Spotlaw 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001 Presented Below Is an Alphabetical Abstract of Languages A

Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Census 2001 STATEMENT 1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2001 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 122 languages and 234 mother tongues. The 22 languages PART A - Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages) Name of language and Number of persons who returned the Name of language and Number of persons who returned the mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother language tongue language tongue 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 13,168,484 13 Dhundhari 1,871,130 1 Assamese 12,778,735 14 Garhwali 2,267,314 Others 389,749 15 Gojri 762,332 16 Harauti 2,462,867 2 BENGALI 83,369,769 17 Haryanvi 7,997,192 1 Bengali 82,462,437 18 Hindi 257,919,635 2 Chakma 176,458 19 Jaunsari 114,733 3 Haijong/Hajong 63,188 20 Kangri 1,122,843 4 Rajbangsi 82,570 21 Khairari 11,937 Others 585,116 22 Khari Boli 47,730 23 Khortha/ Khotta 4,725,927 3 BODO 1,350,478 24 Kulvi 170,770 1 Bodo/Boro 1,330,775 25 Kumauni 2,003,783 Others 19,703 26 Kurmali Thar 425,920 27 Labani 22,162 4 DOGRI 2,282,589 28 Lamani/ Lambadi 2,707,562 -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

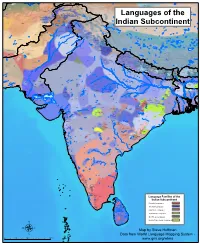

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

A Linguistic Insight Into Hindi and Haryanvi Language

International Journal of Innovations in TESOL and Applied Linguistics Vol. 5, Issue 3; 2020 ISSN 2454-6887 Published by ASLA, Amity University, Gurgaon, India © 2020 A Linguistic Insight into Hindi and Haryanvi Language Sangeeta Amity School of Liberal Arts Amity University Gurgaon, Haryana, India Received: Jan.10, 2020 Accepted: Jan.14, 2020 Online Published: Feb. 07, 2020 Abstract The prime objective of this study is to explore the similarities and differences between Hindi and Haryanvi language and words using lexicostatistical approach, word order, sentence structure, in doing so a representative sample of 130 basic words taken from Hindi (and English as a reference) followed by listing their equivalents in Haryanvi. The finding revealed 27 words with partial phonological similarity between Hindi and Haryanvi. Furthermore, the study also revealed that Haryanvi follows the same pattern of Hindi language, consonants, vowels, numerical and SOV. These two language belong to same family tree Devanagari and originated from Sanskrit. Introduction Hindi is the major language of India. Linguistically and as it is everyday spoken language, Hindi is virtually identical to Urdu, which is the national language of Pakistan. The two languages are often jointly referred to as Hindustani or Hindu-Urdu. The differences between them are found in formal situations and in writing. Whereas Urdu is written in a form of Arabic script, Hindi is written left to right in a script called Devanagari. Furthermore, much Urdu vocabulary derives from Persian / Arabic, while Sanskrit is the major supplier of Hindi words. Haryanvi language was the original language of Aryans who arrived in India 1500 BC.Haryanvi (हरयाणवी) is a dialect of the western Hindi group and it is written in Devanagari script. -

Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India

Chapter one: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India 1.1 Introduction: India also known as Bharat is the seventh largest country covering a land area of 32, 87,263 sq.km. It stretches 3,214 km. from North to South between the extreme latitudes and 2,933 km from East to West between the extreme longitudes. On this 2.4 % of earth‟s surface, lives 16% of world‟s population. With a population of 1,028,737,436 variations is there at every step of life. India is a land of bewildering diversity. India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the Figure 1.1: India in World Population south, the Arabian Sea on the west and the Bay of Bengal on the east. Many outsiders explored India via these routes. The whole of India is divided into twenty eight states and seven union territories. Each state has its own cultural and linguistic peculiarities and diversities. This diversity can be seen in every aspect of Indian life. Whether it is culture, language, script, religion, food, clothing etc. makes ones identity multi-dimensional. Ones identity lies in his language, his culture, caste, state, village etc. So one can say India is a multi-centered nation. Indian multilingualism is unique in itself. It has been rightly said, “Each part of India is a kind of replica of the bigger cultural space called India.” (Singh U. N, 2009). Also multilingualism in India is not considered a barrier but a boon. 17 Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India Languages act as bridges because it enables us to know about others. -

