching the News 1 Introduction

Searching the news Using a rich ontology with time-bound roles to search through annotated newspaper archives Wouter van Atteveldt1, Nel Ruigrok2, Stefan Schlobach1, and Frank van Harmelen1 1 Department of Arti¯cial Intelligence Free University Amsterdam De Boelelaan 1071, 1071 HV Amsterdam fwva,schlobac,[email protected] 2 The Netherlands News Monitor University of Amsterdam Kloveniersburgwal 48, 1012 CX Amsterdam [email protected] Abstract. A frequent motivation for annotating documents using ontologies is to allow more e±cient search. For collections of newspaper articles, it is often di±cult to ¯nd spe- ci¯c articles based on keywords or topics alone. This paper describes a system that uses a formalisation of the content of newspaper articles to answer complex queries. The data for this system is created using Relational Content Analysis, a method used in Communication Sciences in which documents are annotated using a rich annotation scheme based on an on- tology that includes political roles with temporal validity. Using custom inferencing over the temporal relations and query translation, our system can be used to search for and browse through newspaper articles and to perform systematic analyses by evaluating queries against all articles in the corpus. This makes the system useful both for the (Social) Scientist and for interested laypersons. 1 Introduction A number of services exist that o®er keyword-based search of news content, such as Google news3 and LexisNexis4. Such services have severe limitations, however. The ¯rst di±culty is the semantic gap between keywords and meaning that is always present in keyword based search. -

Politiek Is Vechten'

'Politiek is vechten' Mariëtte Hamer voert volgende week, na Verantwoordingsdag, haar eerste debat als PvdA-fractievoorzitter in de Tweede Kamer. Ze heeft het medicijn gevonden voor haar kwakkelende partij: strijd. Tot op de grond staan de bossen bloemen in haar werkvertrek. "En dit is de helft, hoor", lacht Mariëtte Hamer: "Thuis staan er nog een stuk of tien." Het is donderdagochtend 24 april, anderhalve dag na haar verkiezing tot fractievoorzitter. Een stemming die ze, volgens velen, nipt won van gewezen milieuactivist Diederik Samsom. Hamer was verrast door zijn tegenkandidatuur: "Omdat we beiden lid waren van een heel close team, dacht ik wel even: oh? Maar zoals Diederik voluit zijn verlies nam, dat vond ik top." Nu staat Hamer op het punt naar een familiehuisje in Frankrijk te vertrekken, voor de broodnodige rust na vier hectische maanden als vervangster van de door hartproblemen getroffen Jacques Tichelaar. Maar, benadrukt ze, wat ze vooral gaat doen ("in zo'n Hans en Grietje-huisje op een berg in de Ardèche") is nadenken over de toekomst, over haar nieuwe functie, over de partij, over het kabinet. Half mei is ze terug, dan zal ze de eerste contouren van "de agenda van Mariëtte Hamer" ontvouwen. Want ze mag het schip de afgelopen maanden aardig op koers hebben gehouden, nu staat ze echt aan het roer. En goede roergangers kan de PvdA gebruiken. Na ruim een jaar regeren zitten de sociaal-democraten in zwaar weer. De peilingen zijn slecht, PvdA-successen worden moeizaam verkocht, incidenten volgen elkaar op. De affaire rond oud-minister Herfkens, de problemen bij de wijkenaanpak van minister Vogelaar en haar optreden in de media, de aanhoudende kritiek op het 'softe' leiderschap van vicepremier en partijleider Wouter Bos, intern geruzie over integratie en islam. -

Neue Regierung in Den Niederlanden

Europabüro · European Office · Bureau Européen Neue Regierung in den Niederlanden Dr. Peter Weilemann / Melanie Frank Februar 2007 Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Europabüro, Avenue de l’Yser 11, B-1040 Bruxelles ( +32-2-743.07.43 2 +32-2-743.07.49 : [email protected] : http://www.kas.de -2- Nach langwierigen und beschwerlichen Verhandlungen haben sich der CDA (Christen Democratisch Appel), ChristenUnie und sozialdemokratische PvdA in den Niederlanden auf ein Regierungsprogramm verständigt. Jan Peter Balkenende (CDA) wird auch weiterhin den Ministerpräsidenten stellen. Die Parteivorsitzenden Wouter Bos (PvdA) und André Rouvoet (ChristenUnie) werden Teil des neuen Kabinetts: Vize-Ministerpräsident Bos soll das Finanzministerium übertragen werden und Rouvoet soll als Vize-Ministerpräsident das neu eingerichtete Ressort Jugend und Familie übernehmen. Vor den Wahlen hatten nur 4% der niederländischen Bevölkerung dieser Regierungskonstellation den Vorzug gegeben, doch nun stehen 64% der Bevölkerung laut Umfrage dieser Koalition wohlwollend gegenüber. Das Motto der neuen Regierung lautet „zusammen arbeiten, zusammen leben“ (samen werken, samen leven). Dieses Motto bringe zum Ausdruck, dass die Koalition ihre gemeinsame Arbeit durch Respekt, Solidarität und Dauerhaftigkeit kennzeichnet, so Balkenende. Die CDA-Fraktion stimmte mit großem Enthusiasmus für die Regierungsvereinbarung. Balkenende betonte, dass die Fraktion sehr von dem Ergebnis eingenommen sei und eine enorme Motivation an den Tag gelegt hatte. Nach Ansicht interner Kreise hatte der sogenannte „Formateur“ Herman Wijffels (CDA) entscheidenden Anteil an dem schnellen Abschluss der Gespräche. Das am vergangenen Mittwoch vorgestellte Ergebnis der Verhandlungen ist auf sechs „Pfeilern“ aufgebaut: Zunächst „internationale und europäische Angelegenheiten“, dann „Innovation“ sowie als drittes „Wettbewerb und Unternehmertum“. Zentrale Themen sind viertens „sozialer Zusammenhalt“ und fünftens „Soziales“. -

