Sociolinguistic Survey of Selected Rajasthani Speech Varieties of Rajasthan, India Volume 1: Preliminary Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001 Presented Below Is an Alphabetical Abstract of Languages A

Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Census 2001 STATEMENT 1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2001 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 122 languages and 234 mother tongues. The 22 languages PART A - Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages) Name of language and Number of persons who returned the Name of language and Number of persons who returned the mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother language tongue language tongue 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 13,168,484 13 Dhundhari 1,871,130 1 Assamese 12,778,735 14 Garhwali 2,267,314 Others 389,749 15 Gojri 762,332 16 Harauti 2,462,867 2 BENGALI 83,369,769 17 Haryanvi 7,997,192 1 Bengali 82,462,437 18 Hindi 257,919,635 2 Chakma 176,458 19 Jaunsari 114,733 3 Haijong/Hajong 63,188 20 Kangri 1,122,843 4 Rajbangsi 82,570 21 Khairari 11,937 Others 585,116 22 Khari Boli 47,730 23 Khortha/ Khotta 4,725,927 3 BODO 1,350,478 24 Kulvi 170,770 1 Bodo/Boro 1,330,775 25 Kumauni 2,003,783 Others 19,703 26 Kurmali Thar 425,920 27 Labani 22,162 4 DOGRI 2,282,589 28 Lamani/ Lambadi 2,707,562 -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Agritourism Advantage Rajasthan

GLOBAL RAJASTHAN AGRITECH MEET 9-11 NOV 2016 JAIPUR AGRITOURISM ADVANTAGE RAJASTHAN Agritourism Advantage Rajasthan 1 Agritourism 2 Advantage Rajasthan TITLE Agritourism: Advantage Rajasthan YEAR November, 2016 AUTHORS Strategic Government Advisory (SGA), YES BANK Ltd Special &ĞĚĞƌĂƟŽŶŽĨ/ŶĚŝĂŶŚĂŵďĞƌƐŽĨŽŵŵĞƌĐĞΘ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌLJ;&//Ϳ Acknowledgement EŽƉĂƌƚŽĨƚŚŝƐƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶŵĂLJďĞƌĞƉƌŽĚƵĐĞĚŝŶĂŶLJĨŽƌŵďLJƉŚŽƚŽ͕ƉŚŽƚŽƉƌŝŶƚ͕ŵŝĐƌŽĮůŵŽƌĂŶLJŽƚŚĞƌ KWzZ/',d ŵĞĂŶƐǁŝƚŚŽƵƚƚŚĞǁƌŝƩĞŶƉĞƌŵŝƐƐŝŽŶŽĨz^E<>ƚĚ͘ dŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŝƐƚŚĞƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶŽĨz^E<>ŝŵŝƚĞĚ;͞z^E<͟ͿĂŶĚ&//ƐŽz^E<ĂŶĚ&//ŚĂǀĞĞĚŝƚŽƌŝĂů ĐŽŶƚƌŽůŽǀĞƌƚŚĞĐŽŶƚĞŶƚ͕ŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐŽƉŝŶŝŽŶƐ͕ĂĚǀŝĐĞ͕ƐƚĂƚĞŵĞŶƚƐ͕ƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐ͕ŽīĞƌƐĞƚĐ͘ƚŚĂƚŝƐƌĞƉƌĞƐĞŶƚĞĚŝŶ ƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘,ŽǁĞǀĞƌ͕z^E<͕&//ǁŝůůŶŽƚďĞůŝĂďůĞĨŽƌĂŶLJůŽƐƐŽƌĚĂŵĂŐĞĐĂƵƐĞĚďLJƚŚĞƌĞĂĚĞƌ͛ƐƌĞůŝĂŶĐĞ ŽŶŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶŽďƚĂŝŶĞĚƚŚƌŽƵŐŚƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘dŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŵĂLJĐŽŶƚĂŝŶƚŚŝƌĚƉĂƌƚLJĐŽŶƚĞŶƚƐĂŶĚƚŚŝƌĚͲƉĂƌƚLJ ƌĞƐŽƵƌĐĞƐ͘ z^ E< ĂŶĚͬŽƌ &// ƚĂŬĞ ŶŽ ƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJ ĨŽƌ ƚŚŝƌĚ ƉĂƌƚLJ ĐŽŶƚĞŶƚ͕ ĂĚǀĞƌƟƐĞŵĞŶƚƐ Žƌ ƚŚŝƌĚ ƉĂƌƚLJĂƉƉůŝĐĂƟŽŶƐƚŚĂƚĂƌĞƉƌŝŶƚĞĚŽŶŽƌƚŚƌŽƵŐŚƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͕ŶŽƌĚŽĞƐŝƚƚĂŬĞĂŶLJƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJĨŽƌƚŚĞŐŽŽĚƐ Žƌ ƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐ ƉƌŽǀŝĚĞĚ ďLJ ŝƚƐ ĂĚǀĞƌƟƐĞƌƐ Žƌ ĨŽƌ ĂŶLJ ĞƌƌŽƌ͕ŽŵŝƐƐŝŽŶ͕ ĚĞůĞƟŽŶ͕ ĚĞĨĞĐƚ͕ ƚŚĞŌ Žƌ ĚĞƐƚƌƵĐƟŽŶ Žƌ ƵŶĂƵƚŚŽƌŝnjĞĚĂĐĐĞƐƐƚŽ͕ŽƌĂůƚĞƌĂƟŽŶŽĨ͕ĂŶLJƵƐĞƌĐŽŵŵƵŶŝĐĂƟŽŶ͘&ƵƌƚŚĞƌ͕z^E<ĂŶĚ&//ĚŽŶŽƚĂƐƐƵŵĞ ĂŶLJƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJŽƌůŝĂďŝůŝƚLJĨŽƌĂŶLJůŽƐƐŽƌĚĂŵĂŐĞ͕ŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐƉĞƌƐŽŶĂůŝŶũƵƌLJŽƌĚĞĂƚŚ͕ƌĞƐƵůƟŶŐĨƌŽŵƵƐĞŽĨ ƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŽƌĨƌŽŵĂŶLJĐŽŶƚĞŶƚĨŽƌĐŽŵŵƵŶŝĐĂƟŽŶƐŽƌŵĂƚĞƌŝĂůƐĂǀĂŝůĂďůĞŽŶƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘dŚĞĐŽŶƚĞŶƚƐĂƌĞ ƉƌŽǀŝĚĞĚĨŽƌLJŽƵƌƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞŽŶůLJ͘ dŚĞƌĞĂĚĞƌͬďƵLJĞƌƵŶĚĞƌƐƚĂŶĚƐƚŚĂƚĞdžĐĞƉƚĨŽƌƚŚĞŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͕ƉƌŽĚƵĐƚƐĂŶĚƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐĐůĞĂƌůLJŝĚĞŶƟĮĞĚĂƐ ďĞŝŶŐƐƵƉƉůŝĞĚďLJz^E<ĂŶĚ&//ĚŽŶŽƚŽƉĞƌĂƚĞ͕ĐŽŶƚƌŽůŽƌĞŶĚŽƌƐĞĂŶLJŽƚŚĞƌŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͕ƉƌŽĚƵĐƚƐ͕Žƌ -

