The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Qt7vk4k1r0 Nosplash 9Eebe15

Fiction Beyond Secularism 8flashpoints The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Founding Editor; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Nouri Gana (Comparative Literature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) 1. On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant, Dina Al-Kassim 2. Moses and Multiculturalism, Barbara Johnson, with a foreword by Barbara Rietveld 3. The Cosmic Time of Empire: Modern Britain and World Literature, Adam Barrows 4. Poetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric Modernity, Michelle Clayton 5. Disarming Words: Empire and the Seductions of Translation in Egypt, Shaden M. -

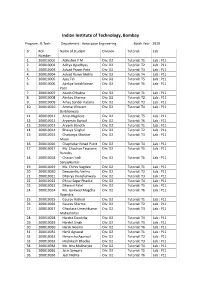

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Sindh Police Shaheed List

List of Shuhada of Sindh Police since 1942 to 2014 Date of Ser # Rank No. NAME Father Name Surname DSTT: Shahadat 1 IP K/1296 Ghazanfar Kazmi Syed Sarwar Ali Syed Kazmi South, Karachi 13.08.2014 2 PC 11049 Muhammad Siddiq Zer Muhammad Court Police 18.12.2013 3 PC 188 PC/188 Muhammad Khalid Muhammad Siddique Arain SBA, District 07.06.2014 4 HC 20296 HC/20296 Zulfqar Ali Unar s/o M Sachal Muhammad Sachal Unar Crime Br. Sukkur 29.07.2014 5 HC 17989 HC/17989 Haji Wakeel Ali Khair Muhammad West Karachi 17.08.2014 6 HC 13848 HC/ 13848 Tahir Mehmood Muhammad Aslam SRP-1, Karachi 19.08.2014 7 HC 19323 HC/19323 Azhar Abbas Muhammad Shafi Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 8 PC 19386 PC/19386 Muhammad Azam Mir Muhammad Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 9 PC 24318 PC/24318 Junaid Akbar Javed Akbar West Karachi 27.08.2014 10 PC 18442 PC/18442 Lutufullah Charann Muhammad Waris Charann Malir, Karachi 29.08.2014 11 ASI ASI Jamil Ahmed Babar Haji Ali Nawaz Babar Jamshoro 03.09.2014 12 HC 9636 HC/9636 Yousuf Khan Khushhal Khan Security-II 04.09.2014 13 SI K-5431 SI (K-5431) Ghulam Sarwar Gulsher Ali Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 14 PC 14491 PC/14491 Aijaz Ahmed Niaz Ahmed Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 15 HC 41 HC/41 Bashir Qureshi Allah Rakhio Qureshi Jamshoro 19.09.2014 16 PC 247 PC/247 Ameer Ali Junejo Roshan Ali Junejo Larkana 22.09.2014 17 PC 16150 PC/16150 Muhammad Tahir Farooq Muhammad Alam Central, Karachi 23.09.2014 18 DPC 18908 DPC/18908 Waqar Hashmi Shafiq Hashmi Hashmi Muhafiz Force, Karachi 16.10.2014 19 ASI K-2272 ASI/ K-2272 Qalandar Bux Malhan Khan Chandio -

