Analysis of Comments for Telugu Script LGR Proposal for the Root Zone Revision: June 30, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

75 Characters Maximum

Kannada Script LGR Proposal Introduction, Current Analysis and Next Steps Dr. U.B. Pavanaja NBGP F2F Meeting, Colombo 14 December 2017 | 1 Agenda 1 2 3 Introduction to Repertoire Analysis Within Script Kannada Script Variants 4 5 6 Cross-Script WLE Rules Current Status and Variants Next Steps for Completion | 2 Introduction to Kannada Script Population – there are about 60 million speakers of Kannada language which uses Kannada script. Geographical area - Kannada is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad Languages written in Kannada script – Kannada, Tulu, Kodava (Coorgi), Konkani, Havyaka, Sanketi, Beary (byaari), Arebaase, Koraga | 3 Classification of Characters Swaras (vowels) Letter ಅ ಆ ಇ ಈ ಉ ಊ ಋ ಎ ಏ ಐ ಒ ಓ ಔ Vowel sign/ N/Aಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ matra Yogavahas In Kannada, all consonants Anusvara ಅಂ (vyanjanas) when written as ಕ (ka), ಖ (kha), ಗ (ga), etc. actually have a built-in vowel sign (matra) Visarga ಅಃ of vowel ಅ (a) in them. | 4 Classification of Characters Vargeeya vyanjana (structured consonants) voiceless voiceless aspirate voiced voiced aspirate nasal Velars ಕ ಖ ಗ ಘ ಙ Palatals ಚ ಛ ಜ ಝ ಞ Retroflex ಟ ಠ ಡ ಢ ಣ Dentals ತ ಥ ದ ಧ ನ Labials ಪ ಫ ಬ ಭ ಮ Avargeeya vyanjana (unstructured consonants) ಯ ರ ಱ (obsolete) ಲ ವ ಶ ಷ ಸ ಹ ಳ ೞ (obsolete) | 5 Repertoire Included-1 Sr. Unicode Glyph Character Name Unicode Indic Ref Widespread No. Code General Syllabic use ? Point Category Category [Yes/No] 1 0C82 ಂ KANNADA SIGN ANUSVARA Mc Anusvara Yes 2 0C83 ಂ KANNADA SIGN VISARGA Mc Visarga Yes 3 0C85 ಅ KANNADA LETTER A Lo Vowel Yes 4 0C86 ಆ KANNADA LETTER AA Lo Vowel Yes 5 0C87 ಇ KANNADA LETTER I Lo Vowel Yes 6 0C88 ಈ KANNADA LETTER II Lo Vowel Yes 7 0C89 ಉ KANNADA LETTER U Lo Vowel Yes 8 0C8A ಊ KANNADA LETTER UU Lo Vowel Yes KANNADA LETTER VOCALIC 9 0C8B ಋ R Lo Vowel Yes 10 0C8E ಎ KANNADA LETTER E Lo Vowel Yes | 6 Repertoire Included-2 Sr. -

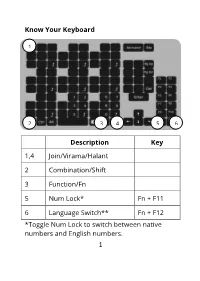

Know Your Keyboard Description Key 1,4 Join/Virama/Halant 2

Know Your Keyboard 1 2 3 4 5 6 Description Key 1,4 Join/Virama/Halant 2 Combination/Shift 3 Function/Fn 5 Num Lock* Fn + F11 6 Language Switch** Fn + F12 *Toggle Num Lock to switch between native numbers and English numbers. 1 ** Language Switch works on Windows, Linux and Android. For macOS, a configuration in settings is required. Note: If numbers are appearing in English, turn off Num Lock. Connecting Your Keyboard To Computer – Plug-in the cable to USB port on your computer. To Android Phone/Tablet 3 2 1 Use USB-to-OTG connector to plug-in keyboard. 2 Language and Layout You can use one keyboard to type multiple languages. You need to install at least one language to type. Language Layout Bengali Ka-Naada Bengali Keyboard Assamese Devanagari Sanskrit Hindi Ka-Naada Hindi Keyboard Marathi Neapli English Ka-Naada English Keyboard Guajarati Ka-Naada Guajarati Keyboard Kannada Ka-Naada Kannada Keyboard Malayalam Ka-Naada Malayalam Keyboard Tulu Odiya Ka-Naada Odiya Keyboard Panjabi Ka-Naada Gurmukhi Keyboard Telugu Ka-Naada Telugu Keyboard 3 Note: You need to switch to Ka-Naada input language before typing. Note: To switch between the languages you’re using, repeatedly press Language Switch key to cycle through all your installed languages. Language Pack Installation Go to https://ka-naada.com/downloads/ and click on the “Download” button in front of your operating system. Installation – Windows 1. Open your “Downloads” folder and locate “kanaada_keyboards.zip”. 2. Right click on zip file and choose “Extract Here” from the option menu. 3. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