Spotlaw 2014

State of Rajasthan Vs Bhup Sing Criminal Appeal No. 377 of 1996 (Dr. A. S. Anand, K. T. Thomas JJ) 13.01.1997 JUDGMENT THOMAS, J. – 1. The respondent's wife (Mst. Chawli) was shot dead on 20-7-1985 while she was sleeping in her house. Respondent Bhup Singh was alleged to be the killer. The police, after investigation, upheld the allegation and challaned him. Though the Sessions Court convicted him of murder, the High Court of Rajasthan acquitted him. This appeal has been filed by special leave by the State of Rajasthan in challenge of the aforesaid acquittal. 2. The prosecution case is a very short story : Chawli was first married to the respondent's brother who died after a brief marital life. Thereafter, Chawli was given in marriage to the respondent, but the new alliance was marred by frequent skirmishes and bickerings between the spouses. Chawli was residing in the house of her parents. The estrangement between the couple reached a point of no return and the respondent wished to get rid of her. So he went to her house on the night of the occurrence and shot her with a pistol. When he tried to use the firearm again, Chawli's father who had heard the sound of the first shot rushed towards him and caught him but the killer escaped with the pistol. 3. Chawli told everybody present in the house that she was shot at by her husband Bhup Singh. She was taken to the hospital and the doctor who attended on her thought it necessary to inform a Judicial Magistrate that her dying declaration should be recorded. -