Rajasthan List.Pdf

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan Date Of Area Of S.No Name Category Father's Name Address Enrol. No. & Date App'n Practice Village Lodipura Post Kamal Kumar Sawai Madho Lal R/2917/2003 1 Obc 01.05.18 Khatupura ,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.28.12.03 Madhopur,Rajasthan Village Sukhwas Post Allapur Chhotu Lal Sawai Laddu Lal R/1600/2004 2 Obc 01.05.18 Tehsil Khandar,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.02.10.04 Madhopur,Rajasthan Sindhu Farm Villahe Bilwadi Ram Karan R/910/2007 3 Obc 01.05.18 Shahpura Suraj Mal Tehsil Sindhu Dt.22.04.07 Viratnagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Opposite 5-Kha H.B.C. Sanjay Nagar Bhatta Basti R/1404/2004 4 Abdul Kayam Gen 02.05.18 Jaipur Bafati Khan Shastri Dt.02.10.04 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Jajoria Bhawan Village- Parveen Kumar Ram Gopal Keshopura Post- Vaishali R/857/2008 5 Sc 04.05.18 Jaipur Jajoria Jajoria Nagar Ajmer Dt.28.06.08 Road,Jaipur,Rajasthan Kailash Vakil Colony Court Road Devendra R/3850/2007 6 Obc 08.05.18 Mandalgarh Chandra Mandalgarh,Bhilwara,Rajast Kumar Tamboli Dt.16.12.07 Tamboli han Bhagwan Sahya Ward No 17 Viratnagar R/153/1996 7 Mamraj Saini Obc 03.05.18 Viratnagar Saini ,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.09.03.96 156 Luharo Ka Mohalla R/100/1997 8 Anwar Ahmed Gen 04.05.18 Jaipur Bashir Ahmed Sambhar Dt.31.01.97 Lake,Jaipur,Rajasthan B-1048-49 Sanjay Nagar Mohammad Near 17 No Bus Stand Bhatta R/1812/2005 9 Obc 04.05.18 Jaipur Abrar Hussain Salim Basti Shastri Dt.01.10.05 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Vill Bislan Post Suratpura R/651/2008 10 Vijay Singh Obc 04.05.18 Rajgarh Dayanand Teh Dt.05.04.08 Rajgarh,Churu,Rajasthan Late Devki Plot No-411 Tara Nagar-A R/41/2002 11 Rajesh Sharma Gen 05.05.18 Jaipur Nandan Jhotwara,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.12.01.02 Sharma Opp Bus Stand Near Hanuman Ji Temple Ramanand Hanumangar Rameshwar Lal R/29/2002 12 Gen 05.05.18 Hanumangarh Sharma h Sharma Dt.17.01.02 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an Ward No 23 New Abadi Street No 17 Fatehgarh Hanumangar Gangabishan R/3511/2010 13 Om Prakash Obc 07.05.18 Moad Hanumangarh h Bishnoi Dt.14.08.10 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an P.No. -

CRAFT and TRADE in the 18Th CENTURY RAJASTHAN

CRAFT AND TRADE IN THE 18th CENTURY RAJASTHAN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)ilos;opl)p IN )/er HISTORY ! SO I A. // XATHAR HUSSAIN -- .A Under the Supervision of Prof. B. L. Bhadani Chairman & Coordinator CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ^Ci>Musu m ABSTRACT The study on the 18* century has been attracting the attention of the historians such as Richard Bamett, C.A. Bayly, Muzaffar Alam, Andre Wink, Chetan Singh and others. Two subsequent works on the eastern Rajasthan by S.P. Gupta and Dilbagh Singh and on the northern Rajasthan by G.S.L. Devra have added new dimensions to the whole issue of existing debate on the 18' century, a period of transition in the history of India. Therefore, the importance of the studies on Rajasthan assumes significance which contains a treasure house of archival records, hitherto largely unexplored. My work is consisted of eight chapters with an introduction and conclusion. The first chapter deals with the study of geographical and historical profile of the Rajasthan. The geographical factor such as types of soils, hills, river and vegetation always nourishes the economy of the region. The physical location of Rajasthan had influenced its history to a greater extent. The region bears the physical diversity and we can divide it into two parts namely in the fertile south eastern zone and the thar arid zone. It was bounded by the Mughal subas (provinces) like Multan, Sindh, Delhi, Agra, Gujarat and Malwa. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Monograph Series Chhimbe, Part-VB(Iv)

ETHNOGRAPffiC STUDY No. 19 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I . MONOGRAPH SERIES Part V-B(iv) CHIDMBE A Scheduled Caste in Himachal Pradesh InvesfigatwlI R. P. NAULA and draft M: Sc. Supervision, N. G. NAG Guidance and Editing Dr. B. K. ROY Consultant BURMAN, M. Sc. j D. Phil. omCE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS PAGE Foreword (vii) Preface ix-xi 1. Name, Identity and Origin 1 2. Distribution and population trend (i) Sex ratio 4 (ii) Rural-urban distribution " 4 (iii) Population trend 4 3. Physical characteristics :' '. 5 4. Famiiy and inheritance of property 5 5. Clan and other analogous divisions 8 6. Settlement and dwellings 8 7, Dress, ornaments and tattooing .' 9 8, Food and drink 11 9, Hygienic habits, diseases and their treatment 12 10, Language, literacy and education 12 11. Occupation and economic life (i) Working force and industrial classification of workers 15 eii) O~cupational mobility 16 (iii) Occupational details -. 16 (iv) Agriculture ' 16 (v) Washing and dry cleaning 18 (vi) Tailoring 19 / (vii) Hand printing and textile dyeing 19 12. Life cycle (i) Birth 20 (ii) The first eating of grains 21 (iii) Tonsure 21 (iv) Marriage and sex life 22 (v) Modes of acquiring a mate 22 (vi) Consummation of marriage 25 (vii) Widow re-marriage 2S (viii) Divorce and separation 26 (ix) Pre-marital and extra-marital relations .-- . v 26 (x) Death rites 27 (iv) 13. Religion PAGB (i) Omens and superstitions 31 .~ (ii) Concept of soul o' .3'! 14. Leisure and recreation 31 15. -