Bagri of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Haryana a Sociolinguistic Survey

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2011-048 ® Bagri of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Haryana A sociolinguistic survey Eldose K. Mathai Bagri of Rajasthan, Punjab, and Haryana A sociolinguistic survey Eldose K. Mathai SIL International ® 2011 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2011-048, December 2011 Copyright © 2011 Eldose K. Mathai and SIL International ® All rights reserved 2 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Geography 1.2 People 1.3 Language 1.4 Previous research 1.5 Purpose and goals 1.6 Limitations of the research 2 Dialect situation 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Procedures 2.3 Site selection 2.4 Results and analysis 3 Language use, attitudes, and vitality 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Questionnaire sample 3.3 Language use 3.4 Language attitudes 4 Bilingualism 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Tested levels of bilingualism in Hindi 4.2.1 Sentence Repetition Testing (SRT) procedures 4.2.2 Variables and sampling for SRT 4.2.3 Demographic profiles of the SRT sites 4.2.4 Results and analysis 4.3 Self–reported and observed bilingualism in Hindi 4.3.1 Questionnaire results and analysis 4.3.2 Observations 5 Summary of findings and recommendations 5.1 Findings 5.1.1 Dialect situation 5.1.2 Language use, attitudes, and vitality 5.1.3 Bilingualism 5.2 Recommendations 5.2.1 For language development 5.2.2 For literacy 5.2.3 For further research Appendix A. Map of Bagri survey region Appendix B. Wordlists References 3 Abstract The purpose of this sociolinguistic survey was to assess the need for mother tongue language development and literacy work in the Bagri language (ISO 639–3: bgq). -

Abstract of Speakers' Strength of Languages and Mother Tongues - 2011

STATEMENT-1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2011 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 121 languages and 270 mother tongues. The 22 languages specified in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India are given in Part A and languages other than those specified in the Eighth Schedule (numbering 99) are given in Part B. PART-A LANGUAGES SPECIFIED IN THE EIGHTH SCHEDULE (SCHEDULED LANGUAGES) Name of Language & mother tongue(s) Number of persons who Name of Language & mother tongue(s) Number of persons who grouped under each language returned the language (and grouped under each language returned the language (and the mother tongues the mother tongues grouped grouped under each) as under each) as their mother their mother tongue) tongue) 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 1,53,11,351 Gawari 19,062 Assamese 1,48,16,414 Gojri/Gujjari/Gujar 12,27,901 Others 4,94,937 Handuri 47,803 Hara/Harauti 29,44,356 2 BENGALI 9,72,37,669 Haryanvi 98,06,519 Bengali 9,61,77,835 Hindi 32,22,30,097 Chakma 2,28,281 Jaunpuri/Jaunsari 1,36,779 Haijong/Hajong 71,792 Kangri 11,17,342 Rajbangsi 4,75,861 Khari Boli 50,195 Others 2,83,900 Khortha/Khotta 80,38,735 Kulvi 1,96,295 3 BODO 14,82,929 Kumauni 20,81,057 Bodo 14,54,547 Kurmali Thar 3,11,175 Kachari 15,984 Lamani/Lambadi/Labani 32,76,548 Mech/Mechhia 11,546 Laria 89,876 Others 852 Lodhi 1,39,180 Magadhi/Magahi 1,27,06,825 4 DOGRI 25,96,767 -

![Mkwa0 Tks' Kh N{Kk Vkj]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4460/mkwa0-tks-kh-n-kk-vkj-4574460.webp)

Mkwa0 Tks' Kh N{Kk Vkj]