N4185 Preliminary Proposal to Encode Siddham in ISO/IEC 10646

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4185 L2/12-011R 2012-05-03 Preliminary Proposal to Encode Siddham in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey Department of History University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. [email protected] May 3, 2012 1 Introduction This is a preliminary proposal to encode the Siddham script in the Universal Character Set (ISO/IEC 10646). It is a collaborative effort between the Script Encoding Initiative (SEI) at the University of California, Berke- ley and the Shingon Buddhist International Institute, Fresno, California. Feedback is requested from experts and users of the script. Comments may be submitted to the author at the email address given above. Siddham is a Brahmi-based writing system that originated in India, but which is used primarily in East Asia. At present it is associated with esoteric Buddhist traditions in Japan. Nevertheless, Siddham is structurally an Indic script and its proposed encoding adheres to the UCS model for Brahmi-based writing systems, such as Devanagari and similar scripts. The technical description for Siddham given here may differ from the traditional analysis and philosophical interpretations of the script and its constituent characters and glyphs. An attempt has been made to encode all distinct characters attested in Siddham records, although more characters may be uncovered through additional research. The characters that are proposed for encoding have been analyzed in accordance with the character-glyph model of the UCS. As a result, the proposed encoding may contain characters that are not part of traditional character repertoires. It may also exclude characters that are traditionally regarded as independent letters, such as conjuncts, which are to be represented in the manner specified by the UCS encoding model. -

A Barrier to Indic-Language Implementation of Unicode Is the Perception That Encoding Order in Unicode Is Equivalent to Lingui

Issues in Indic Language Collation Issues in Indic Language Collation Cathy Wissink Program Manager, Windows Globalization Microsoft Corporation I. Introduction As the software market for India1 grows, so does the interest in developing products for this market, and Unicode is part of many vendors’ solutions. However, many software vendors see a barrier to implementing Unicode on products for the Indic-language market. This barrier is the perception that deficiencies in Unicode will keep software developers from creating products that are culturally and linguistically appropriate for the Indian market. This perception manifests itself in a number of ways, but one major concern that the Indic language community has voiced is the fact that the Unicode character encoding order is not appropriate for linguistic collation (or sorting). This belief that character encoding order in Unicode must be equivalent to linguistic collation of these same scripts and their respective languages is considered by some developers a blocking point to adoption of Unicode in the Indian market, and is indicative of the greater concern within the Indic-language community about the feasibility of Unicode for their scripts. This paper will demonstrate that this perceived barrier to Unicode adoption does not exist and that it is possible to provide properly globalized software for the Indic market with the current implementation of Unicode, using the example of Indic language collation. A brief history of Indic encodings will be given to set the stage for the current mentality regarding Unicode in the Indian market. The basics of linguistic collation and its application to Indic scripts will then be discussed, compared to encoding, and demonstrated as it exists on Windows XP. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

Proposal to Annotate Brahmi Sign Anusvara Vinodh Rajan [email protected] Shriramana Sharma [email protected]

P a g e | 1 Proposal to Annotate Brahmi Sign Anusvara Vinodh Rajan [email protected] Shriramana Sharma [email protected] 1 Introduction L2/19-402 initially proposed the addition of 6 Old Tamil characters to the Brahmi block, out of which 5 were accepted by the UTC #162 in January 2020. The dot-shaped Old Tamil Virama was not accepted due to the block already having another dot-shaped character i.e. U+11001 the Brahmi Anusvara character, which could possibly be repurposed to represent the Old Tamil Virama. It was also suggested to reconsider the unification with the existing Virama character. This document proposes the unification of the Brahmi Anusvara and the Old Tamil Virama and requests that the existing Brahmi Anusvara character be annotated for its additional usage as the Tamil-Brahmi Virama. 2 Positioning of Brahmi Anusvara and Tamil-Brahmi Virama The Brahmi Anusvara is a dot-shaped character usually placed at the top-right position. However, it may also be placed at the top or even at the bottom-right position. Below shown are examples from Indoskript1 for occurrences of the following syllables - /aṃ/, /khaṃ/, /kiṃ/, /tuṃ/ & /luṃ/ - between 300 BCE and 100 CE. 1 http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/falk/ P a g e | 2 Old Tamil Virama is also a dot-shaped character, which can occur in multiple positions. From Early Tamil Epigraphy by Iravatham Mahadevan https://www.cmi.ac.in/gift/Epigraphy/epig_vikramangalam_not%20considered.htm Standardized representation of Tamil in recent books also shows variation in positioning: http://know-your-heritage.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_14.html Old Tamil Virama occurring at the top position P a g e | 3 https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2018/dec/12/this-is-how-thiruvalluvar-wrote- thirukkural-couplets-1910278.html Old Tamil Virama occurring to the left As it can been seen, both the Anusvara and the Old Tamil Virama are dot-shaped characters with variable positioning. -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions. -