Sikhism Reinterpreted: the Creation of Sikh Identity

Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-16-2014 Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Brittany Fay Puller Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the Asian History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Puller, Brittany Fay, "Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sikhism Reinterpreted: The rC eation of Sikh Identity Abstract The iS kh identity has been misinterpreted and redefined amidst the contemporary political inclinations of elitist Sikh organizations and the British census, which caused the revival and alteration of Sikh history. This thesis serves as a historical timeline of Punjab’s religious transitions, first identifying Sikhism’s emergence and pluralism among Bhakti Hinduism and Chishti Sufism, then analyzing the effects of Sikhism’s conduct codes in favor of militancy following the human Guruship’s termination, and finally recognizing the identity-driven politics of colonialism that led to the partition of Punjabi land and identity in 1947. Contemporary practices of ritualism within Hinduism, Chishti Sufism, and Sikhism were also explored through research at the Golden Temple, Gurudwara Tapiana Sahib Bhagat Namdevji, and Haider Shaikh dargah, which were found to share identical features of Punjabi religious worship tradition that dated back to their origins. -

Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan

PRG 335 (N) 1,000 ETHNOGRAPHIC ATLAS OF RAJASTHAN (WITH REFERENCE TO SCHEDULED CASTES & SCHEDULED TRIBES) U.B. MATHUR OF THE RAJASTHAN STATISTICAL SERVICE Deputy Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan. GANDHI CENTENARY YEAR 1969 To the memory of the Man Who spoke the following Words This work is respectfully Dedicated • • • • "1 CANNOT CONCEIVE ANY HIGHER WAY OF WORSHIPPING GOD THAN BY WORKING FOR THE POOR AND THE DEPRESSED •••• UNTOUCHABILITY IS REPUGNANT TO REASON AND TO THE INSTINCT OF MERCY, PITY AND lOVE. THERE CAN BE NO ROOM IN INDIA OF MY DREAMS FOR THE CURSE OF UNTOUCHABILITy .•.. WE MUST GLADLY GIVE UP CUSTOM THAT IS AGA.INST JUSTICE, REASON AND RELIGION OF HEART. A CHRONIC AND LONG STANDING SOCIAL EVIL CANNOT BE SWEPT AWAY AT A STROKE: IT ALWAYS REQUIRES PATIENCE AND PERSEVERANCE." INTRODUCTION THE CENSUS Organisation of Rajasthan has brought out this Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan with reference to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. This work has been taken up by Dr. U.B. Mathur, Deputy Census Superin tendent of Rajasthan. For the first time, basic information relating to this backward section of our society has been presented in a very comprehensive form. Short and compact notes on each individual caste and tribe, appropriately illustrated by maps and pictograms, supported by statistical information have added to the utility of the publication. One can have, at a glance. almost a complete picture of the present conditions of these backward communities. The publication has a special significance in the Gandhi Centenary Year. The publication will certainly be of immense value for all official and Don official agencies engaged in the important task of uplift of the depressed classes. -