` Hindi S. No. Name & Address Subject Title of the project State Category SC/ST/OBC/ Gen. 1. MkWa0 jsuw nhf{kr, Hindi vk/kqfud fgUnh lkfgR; dh jktuhfrd i`"Bhkwfe Uttar Pradesh D. A. V. College, ¼ 1900&1960 ½ KANPUR. DIST.:Kanpur Nagar 208 001 2. Dr. Meera Rani Bal, Hindi Hindi Patrakarita Main Gandhi Chinton kai Uttar Pradesh Aligarh Muslim University, Naiya Kshitiz vision Aur Viimarsh Aligarh- 202 002 3. Dr. Devidas Yeshwant Ingale, Hindi fgUnh vkSj ejkBh ds ukVdkases fpaf=r N=ifr f'kokth Maharashtra ------- Ram Krishna Paramhansa egkjkt ds pfj= dh xq.kkRedrk dk rqyukResd v/;;u Mahavidyalaya, Osmanabad, Dist. Aurangabad- 413 501 4. Dr. Shobha Kaur, Hindi Jh nle xzaFk% ,sfrgkfld ,oa lkaLd`frd losZ{k.k Delhi Gen. Kirori Mal College, Delhi- 110 007 5. MkWa0 tks'kh n{kk vkj], Hindi The study of Hindi Travelogue with Gujarat -------- Late Minaben Kundalia Mahila reference to Global Cultural Perspective Arts and Commerce College, Rajkot, Dist. Rajkot-360 002 6. Dr. Ved Prakash Upadhyay, Hindi fgUnh& lkfgR; dh le`f} esa vkt+ex<+ tuin ds 'kh"k Uttar Pradesh Gen. S.D.J. P.G.College, lkfgR; & lz"Vkvksa dk vonku CHANDESHAR. DIST.:Azamgarh- 276 128 7. Dr. Palkar Amol Vitthal, Hindi Hindi aur marathi bal kahani sahity ke Maharashtra OBC Balbhim College of Arts Sc. & vividh Aayam Commerce, Beed- 431122 8. MkWa0 jes'k oekZ, Hindi tulapkj dzkafr esa tkxj.k izdk'ku fyfeVsM ¼ nSfud Uttar Pradesh Gen. Dayanand Anglo Vedic (PG) tkxj.k] iquuZok ½ dh Hkwfedk vkSj mldk lkekftd College, jktuhfrd o lkfgfR;d izHkko KANPUR. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Andras´ Kornai, Pushpak Bhattacharyya Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Algebra Indian Institute of Technology, Budapest Institute of Technology [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We describe the planned Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project, which aims at turning as many languages and dialects of the subcontinent into digitally viable languages as feasible. Keywords: digital vitality, language vitalization, Indian subcontinent In this position paper we describe the planned Indian Sub- gesting that efforts aimed at building language technology continent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project. In Sec- (see Section 4) are best concentrated on the less vital (but tion 1 we provide the rationale why such a project is called still vital or at the very least borderline) cases at the ex- for and some background on the language situation on the pense of the obviously moribund ones. To find this border- subcontinent. Sections 2-5 describe the main phases of the line we need to distinguish the heritage class of languages, planned project: Survey, Triage, Build, and Apply, offering typically understood only by priests and scholars, from the some preliminary estimates of the difficulties at each phase. still class, which is understood by native speakers from all walks of life. For heritage language like Sanskrit consider- 1. Background able digital resources already exist, both in terms of online The linguistic diversity of the Indian Subcontinent is available material (in translations as well as in the origi- remarkable, and in what follows we include here not nal) and in terms of lexicographical and grammatical re- just the Indo-Aryan family, but all other families like sources of which we single out the Koln¨ Sanskrit Lexicon Dravidian and individual languages spoken in the broad at http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier and the geographic area, ranging from Kannada and Telugu INRIA Sanskrit Heritage site at http://sanskrit.inria.fr. -

Haroti:!An!Enquiry!Into!Rajastani!Language!