Mapping India's Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and Its

Mapping India’s Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and its Exclusion in the Indian Census Dr. Shivakumar Jolad1 and Aayush Agarwal2 1FLAME University, Lavale, Pune, India 2Centre for Social and Behavioural Change, Ashoka University, New Delhi, India Abstract In this article, we critique the process of linguistic data enumeration and classification by the Census of India. We map out inclusion and exclusion under Scheduled and non-Scheduled languages and their mother tongues and their representation in state bureaucracies, the judiciary, and education. We highlight that Census classification leads to delegitimization of ‘mother tongues’ that deserve the status of language and official recognition by the state. We argue that the blanket exclusion of languages and mother tongues based on numerical thresholds disregards the languages of about 18.7 million speakers in India. We compute and map the Linguistic Diversity Index of India at the national and state levels and show that the exclusion of mother tongues undermines the linguistic diversity of states. We show that the Hindi belt shows the maximum divergence in Language and Mother Tongue Diversity. We stress the need for India to officially acknowledge the linguistic diversity of states and make the Census classification and enumeration to reflect the true Linguistic diversity. Introduction India and the Indian subcontinent have long been known for their rich diversity in languages and cultures which had baffled travelers, invaders, and colonizers. Amir Khusru, Sufi poet and scholar of the 13th century, wrote about the diversity of languages in Northern India from Sindhi, Punjabi, and Gujarati to Telugu and Bengali (Grierson, 1903-27, vol. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Copyright by Kenneth Leland Price 2004

Copyright by Kenneth Leland Price 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Kenneth Leland Price certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discourse and Development: Language and Power in a Rural Rajasthani Meeting Committee: James Brow, Supervisor Shama Gamkhar Laura Lein Joel Sherzer Kathleen Stewart Discourse and Development: Language and Power in a Rural Rajasthani Meeting by Kenneth Leland Price, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research represents the fulfillment of a dream I have long held – to be able to sit with an elderly person in a village of rural India and to simply chat with him or her about whatever comes to mind. When I first came as a graduate student to the University of Texas at Austin, I hoped to learn how to ask good questions should I ever have that opportunity. First, I must thank my advisor throughout my journey and project, Dr. James Brow. He stood up for me and stood by me whenever I needed his support. He opened doors for my dreams to wander. He taught me the importance of learning how to ask better questions, and to keep questioning, everything I read, hear, and see. He directed me to the study of development in South Asia. Without Dr. Brow’s guidance, none of this would have been possible. The members of my dissertation committee contributed to my preparation for going “to the field” and my approach to the data after returning. -

Rajputana and Ajmer-Merwara, Part III, Vol-XXIV, Rajasthan

<CENSUS OF INDIA,- 1921. VOLUME XXIV RA-1PUTANA AND AJMER-MERWARA PART III I ADMINISTRATIVE VOLUME Agents for the Sale of Books PubI:shed by the Superintendent of Govemment Printing, India, Calcutta. IN EUROPE. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leioester Square, T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., To ,Adelphi Torrace, London, W.O. London, W.C. Kegan Paul, Trencb, Triibner & Co., 68·'74, Carter Lane, E.C., and 39, New Oxford Street, wndon, Wbeldon & Wesley, Ltd., 2,3 & 4, Anrthur Street, W.C. New Oxfurd Stree1i, London, W.C. 2. Bernard Qnaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond B. H. Blackwell, 50 & 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Street, London, W. Deighton, Bell & Co., Ltd., Cambridge. P. S. King & Sons, 2 & 4, Great Smith Street, West. , lninster, Londoo, S.W. Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. E. Pon80nby, Ltd., 116, Grafton Stn.ct, Dublin. H. S. King & Co., 65, CornhilI, E.C., and 9, Pall Mall, London, W. Ernest Leroux, 28, Rue Bonap~rte, Paris. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S. W. MartIDus Nijholf, The Hague, Holland. Luzao & Co., 46, Great Russoll Stree·t, London, W.C· Friedlander and Sohn, Berlin. W. Tbaoker &: Co., 2, Creed Lane, London, E.C. Otto L.arrassowitz, Leipzig. II INDIA ABD CEYLOIl. thacker. Spink & CI1., Calcutta. and Simla.. Proprietor, New Kitabkhana, Poona. NewIll&n & Co., Calcutta. The Standard Bookstall, Karachi. &. Cambr~y & Co., Calcutta. Mangaldas Harkisaudas, Surat. 8. K. Lahiri &; Co., Calcutta. Karsandas Narandas & Sons, Surat. B. Banerjee &; Co., Calcutta. A. H. Wheeler &; Co., Allahabad. Calcutta and Bombay. The India.n School Supply DepOt, 309, nI:JW 13M.a.r N. -