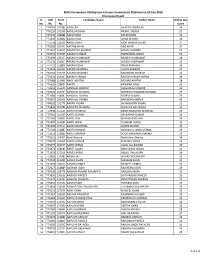

Sl. No. Roll No. Form No. Candidate Name Father Name Online Test

RUHS Paramedical UG/Diploma Entrance Examination 2018 held on 22-July-2018 Provisional Result Sl. Roll Form Candidate Name Father Name Online test No. No. No. Score 1 774709 157580 AADIL ALI AKHTAR JAWED ALI 24 2 776110 152356 AADIL HUSSAIN MOHD. SADDIK 23 3 775335 158688 AADIL KHAN ZAFAR KHAN 30 4 773345 153862 AADIL KHAN ILIYAS AHMED 34 5 775548 158239 AADIL SHEKH MOH ANWAR SHEKH 27 6 770300 150497 AAFTAB KHAN AZIZ KHAN 27 7 771637 154595 AAKANSHA SHARMA KAMAL SHARMA 27 8 774515 157095 AAKASH KUMAR MAHENDRA SINGH 53 9 775699 150357 AAKASH KUMAWAT MUKESH KUMAWAT 28 10 775130 156807 AAKASH KUMAWAT SURESH KUMAWAT 31 11 774711 152808 AAKASH OJHA PREM PRAKASH 33 12 774032 155356 AAKASH SHARMA LALITA SHARMA 19 13 774263 157776 AAKASH SHARMA RAMDHAN SHARMA 20 14 775634 156007 AAKASH VERMA RAJESH KUMAR VERMA 28 15 773588 151461 AAKIF AKHTAR ARSHAD AKHTAR 28 16 776626 158824 AAKRTI KANWAR SINGH 26 17 770659 155640 AANCHAL DINDOR MAGANLAL DINDOR 22 18 775121 154734 AANCHAL SHARMA MAHESH CHANDRA SHARMA 24 19 772086 158087 AANCHAL SUMAN SURESH SUMAN 25 20 775097 150908 AANCHAL VERMA RAJENDRA VERMA 49 21 774632 152376 AARAV YADAV JAI NARAYAN YADAV 23 22 771846 157780 AAROHEE SHARMA Kishan lal loknathaka 30 23 772930 155169 AARTI DHABHAI BADRI NARAYAN DHABHAI 29 24 770741 151563 AARTI GURJAR DEVKARAN GURJAR 24 25 773160 156830 AARTI JAIN BHAGCHAND JAIN 34 26 773407 154289 AARTI JAIPAL TEJARAM JAIPAL 32 27 771420 157114 AARTI MEGHWAL ASHOK KUMAR 31 28 772749 152887 AARTI PANWAR SUBHASH CHAND VERMA 19 29 775073 153889 AARTI SHARMA ROOP NARAYAN SHARMA -

Prospectus Media Courses 2012-13

Code No. Mass-12 Prospectus Media Courses 2012-13 Logo INSTITUTE OF MASS COMMUNICATION & MEDIA TECHNOLOGY KURUKSHETRA UNIVERSITY, KURUKSHETRA-136119 (Established by the State Legislature Act XII of 1956) ("A"Grade, NAAC Accredited) 1 Media Courses Under graduate courses: 1. B.A. (Mass Communication): 3 Years 2. B. Tech. (Printing, Graphics and Packaging): 4 Years Five year integrated courses: 3. Five year Integrated course in Multimedia-B.Sc. (Multimedia): 3 Years and M.Sc. (Multi media): 2 Years 4. Five year Integrated course in Graphhics & Animation-B.Sc.: 3 Years and M.Sc. (Graphics & Animation) M.Sc. G&A: 2 Years Post Graduate Courses: 5. M.Sc. (Mass Communication) : 2 Years 6. M.Sc. (Electronic Media): 2 Years 7. M.A. (Journalism & Mass Communication) : 2 Years Research courses: 8. M.Phil. (Journalism and Mass Communicaion) : 1 Year 9. Ph.D. (Journalism and Mass Communication) 2 STATUTORY OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY Hon'ble Chancellor Shri Jagannath Pahadia Governor, Haryana Vice-Chancellor Lt Gen (Dr) D D S Sandhu, 238039 PVSM, ADC (Retd.), D.Litt. (Mgt.), Ph.D., M.Phil., MBA, M.Sc., MMM, MDBA Registrar Dr Surinder Deswal 238026 M.Tech., Ph.D. Dean, Academic Affairs Prof Girish Chopra 238045 M.Sc., Ph. D. Dean, Students’ Welfare Prof Anil Vashisth 238096 M.Sc., Ph. D. Dean of Colleges Prof DD Arora 238347 M.Com., Ph. D., LLB. Proctor Prof C.R. Dharolia 239742 M.A. Ph. D. Chief Warden (Girls Hostels) Prof Ashu Shokeen 238711 M.A., Ph.D Chief Warden (Boys Hostels) Dr Sat Dev 238711 M.A., Ph. D.