Introduction: the Nuclear Crisis, NATO's Double-Track Decision

Introduction Th e Nuclear Crisis, NATO’s Double-Track Decision, and the Peace Movement of the 1980s Christoph Becker-Schaum, Philipp Gassert, Martin Klimke, Wilfried Mausbach, and Marianne Zepp In the fall of 1983 more than a million people all across West Germany gathered under the motto “No to Nuclear Armament” to protest the imple- mentation of NATO’s Double-Track Decision of 12 December 1979 and the resulting deployment of Pershing II and cruise missiles in West Germany and other European countries.1 Th e media overfl owed with photos of human chains, sit-in blockades, and enormous protest rallies. Th e impressive range of protest events included street theater performances, protest marches, and blockades of missile depots. During the fi nal days of the campaign there were huge mass protests with several hundred thousand participants, such as the “Fall Action Week 1983” in Bonn on 22 October and a human chain stretching about 108 km from Ulm to Stuttgart. It seemed as if “peace” was the dominant theme all over Germany.2 Despite these protests, the West German Bundestag approved the missile deployment with the votes of the governing conservative coalition, thereby concluding one of the longest debates in German parliamentary history.3 A few days later the fi rst of the so-called Euromissiles were installed in Mut- langen, near Stuttgart, and in Sigonella, on the island of Sicily.4 Th e peace movement had failed to attain its short-term political aim. However, after a brief period of refl ection, the movement continued to mobilize masses of people for its political peace agenda. -

Argos, De Ochtenden, VPRO, Radio 1, Vrijdag 17 Februari 2006 Tweede

Argos, De Ochtenden, VPRO, Radio 1, vrijdag 17 februari 2006 Tweede Kamer buitenspel door vertrouwelijke informatie? xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Aankondigingstekst voor kranten: Vier fractievoorzitters in de Tweede Kamer vertellen in Argos over een parlementair dilemma, Maxime Verhagen (CDA), Wouter Bos (PvdA), Jan Marijnissen (SP) en Femke Halsema (Groen Links). Hoe gaan zij om met vertrouwelijke informatie die ze van de regering krijgen? Hoe verhoudt de geheimhouding zich tot de taak van het parlement om de regering in het openbaar te controleren? Zijn er verschillen tussen een regeringspartij en de oppositie? Ter rechtvaardiging van geheimhouding worden vaak veiligheidsbelangen opgevoerd; maar zijn dat ook de werkelijke redenen? Of gebruikt de regering vertrouwelijkheid ook om het parlementaire debat bij lastige kwesties te omzeilen en de oppositie de mond te snoeren? Argos over omstreden militaire operaties, die ook jaren na dato nog steeds als staatsgeheim worden behandeld. Over het wegmoffelen van de doodsoorzaken van teruggestuurde asielzoekers. En over de Commissie Stiekem van de Tweede Kamer, die het functioneren van de inlichtingendiensten moet controleren. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Aankondiging uitzending door VPRO-presentator: Fractieleiders of fractiespecialisten uit de Tweede Kamer, die vertrouwelijk worden geïnformeerd door de regering maar er vervolgens niets over mogen zeggen. Dat is allang geen uitzondering meer. Zeker nu de Kamer steeds vaker discussieert over onderwerpen als terreurbestrijding en buitenlandse militaire missies. Maar kan het parlement de regering dan nog wel goed controleren? Femke Halsema Ik herinner me die weken als extreem frustrerend. Omdat je het gevoel had dat je informatie bezat die van belang was voor de veiligheid van mensen en daar niets mee kon doen. -

Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 1-2011 Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Kintz, Melanie, "Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006" (2011). Dissertations. 428. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/428 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 by Melanie Kintz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Advisor: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2011 RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation looks at the recruitment patterns to leadership positions in the German Bundestag from 1994 to 2006 with the objective of enhancing understanding of legislative careers and representation theory. Most research on political careers thus far has focused on who is elected to parliament, rather than on which legislators attain leadership positions. However, leadership positions within the parliament often come with special privileges and can serve as stepping stones to higher positions on the executive level.