Initial Literacy in Devanagari: What Matters to Learners

Initial literacy in Devanagari: What Matters to Learners Renu Gupta University of Aizu 1. Introduction Heritage language instruction is on the rise at universities in the US, presenting a new set of challenges for language pedagogy. Since heritage language learners have some experience of the target language from their home environment, language instruction cannot be modeled on foreign language instruction (Kondo-Brown, 2003). At the same time, there may be significant gaps in the learner’s competence; in describing heritage learners of South Asian languages, Moag (1996) notes that their acquisition of the native language has often atrophied at an early stage. For learners of South Asian languages, the writing system presents an additional hurdle. Moag (1996) states that heritage learners have more problems than their American counterparts in learning the script; the heritage learner “typically takes much more time to master the script, and persists in having problems with both reading and writing far longer than his or her American counterpart” (page 170). Moag attributes this to the different purposes for which learners study the language, arguing that non-native speakers rapidly learn the script since they study the language for professional purposes, whereas heritage learners study it for personal reasons. Although many heritage languages, such as Japanese, Mandarin, and the South Asian languages, use writing systems that differ from English, the difficulties of learning a second writing system have received little attention. At the elementary school level, Perez (2004) has summarized differences in writing systems and rhetorical structures, while Sassoon (1995) has documented the problems of school children learning English as a second script; in addition, Cook and Bassetti (2005) offer research studies on the acquisition of some writing systems. -

MSR-4: Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK

Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4 Annotated Repertoire Tables, Non-CJK Integration Panel Date: 2019-01-25 How to read this file: This file shows all non-CJK characters that are included in the MSR-4 with a yellow background. The set of these code points matches the repertoire specified in the XML format of the MSR. Where present, annotations on individual code points indicate some or all of the languages a code point is used for. This file lists only those Unicode blocks containing non-CJK code points included in the MSR. Code points listed in this document, which are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR for various reasons are shown with pinkish annotations indicating the primary rationale for excluding the code points, together with other information about usage background, where present. Code points shown with a white background are not PVALID in IDNA2008. Repertoire corresponding to the CJK Unified Ideographs: Main (4E00-9FFF), Extension-A (3400-4DBF), Extension B (20000- 2A6DF), and Hangul Syllables (AC00-D7A3) are included in separate files. For links to these files see "Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale". How the repertoire was chosen: This file only provides a brief categorization of code points that are PVALID in IDNA2008 but excluded from the MSR. For a complete discussion of the principles and guidelines followed by the Integration Panel in creating the MSR, as well as links to the other files, please see “Maximal Starting Repertoire - MSR-4: Overview and Rationale”. Brief description of exclusion -

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2827 Proposal of 4 Myanmar Semivowels - Page: 1/13 Version: 22-Jun-04 8:23 AM

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2827 Proposal of 4 Myanmar semivowels - page: 1/13 Version: 22-Jun-04 8:23 AM Title: Proposal of 4 Myanmar Semivowels Source: Myanmar Unicode and NLP Research Center Status: National Contribution Action: For consideration by WG2 Date: 21-June-2004 This document requests additional characters to be added to the UCS within Myanmar block. It also requests to pull 4 semivowel signs out of virama model. This contains the proposal summary form. A. Administrative 1. Title Proposal of 4 Myanmar semivowels 2. Requester’s name Myanmar Unicode & NLP Research Center 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution) National contribution. 4. Submission date 2004-06-21 5. Requester’s reference (if applicable) Thein OO, President, MCF <[email protected]> Thein HTUT, Secretary, MCSA Tun TINT, Member, Myanmar Language Commission Zaw HTUT, Program Manager, Myanmar UNLP Research Center <[email protected]> Ngwe TUN, Program Manager, Myanmar UNLP Research Center <[email protected]> c/o: MYANMAR UNICODE AND NLP RESEARCH CENTER Myanmar Computer Federation B1R1, Myanmar ICT Park, Universities' Hlaing Campus, 11052, Yangon, Myanmar Tel: +95-1-652307 eFax: +1-707-988-0300 Email: [email protected] , [email protected] Internet: http://www.mcf.org.mm , http://myanmars.net/unicode/ 6. Choose one of the following: 6a. This is a complete proposal Yes. 6b. More information will be provided later No. B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: 1a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters) No. Proposed name of script 1b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block Yes.