Przeglad Orient 2-19.Indd

ALEKSANDRA TUREK DOI 10.33896/POrient.2019.2.5 Uniwersytet Warszawski RADŹASTHANI – POCZĄTKI JĘZYKA I LITERATURY ABSTRACT: The paper presents a general introduction of Rajasthani – the language used in North-Western India – the development of the language and the beginnings of Rajasthani literature. It also draws attention to the complexity of linguistic nomenclature used for Rajasthani and to its relation with other North Indian languages, with a special regard to Hindi. The rise of literary tradition in the vernacular of North-Western India and its connection with the history of Hindi literature is analysed. Rajasthani is considered to be the first vernacular of North India in which literature has evolved, and hence predates the oldest works from the region known as Hindi belt by at least two hundred years. Rajasthani and Gujarati used to have one linguistic form, which only split into two languages after the 15th century whereby Rajasthani adopted its modern form, still used today, and Gujarati developed independently. The claims of some scholars that the initial literary period of North-Western India – i.e. until the 15th century – be included in the history of Hindi literature are also presented in the paper. KEYWORDS: Rajasthan, Rajasthani language, Rajasthani literature, Hindi, Adi Kal Radźasthani (rājasthānī) to ogólny termin na określenie różnorodnych form języ- kowych, mających własne liczne odmiany dialektalne, używanych na obszarze Radźa- sthanu (Rājasthān), czyli tej części północno-zachodnich Indii, która mieści się w gra- nicach współczesnego stanu o tej samej nazwie. Warto jednak pamiętać, że podobnie jak większość nazw poszczególnych języków regionalnych Indii Północnych, także ten termin wprowadzono dość późno, na przełomie XIX i XX w. -

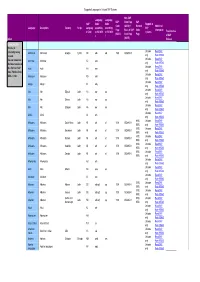

Supported Languages in Unicode SAP Systems Index Language

Supported Languages in Unicode SAP Systems Non-SAP Language Language SAP Code Page SAP SAP Code Code Support in Code (ASCII) = Blended Additional Language Description Country Script Languag according according SAP Page Basis of SAP Code Information e Code to ISO 639- to ISO 639- systems Translated as (ASCII) Code Page Page 2 1 of SAP Index (ASCII) Release Download Info: AThis list is Unicode Read SAP constantly being Abkhazian Abkhazian Georgia Cyrillic AB abk ab 1500 ISO8859-5 revised. only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP You can download Achinese Achinese AC ace the latest version of only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP this file from SAP Acoli Acoli AH ach Note 73606 or from only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP SDN -> /i18n Adangme Adangme AD ada only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Adygei Adygei A1 ady only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Djibouti Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Eritrea Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Ethiopia Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afrihili Afrihili AI afh only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans South Africa Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Botswana Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Malawi Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Namibia Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Zambia -

Final Electoral Roll / Voter List (Alphabetical), Election - 2018

THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL / VOTER LIST (ALPHABETICAL), ELECTION - 2018 [As per order dt. 14.12.2017 as well as orders dt.23.08.2017 & 24.11.2017 Passed by Hon'ble Supreme Court of India in Transfer case (Civil) No. 126/2015 Ajayinder Sangwan & Ors. V/s Bar Council of Delhi and BCI Rules.] AT SIROHI IN SIROHI JUDGESHIP LOCATION OF POLLING STATION :- BAR ROOM, JUDICIAL COURTS, SIROHI DATE 01/01/2018 Page 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Electoral Name as on the Roll Electoral Name as on the Roll Number Number ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ ' A ' 3760 SH.AIDAN PUROHIT 57131 SH.AKSHAY SHARMA 81138 SH.ALTAMASH SHAIKH 78813 SMT.AMITA MEENA 23850 SH.ANAND DEV SUMAN 25666 SH.ARJUN KUMAR RAWAL 81279 SH.ARVIND SINGH 70087 SH.ASHOK KUMAR 25596 SH.ASHOK KUMAR PUROHIT 53709 SH.ASHU RAM KALBI 11856 SH.ASHWIN MARDIA ' B ' 81083 SH.BALWANT KUMAR MEGHWAL 6592 SH.BASANT KUMAR BHATI 26011 SH.BHAGWAT SINGH DEORA 34679 SH.BHANWAR SINGH DEORA 35577 SH.BHARAT KHANDELWAL 80034 SH.BHARAT KUMAR SEN 12869 SH.BHAWANI SINGH DEORA 60347 SH.BHERUPAL SINGH 12311 SH.BHIKH SINGH ARHA ' C ' 18417 SH.CHAMPAT LAL PARMAR 41619 SH.CHANDAN SINGH DABI 69381 SH.CHANDRA PRAKASH SINGH KUMPAWAT 70977 KUM.CHARCHA SHARMA 40116 KUM.CHETANA ' D ' 11363 SH.DALIP SINGH DEORA 38565 SH.DALPAT