Dialectologia!12,(2014),!53+65.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!17!July!2012.! Accepted!7!DecemBer!2012.! ! ! ! ! THE!STATUS!OF!HAROTI:!AN!ENQUIRY!INTO!RAJASTANI!LANGUAGE! Amitabh#Vikram#DWIVEDI# Shri#Mata#Vaishno#Devi#University,#India# [email protected]# # ! Abstract## The# present# paper# enquires# the# status# of# Haroti# lanGuage.# It# also# takes# into# consideration# the# problem#of#absence#and#paucity#of#data,#Grammatical#cateGories#that#are#closely#related#to#its#neiGhboring# Rajasthani#lanGuaGes,#and#not#commonly#examined#due#to#lack#of#data,#and#particularly#lanGuaGeKspecific# data#that#are#not#closely#related#to#other#languaGes;#and#it#is#also#an#effort#to#build#an#academic#consensus# on#its#more#distant#relations#that#are#not#yet#established., One# of# the# obvious# markers# of# a# reGional# lanGuaGe# today# is# accent.# NonKlinGuists# and# traditional# grammarians# generally# consider# the# varieties# of# Rajasthani# languages# as# mutually# intelligible# but# with# varyinG#under#the#accent#of#an#umbrella#term#‘Rajasthani’#for#the#various#eight#macro#and#micro#languages# spoken#in#this#reGion.# # Keywords# Haroti#lanGuaGe,#Rajasthani#languaGes,#reGional#lanGuaGe,#macro#and#micro#lanGuaGes# # # EL!ESTATUS!DEL!HAROTI:!UNA!INVESTIGACIÓN!EN!LA!LENGUA!RAJASTANI# Resumen# En#este#artículo#se#investiga#sobre#el#estado#de#la#lengua#Haroti.#Toma#también#en#consideración#el# problema#de#la#ausencia#y#la#escasez#de#datos,#las#cateGorías#Gramaticales#que#se#relacionan#estrechamente# con# las# lenGuas# rajastanis# vecinas,# y# que# -

Map by Steve Huffman, Data from World Language Mapping System V.3.2 (Ethnologue 15Th Ed.) New Zealand French Southern and Antarctic Lands

Greenland Svalbard Inuktitut, Greenlandic Inuktitut, Greenlandic Nganasan Nenets Dolgan Nenets Nganasan Yakut Nenets Nganasan Nenets Nganasan Nganasan Jan Mayen Dolgan Saami, North Saami, NorthSaami, North Nganasan Even Inuktitut, Greenlandic Nenets Saami, North Finnish, KvenSaami, North Saami, North Nenets Saami, North Saami, North Saami, North Saami, North Saami, North Saami, InariFinnish, Kven Even Saami, North Saami, North Nenets Nenets Nenets Nenets Saami, Skolt Chukot Saami, NorthSaami, North Saami, NorthSaami, North Nenets Even Yakut Saami, NorthSaami, Lule Saami, Kildin Nenets Nenets Saami, North Nenets Even Saami, Pite Finnish, Tornedalen Saami, North Saami, Ter Nenets Saami, PiteSaami, Pite Saami, Lule Nenets Nenets Finnish, Tornedalen Saami, Lule Saami, Ume Saami, Pite Selkup Selkup Icelandic Saami, Ume Saami, Pite Evenki Khanty Iceland Saami, Ume Karelian Komi-Zyrian Chukot Saami, SouthSaami, South Finland Mansi Saami, South Russia Finnish Selkup Saami, South Khanty Nenets Koryak Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Mansi Kerek Faroese Koryak Chukot Faroese Saami, South Mansi Koryak Kerek Ludian Selkup Saami, South Mansi Faroese Livvi Mansi Dalecarlian Veps Khanty Khanty Koryak Mansi Evenki Alutor Koryak Koryak Khanty Veps Koryak Alutor Swedish Swedish Swedish Selkup Koryak Vod Ingrian Komi-Permyak Alutor Finnish Koryak Estonian Selkup Estonian Gaelic, Scottish Estonia Evenki Gaelic, Scottish Liv Itelmen Udmurt Khakas Gaelic, Scottish Latvia Koryak Latvian Liv Russian Scots Denmark Mari, Eastern Itelmen Gaelic, Scottish Mari, Eastern